Cooperative Verbal Communication

Eager to connect with your teenage son, you ask him how his day was when he arrives home from school. But you get only a grunted “Fine” in return, as he quickly disappears into his room to play video games. You invite your romantic partner over for dinner, excited to demonstrate a new recipe. But when you query your partner’s opinion of the dish, the response is, “It’s interesting.” You text your best friend, asking for her feedback on an in-class presentation you gave earlier that day. She responds, “You talked way too fast!”

Although these examples seem widely disparate, they share an underlying commonality: people failing to verbally communicate in a fully cooperative fashion. To understand how these messages are uncooperative, consider their cooperative counterparts. Your son tells you, “It was all right—I didn’t do as well on my chem test as I wanted, but I got an A on my history report.” Your partner says, “It’s good, but I think it’d be even better with a little more salt.” Your friend’s text message reads, “It went well, but I thought it could have been presented a little slower.”

When you use cooperative verbal communication, you produce messages that have three characteristics. First, you speak in ways that others can easily understand, using language that is informative, honest, relevant, and clear. Second, you take active ownership for what you’re saying by using “I” language. Third, you make others feel included rather than excluded—for example, through the use of “we.”

205

UNDERSTANDABLE MESSAGES

In his exploration of language and meaning, philosopher Paul Grice noted that cooperative interactions rest on our ability to tailor our verbal communication so that others can understand us. To produce understandable messages, we have to abide by the Cooperative Principle: making our conversational contributions as informative, honest, relevant, and clear as is required, given the purposes of the encounters in which we’re involved (Grice, 1989).

self-reflection

Recall a situation in which you possessed important information but knew that disclosing it would be personally or relationally problematic. What did you do? How did your decision impact your relationship? Was your choice ethical? Based on your experience, is it always cooperative to disclose important information?

Being aware of situational characteristics is critical to applying the Cooperative Principle. For example, while we’re ethically bound to share important information with others, this doesn’t mean we always should. Suppose a friend discloses a confidential secret to you and your sibling later asks you to reveal it. In this case, it would be unethical to share this information without your friend’s permission.

Being Informative According to Grice (1989), being informative during interpersonal encounters means two things. First, you should present all of the information that is relevant and appropriate to share, given the situation. When a coworker passes you in the hallway and greets you with a quick “How’s it going?” the situation requires that you provide little information in return—“Great! How are you?” The same question asked by a concerned friend during a personal crisis creates very different demands; your friend likely wants a detailed account of your thoughts and feelings.

Second, you want to avoid being too informative—that is, disclosing information that isn’t appropriate or important in a particular situation. A detailed description of your personal woes (“I haven’t been sleeping well lately, and my cat is sick . . . ”) in response to your colleague’s quick “How’s it going?” query would likely be perceived as inappropriate and even strange.

206

The responsibility to be informative overlaps with the responsibility to be ethical. To be a cooperative verbal communicator, you must share information with others that has important personal and relational implications for them. To illustrate, if you discover that your friend’s spouse is having an affair, you’re ethically obligated to disclose this information if your friend asks you about it.

Being Honest Honesty is the single most important characteristic of cooperative verbal communication because other people count on the fact that the information you share with them is truthful (Grice, 1989). Honesty means not sharing information that you’re uncertain about and not disclosing information that you know is false. When you are dishonest in your verbal communication, you violate standards for ethical behavior, and you lead others to believe false things (Jacobs, Dawson, & Brashers, 1996). For example, if you assure your romantic partner that your feelings haven’t changed when in fact they have, you give your partner false hope about your future together. You also lay the groundwork for your partner to make continued investments in a relationship that you already know is doomed.

Being Relevant Relevance means making your conversational contributions responsive to what others have said. When people ask you questions, you provide answers. When they make requests, you grant or reject their requests. When certain topics arise in the conversation, you tie your contributions to that topic. During conversations, you stick with relevant topics and avoid those that aren’t. Dodging questions or abruptly changing topics is uncooperative, and in some instances, others may see it as an attempt at deception, especially if you change topics to avoid discussing something you want to keep hidden (McCornack, 2008).

Being Clear Using clear language means presenting information in a straightforward fashion rather than framing it in obscure or ambiguous terms. For example, telling a partner that you like a recipe but that it needs more salt is easier to understand than veiling your meaning by vaguely saying, “It’s interesting.” But note that using clear language doesn’t mean being brutally frank or dumping offensive and hurtful information on others. Competent interpersonal communicators always consider others’ feelings when designing their messages. When information is important and relevant to disclose, choose your words carefully to be both respectful and clear, so that others won’t misconstrue your intended meaning.

self-reflection

Recall an online encounter in which you thought you understood someone’s e-mail, text message, or post, then later found out you were wrong. How did you discover that your impression was mistaken? What could you have done differently to avoid the misunderstanding?

Dealing with Misunderstanding Of course, just because you use informative, honest, relevant, and clear language doesn’t guarantee that you will be understood by others. When one person misperceives another’s verbally expressed thoughts, feelings, or beliefs, misunderstanding occurs. Misunderstanding most commonly results from a failure to actively listen. Recall, for example, our discussion of action-oriented listeners in Chapter 6. Action-oriented listeners often become impatient with others while listening and frequently jump ahead to finish other people’s (presumed) points (Watson, Barker, & Weaver, 1995). This listening style can lead them to misunderstand others’ messages. To overcome this source of misunderstanding, practice the active listening skills described in Chapter 6.

207

Misunderstanding occurs frequently online, owing to the lack of nonverbal cues to help clarify one another’s meaning. One study found that 27.2 percent of respondents agreed that e-mail is likely to result in miscommunication of intent, and 53.6 percent agreed that it is relatively easy to misinterpret an e-mail message (Rainey, 2000). The tendency to misunderstand communication online is so prevalent that scholars suggest the following practices: If a particular message absolutely must be error-free or if its content is controversial, don’t use e-mail or text messaging to communicate it. Whenever possible, conduct high-stakes encounters, such as important attempts at persuasion, face-to-face. Finally, never use e-mails, posts, or text messages for sensitive actions, such as professional reprimands or dismissals, or relationship breakups (Rainey, 2000).

USING “I” LANGUAGE

It’s the biggest intramural basketball game of the year, and your team is down by a point, with five seconds left, when your teammate is fouled. Stepping to the line for two free throws and a chance to win the game, she misses both, and your team loses. As you leave the court, you angrily snap at her, “You really let us down!”

The second key to cooperative verbal communication is taking ownership of the things you say to others, especially in situations in which you’re expressing negative feelings or criticism. You can do this by avoiding “you” language, phrases that place the focus of attention and blame on other people, such as “You let us down.” Instead, rearrange your statements so that you use “I” language, phrases that emphasize ownership of your feelings, opinions, and beliefs (see Table 7.2). The difference between “I” and “you” may strike you as minor, but it actually has powerful effects: “I” language is less likely than “you” language to trigger defensiveness on the part of your listeners (Kubany, Richard, Bauer, & Muraoka, 1992). “I” language creates a clearer impression on listeners that you’re responsible for what you’re saying and that you’re expressing your own perceptions rather than stating unquestionable truths.

208

| “You” Language | “I” Language |

|---|---|

| You make me so angry! | I’m feeling so angry! |

| You totally messed things up. | I feel like things are totally messed up. |

| You need to do a better job. | I think this job needs to be done better. |

| You really hurt my feelings. | I’m feeling really hurt. |

| You never pay any attention to me. | I feel like I never get any attention. |

USING “WE” LANGUAGE

It’s Thursday night, and you’re standing in line waiting to get into a club. In front of you are two couples, and you can’t help but overhear their conversations. As you listen, you notice an interesting difference in their verbal communication. One couple expresses everything in terms of “I” and “you”: “What do you want to do later tonight?” “I don’t know, but I’m hungry, so I’ll probably get something to eat. Do you want to come?” The other couple consistently uses “we”: “What should we do later?” “Why don’t we get something to eat?”

What effect does this simple difference in pronoun usage—“we” rather than “I” or “you”—have on your impressions of the two couples? If you perceive the couple using “we” as being closer than the couple using “I” and “you,” you would be right. “We” is a common way people signal their closeness (Dreyer, Dreyer, & Davis, 1987). Couples who use “we” language—wordings that emphasize inclusion—tend to be more satisfied with their relationships than those who routinely rely on “I” and “you” messages (Honeycutt, 1999).

An important part of cooperative verbal communication is using “we” language to express your connection to others. In a sense, “we” language is the inverse of “I” language. We use “I” language when we want to show others that our feelings, thoughts, and opinions are separate from theirs and that we take sole responsibility for our feelings, thoughts, and opinions. But “we” language helps us bolster feelings of connection and similarity, not only with romantic partners but also with anyone to whom we want to signal a collaborative relationship. When I went through my training to become a certified yoga instructor, part of the instruction was to replace the use of “you” with “we” and “let’s” during in-class verbal cueing of moves. Rather than saying, “You should lunge forward with your left leg” or “I want you to step forward left,” we were taught to say, “Let’s step forward with our left legs.” After I implemented “we” language in my yoga classes, my students repeatedly commented on how they liked the “more personal” and “inclusive” nature of my verbal cueing.

GENDER AND COOPERATIVE VERBAL COMMUNICATION

skillspractice

Cooperative Language Online

Using cooperative language during an important online interaction

Identify an important online encounter.

Create a rough draft of the message you wish to send.

Check that the language you’ve used is fully informative, honest, relevant, and clear.

Use “I” language for all comments that are negative or critical.

Use “we” language throughout the message, where appropriate.

Send the message.

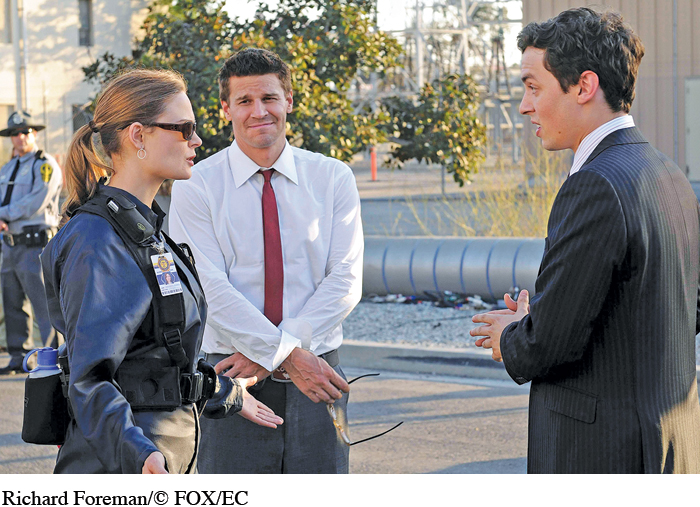

Powerful stereotypes exist regarding what men and women value in verbal communication. These stereotypes suggest that men appreciate informative, honest, relevant, and clear language more than women do. In Western cultures, many people believe that men communicate in a clear and straightforward fashion and that women are more indirect and wordy (Tannen, 1990b). These stereotypes are reinforced powerfully through television, in programs in which female characters often use more polite language than men (“I’m sorry to bother you but . . . ”), more uncertain phrases (“I suppose . . . ”), and more flowery adjectives (“that’s silly,” “oh, how beautiful”), and male characters fill their language with action verbs (“let’s get a move on!”) (Mulac, Bradac, & Mann, 1985).

209

But research suggests that when it comes to language, men and women are more similar than different. For example, data from 165 studies involving nearly a million and a half subjects found that women do not use more vague and wordy verbal communication than men do (Canary & Hause, 1993). The primary determinant of whether people’s language is clear and concise or vague and wordy is not gender but whether the encounter is competitive or collaborative (Fisher, 1983). Both women and men use clear and concise language in competitive interpersonal encounters, such as when arguing with a family member or debating a project proposal in a work meeting. Additionally, they use comparatively vaguer and wordier language during collaborative encounters, such as when eating lunch with a friend or relaxing in the evening with a spouse.