2.2 Psychological Factors in Psychological Disorders

Both of the Beale women had idiosyncratic ideas and inclinations. For instance, Little Edie, in talking about World War II, expressed an unusual view about who should be soldiers and sent off to fight a war—people who are not physically healthy and hardy. With such people as soldiers, she claimed, the war would be over sooner (Maysles, 2006). In addition, Big Edie was known to command Little Edie to change her attire, repeatedly, up to 10 times each day (Maysles, 2006). Psychological factors, such as learning, can help to account for people’s beliefs and behavior. Could aspects of Big Edie’s and Little Edie’s views and lifestyle have been learned? And how might their emotions—such as Big Edie’s fear of being alone or Little Edie’s resentment of her mother’s control—influence their thoughts and behavior? Let’s examine the role that previous learning, mental processes and contents, and emotions can play in psychological disorders.

Behavior and Learning

As we saw in Chapter 1, psychological disorders involve distress, impaired functioning, and/or risk of harm. These three elements can be expressed in behaviors, such as occurs when people disrupt their daily lives in order to avoid feared stimuli or when they drink too much alcohol to cope with life’s ups and downs. Many behaviors related to psychological disorders can be learned. As we shall see, some psychological disorders can be explained, at least partly, as a consequence of one of three types of learning: classical conditioning, operant conditioning, and observational learning.

Classical Conditioning

Classical conditioning A type of learning that occurs when two stimuli are paired so that a neutral stimulus becomes associated with another stimulus that elicits a reflexive behavior; also referred to as Pavlovian conditioning.

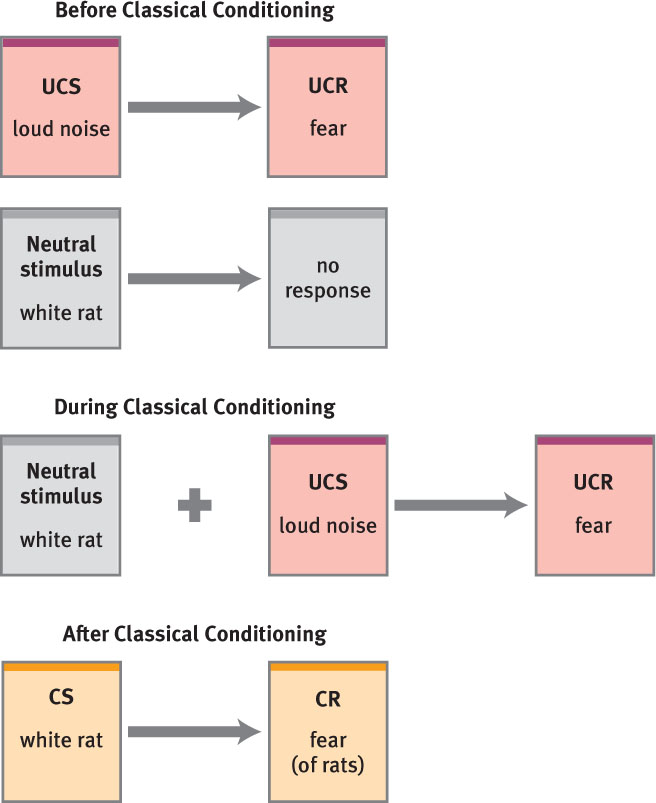

In a landmark study of an 11-month-old infant, known as “Little Albert,” John B. Watson and Rosalie Rayner (1920) demonstrated how to produce a phobia. The researchers conditioned Little Albert to be afraid of white rats, using the basic procedure that Pavlov used when he conditioned his dogs (see Chapter 1), except in this case the reflexive behavior was related to fear rather than salivation. To do this, they made a very loud sound immediately after a white rat (which was used as the neutral stimulus) moved into the child’s view; they repeated this procedure several times. Whenever Little Albert subsequently saw a white rat, he would cry or exhibit other signs of fear. The process that generated Little Albert’s fear of white rats is called classical conditioning—a type of learning that occurs when two stimuli are paired so that a neutral stimulus becomes associated with another stimulus that elicits a reflexive behavior; classical conditioning is also referred to (less commonly) as Pavlovian conditioning. By experiencing pairings of the two stimuli (the white rat and the loud noise in the case of Little Albert), the person comes to respond to the neutral stimulus alone (the white rat) in the same way that he or she had responded to the stimulus that elicited the reflexive behavior (the loud noise).

Unconditioned stimulus (UCS) A stimulus that reflexively elicits a behavior.

How, specifically, does classical conditioning occur? Using the lingo of psychologists, the stimulus that reflexively elicits a behavior is called the unconditioned stimulus (UCS), because it elicits the behavior without prior conditioning. In the case of Little Albert, the loud noise was the UCS, and the behavior it reflexively elicited was a startle response associated with fear. Such a reflexive behavior is called an unconditioned response (UCR). The neutral stimulus that, when paired with the UCS, comes to elicit the reflexive behavior is called the conditioned stimulus (CS). It is called the conditioned stimulus because its ability to elicit the response is conditional on its being paired with a UCS. In Little Albert’s case, the CS was the white rat. The conditioned response (CR) is the response that comes to be elicited by the previously neutral stimulus (the CR is basically the same behavior as the UCR, but the behavior is elicited by the CS). In Little Albert’s case, the CR was the startle response to the rat alone (and ensuing fear-related behaviors, such as crying and trying to avoid the rat). The process of classical conditioning is illustrated in Figure 2.7.

Unconditioned response (UCR) A behavior that is reflexively elicited by a stimulus.

Conditioned stimulus (CS) A neutral stimulus that, when paired with an unconditioned stimulus, comes to elicit the reflexive behavior.

42

Conditioned response (CR) A response that comes to be elicited by the previously neutral stimulus that has become a conditioned stimulus.

Although various reflexive behaviors, such as salivation, can be classically conditioned (Pavlov, 1927), the ones most important for understanding psychopathology are those related to emotional responses such as fear and arousal (Davey, 1987; Schafe & LeDoux, 2004). When emotions and emotion-related behaviors are classically conditioned, they are referred to as conditioned emotional responses. People who have the personality characteristic of being generally emotionally reactive—referred to as being high in neuroticism—are more likely to develop conditioned emotional responses than are people who do not have this personality characteristic (Bienvenu et al., 2001).

Conditioned emotional responses Emotions and emotion-related behaviors that are classically conditioned.

Stimulus generalization The process whereby responses come to be elicited by stimuli that are similar to the conditioned stimulus.

Conditioned responses can also generalize, so that they are elicited by stimuli that are similar to the conditioned stimulus, a process called stimulus generalization. For instance, Little Albert became afraid not only of white rats but also of other white furry things. He even became afraid of a piece of white cotton! His fear of rats had generalized to similar stimuli.

As we shall see in detail in later chapters, classical conditioning is of interest to those studying psychological disorders because it helps to explain various types of anxiety disorders (particularly phobias, such as Little Albert’s phobia), substance abuse and dependence (Hyman, 2005), and the development of specific types of sexual disorders (Domjan et al., 2004).

Operant Conditioning

Operant conditioning A type of learning in which the likelihood that a behavior will be repeated depends on the consequences associated with the behavior.

Operant conditioning is a type of learning in which the likelihood that a behavior will be repeated depends on the consequences associated with the behavior. Operant conditioning usually involves voluntary behaviors, whereas classical conditioning usually involves reflexive behaviors. With operant conditioning, when a behavior is followed by a positive consequence, the behavior is more likely to be repeated. Consider Big Edie’s behavior of crying out for Little Edie to come back into the room. Little Edie then returns to the room (a positive consequence), making it more likely that Big Edie will cry out for Little Edie to return in the future. When a behavior is followed by a negative consequence, it is less likely to be repeated. For instance, the last time Big Edie left Grey Gardens was in 1968, when she and her daughter went to a party at a friend’s house; upon returning home, the Beale women discovered that thieves had taken $15,000 worth of heirlooms. It seemed to Big Edie that her behavior (leaving the house) was followed by a negative consequence (the theft), and so she never left again.

Psychologist B. F. Skinner showed that operant conditioning can explain a great deal of behavior, including abnormal behavior, and operant conditioning can be used to treat abnormal behaviors (Skinner, 1965). As we shall see throughout this book, operant conditioning contributes to various psychological disorders, such as depression, anxiety disorders, substance abuse disorder, eating disorders, and problems with self-regulation in general. Operant conditioning relies on two types of consequences: reinforcement and punishment; each can be either positive or negative.

Reinforcement

Reinforcement The process by which the consequence of a behavior increases the likelihood of the behavior’s recurrence.

A key element in operant conditioning is reinforcement, the process by which the consequence of a behavior increases the likelihood of the behavior’s recurrence. The consequence—an object or event—that makes a behavior more likely in the future is called a reinforcer. In the case of Big Edie’s fear of being alone, the behavior was Big Edie’s calling out to her daughter to return to her room, and it was followed by a reinforcer: Little Edie’s return to her mother’s side.

43

Positive reinforcement The type of reinforcement that occurs when a desired reinforcer is received after a behavior, which makes the behavior more likely to occur again in the future.

We need to consider two types of reinforcement: positive reinforcement and negative reinforcement. Positive reinforcement occurs when a desired reinforcer is received after the behavior, which makes the behavior more likely to occur again in the future. For instance, when someone takes a drug, the chemical properties of the drug may lead the person to experience a temporarily pleasant state (the reinforcer), which he or she may want to experience again, thus making the person more likely to take the drug again.

Negative reinforcement The type of reinforcement that occurs when an aversive or uncomfortable stimulus is removed after a behavior, which makes that behavior more likely to be produced again in the future.

In contrast, negative reinforcement occurs when an aversive or uncomfortable stimulus is removed after a behavior, which makes that behavior more likely to be repeated in the future; note that negative, in this instance, does not necessarily mean “bad.” For example, suppose that a man has a strong fear—a phobia—of dirt. If his hands get even slightly dirty, he will have the urge to wash them and will be uncomfortable until he does so. The act of washing his hands is negatively reinforced by the consequence of removing his discomfort about the dirt, which makes him more likely to wash his hands again the next time they get a bit dirty. Negative reinforcement is often confused with punishment; as we see next, however, the two are very different.

Punishment

Punishment The process by which an event or object that is the consequence of a behavior decreases the likelihood that the behavior will occur again.

Positive reinforcement and negative reinforcement both increase the probability of a behavior’s recurring. In contrast, punishment is a process by which an event or object that is the consequence of a behavior decreases the likelihood that the behavior will occur again. Just as there are two types of reinforcement, there are two types of punishment: positive punishment and negative punishment. Positive punishment takes place when a behavior is followed by an undesirable consequence, which makes the behavior less likely to recur. In other words, an undesired stimulus is added in response to a behavior. For example, imagine that every time a young boy sings along with a song playing on the radio, his older sister makes fun of him (an undesirable consequence): In the future, he won’t sing as often when she’s around. That boy has experienced positive punishment.

Positive punishment The type of punishment that takes place when a behavior is followed by an undesirable consequence, which makes the behavior less likely to recur.

Negative punishment The type of punishment that takes place when a behavior is followed by the removal of a pleasant or desired event or circumstance, which decreases the probability of that behavior’s recurrence.

Negative punishment occurs when a behavior is followed by the removal of a pleasant or desired event or circumstance, which decreases the probability of that behavior’s recurrence. Negative punishment occurs, for example, when a teenager stays out too late with friends and then her parents take away for a week her access to television (or cell phone, e-mail, use of the car, or something else she likes). Big Edie’s father tried to use negative punishment to modify her behavior: He decreased her monthly allowance, repeatedly reduced her inheritance, and even told her that he was doing this because of her eccentric behavior. His attempts at negative punishment did not work, however, which indicates that the consequence he picked—taking away some money—was not meaningful enough to Big Edie. The four types of operant conditioning are compared in TABLE 2.2.

| Type of conditioning | How it occurs | Result | Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| Positive reinforcement | Desired consequence is produced by behavior. | Increased likelihood of the behavior | A pleasant effect from drug use makes drug use more likely to recur. |

| Negative reinforcement | Undesired event or circumstance is removed after behavior. | Increased likelihood of the behavior | The uncomfortable feeling of having dirty hands is relieved by washing them (which makes such washing more likely to recur). |

| Positive punishment | Undesired consequence is produced by behavior. | Decreased likelihood of the behavior | A sister’s humiliating comment about her brother’s singing along with the radio makes future singing in her presence less likely to recur. |

| Negative punishment | Pleasant event or circumstance is removed after behavior. | Decreased likelihood of the behavior | Removing a television from a teenager’s room after he stays out too late makes staying out too late less likely to recur. |

GETTING THE PICTURE

Design Pics/Superstock

44

Learned helplessness The state of “giving up” that arises when an animal or person is in an aversive situation where it seems that no action can be effective.

Receiving frequent punishments or negative criticisms is associated with depression in some people: Over time, some individuals who experience such aversive events eventually give up trying to avoid or escape them and become depressed. Martin Seligman and his colleagues suggested that this giving up is learned through operant conditioning (Miller & Seligman, 1973, 1975). The process appears analogous to what happens to animals in similar circumstances. Consider a classic study by Overmier and Seligman (1967): When caged dogs were electrically shocked, at first they would respond to the shocks, trying to escape from them by moving to a different part of the cage. But when they could not escape the continued shocks, they eventually stopped responding and simply endured, huddling on the floor. Even after they were put in a new cage in which they could easily avoid the shocks by moving, they remained on the floor. This phenomenon, whether in animals or humans, is called learned helplessness: In an aversive situation where it seems that no action can be effective, the animal or person stops trying to escape (Mikulincer, 1994). Learned helplessness is considered to underlie certain types of depression. For example, sometimes people are emotionally abused—continually criticized, humiliated, and belittled—and no matter how hard they try to be “better” (and so prevent the abuse), the emotional abuse continues. When people in such a situation give up trying, they may become depressed and become vulnerable to a variety of stress-related problems.

Feedback Loops in Understanding Classical Conditioning and Operant Conditioning

Let’s suppose that a student gave a presentation that didn’t go well, and some classmates snickered during one part (social factor). Let’s also suppose that this student had an inherited vulnerability (a neurological factor; Stein & Gelernter, 2010) that increased his or her risk of developing a conditioned emotional response—in this case, to making presentations (Mineka & Zinbarg, 1995). And let’s further suppose that the student developed negative, irrational thoughts about public speaking (psychological factor; Abbott & Rapee, 2004; Antony & Barlow, 2002). The three sorts of factors, fueling each other, can increase the likelihood that the student will develop a social phobia—an intense fear of public humiliation or embarrassment, accompanied by an avoidance of social situations likely to elicit this fear.

45

Observational Learning

Observational learning The process of learning through watching what happens to others; also referred to as modeling.

Not all learning involves directly experiencing the associations that underlie classical and operant conditioning. Observational learning (also referred to as modeling) results from watching what happens to others (social factor; Bandura et al., 1961); from our observations, we learn ways to behave as well as develop expectations about what is likely to occur when we behave the same way (psychological factor). Observational learning is primarily a psychological factor: The key is mental processes (who and what behaviors are paid attention to, how the information is perceived and interpreted, how motivated the individual is to imitate the behavior). However, social factors are also involved, which include who the model is, his or her status, and his or her relationship to the observer. For instance, people who have high status or are attractive are more likely to hold our attention—so we are more likely to model their behavior (Brewer & Wann, 1998).

Through observational learning, children can figure out what types of behavior are acceptable in their family (Thorn & Gilbert, 1998), even if the observed behaviors are maladaptive. For example, when children observe parents managing conflict through violence or by drinking alcohol, they may learn to use such coping strategies themselves. From a young age, Little Edie spent much of her time with her mother, and during the 2 years she was kept out of school, she was with her mother practically day and night. Thus, in her formative years, Little Edie had ample opportunity to watch her mother’s eccentric behavior and may have modeled her own eccentric behavior on that of her mother. Further, observational learning and operant conditioning can work together: When Little Edie modeled her behavior after her mother’s, she was no doubt reinforced by her mother.

Mental Processes and Mental Contents

As noted in Chapter 1, both mental processes and mental contents play important roles in the etiology of psychological disorders. Let’s take a closer look at these two types of contributing factors.

Mental Processes

We all have biases in our mental processes; hearing the same conversation, we can differ in what we pay attention to, how we interpret what we hear, and what we remember. With some psychological disorders, mental processes involved in attention, perception, and memory may be biased in particular ways:

- Attention results in selecting certain stimuli, including those that may be related to a disorder (van den Heuvel et al., 2005). Women with an eating disorder, for instance, are more likely than women without such a disorder to focus their attention on the parts of their bodies they consider “ugly” (Jansen et al., 2005) or on words related to food (Brooks et al., 2011).

- Perception results in registering and identifying specific stimuli, such as spiders or particular facial expressions of emotion (Buhlmann et al., 2006). As one example of bias in perception, depressed people are less likely than nondepressed people to rate neutral or mildly happy faces as “happy” (Surguladze et al., 2004).

- Memory involves storing, retaining, and accessing stored information, including that which is emotionally relevant to a particular disorder (Foa et al., 2000).

46

Consider the disorder illness anxiety disorder, which is marked by a preoccupation with bodily sensations, combined with a belief of having a serious illness despite a lack of medical evidence. People suffering from illness anxiety disorder have a memory bias: They are better able to remember health-related words than non–health-related words (Brown, Kosslyn, et al., 1999), which is not surprising considering that the disorder involves a preoccupation with illness.

Thus, various mental processes can contribute to psychopathology by influencing what people pay attention to, how they perceive various stimuli, and what they remember. In turn, these alterations in mental processes influence the content of people’s thoughts by shifting their awareness of various situations, objects, and stimuli.

Mental Contents

The contents of people’s thoughts can play a role in whether someone develops a psychological disorder. Psychiatrist Aaron Beck (1967) proposed that dysfunctional, maladaptive thoughts are the root cause of psychological problems. These dysfunctional thoughts are cognitive distortions of reality. An example of a dysfunctional belief is a woman’s conviction that she is unlovable—that if her boyfriend really knew her, he couldn’t love her. Cognitive distortions can make a person vulnerable to psychological disorders and are sometimes referred to as cognitive vulnerabilities (Riskind & Alloy, 2006). Beck (1967) also argued that recognizing these false and dysfunctional thoughts and adopting realistic and adaptive thoughts can reduce psychological problems. Cognitive distortions can be a result of maladaptive learning from previous experiences. A man with a classically conditioned fear of rodents, for instance, may come to believe that rodents are dangerous because of the fear and anxiety he experiences when he’s with them. Operant conditioning can also give rise to cognitive distortions. For instance, a child who is repeatedly rejected by her father can grow up to believe that nobody could love her. In this case, the conditioning could have occurred when, every time she tried to hug her father, he turned away. Cognitive distortions and biased mental processes affect each other. Several common cognitive distortions are presented in TABLE 2.3.

| Cognitive distortion | Definition | Example |

|---|---|---|

| All-or-nothing thinking | Seeing things in black and white | You think that if you are not perfect, you are a failure. |

| Overgeneralization | Seeing a single negative event as part of a never-ending pattern of such events | While having a bad day, you predict that subsequent days will also be bad. |

| Mental filter | Focusing too strongly on negative qualities or events, to the exclusion of the other qualities or events | Although your overall appearance is fine, you focus persistently on the bad haircut you recently had. |

| Disqualifying the positive | Not recognizing or accepting positive experiences or events, thus emphasizing the negative | After giving a good presentation, you discount the positive feedback you received and focus only on what you didn’t like about your performance. |

| Jumping to conclusions | Making an unsubstantiated negative interpretation of events | Although there is no evidence for your inference, you assume that your boss didn’t like your presentation. |

| Personalization | Seeing yourself as the cause of a negative event when in fact you were not actually responsible | When your parents fight about finances, you think their problems are somehow your fault, despite the fact that their financial troubles weren’t caused by you. |

| Source: Copyright © 1980 by David D. Burns, M.D. Reprinted by permission of HarperCollins Publishers, William Morrow. For more information see the Permissions section. | ||

Cognitive distortions Dysfunctional, maladaptive thoughts that are not accurate reflections of reality and contribute to psychological disorders.

47

Mental health professionals need to keep in mind, however, cultural factors that may contribute to what appear to be maladaptive cognitive distortions but in fact reflect appropriate social behavior in a patient’s culture. For instance, some cultures, such as that of Japan, have a social norm of responding to a compliment with a self--deprecating statement. It is only through careful evaluation that a clinician can discern whether such self-deprecating behavior reflects a patient’s attempt to show good manners or his or her core maladaptive dysfunctional beliefs about self.

Emotion

Emotion A short-lived experience evoked by a stimulus that produces a mental response, a typical behavior, and a positive or negative subjective feeling.

Affect An emotion that is associated with a particular idea or behavior, similar to an attitude.

Many psychological disorders include problems that involve emotions: not feeling or expressing enough emotions (such as showing no response to a situation where others would be joyous or sad), having emotions that are inappropriate or inappropriately excessive for the situation (such as feeling sad to the point of crying for no apparent reason), or having emotions that are difficult to regulate (such as overwhelming panic) (Aldao & Nolen-Hoeksema, 2010; American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Inappropriate affect An expression of emotion that is not appropriate to what a person is saying or to the situation.

But what, specifically, are emotions? To psychologists, an emotion is a short-lived experience evoked by a stimulus that produces a mental response, a typical behavior, and a positive or negative subjective feeling. The stimulus that initiates an emotion could be physical: It can be a kiss, the positive comments on an essay you get back from a professor, or the sounds of a tune you listen to on your computer. Alternatively, the stimulus can occur only in the mind, such as remembering a sad occasion or tune or imagining your perfect mate.

Flat affect A lack of, or considerably diminished, emotional expression, such as occurs when someone speaks robotically and shows little facial expression.

Labile affect Affect that changes inappropriately rapidly.

Mental health clinicians and researchers sometimes use the word affect to refer to an emotion that is associated with a particular idea or behavior, similar to an attitude. Affect is also used to describe how emotion is expressed, as when noting that a patient has inappropriate affect—the patient’s expression of emotion is not appropriate to what he or she is saying or to the situation. An example is a person laughing at a funeral or talking about a happy event while looking sad or angry. Flat affect is a lack of, or considerably diminished, emotional expression, such as occurs when someone speaks robotically and shows little facial expression. People with some psychological disorders, such as schizophrenia, frequently display inappropriate or flat affect. Other people may exhibit labile affect, a pattern in which affect changes very rapidly—too rapidly. Labile affect may indicate a psychological disorder; for instance, some people with depression may quickly shift emotions from sad to angry or irritable.

In the film Grey Gardens, Little Edie and her mother often displayed inappropriate affect, and Little Edie’s emotions were sometimes labile, rapidly changing from anger to happy excitement to relative calm. For instance, at one point, Big Edie recounts that when Little Edie had moved to New York City, Big Edie wanted Mr. Beale to return to Grey Gardens. Little Edie immediately started yelling, “You’re making me very angry!” (Maysles & Maysles, 1976), even though one moment before she had been relatively calm, and they were talking about events that had transpired over 20 years earlier.

Mood A persistent emotion that is not attached to a stimulus; it exists in the background and influences mental processes, mental contents, and behavior.

A mood is a persistent emotion that is not attached to a stimulus. A mood lurks in the background and influences mental processes, mental contents, and behavior. For example, when you wake up “on the wrong side of the bed” for no apparent reason and feel grumpy all day, you are experiencing a type of bad mood. Some psychological disorders, such as depression, involve disturbances in mood.

Emotions and Behavior

Emotions and behavior dynamically interact. On the one hand, emotion can change behavior. People are more likely to participate in activities and behave in ways that are consistent with their emotions (Bower & Forgas, 2000). For instance, when people are sad, they tend to hunch their shoulders and listen to slow music rather than upbeat music; when people are afraid, they tend to freeze, like a deer caught in the headlights; and when people are depressed, they often don’t have the inclination or energy to see friends, which can lead to social isolation. On the other hand, a change in behavior can lead to a change in emotion. When people who are depressed make an effort to see friends or engage in other activities that they used to enjoy, they often become less depressed (Jacobson et al., 2001).

48

Emotions, Mental Processes, and Mental Contents

Emotions affect behavior as well as mental processes and mental contents. In fact, emotions and moods contribute to biases in attention, perception, and memory (Demenescu et al., 2010; MacKay & Ahmetzanov, 2005; Mogg & Bradley, 2005; Yovel & Mineka, 2005). For example, when feeling down, people are more likely to see the world through “depressed” lenses, to have a negative or pessimistic slant in general; not only will they find it easier to remember past periods of sadness, but they will also tend to view the future as hopeless; they will see more reasons to be sad than will people who aren’t down (Lewis & Critchley, 2003).

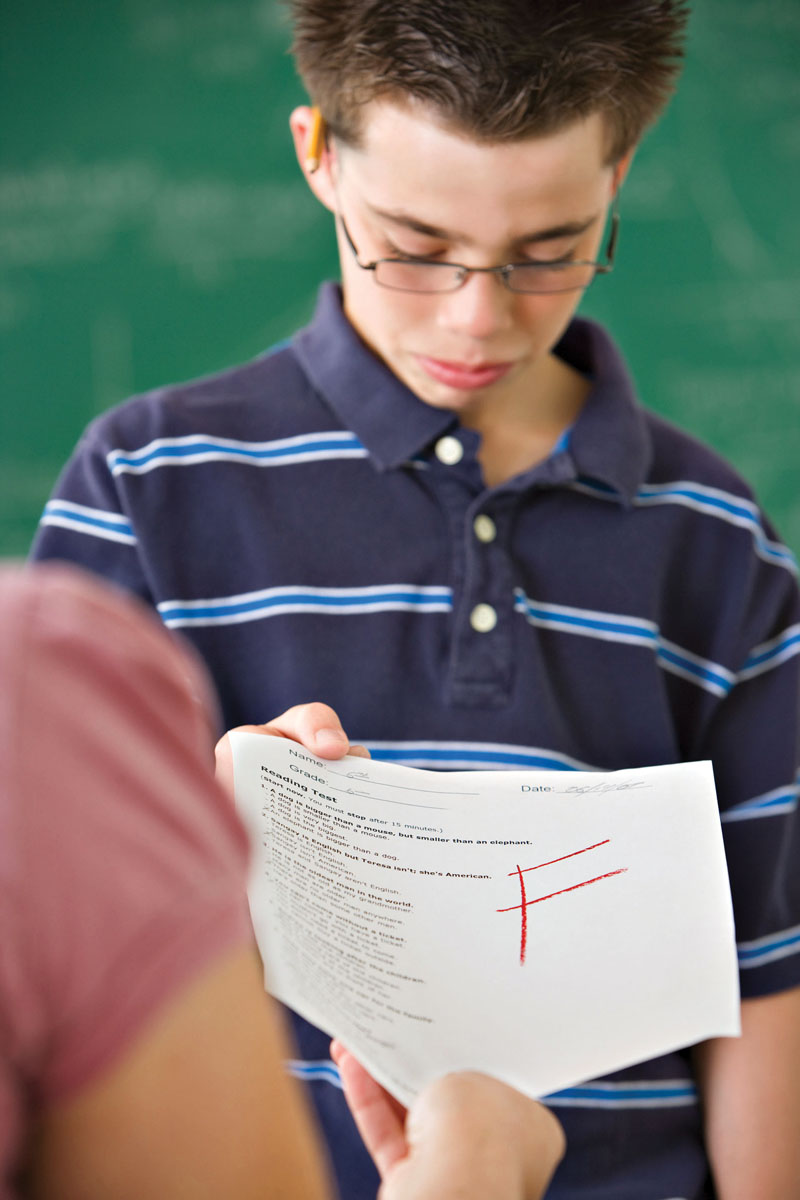

The causality also works in the other direction: Mental processes can affect emotions. For example, emotions are affected by attributions. That is, we all regularly try to understand why events in our lives occur, and thus make attributions, assigning causes for particular occurrences. A person’s mood can be affected by the attributions he or she makes. For instance, college students who tend to attribute negative events to general, enduring negative qualities about themselves (“I am stupid”) are more likely to become depressed after a negative event (such as getting a bad grade) (Metalsky et al., 1993).

Emotional Regulation and Psychological Disorders

Difficulty in regulating emotions and related thoughts and behaviors can lead to three types of problems (Cicchetti & Toth, 1991; Weisz et al., 1997):

- Externalizing problems are characterized by too little control of emotion and related behaviors, such as aggression, and by disruptive behavior. They are called externalizing problems because their primary effects are on others and/or their environment; these problems are usually observable to others.

- Internalizing problems are characterized by negative internal experiences, such as anxiety, social withdrawal, and depression. Internalizing problems are so named because their primary effect is on the troubled individual rather than on others; such problems are generally less observable to others.

- Other problems include emotional or behavioral problems that do not fit into these categories. This “other” category includes eating disorders and learning disorders (Achenbach et al., 1987; Kazdin & Weisz, 1998).

Significant difficulty in regulating emotions can begin in childhood and last through adulthood, forming the basis for some disorders.

Neurological Bases of Emotion

Emotion is a psychological response, but it is also a neurological response. We can learn much about the psychological aspects of emotion by considering how it arises from brain function. For example, research by Richard Davidson and colleagues, conducted largely by measuring the brain’s electrical activity, have demonstrated that there are two general types of human emotions, approach emotions and withdrawal emotions, each relying on its own system in the brain. Approach emotions are positive emotions, such as love and happiness, and tend to activate the left frontal lobe more than the right. Withdrawal emotions are negative emotions, such as fear and sadness, and tend to activate the right frontal lobe more than the left (Davidson, 1992a, 1992b, 1993, 1998, 2002; Davidson et al., 2000; Lang, 1995). Researchers have also found that people who generally have more activation in the left frontal lobe tend to be more optimistic than people who generally have more activation in the right. This is important because depression has been associated with relatively less activity in the left frontal lobe (Davidson, 1993, 1994, 1998; Davidson et al., 1999). As a result of genetics, learning, or (most likely) some combination of the two, some people are temperamentally more likely to experience positive (approach) emotions, whereas others are more likely to experience negative (withdrawal) emotions (Fox et al., 2005; Rettew & McKee, 2005).

49

Temperament

Temperament The aspects of personality that reflect a person’s typical emotional state and emotional reactivity (including the speed and strength of reactions to stimuli).

Temperament is closely related to emotion: Temperament refers to the aspects of personality that reflect a person’s typical emotional state and emotional reactivity (including the speed and strength of reactions to stimuli). Temperament is in large part innate, and it influences behavior in early childhood and even in infancy. Temperament is of interest in the study of psychological disorders for two reasons (Nigg, 2006a): First, specific types of temperament may make a person especially vulnerable to certain psychological disorders, even at an early age. For instance, people who are temperamentally more emotionally reactive are more likely to develop psychological disorders related to high levels of anxiety. Second, it is possible that in some cases a psychological disorder is simply an extreme form of a normal variation in temperament. For instance, some researchers argue that social phobia is on a continuum with shyness but is an extreme form of it; shyness involves withdrawal emotions and lack of sociability, and is viewed as a temperament (Schneider et al., 2002).

The Beale women had unusually reactive temperaments—they reacted strongly to stimuli. One or the other of them would respond to a neutral or offhand remark with emotion that was out of proportion: hot anger, bubbling joy, or snapping irritability. It’s not a coincidence that mother and daughter seemed similar in this respect. Much evidence indicates that genes contribute strongly to temperament (Gillespie et al., 2003); in fact, some researchers report that genes account for about half of the variability in temperament (Oniszcenko et al., 2003). Researchers have associated some aspects of temperament to specific genes, such as genes that affect receptors for the neurotransmitter dopamine and a gene involved in serotonin production, and have shown that these genes can influence depression and problems controlling impulses (Nomura et al., 2006; Propper & Moore, 2006). Genes that affect dopamine receptors have also been shown to influence emotional reactivity (Oniszcenko & Dragan, 2005). However, these genes have stronger effects on children raised in harsh family environments; as we stressed earlier, the effects of genes need to be considered within the context of specific environments (Roisman & Fraley, 2006; Saudino, 2005).

C. Robert Cloninger and his colleagues have proposed one particularly influential theory of temperament, which describes temperament in terms of four dimensions—novelty seeking, harm avoidance, reward dependence, and persistence—each of which is associated with a brain system that relies predominantly on a particular neurotransmitter, as shown in TABLE 2.4 (Cloninger, 1987b; Cloninger et al., 1993).

| Temperament | Description | Hypothesized related neurotransmitter | Associated disorder(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Novelty seeking | Searching out novel stimuli and reacting positively to them; high levels can lead to being impulsive, avoiding frustration, and easily getting angry | Dopamine | With a high level, disorders that involve impulsive or aggressive behaviors |

| Harm avoidance | Reacting very negatively to harm and avoiding it whenever possible | Serotonin | With a high level, anxiety disorders |

| Reward dependence | Degree to which past behaviors that have led to desired outcomes in the past are repeated | Norepinephrine | With a low level (in combination with high impulsivity), substance use disorders |

| Persistence | Making continued efforts in the face of frustration when attempting to accomplish something. | Possibly dopamine | With a low level, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder |

In fact, researchers have found associations between genes and these dimensions of temperament (Gillespie et al., 2003; Keltikangas-Järvinen et al., 2006; Rybakowski et al., 2006). The specific results suggest that temperament arises from the joint activity of many different genes.

50

Thinking Like A Clinician

Maya is depressed; she’s often tearful and feels hopeless about the future and helpless to change the negative things in her life. Give specific examples of the ways that types of learning might have influenced her negative expectations of life and led to her current depression. (It’s okay to speculate here, but be specific.) Based on what you have read, how can Maya’s thought patterns and emotions lead to her feeling depressed (or make the depression worse)?