Types of Friendships

363

Across our lives, each of us experiences many different types of friendships. Some are intensely close; others less so. Some are with people who seem similar to us in every conceivable way; others with those who, at least “on paper,” seem quite different. But when we consider all of the various friendships that arise and decay, two stand out from the rest as unique, challenging, and significant: best friends and cross-category friends.

BEST FRIENDS

Think of the people you consider close friends—people with whom you exchange deeply personal information and emotional support, with whom you share many interests and activities, and around whom you feel comfortable and at ease (Parks & Floyd, 1996). How many come to mind? Chances are you can count them on one hand. A study surveying over 1,000 individuals found that, on average, people have four close friends (Galupo, 2009).

But what makes a close friend a best friend? Many things. First, best friends are typically same-sex rather than cross-sex (Galupo, 2009). Although we may have close cross-sex friendships, comparatively few of these relationships evolve to being a “best.” Second, best friendship involves greater intimacy, more disclosure, and deeper commitment than does close friendship (Weisz & Wood, 2005). People talk more frequently and more deeply with best friends about their relationships, emotions, life events, and goals (Pennington, 2009). This holds true for both women and men. Third, people count on their best friends to listen to their problems without judging and to “have their back”—provide unconditional support (Pennington, 2009). Fourth, best friendship is distinct from close friendship in the degree to which shared activities commit the friends to each other in substantial ways. For example, best friends are more likely to join clubs together, participate on intramural or community sports teams together, move in together as roommates, or spend a spring break or another type of vacation together (Becker et al., 2009).

self-reflection

Call to mind your most valued social identities. Which friends provide the most acceptance, respect, and support of these identities? Which friends do you consider closest? What’s the relationship between the two? What does this tell you about the importance of identity support in determining friendship intimacy?

Finally, the most important factor that distinguishes best friends is unqualified provision of identity support: behaving in ways that convey understanding, acceptance, and support for a friend’s valued social identities. Valued social identities are the aspects of your public self that you deem the most important in defining who you are—for example, musician, athlete, poet, dancer, teacher, mother, and so on. Whoever we are—and whoever we dream of being—our best friends understand us, accept us, respect us, and support us, no matter what. Say that a close friend who is a pacifist suddenly announces that she is joining the army because she feels strongly about defending our country. What would you say to her? Or imagine that a good friend tells you that he is actually not gay but transgendered and henceforth will be living as a woman in accordance with his true gender. How would you respond? In each of these cases, best friends would distinguish themselves by supporting such identity shifts even if they found them surprising. Research following friendships across a four-year time span found that more than any other factor—including amount of communication and perceived closeness—participants who initially reported high levels of identity support from a new friend were more likely to describe that person as their best friend four years later (Weisz & Wood, 2005).

CROSS-CATEGORY FRIENDSHIPS

364

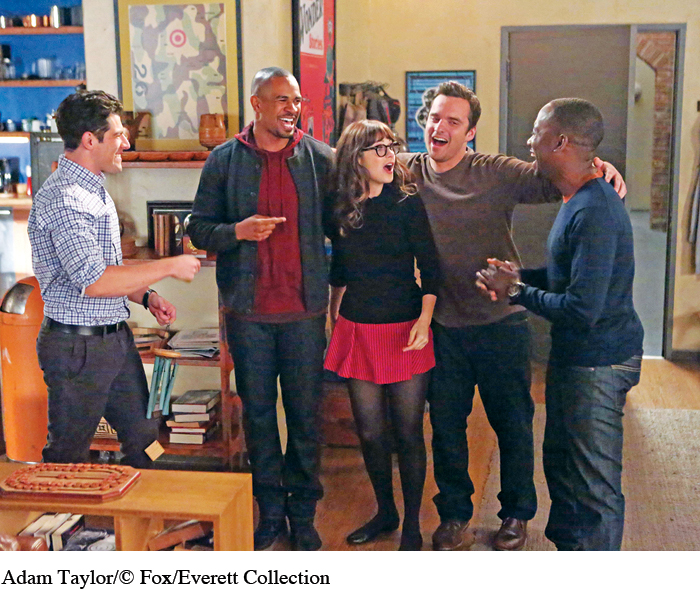

Given that friendships center on shared interests and identity support, it’s no surprise that people tend to befriend those who are similar demographically (with regard to age, gender, economic status, etc.). As just one example, studies of straight, gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgendered persons find that regardless of sexual orientation or gender identity, people are more likely to have close friendships with others of the same ethnicity (Galupo, 2009). But people also regularly defy this norm, forging friendships that cross demographic lines, known as cross-category friendships (Galupo, 2009). Such friendships are a powerful way to break down ingroup and outgroup perceptions and purge people of negative stereotypes. The four most common cross-category friendships are cross-sex, cross-orientation, intercultural, and interethnic.

Cross-Sex Friendships One of the most radical shifts in interpersonal relationship patterns over the past few decades has been the increase in platonic (nonsexual) friendships between men and women in the United States and Canada. In the nineteenth century, friendships were almost exclusively same-sex, and throughout most of the twentieth century, cross-sex friendships remained a rarity (Halatsis & Christakis, 2009). For example, a study of friendship conducted in 1974 found that, on average, men and women had few or no close cross-sex friends (Booth & Hess, 1974). However, by the mid-1980s, 40 percent of men and 30 percent of women reported having close cross-sex friendships (Rubin, 1985). By the late 1990s, 47 percent of tenth- and twelfth-graders reported having a close cross-sex friend (Kuttler, LaGreca, & Prinstein, 1999).

Most cross-sex friendships are not motivated by sexual attraction (Messman, Canary, & Hause, 1994). Instead, both men and women agree that through cross-sex friendships, they gain a greater understanding of how members of the other sex think, feel, and behave (Halatsis & Christakis, 2009). For men, forming friendships with women provides the possibility of greater intimacy and emotional depth than is typically available in male-male friendships (Monsour, 1997).

Despite changing attitudes toward cross-sex friendships, men and women face several challenges in building such relationships. For one thing, they’ve learned from early childhood to segregate themselves by sex. In many schools, young boys and girls are placed in separate gym classes, asked to line up separately for class, and instructed to engage in competitions pitting “the boys against the girls” (Thorne, 1986). It’s no surprise, then, that young children overwhelmingly prefer friends of the same sex (Reeder, 2003). As a consequence of this early-life segregation, most children enter their teens with only limited experience in building cross-sex friendships. Neither adolescence nor adulthood provides many opportunities for gaining this experience. Leisure-oriented activities such as competitive sports, community programs, and social organizations—including the Boy Scouts and Girl Scouts—are typically sex segregated (Swain, 1992).

365

Another challenge is that our society promotes same-sex friendship and cross-sex coupling as the two most acceptable relationship options for men and women. So no matter how rigorously a pair of cross-sex friends insist that they’re “just friends,” their surrounding friends and family members will likely meet these claims with skepticism or even disapproval (Monsour, 1997). Family members, if they approve of the friendship, often pester such couples to become romantically involved: “You and Jen have so much in common! Why not take things to the next level?” If families disapprove, they encourage termination of the relationship: “I don’t want people thinking my daughter is hanging out casually with some guy. Why don’t you hang out with other girls instead?” Romantic partners of people involved in cross-sex friendships often vehemently disapprove of such involvements (Hansen, 1985). Owing to constant disapproval from others and the pressure to justify the relationship, cross-sex friendships are far less stable than same-sex friendships (Berscheid & Regan, 2005).

366

Cross-Orientation Friendships A second type of cross-category friendship is cross-orientation: friendships between lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgendered, or queer (LGBTQ) people and straight men or women. As within all friendships, cross-orientation friends are bonded by shared interests and activities and provide each other with support and affection. But these friendships also provide unique rewards for the parties involved (Galupo, 2007). For straight men and women, forming a cross-orientation friendship can help correct negative stereotypes about persons of other sexual orientations and the LGBTQ community as a whole. For LGBTQ persons, having a straight friend can provide much-needed emotional and social support from outside the LGBTQ community, helping to further insulate them from societal homophobia (Galupo, 2007).

Although cross-orientation friendships are commonplace on television and in the movies, they are less frequent in real life. Although LGBTQ persons often have as many cross-orientation friends as same-orientation friends, straight men and women overwhelmingly form friendships with other straight men and women (Galupo, 2009). The principal reason is homophobia, both personal and societal. Straight persons may feel reluctant to pursue such friendships because they fear being associated with members of a marginalized group (Galupo, 2007). By far, the group that has the fewest cross-orientation friendships is straight men. In fact, the average number of cross-orientation friendships for straight men is zero: most straight men do not have a single lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgendered friend (Galupo, 2009). This tendency may perpetuate homophobic sentiments because these men are never exposed to LGBTQ persons who might amend their negative attitudes. The Focus on Culture box “Cross-Orientation Male Friendships” on page 367 explores the challenges of such relationships in depth.

focus on CULTURE: Cross-Orientation Male Friendships

Cross-Orientation Male Friendships

As New York Times writer Douglas Quenqua notes, the biggest stereotype regarding gay and straight male friendships is “the notion that gay men can’t refrain from hitting on straight friends.”1 This is false. In a poll of men involved in gay-straight friendships, Quenqua found little evidence of sexual tension. He did find several other barriers confronting such relationships, however. The most prominent was peer pressure from friends on both sides to not socialize with someone of a different orientation.

The other barriers were perceptual and communicative. Straight men often view gay men solely in terms of their sexual orientation, making it difficult to connect with them on other levels. As Matthew Streib, a gay journalist in Baltimore, describes, “It’s always about my gayness for the first two months. First they have questions, then they make fun of it, then they start seeing me as a person.” In addition, many straight men feel uncomfortable talking about their gay friends’ romantic involvements. Without being able to discuss this critical topic, the friends necessarily face constraints in how close they can become.

One context that has proven conducive to close cross-orientation friendships is the military. Sociologist Jammie Price found that the straight and gay men with the closest friendships were those who had fought side by side (1999). Having learned to depend on each other for survival built a bond that far transcended differences in sexual orientation.

But regardless of barriers or bonds, one thing is consistent in cross-orientation male friendships: lack of consistency. As Douglas Quenqua concludes, “For every sweeping statement one can make about such friendships, there is a real-life counter example to undermine the stereotypes. As with all friendships, no two are exactly alike.”

discussion questions

What are the biggest barriers blocking you from maintaining or forming cross-orientation friendships?

What, if anything, could be done to overcome these barriers?

Intercultural Friendships A third type of cross-category friendship is intercultural: friendships between people from different cultures or countries. Similar to cross-sex and cross-orientation affiliations, intercultural friendships are both challenging and rewarding (Sias et al., 2008). The challenges include overcoming differences in language and cultural beliefs, as well as negative stereotypes. Differences in language alone present a substantial hurdle. Incorrect interpretations of messages can lead to misunderstanding, uncertainty, frustration, and conflict (Sias et al., 2008). The potential rewards of intercultural friendships, however, are great and include gaining new cultural knowledge, broadening one’s worldview, and breaking stereotypes (Sias et al., 2008).

As noted throughout this chapter, the most important factor that catapults friendships forward is similarity in interests and activities. However, the defining characteristic of intercultural interactions is difference, and this makes formation of intercultural friendships more challenging (Sias et al., 2008). How can you overcome this? By finding, and then bolstering, some significant type of ingroup similarity. For example, a good friend—who is Japanese—and I—of Irish descent—founded our friendship on a shared love of EDM (electronic dance music). But the strongest predictor of whether someone will have an intercultural friendship is prior intercultural friendships. People who have had close friends from different cultures in the past are substantially more likely to forge such friendships in the future (Sias et al., 2008). This is because they learn the enormous benefits that such relationships provide, and lack fear and uncertainty about “outgroupers.”

367

Interethnic Friendships The final type of cross-category friendship is an interethnic friendship: a bond between people who share the same cultural background (for example, American) but who are of different ethnic groups (African American, Asian American, Euro-American, and so forth). Similar to cross-orientation and intercultural friendships, interethnic friendships boost cultural awareness and commitment to diversity (Shelton, Richeson, & Bergsieker, 2009). In addition, interethnic friends apply these outcomes broadly. People who develop a close interethnic friendship become less prejudiced toward ethnicities of all types as a result (Shelton et al., 2009).

The most difficult barriers people face in forming interethnic friendships are attributional and perceptual errors. Too often we let our own biases and stereotypes stop us from having open, honest, and comfortable interactions with people from other ethnic groups. We become overly concerned with the “correct” way to act and thus end up behaving nervously. Such nervousness may lead to awkward, uncomfortable encounters and may cause us to avoid interethnic encounters in the future, dooming ourselves to friendship networks that lack diversity (Shelton et al., 2010).

368

How can you overcome these challenges and improve your ability to form interethnic friendships? Review Chapter 3’s discussion of attributional errors and perception-checking. Look for points of commonality during interethnic encounters that might lead to the formation of a friendship—such as a shared interest in music, fashion, sports, movies, or video games. Keep in mind that sometimes encounters are awkward, people don’t get along, and friendships won’t arise—and it has nothing to do with ethnic differences.