Barriers to Cooperative Verbal Communication

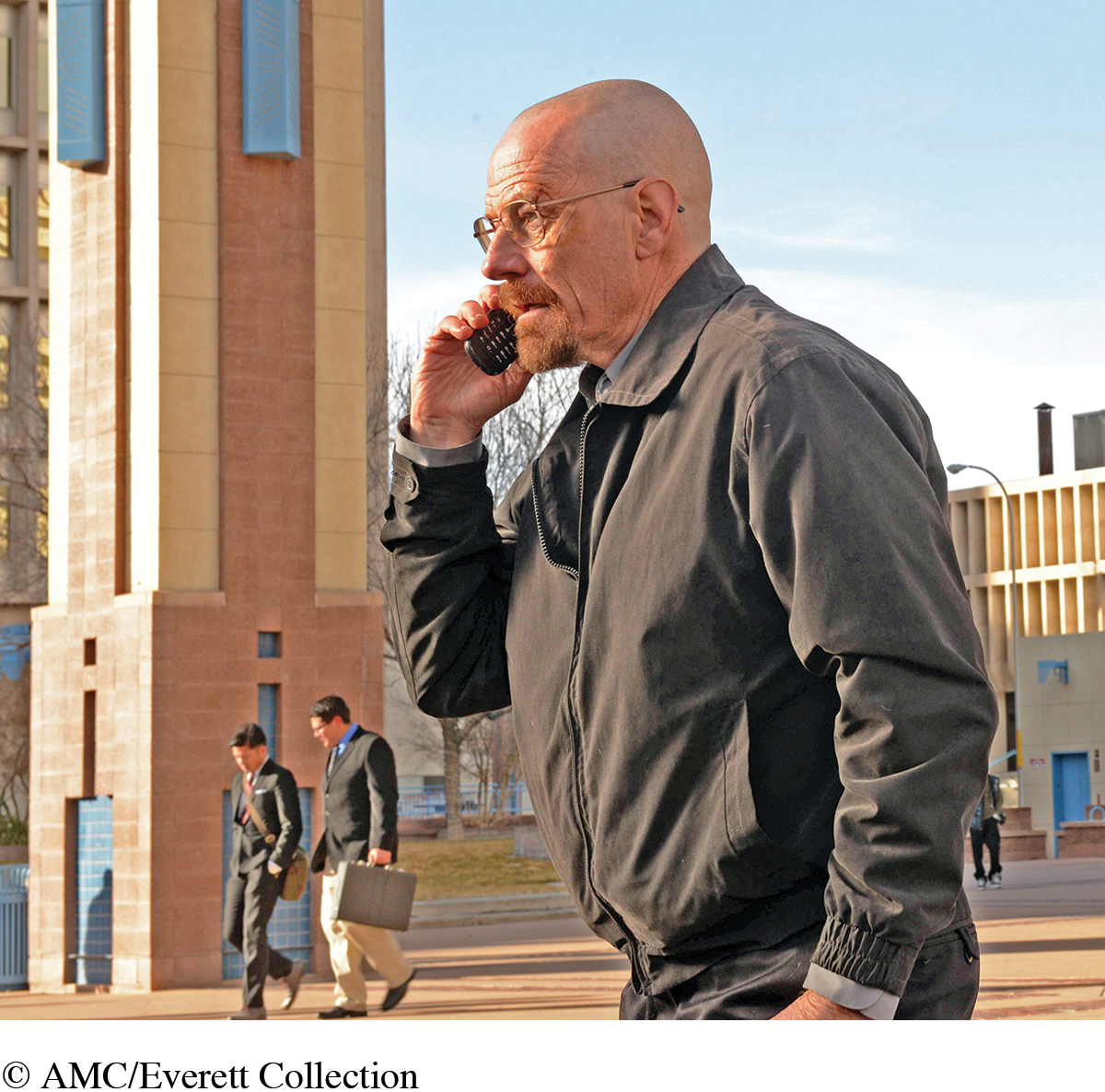

Walter White is one of the most complicated, manipulative, brilliant, and disturbing characters to ever grace the TV screen. In the critically acclaimed (and ridiculously good!) show Breaking Bad, Walter is a high school chemistry teacher who—after being diagnosed with terminal cancer—begins producing methamphetamine to raise money to cover his treatment costs and support his family following his anticipated death. As his involvement with the meth industry increases, his moral and ethical corruption deepens, leading him to lie, steal, aggress, and even murder. In season 4, Walt’s marriage to Skyler is instantly devastated by one simple disclosure: Walt has been deceiving Skyler about the degree of his criminality. When she expresses fear for his safety, he makes clear that he is not an innocent “high school teacher trying to help his family” but, instead, the perpetrator of evil:

210

Who are you talking to right now? Who is it you think you see? Do you know how much I make a year? Even if I told you, you wouldn’t believe it. Do you know what would happen if I suddenly decided to stop going into work? A business big enough to be listed on the Nasdaq goes belly up. Disappears. It ceases to exist without me. No, you clearly don’t know who you’re talking to, so let me clue you in. I am not “in danger,” Skyler. I am the danger! A guy opens his door and gets shot, and you think that of me? No! I am the one who knocks!

When used cooperatively, language can clarify understandings, build relationships, and bring us closer to others. But language also has the capacity to create divisions between people, and damage or even destroy relationships. Some people, like Walter White in Breaking Bad, use verbal communication to aggress on others, deceive them, or defensively lash out. Others are filled with fear and anxiety about interacting and therefore do not speak at all. In this section, we explore the darker side of verbal communication by looking at four common barriers to cooperative verbal communication: verbal aggression, deception, defensive communication, and communication apprehension.

VERBAL AGGRESSION

The most notable aspect of Walter White’s infamous “I am the one who knocks!” speech is its ferocity. In fact, he is so scary that his wife, Skyler, shuns him in the aftermath, out of fear for her life. Verbal aggression is the tendency to attack others’ self-concepts rather than their positions on topics of conversation (Infante & Wigley, 1986). Verbally aggressive people denigrate others’ character, abilities, or physical appearance rather than constructively discussing different points of view—for example, Walt condescendingly snarling at Skyler, “You clearly don’t know who you’re talking to, so let me clue you in.” Verbal aggression can be expressed not only through speech but also through behaviors, such as physically mocking another’s appearance, displaying rude gestures, or assaulting others (Sabourin, Infante, & Rudd, 1993). When such aggression occurs over an extended period of time and is directed toward a particular target, it can evolve into bullying.

211

Why are some people verbally aggressive? At times, such aggression stems from a temporary mental state. Most of us have found ourselves in situations at one time or another in which various factors—stress, exhaustion, frustration or anger, relationship difficulties—converge. As a result, we lose our heads and spontaneously go off on another person. Some people who are verbally aggressive suffer from chronic hostility (see Chapter 4). Others are frequently aggressive because it helps them achieve short-term interpersonal goals (Infante & Wigley, 1986). For example, people who want to cut in front of you in line, win an argument, or steal your parking spot may believe that they stand a better chance of achieving these objectives if they use insults, profanity, and threats. Unfortunately, their past experiences may bolster this belief because many people give in to verbal aggression, which encourages the aggressor to use the technique again.

If you find yourself consistently communicating in a verbally aggressive fashion, identify and address the root causes behind your aggression. Has external stress (job pressure, a troubled relationship, a family conflict) triggered your aggression? Do you suffer from chronic hostility? If you find that anger management strategies don’t help you reduce your aggression, seek professional assistance.

Communicating with others who are verbally aggressive is also a daunting challenge. Dominic Infante (1995), a leading aggression researcher, offers three tips. First, avoid communication behaviors that may trigger verbal aggression in others, such as teasing, baiting, or insulting. Second, if you know someone who is chronically verbally aggressive, avoid or minimize contact with that person. For better or worse, the most practical solution for dealing with such individuals is to not interact with them at all. Third, if you can’t avoid interacting with a verbally aggressive person, remain polite and respectful during your encounters with him or her. Allow the individual to speak without interruption. Stay calm, and express empathy (when possible). Avoid retaliating with personal attacks of your own; they will only further escalate the aggression. Finally, end interactions when someone becomes aggressive, explaining gently but firmly, “I’m sorry, but I don’t feel comfortable continuing this conversation.”

DECEPTION

Arguably the most prominent feature of Walter White’s communication in Breaking Bad is his chronic duplicity. For instance, in season 2, Walt is kidnapped by rival drug lord Tuco and consequently goes missing for several days. In the aftermath, he makes up a story about being in a “fugue state” so that his family doesn’t suspect the true reason for his absence.

When most of us think of deception, we think of messages like Walt’s to his family, in which one person communicates false information to another (“I was in a fugue state!”). But people deceive in any number of ways, only some of which involve saying untruthful things. Deception occurs when people deliberately use uninformative, untruthful, irrelevant, or vague language for the purpose of misleading others. The most common form of deception doesn’t involve saying anything false at all: studies document that concealment—leaving important and relevant information out of messages—is practiced more frequently than all other forms of deception combined (McCornack, 2008).

212

As noted in previous chapters, deception is commonplace during online encounters. People communicating on online dating sites, posting on social networking sites, and sending messages via e-mail and text message distort and hide whatever information they want, providing little opportunity for the recipients of their messages to check accuracy. Some people provide false information about their backgrounds, professions, appearances, and gender online to amuse themselves, to form alternative relationships unavailable to them offline, or to take advantage of others through online scams (Rainey, 2000).

Deception is uncooperative, unethical, impractical, and destructive. It exploits the belief on the part of listeners that speakers are communicating cooperatively—tricking them into thinking that the messages received are informative, honest, relevant, and clear when they’re not (McCornack, 2008). Deception is unethical, because when you deceive others, you deny them information that may be relevant to their continued participation in a relationship, and in so doing, you fail to treat them with respect (LaFollette & Graham, 1986). Deception is also impractical. Although at times it may seem easier to deceive than to tell the truth (McCornack, 2008), deception typically calls for additional deception. Finally, deception is destructive: it creates intensely unpleasant personal, interpersonal, and relational consequences. The discovery of deception typically causes intense disappointment, anger, and other negative emotions, and frequently leads to relationship breakups (McCornack & Levine, 1990).

213

At the same time, keep in mind that people who mislead you may not be doing so out of malicious intent. As noted earlier, many cultures view ambiguous and indirect language as hallmarks of cooperative verbal communication. In addition, sometimes people intentionally veil information out of kindness and desire to maintain the relationship, such as when you tell a close friend that her awful new hairstyle looks great because you know she’d be agonizingly self-conscious if she knew how bad it really looked (McCornack, 1997; Metts & Chronis, 1986).

DEFENSIVE COMMUNICATION

A third barrier to cooperative verbal communication is defensive communication (or defensiveness), impolite messages delivered in response to suggestions, criticism, or perceived slights. For example, at work you suggest an alternative approach to a coworker, but she snaps, “We’ve always done it this way.” You broach the topic of relationship concerns with your romantic partner, but he or she shuts you down, telling you to “Just drop it!” People who communicate defensively dismiss the validity of what another person has said. They also refuse to make internal attributions about their own behavior, especially when they are at fault. Instead, they focus their responses away from themselves and on the other person.

Four types of defensive communication are common (Waldron, Turner, Alexander, & Barton, 1993). Through dogmatic messages, a person dismisses suggestions for improvement or constructive criticism, refuses to consider other views, and continues to believe that his or her behaviors are acceptable. With superiority messages, the speaker suggests that he or she possesses special knowledge, ability, or status far beyond that of the other individual. In using indifference messages, a person implies that the suggestion or criticism being offered is irrelevant, uninteresting, or unimportant. Through control messages, a person seeks to squelch criticism by controlling the other individual or the encounter (see Table 7.3).

| Message Type | Example |

|---|---|

| Dogmatic message | “Why would I change? I’ve always done it like this!” |

| Superiority message | “I have more experience and have been doing this longer than you.” |

| Indifference message | “This is supposed to interest me?” |

| Control message | “There’s no point to further discussion; I consider this matter closed.” |

214

self-reflection

Recall a situation in which you were offered a suggestion, advice, or criticism, and you reacted defensively. What caused your reaction? What were the outcomes of your defensive communication? How could you have prevented a defensive response?

Defensive communication is interpersonally incompetent because it violates norms for appropriate behavior, rarely succeeds in effectively achieving interpersonal goals, and treats others with disrespect (Waldron et al., 1993). People who communicate in a chronically defensive fashion suffer a host of negative consequences, including high rates of conflict and lower satisfaction in their personal and professional relationships (Infante, Myers, & Burkel, 1994). Yet even highly competent communicators behave defensively on occasion. Defensiveness is an almost instinctive reaction to behavior that makes us angry—communication we perceive as inappropriate, unfair, or unduly harsh. Consequently, the key to overcoming it is to control its triggering factors. For example, if a certain person or situation invariably provokes defensiveness in you, practice preventive anger management strategies such as encounter avoidance or encounter structuring (see Chapter 4). If you can’t avoid the person or situation, use techniques such as reappraisal and the Jefferson strategy (also in Chapter 4). Given that defensiveness frequently stems from attributional errors—thinking the other person is “absolutely wrong” and you’re “absolutely right”—perception-checking (Chapter 3) can also help you reduce your defensiveness.

To prevent others from communicating defensively with you, use “I” and “we” language appropriately, and offer empathy and support when communicating suggestions, advice, or criticism. At the same time, realize that using cooperative language is not a panacea for curing chronic defensiveness in another person. Some people are so deeply entrenched in their defensiveness that any language you use, no matter how cooperative, will still trigger a defensive response. In such situations, the best you can do is strive to maintain ethical communication by treating the person with respect. You might also consider removing yourself from the encounter before it can escalate into intense conflict.

COMMUNICATION APPREHENSION

A final barrier to cooperative verbal communication is communication apprehension—fear or anxiety associated with interaction, which keeps someone from being able to communicate cooperatively (Daly, McCroskey, Ayres, Hopf, & Ayres, 2004). People with high levels of communication apprehension experience intense discomfort while talking with others and therefore have difficulty forging productive relationships. Such individuals also commonly experience physical symptoms, such as nervous stomach, dry mouth, sweating, increased blood pressure and heart rate, mental disorganization, and shakiness (McCroskey & Richmond, 1987).

skillspractice

Overcoming Apprehension

Creating communication plans to overcome communication apprehension

Think of a situation or person that triggers communication apprehension.

Envision yourself interacting in this situation or with this person.

List plan actions: topics you will discuss and messages you will present.

List plan contingencies: events that might happen during the encounter, things the other person will likely say and do, and your responses.

Implement your plan the next time you communicate in that situation or with that person.

Most of us experience communication apprehension at some point in our lives. The key to overcoming it is to develop communication plans—mental maps that describe exactly how communication encounters will unfold—prior to interacting in the situations or with the people or types of people that cause your apprehension. Communication plans have two elements. The first is plan actions, the “moves” you think you’ll perform in an encounter that causes you anxiety. Here, you map out in advance the topics you will talk about, the messages you will say in relation to these topics, and the physical behaviors you’ll demonstrate.

215

The second part of a communication plan is plan contingencies, the messages you think your communication partner or partners will present during the encounter and how you will respond. To develop plan contingencies, think about the topics your partner will likely talk about, the messages he or she will likely present, his or her reaction to your communication, and your response to your partner’s messages and behaviors.

When you implement your communication plan during an encounter that causes you apprehension, the experience is akin to playing chess. While you’re communicating, envision your next two, three, or four possible moves—your plan actions. Try to anticipate how the other person will respond to those moves and how you will respond in turn. The goal of this process is to interact with enough confidence and certainty to reduce the anxiety and fear you normally feel during such encounters.