Power and Conflict

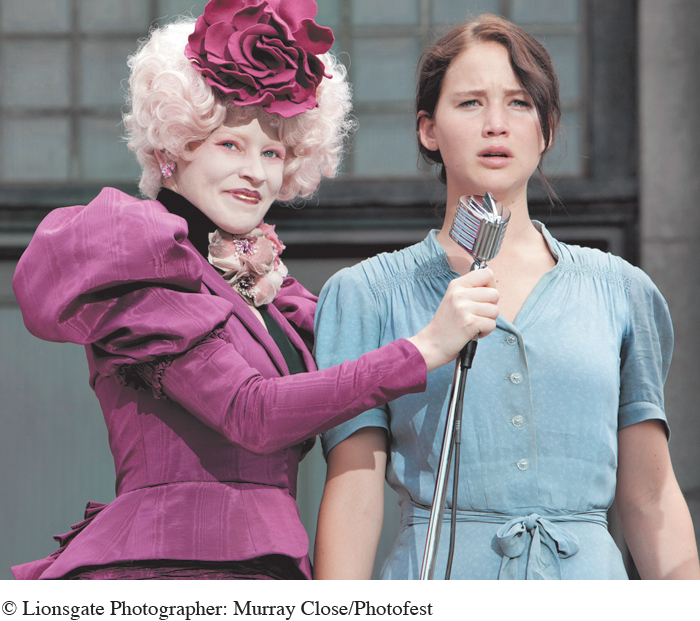

In Suzanne Collins’s futuristic novel The Hunger Games (2008), North America has become Panem, consisting of a wealthy Capitol city surrounded by twelve outlying districts.2 Following suppression of a mass rebellion by the districts, the Capitol creates the annual Hunger Games. Children from each district are selected and pitted against each other in a fight to the death that is televised live. Child participants are chosen lottery-style, and for district residents there is no choice: to not participate in the lottery means death for all. As Katniss Everdeen, the story’s central character, describes it:

Taking kids from our districts, forcing them to kill one another while we watch—this is the Capitol’s way of reminding us how totally we are at their mercy. Whatever words they use, the real message is clear: look how we take your children and sacrifice them and there’s nothing you can do. If you lift a finger, we will destroy every last one of you. (p. 18)

The dominant theme of The Hunger Games is power: the ability to influence or control people and events (Donohue & Kolt, 1992). Understanding power is critical for constructively managing conflict, because people in conflict often wield whatever power they have to overcome the opposition and achieve their goals. In conflicts in which one party has more power than the other—like the Capitol has over the districts—the more powerful tend to get what they want.

257

POWER’S DEFINING CHARACTERISTICS

Most of us won’t ever experience power wielded as brutally as in The Hunger Games. But power does permeate our everyday lives and is an integral part of interpersonal communication and relationships. Power determines how partners relate to each other, who controls relationship decisions, and whose goals will prevail during conflicts (Dunbar, 2004). Let’s consider power’s defining characteristics, as suggested by scholars William Wilmot and Joyce Hocker (2010).

self-reflection

Think of a complementary personal relationship of yours in which you have more power than the other person. How does the imbalance affect how you communicate during conflicts? Is it ethical for you to wield power over the other person during a conflict to get what you want? Why or why not?

Power Is Always Present Whether you’re talking on the phone with a parent, texting your best friend, or spending time with your lover, power is present in all your interpersonal encounters and relationships. Power may be balanced (e.g., friend to friend) or imbalanced (e.g., manager to employee, parent to young child). When power is balanced, symmetrical relationships result. When power is imbalanced, complementary relationships are the outcome.

Although power is always present, we’re typically not aware of it until people violate our expectations for power balance in the relationship, such as giving orders or talking down to us. Your dorm-floor resident adviser tells you (rather than asks you) to pick him up after class. Your work supervisor grabs inventory you were stocking and says, “No—do it this way!” even though you were doing it properly. According to Dyadic Power Theory (Dunbar, 2004), people with only moderate power are most likely to use controlling communication. Because their power is limited, they can’t always be sure they’re going to get their way. Hence, they feel more of a need to wield power in noticeable ways (Dunbar, 2004). In contrast, people with high power feel little need to display it; they know that their words will be listened to and their wishes granted. This means that you’re most likely to run into controlling communication and power-based bullying when dealing with people who have moderate amounts of power over you, such as mid-level managers, team captains, and class-project group leaders, as opposed to people with high power (in such contexts), like vice presidents, coaches, or faculty advisers.

258

Power Can Be Used Ethically or Unethically Power itself isn’t good or bad—it’s the way people use it that matters. Many happy marriages, family relationships, and long-term friendships are complementary. One person controls more resources and has more decision-making influence than the other. Yet the person in charge uses his or her power only to benefit both people and the relationship. In other relationships, the powerful partner wields his or her power unethically or recklessly. For example, a boss threatens to fire her employee unless he sleeps with her, or an abusive husband tells his unhappy wife that she’ll never see their kids again if she leaves him.

Power Is Granted Power doesn’t reside within people. Instead, it is granted by individuals or groups who allow another person or group to exert influence over them. For example, a friend of mine invited his parents to stay with him and his wife for the weekend. His parents had planned on leaving Monday, but come Monday morning, they announced that they had decided to stay through the end of the week. My friend accepted their decision even though he could have insisted that they leave at the originally agreed-on time. In doing so, he granted his parents the power to decide their departure date without his input or consent.

Power Influences Conflicts If you strip away the particulars of what’s said and done during most conflicts, you’ll find power struggles underneath. Who has more influence? Who controls the resources, decisions, and feelings involved? People struggle to see whose goals will prevail, and they wield whatever power they have to pursue their own goals. But power struggles rarely lead to mutually beneficial solutions. As we’ll see, the more constructive approach is to set aside your power and work collaboratively to resolve the conflict.

259

POWER CURRENCIES

Given that power is not innate but something that some people grant to others, how do you get power? To acquire power, you must possess or control some form of power currency, a resource that other people value (Wilmot & Hocker, 2010). Possessing or controlling a valued resource gives you influence over individuals who value that resource. Likewise, if individuals have resources you view as valuable, you will grant power to them.

Five power currencies are common in interpersonal relationships. Resource currency includes material things such as money, property, and food. If you possess material things that someone else needs or wants, you have resource power over them. Parents have nearly total resource power over young children because they control all the money, food, shelter, clothing, and other items their children need and want. Managers have high levels of resource power over employees, as they control employees’ continued employment and salaries.

Expertise currency comprises special skills or knowledge. The more highly specialized and unique the skill or knowledge you have, the more expertise power you possess. A Stuttgart-trained Porsche mechanic commands a substantially higher wage and choicer selection of clients than a minimally trained Quick Lube oil change attendant.

A person who is linked with a network of friends, family, and acquaintances with substantial influence has social network currency. Others may value his or her ability to introduce them to people who can land them jobs, talk them up to potential romantic partners, or get them invitations to exclusive parties.

Personal characteristics that people consider desirable—beauty, intelligence, charisma, communication skill, sense of humor—constitute personal currency. Even if you lack resource, expertise, and social network currency, you can still achieve a certain degree of influence and stature by being beautiful, funny, or smart.

260

Finally, you acquire intimacy currency when you share a close bond with someone that no one else shares. If you have a unique intimate bond with someone—a lover, friend, or family member—you possess intimacy power over him or her, and he or she may do you a favor “only because you are my best friend.”

POWER AND GENDER

To say that power and gender are intertwined is an understatement. Throughout history and across cultures, the defining distinction between the genders has been men’s power over women. Through patriarchy, which means “the rule of fathers,” men have used cultural practices to maintain their societal, political, and economic power (Mies, 1991). Men have built and sustained patriarchy by denying women access to power currencies.

Although many North Americans presume that the gender gap in power has narrowed, the truth is more complicated. The World Economic Forum’s 2014 report examined four “pillars” of gender equality: economic opportunity, educational access, political representation, and physical health (Bekhouche, Hausmann, Tyson, & Zahidi, 2014). Across 142 nations representing over 90 percent of the world’s population, the gaps between women and men in terms of education and health have largely been closed. Women now have 94 percent of the educational opportunities of men, and 96 percent of the health and medical support. But they still dramatically lack both economic and political power. Women have only 60 percent of the economic opportunities and resources that men share, and a paltry 21 percent of the political representation. Iceland, Finland, Norway, and Sweden top the list of the most gender-equal nations on the planet. Where do Canada and the United States rank? Nineteenth and 20th overall, but in terms of political empowerment, the United States ranks 54th and Canada, 42nd.

How does lack of power affect women’s interpersonal communication? As gender scholar Cheris Kramarae (1981) notes, women with little or no power “are not as free or as able as men are to say what they wish, when and where they wish. . . . Their talk is often not considered of much value by men” (p. 1). By contrast, what men say and do is counted as important, and women’s voices are muted. In interpersonal relationships, this power difference manifests itself in men’s tendency to expect women to listen attentively to everything they say, while men select the topics they wish to attend to when women are speaking (Fishman, 1983). Whereas men may feel satisfied that their voices are being heard in their relationships, women often feel as though their viewpoints are being ignored or minimized, both at home and in the workplace (Spender, 1990).

POWER AND CULTURE

Views of power differ substantially across cultures. Power derives from the perception of power currencies, so people are granted power not only according to which power currencies they possess but also according to the degree to which those power currencies are valued in a given culture. In Asian and Latino cultures, high value is placed on resource currency; consequently, people without wealth, property, or other such material resources are likely to grant power to those who possess those resources (Gudykunst & Kim, 2003). In contrast, in northern European countries, Canada, and the United States, people with wealth may be admired or even envied, but they are not granted unusual power. If your rich neighbor builds a huge mansion, you might be impressed. But if her new fence crosses onto your property, you’ll confront her about it (“Sorry to bother you, but your new fence is one foot over the property line”). Members of other cultures would be less likely to say anything, given her wealth and corresponding power.