Maintaining Friendships

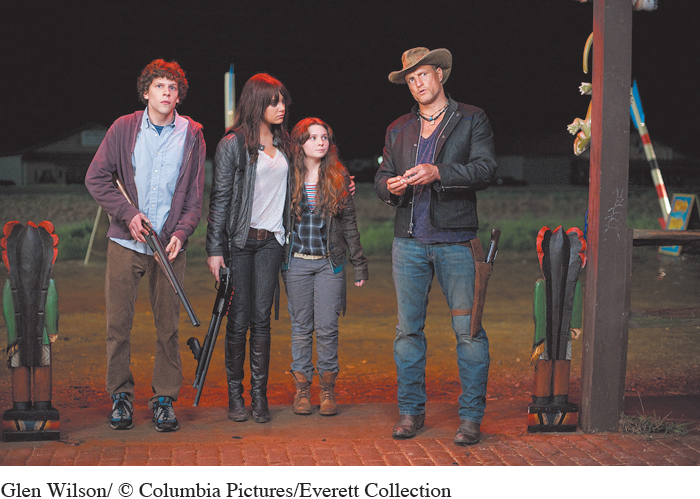

In the movie Zombieland (2009), four people known by the monikers of their former hometowns struggle to survive in a postapocalyptic world (Fleischer, Reesee, & Werrick, 2009). The central character, Columbus, is a self-described loner who never had close ties to friends or family. As he puts it, “I avoided people like they were zombies, even before they were zombies!” To deal with the challenge of constant flesh-eater attacks, he develops a set of rules, including Rule #1: Cardio (stay in shape to stay ahead of zombies); Rule #17: Don’t be a hero (don’t put yourself at risk to save others); and Rule #31: Always check the backseat (to avoid surprises). As time passes, he bands together with three other survivors—Tallahassee, Wichita, and Little Rock—and learns that they, too, have trust issues, regrets regarding their former lives, and fears about the future (above and beyond zombie attacks). As they travel across the country together, they learn to trust, support, defend, and depend on one another. This leads to a friendship that eventually deepens to a family-like bond. Columbus even chooses to bend Rule #17 to save Wichita, by being a hero. As he narrates in the final scene, “Those smart girls in the big black truck and that big guy in that snakeskin jacket—they were the closest to something I’d always wanted, but never really had—a family. I trusted them and they trusted me. Even though life would never be simple or innocent again, we had hope—we had each other. And without other people, well, you might as well be a zombie!”

369

It’s true. We need our friends. Most of us don’t need them for survival, as we don’t face daily zombie attacks. But our friends do provide a constant and important shield against the stresses, hardships, and threats of our everyday lives. We count on friends to be there when we need them and to provide support; in return, we do the same. This is what bonds us together.

At the same time, friendships don’t endure on their own. As with romantic and family involvements, friendships flourish only when you consistently communicate in ways that maintain them. Two ways that we keep friendships alive are by following friendship rules and by using maintenance strategies.

FOLLOWING FRIENDSHIP RULES

In Zombieland, Columbus follows a set of rules that allow him to survive. In the real world, one of the ways we can help our friendships succeed is by following friendship rules—general principles that prescribe appropriate communication and behavior within friendship relationships (Argyle & Henderson, 1984). In an extensive study of friendship maintenance, social psychologists Michael Argyle and Monica Henderson observed 10 friendship rules that people share across cultures. Both men and women endorse these rules, and adherence to them distinguishes happy from unhappy friendships (Schneider & Kenny, 2000). Not abiding by them may even cost you your friends: people around the globe describe failed friendships as ones that didn’t follow these rules (Argyle & Henderson, 1984). The 10 rules for friendship are:

self-reflection

Consider the 10 universal rules that successful friends follow. Which of these rules do you abide by in your own friendships? Which do you neglect? How has neglecting some of these rules affected your friendships? What steps might you take to better follow rules you’ve previously neglected?

Show support. Within a friendship, you should provide emotional support and offer assistance in times of need, without having to be asked (Burleson & Samter, 1994). You also should accept and respect your friend’s valued social identities. When he or she changes majors, tries out for team captain, or opts to be a stay-at-home mom or dad, support the decision—even if it’s one you yourself wouldn’t make.

Seek support. The flip side of the first rule is that when you’re in a friendship, you should not only deliver support but seek support and counsel when needed, disclosing your emotional burdens to your friends. Other than sharing time and activities, mutual self-disclosure serves as the glue that binds friendships together (Dainton, Zelley, & Langan, 2003).

370

Respect privacy. At the same time that friends anticipate both support and disclosure, they also recognize that friendships have more restrictive boundaries for sharing personal information than do romantic or family relationships. Recognize this, and avoid pushing your friend to share information that he or she considers too personal. Also resist sharing information about yourself that’s intensely private or irrelevant to your friendship.

Keep confidences. A critical feature of enduring friendships is trust. When friends share personal information with you, do not betray their confidence by sharing it with others.

Defend your friends. Part of successful friendships is the feeling that friends have your back. Your friends count on you to stand up for them, so defend them when they are being attacked—whether it’s online or off, face-to-face or behind their back.

Avoid public criticism. Friends may disagree or even disapprove of each other’s behavior on occasion. But airing your grievances publicly in a way that makes a friend look bad will only hurt your friendship. Avoid communication such as questioning a friend’s loyalty in front of other friends or commenting on a friend’s weight in front of a salesperson.

Make your friends happy. An essential ingredient to successful friendships is striving to make your friends feel good while you’re in their company. You can do this by practicing positivity: communicating with them in a cheerful and optimistic fashion, doing unsolicited favors for them, and buying or making gifts for them.

Manage jealousy. Unlike long-term romantic relationships, most friendships aren’t exclusive. Your close friends will likely have other close friends, perhaps even friends who are more intimate with them than you are. Accept that each of your friends has other good friends as well, and constructively manage any jealousy that arises in you.

Share humor. Successful friends spend a good deal of their time joking with and teasing each other in affectionate ways. Enjoying a similar sense of humor is an essential aspect of most long-term friendships.

Maintain equity. In enduring, mutually satisfying friendships, the two people give and get in roughly equitable proportions (Canary & Zelley, 2000). Help maintain this equity by conscientiously repaying debts, returning favors, and keeping the exchange of gifts and compliments balanced.

skillspractice

Friendship Maintenance

Using interpersonal communication to maintain a friendship

Think of a valued friendship you wish to maintain.

Make time each week to talk with this person, whether online or face-to-face.

Have fun together and share stories.

Let your friend know that you accept and respect his or her valued social identities.

Encourage disclosure of thoughts and feelings.

Avoid pushing for information that he or she considers too personal.

Negotiate boundaries around topics that are best avoided.

Don’t share secrets disclosed by your friend with others.

Provide emotional support and assistance when needed, without having to be asked.

Defend your friend online and off.

MAINTENANCE STRATEGIES FOR FRIENDS

Most friendships are built on a foundation of shared activities and self-disclosure. To maintain your friendships, strive to keep this foundation solid by regularly doing things with your friends and making time to talk.

371

Sharing Activities Through sharing activities, friends structure their schedules to enjoy hobbies, interests, and leisure activities together. But even more important than the actual sharing of activities is the perception that each friend is willing to make time for the other. Scholar William Rawlins notes that even friends who don’t spend much time together can still maintain a satisfying connection as long as each perceives the other as “being there” when needed (Rawlins, 1994).

Of course, most of us have several friends but only finite amounts of time available to devote to each one. Consequently, we are often put in positions in which we have to choose between time and activities shared with one friend versus another. Unfortunately, given the significance that sharing time and activities together plays in defining friendships, your decisions regarding with whom you invest your time will often be perceived by friends as communicating depth of loyalty (Baxter et al., 1997). In cases in which you choose one friend over another, the friend not chosen may view your decision as disloyal. To avert this, draw on your interpersonal communication skills. Express gratitude for the friend’s offer, assure him or her that you very much value the relationship, and make concrete plans for getting together another time.

Self-Disclosure A second strategy for friendship maintenance is self-disclosure. All friendships are created and maintained through the discussion of thoughts, feelings, and daily life events (Dainton et al., 2003). To foster disclosure with your friends, routinely make time just to talk—encouraging them to share their thoughts and feelings about various issues, whether online or face-to-face. Equally important, avoid betraying friends—sharing with others personal information friends have disclosed to you.

372

As with romantic and family relationships, it’s important to balance openness in self-disclosure with protection (Dainton et al., 2003). Over time, most friends learn that communication about certain issues, topics, or even people is best avoided to protect the relationship and preclude conflict. As a result, friends negotiate communicative boundaries that allow their time together and communication shared to remain positive. Such boundaries can be perfectly healthy as long as both friends agree on them and the issues being avoided aren’t central to the survival of the friendship. For example, several years ago a male friend of mine began dating someone who I thought treated him badly. His boyfriend, whom I’ll call “Mike,” had a very negative outlook, constantly complained about my friend, and belittled him and their relationship in public. I thought Mike’s communication was unethical and borderline abusive. But whenever I expressed my concern, my buddy grew defensive. Mike just had an “edge” to his personality, my friend said, and I “didn’t know the real Mike.” After several such arguments, we agreed that, for the sake of our friendship, the topic of Mike was off-limits. We both respected this agreement—thereby protecting our friendship—until my friend broke up with Mike. After that, we opened the topic once more to free and detailed discussion.