There are nine categories of terrestrial biomes

Terrestrial biomes are traditionally placed into nine categories. In this section, we will take a tour of the biomes. We start with tundras and boreal forests, which have average annual temperatures of less than 5°C. We will then examine the biomes in temperate regions, with average temperatures between 5°C and 20°C. Finally, we will explore the biomes of tropical regions, which have average annual temperatures of more than 20°C. As we will see, seasonal patterns and amounts of precipitation can differ a great deal within a given temperature range, producing different types of biomes.

142

Tundras

Tundra The coldest biome, characterized by a treeless expanse above permanently frozen soil.

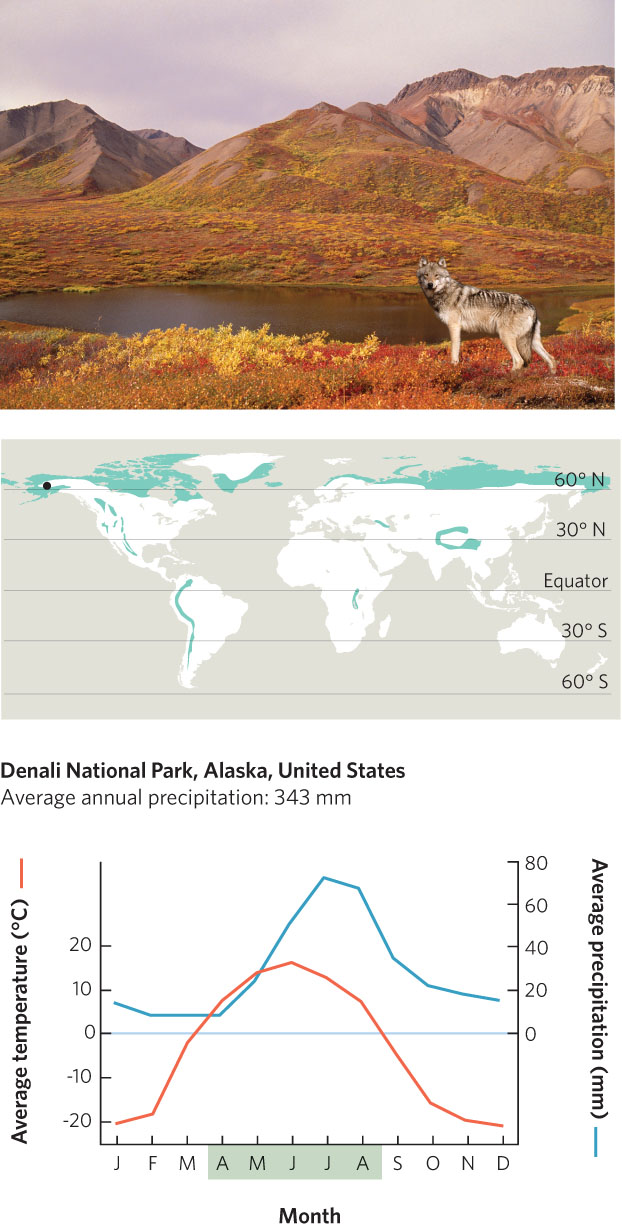

The tundra, shown in Figure 6.5, is the coldest biome and is characterized by a treeless expanse above permanently frozen soil, or permafrost. The soils thaw to a depth of 0.5 to 1 m during the brief summer growing season. Annual precipitation is generally less, and often much less, than 600 mm, but in low-lying areas where permafrost prevents drainage, soils may remain saturated with water throughout most of the growing season. Soils tend to be acidic because of their high content of organic matter, and they contain few nutrients. In this nutrient-poor environment, plants hold their foliage for years. Most plants are dwarf, prostrate woody shrubs, which grow low to the ground to gain protection under the winter blanket of snow and ice, since anything protruding above the surface of the snow is sheared off by blowing ice crystals. For most of the year, the tundra is an exceedingly harsh environment, but during summer days with 24 hours of sunlight, there is a rush of biological activity.

Tundra is found in the Arctic regions of Russia, Canada, Scandinavia, and Alaska, and in the Antarctic regions along the edge of Antarctica and nearby islands. At high elevations within temperate latitudes, even within the tropics, one finds vegetation resembling that of Arctic tundra, including some of the same species or their close relatives. These areas of alpine tundra above the tree line occur widely in the Rocky Mountains of North America, the Alps of Europe, and, especially, on the Plateau of Tibet in central Asia. In spite of their similarities, alpine and Arctic tundra have important differences. Areas of alpine tundra generally have warmer and longer growing seasons, higher precipitation, less severe winters, greater productivity, better-drained soils, and higher species diversity than Arctic tundra. Still, harsh winter conditions ultimately limit the growth of trees.

Boreal Forests

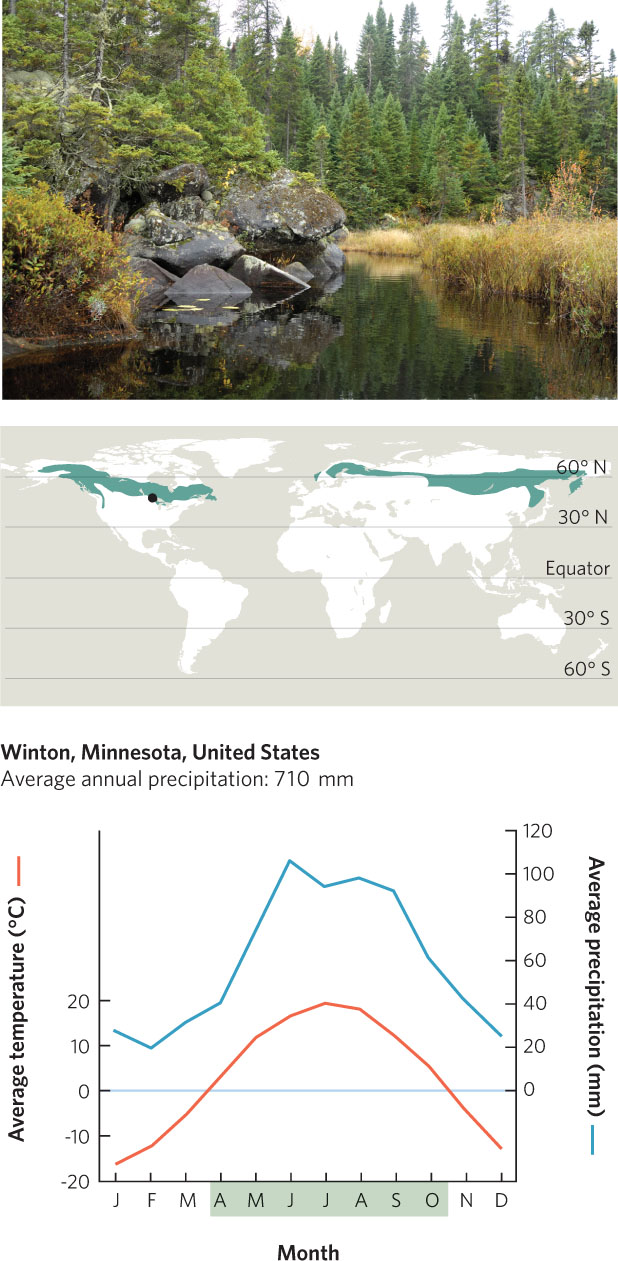

Stretching in a broad belt centered at about 50° N in North America and about 60° N in Europe and Asia lies the boreal forest. As shown in Figure 6.6, the boreal forest, sometimes called taiga, is a biome densely populated by evergreen needle-leaved trees, with a short growing season and severe winters. The average annual temperature is below 5°C. Annual precipitation generally ranges between 40 and 1,000 mm, and because evaporation is low, soils are moist throughout most of the growing season. The vegetation consists of dense, seemingly endless stands of 10 to 20 m tall evergreen needle-leaved trees, mostly spruces and firs. Because of the low temperatures, plant litter decomposes very slowly and accumulates at the soil surface, forming one of the largest reservoirs of organic carbon on Earth. The needle litter produces high levels of organic acids, so the soils are acidic, strongly podsolized, and generally of low fertility. Growing seasons rarely exceed 100 days, and are often half that long. The vegetation is extremely frost-tolerant; temperatures may reach −60°C during the winter. Since few species can survive in such harsh conditions, species diversity is very low. The boreal forest is not well suited for agriculture, but it serves as a source of timber products that include lumber and paper.

143

Boreal forest A biome densely populated by evergreen needle-leaved trees, with a short growing season and severe winters. Also known as Taiga.

Temperate Rainforests

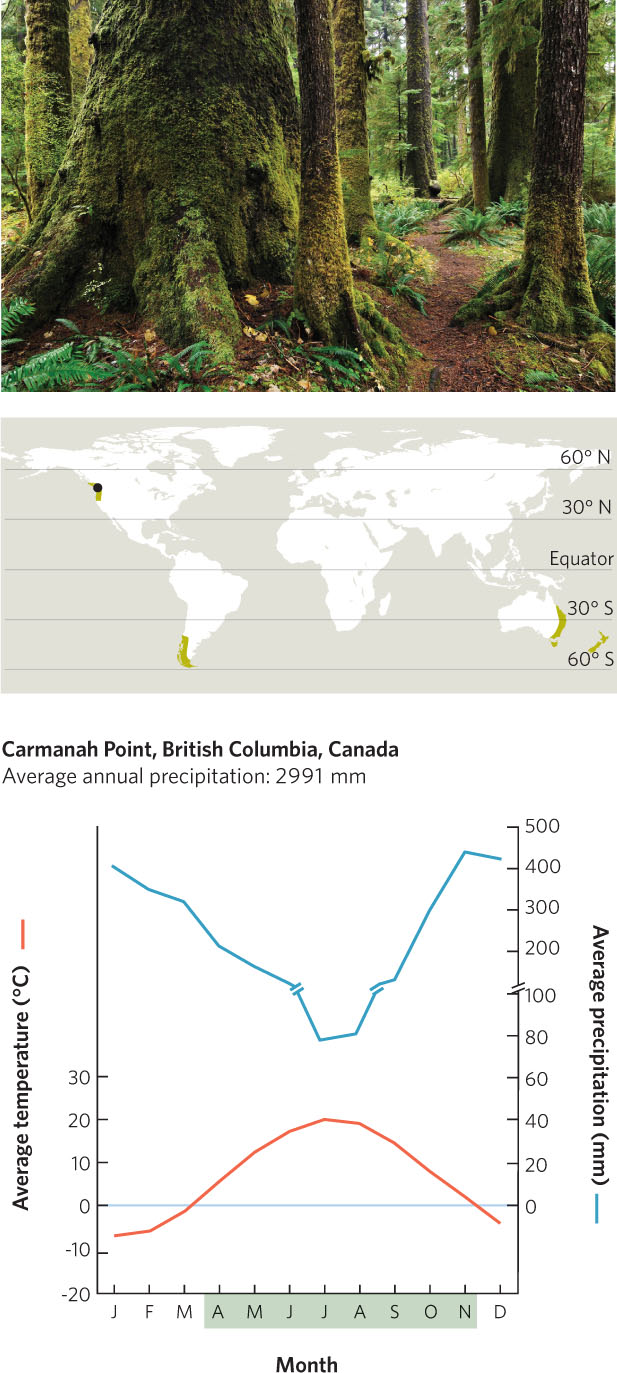

As we begin to move closer to the equator, we find the four temperate biomes: temperate rainforest, temperate seasonal forest, woodland/shrubland, and temperate grassland/cold desert. The temperate rainforest biome, shown in Figure 6.7, is known for mild temperatures and abundant precipitation, and is dominated by evergreen forests. These conditions are due to nearby warm ocean currents. This biome is most extensive near the Pacific coast in northwestern North America and in southern Chile, New Zealand, and Tasmania. The mild, rainy winters and foggy summers create conditions that support evergreen forests. In North America, these forests are dominated toward the south by coast redwood (Sequoia sempervirens) and toward the north by Douglas-fir. These trees are typically 60 to 70 m tall and may grow to over 100 m, making them very attractive for harvesting as lumber. Ecologists do not understand why these sites are dominated by needle-leaved trees, but the fossil record shows that these plant communities are very old and that they are remnants of forests that were vastly more extensive 70 million years ago. In contrast to tropical rainforests, temperate rainforests typically support few species.

Temperate rainforest A biome known for mild temperatures and abundant precipitation, and dominated by evergreen forests.

144

Temperate Seasonal Forests

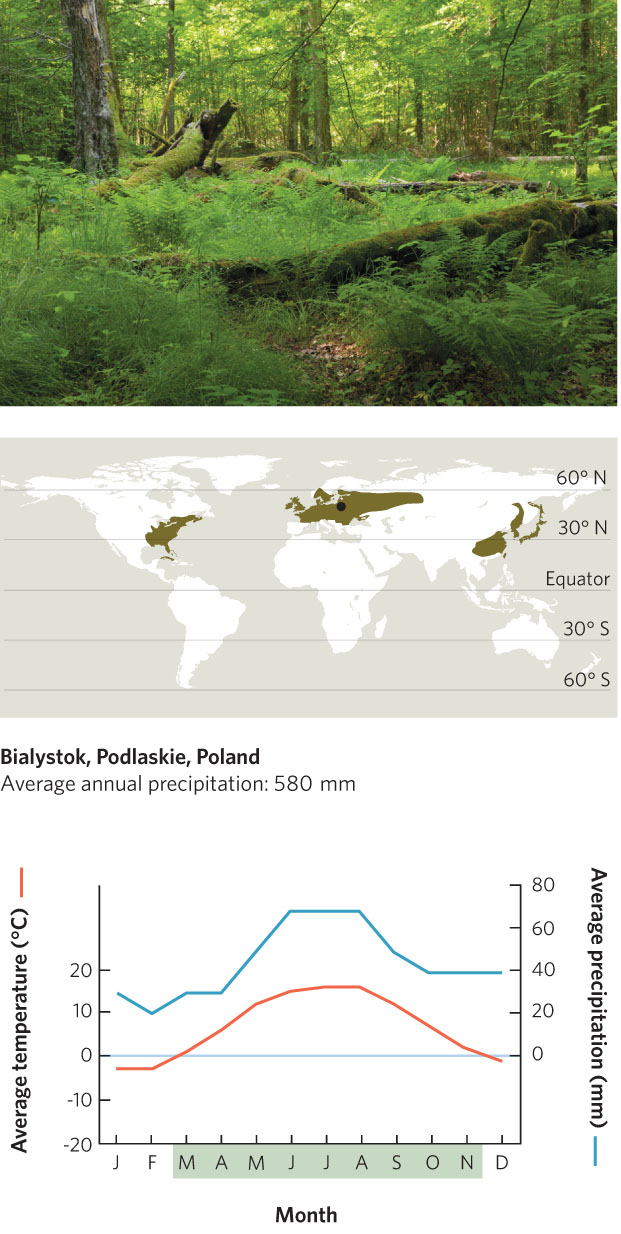

The temperate seasonal forest biome, shown in Figure 6.8, occurs under moderate temperature and precipitation conditions, and is dominated by deciduous trees. Winter temperatures can drop below freezing in this biome. The environmental conditions in this biome fluctuate much more than they do in the temperate rainforests because they do not benefit from the moderating effects of nearby warm ocean waters. In North America, the dominant plant growth form is deciduous trees, which lose their leaves each fall and include maple, beech, and oak. In North America, this biome stretches across the eastern United States and southeastern Canada; it is also widely distributed in Europe and eastern Asia. This biome is not common in the Southern Hemisphere where the larger ratio of ocean surface to land moderates winter temperatures at high altitudes and prevents frost.

Temperate seasonal forest A biome with moderate temperature and precipitation conditions, dominated by deciduous trees.

In the Northern Hemisphere, the length of the growing season in this biome varies from 130 days at higher latitudes to 180 days at lower latitudes. Precipitation usually exceeds evaporation and transpiration; consequently, water tends to move downward through soils and to drain from the landscape as groundwater and as surface streams and rivers. Soils are often podsolized, tend to be slightly acidic and moderately leached, and, because of abundant organic matter, are brown in color. The vegetation often includes a layer of smaller tree species and shrubs beneath the dominant trees, as well as herbaceous plants on the forest floor. Many of these herbaceous plants complete their growth and flower in early spring before the trees have fully leafed out.

Warmer and drier parts of the temperate seasonal forest biome, especially where soils are sandy and nutrient poor, tend to develop needle-leaved forests dominated by pines. The most important of these ecosystems in North America are the pine forests of the coastal plains of the Atlantic and Gulf coasts of the United States; pine forests also exist at higher elevations in the western United States. Because of the warm climate in the southeastern United States, soils there are usually nutrient poor. The low availability of nutrients and water favors evergreen, needle-leaved trees, which resist desiccation and give up nutrients slowly because they retain their needles for several years. Soils in this biome tend to be dry and fires are frequent, although most species are able to resist fire damage. The temperate seasonal forest was one of the first biomes that European settlers in North America used for agriculture.

145

Woodlands/Shrublands

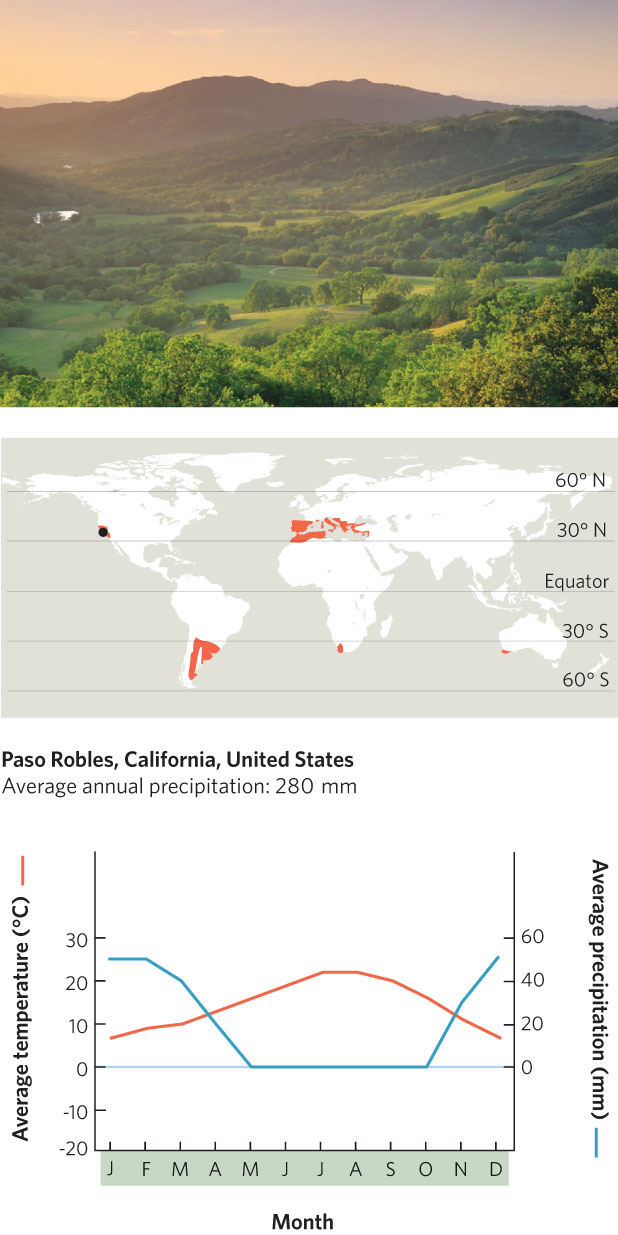

The woodland/shrubland biome, shown in Figure 6.9, is characterized by hot, dry summers and mild, wet winters, a combination that favors the growth of drought-tolerant grasses and shrubs. Because this type of climate is found around much of the Mediterranean Sea, it is often referred to as a Mediterranean climate regardless of where it is actually found. The woodland/shrubland biome has many different regional names including chaparral in southern California, matorral in southern South America, fynbos in southern Africa, and maquis in the area surrounding the Mediterranean Sea.

woodland/shrubland A biome characterized by hot, dry summers and mild, wet winters, a combination that favors the growth of drought-tolerant grasses and shrubs.

Sclerophyllous Vegetation that has small, durable leaves.

As you can see in the climate diagram, although there is a 12-month growing season, plant growth is limited by dry conditions in the summer and by cold temperatures in the winter. This biome supports thick evergreen shrubby vegetation 1 to 3 m in height, with deep roots and drought-resistant foliage. The small, durable leaves of typical Mediterranean-climate plants have earned them the label of sclerophyllous (“hard-leaved”) vegetation. Fires are frequent in the woodland/shrubland biome, and most plants have either fire-resistant seeds or root crowns that resprout soon after a fire. Traditional human use of this biome has been for grazing animals and growing deep-rooted crops such as grapes.

Temperate Grasslands/Cold Deserts

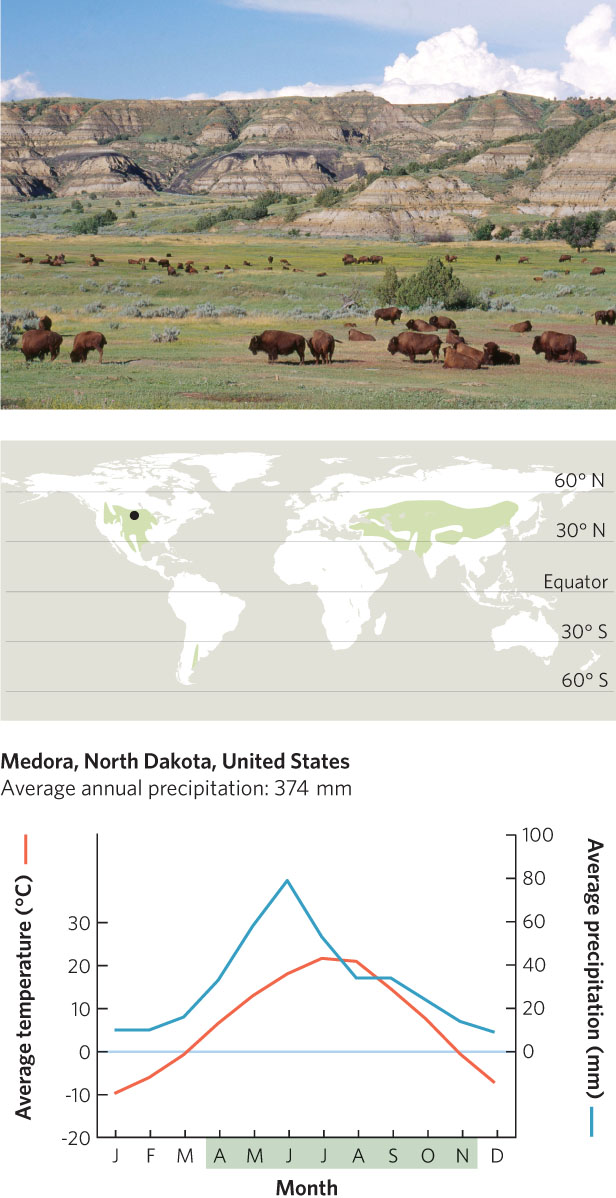

The temperate grassland/cold desert biome, shown in Figure 6.10, is characterized by hot, dry summers and cold, harsh winters, and is dominated by grasses, nonwoody flowering plants, and drought-adapted shrubs. Plant growth is constrained by a lack of precipitation in the summer and by cold temperatures in the winter. The biome is also known by a variety of different names around the world, including prairies in North America, pampas in South America, and steppes in eastern Europe and central Asia.

Temperate grassland/cold desert A biome characterized by hot, dry summers and cold, harsh winters and dominated by grasses, nonwoody flowering plants, and drought-adapted shrubs.

As the biome name suggests, the dominant plant forms in temperate grasslands are grasses and nonwoody flowering plants that are well adapted to the frequent fires. Precipitation varies widely across this biome. For example, on the eastern edge of North American prairies, annual precipitation can be 1,000 mm. In such areas, grasses can grow to more than 2 m high and are referred to as tallgrass prairies. There is even enough moisture in such areas to support the growth of trees, but the frequent fires prevent the trees from becoming a dominant component of this biome. As one moves west, annual precipitation declines to 500 mm or less. In these areas, grasses generally do not grow taller than 0.5 m and are referred to as shortgrass prairies. Because precipitation is infrequent, organic detritus does not decompose rapidly and this makes the soils rich in organic matter. In addition, the low acidity of the soils means that they are not heavily leached and they tend to be rich in nutrients.

Even farther west in North America, annual precipitation drops below 250 mm and the temperate grasslands grade into cold deserts, also known as temperate deserts. In the United States, the cold desert extends across most of the Great Basin, which sits in the rain shadow of the Sierra Nevada and Cascade Mountains. In the northern part of the region, the dominant plant is sagebrush, whereas toward the south and on somewhat moister soils, widely spaced juniper and piñon trees predominate, forming open woodlands with trees less than 10 m in stature and sparse coverings of grass. In these cold deserts, evaporation and transpiration exceed precipitation during most of the year, so soils are dry. Fires are infrequent in cold deserts because the habitat produces little organic matter to burn. However, because of the low productivity of the plant community, grazing can exert strong pressure on the vegetation and may even favor the persistence of shrubs, which are not good forage. Indeed, many dry grasslands in the western United States and elsewhere in the world have been converted to deserts by overgrazing.

146

Tropical Rainforests

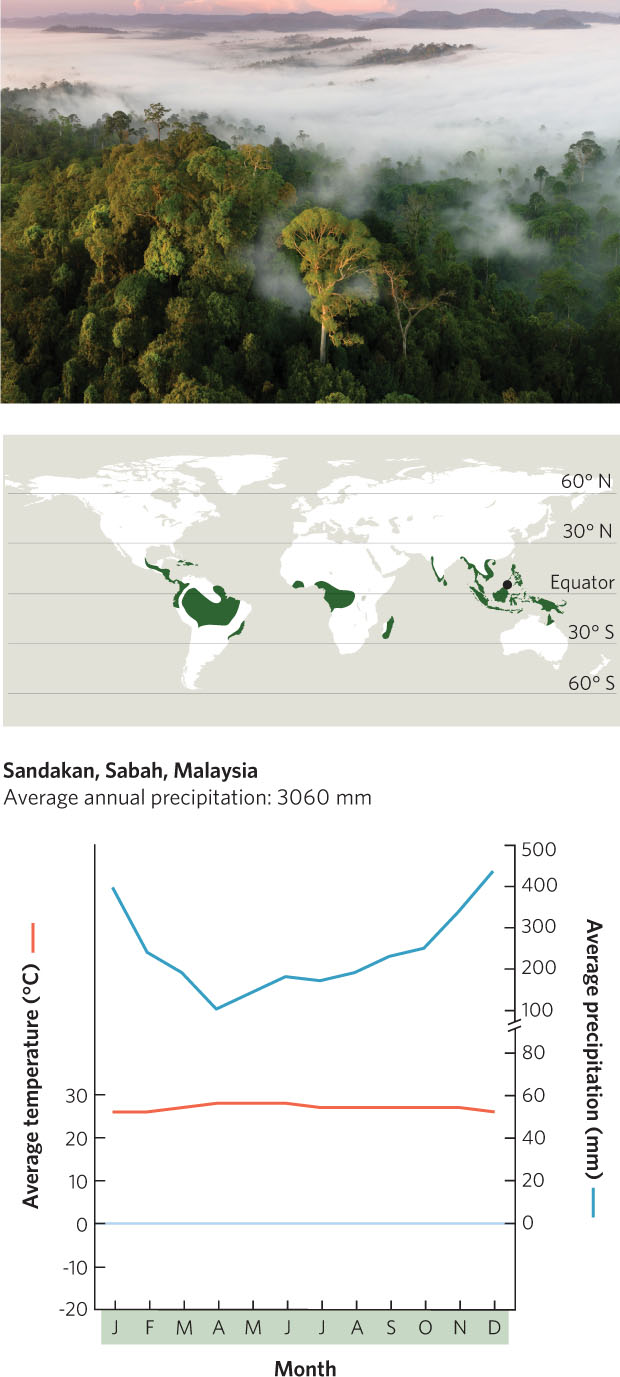

Our final group of biomes is found in areas of tropical temperatures and includes tropical rainforests, tropical seasonal forests/savannas, and subtropical deserts. Tropical rainforests, shown in Figure 6.11, fall within 20° N and 20° S of the equator, are warm and rainy, and are characterized by multiple layers of lush vegetation. Tropical rainforests have a continuous canopy of 30 to 40 m trees with emerging trees that occasionally reach 55 m. Shorter trees and shrubs form a layer known as the understory below the canopy. The understory also contains an abundance of epiphytes and vines. Species diversity is higher in tropical rainforests than anywhere else on Earth. This biome occurs in much of Central America, the Amazon basin, the Congo in southern West Africa, the eastern side of Madagascar, Southeast Asia, and the northeast coast of Australia. In many of these locations, however, much of the rainforest has been destroyed to harvest lumber and to make room for agriculture.

Tropical rainforest A warm and rainy biome, characterized by multiple layers of lush vegetation.

Climates that support tropical rainforests are always warm and receive at least 2,000 mm of precipitation throughout the year, with rarely less than 100 mm during any single month. The tropical rainforest climate often exhibits two peaks of rainfall centered on the equinoxes, corresponding to the periods when the intertropical convergence zone passes over the equator. Rainforest soils are typically old and deeply weathered. Because they are relatively devoid of humus and clay, they take on the reddish color of aluminum and iron oxides and they retain nutrients poorly. Despite the poor ability of these soils to hold nutrients, the biological productivity of tropical rainforests per unit area exceeds that of any other terrestrial biome. Moreover, the standing biomass exceeds that of all other biomes except temperate rainforests. This tremendous growth is possible because the continuously high temperatures and abundant moisture causes organic matter to decompose quickly, and vegetation immediately takes up the released nutrients. While rapid nutrient cycling supports the high productivity of the rainforest, it also makes the rainforest ecosystem extremely vulnerable to disturbance. When tropical rainforests are cut and burned, many of the nutrients are carted off in logs or go up in smoke. The vulnerable soils erode rapidly and fill the streams with silt. In many cases, the environment degrades rapidly and the landscape becomes unproductive.

147

Tropical Seasonal Forests/Savannas

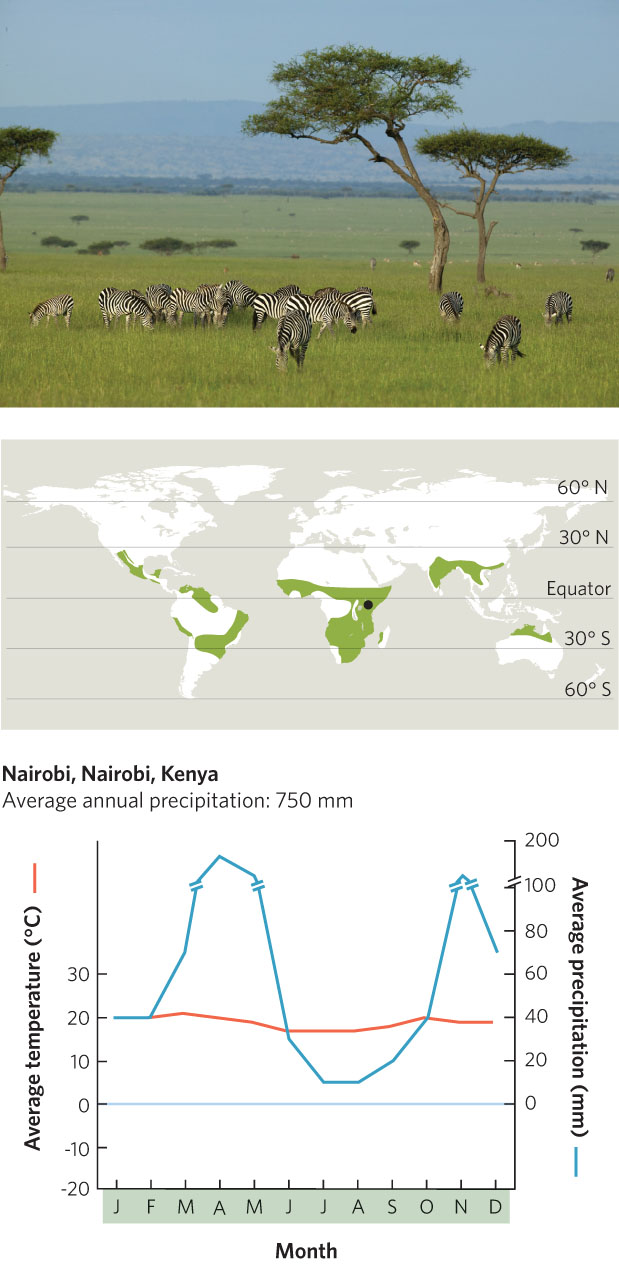

Tropical seasonal forest A biome with warm temperatures and pronounced wet and dry seasons, dominated by deciduous trees that shed their leaves during the dry season.

Tropical seasonal forests, shown in Figure 6.12, are located mostly beyond 10° N and 10° S of the equator. These regions experience warm temperatures and, as the intertropical convergence zone moves during the year, pronounced wet and dry seasons. Because tropical seasonal forests have a preponderance of deciduous trees that shed their leaves during the dry season, this biome is sometimes referred to as a tropical deciduous forest. In areas where the dry season is longer and more severe, the vegetation becomes shorter and develops thorns to protect leaves from grazing animals. With even longer dry periods, the vegetation grades from dry forest into thorn forest and finally into savannas, which are open landscapes containing grasses and occasional trees, including acacia and baobab trees.

148

The tropical seasonal forest/savanna biome occurs in Central America, the Atlantic coast of South America, sub-Saharan Africa, southern Asia, and northwestern Australia. Fire and grazing play important roles in maintaining the character of the savanna biome. Under these conditions, grasses can persist better than other forms of vegetation. When grazing and fire are prevented within a savanna habitat, dry forest often begins to develop. As in more humid tropical environments, the soils tend to hold nutrients poorly but the warm temperatures favor rapid decomposition. Rapid decomposition provides a rapid recycling of nutrients into the soil, which trees can quickly take up and use for growth and reproduction. This rapid cycling of nutrients also makes this biome an attractive place for agriculture, including raising cattle. On the Pacific coast of Central America and on the Atlantic coast of South America, for example, over 99 percent of this biome has been converted to agriculture.

Subtropical Deserts

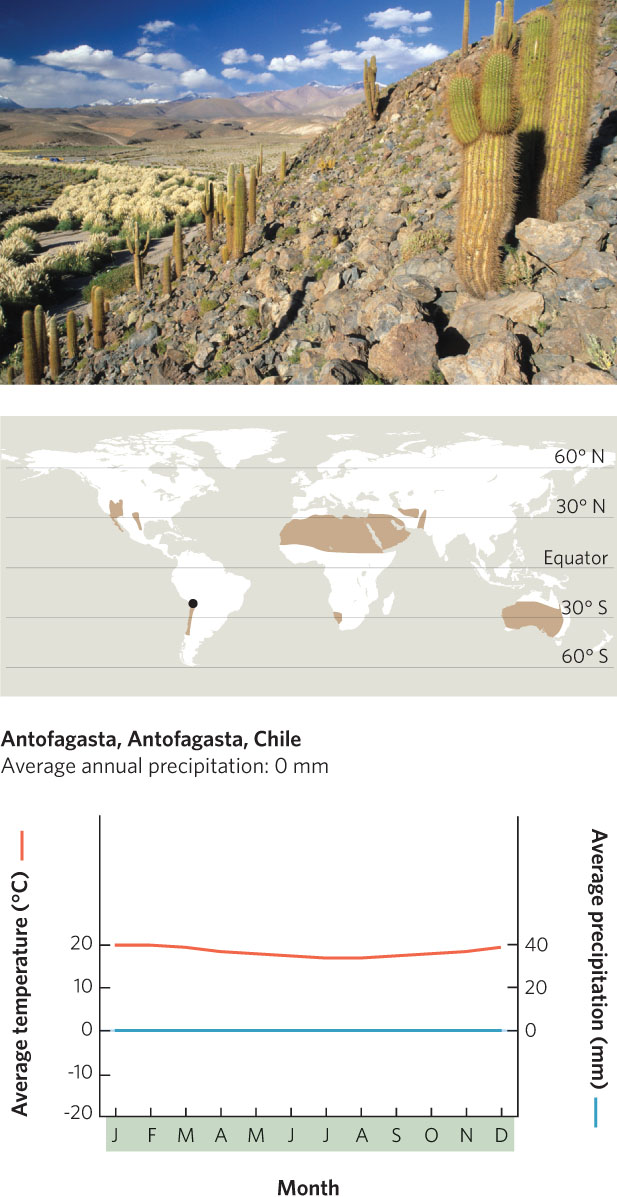

Subtropical desert A biome characterized by hot temperatures, scarce rainfall, long growing seasons, and sparse vegetation.

Subtropical deserts, shown in Figure 6.13, are characterized by hot temperatures, scarce rainfall, long growing seasons, and sparse vegetation. Also known as hot deserts, subtropical deserts develop at 20° to 30° north and south of the equator, in areas associated with the dry, descending air of Hadley cells. Subtropical deserts include the Mojave Desert in North America, the Sahara Desert in Africa, the Arabian Desert in the Middle East, and the Great Victoria Desert in Australia.

Because of the low rainfall, the soils of subtropical deserts are shallow, virtually devoid of organic matter, and neutral in pH. Whereas sagebrush dominates the cold deserts of the Great Basin, creosote bush (Larrea tridentata) dominates in the subtropical deserts of the Americas. Moister sites support a profusion of succulent cacti, shrubs, and small trees, such as mesquite and paloverde (Cercidium microphyllum). Most subtropical deserts receive summer rainfall. After summer rains, many herbaceous plants sprout from dormant seeds, grow quickly, and reproduce before the soils dry out again. Few plants in subtropical deserts are frost-tolerant. Species diversity is usually much higher than in temperate arid lands.