4.2 Research Challenges in Understanding Abnormality

Let’s now examine the hypothesis about the relationship between experiencing a childhood loss and feeling depressed after a breakup in adulthood. How can we use the neuropsychosocial approach to understand why breaking up might lead some people to become depressed?

- We could investigate neurological mechanisms by which early loss, associated with helplessness, might make people more vulnerable to later depression.

- We could investigate psychological effects resulting from early loss, such as problems with emotional regulation.

- We could investigate social mechanisms, such as how economic hardships arising from the early loss created a higher baseline of response to daily stress.

- And, crucially, we could propose ways in which these possible factors might interact with one another. For example, perhaps daily financial stress not only increases the degree of worrying about money but such worrying in turn changes neurological functioning as well as social functioning (as preoccupying financial worries alter social interactions).

Whatever type of factors researchers investigate, each type comes with its own challenges, which affect the way a study is undertaken and which limit the conclusions that can be drawn from a study’s results (Slavich et al., 2011). In what follows, we examine the major types of challenges to research on the nature and causes of abnormality from the neuropsychosocial perspective.

Challenges in Researching Neurological Factors

DSM-5 does not generally consider neurological factors when assigning diagnoses, but many researchers are exploring the possible role of neurological factors in causing psychological disorders. In fact, current findings about neurological factors are coming to play an increasingly large role in treatment.

With the exception of genetics, almost all techniques that assess neurological factors identify abnormalities in the structure or function of the brain. This assessment is done directly (e.g., with neuroimaging) or indirectly (e.g., with neuropsychological testing or measurements of the level of stress hormones in the bloodstream). Such abnormalities are associated (correlated) with specific disorders or symptoms. For instance, people with schizophrenia have larger-than-normal ventricles (the fluid-containing cavities in the brain), and other areas of the brain are correspondingly smaller (Vita et al., 2006). Like all other correlational studies, the studies that revealed the enlarged ventricles cannot establish causation; for example, this finding does not specify whether schizophrenia arises because of the effects of this brain abnormality, whether schizophrenia creates these abnormalities, or whether some third variable is responsible for the brain abnormality and for the mental disorder. Another limitation of research using neuroimaging is that we do not yet have a complete understanding of what different parts of the brain do. Thus, researchers cannot be sure about the implications of abnormalities in the structure or the functioning of any specific brain structure.

Nevertheless, the outlook is encouraging. Researchers do know a considerable amount about what specific parts of the brain do, and they are learning more every day. Also, they can use other techniques in combination with neuroimaging to learn which brain areas may play a role in causing or contributing to certain disorders. We will have more to say about neuroimaging research in subsequent chapters.

101

Challenges in Researching Psychological Factors

Scientists who study neurological factors examine the difficulties with the biological mechanisms that process information or that give rise to emotion. In contrast, scientists who study psychological factors examine specific mental contents, mental processes, behaviors, or emotions. Information about psychological factors typically is obtained from patients’ self-reports, from reports by others close to patients, or from direct observations.

Biases in Mental Processes That Affect Assessment

Assessing mental contents, emotions, and behaviors via self-report or report by others can yield inaccurate information because of biases in what people pay attention to, remember, and report. Sometimes beliefs, expectations, or habits bias how participants respond, consciously or unconsciously. For instance, people who have anxiety disorders are more likely than others to be extremely attentive to stimuli that might be perceived as a threat (Cloitre et al., 1994; Mogg et al., 2000). In contrast, people with depression do not have this particular bias but tend to be biased in what they recall; they are more likely than people who are not depressed to recall unpleasant events (Watkins, 2002; Wisco & Nolen-Hoecksema, 2009). In fact, researchers have found that people in general are more likely to recall information consistent with their current mood than information that is inconsistent with their current mood (referred to as mood-congruent memory bias; Teasdale, 1983).

Research Challenges with Clinical Interviews

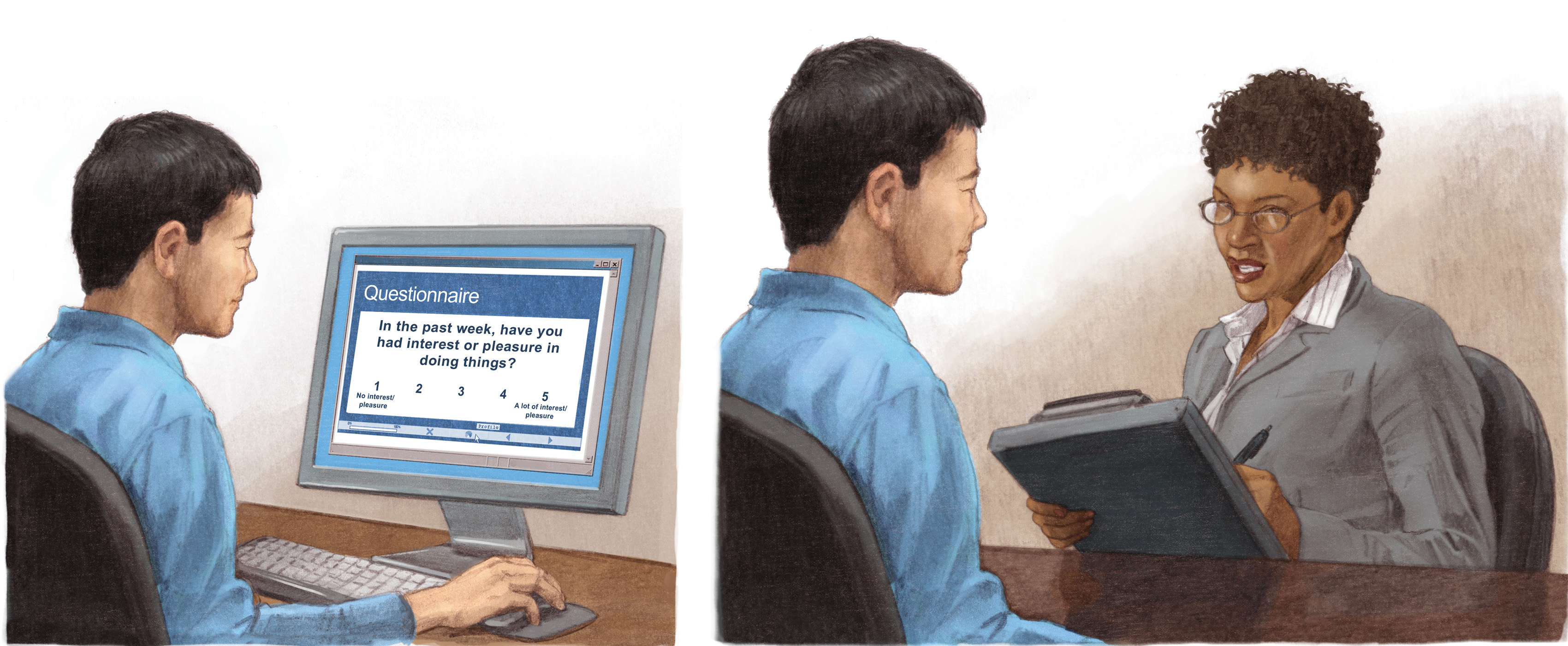

Patients’ responses can be affected by whether they are asked questions by an interviewer or receive them in writing (see Figure 4.3). Consider a study in which participants were asked questions about their symptoms of either OCD or social phobia. When the questions were first asked by a clinician as part of an interview, participants tended not to report certain avoidance-related symptoms that they later did report on a questionnaire. In contrast, when participants completed the questionnaire first, they reported these symptoms both on the questionnaire and in the subsequent interview (Dell’Osso et al., 2002).

Moreover, when interviewing family members or friends about a patient’s behavior, researchers must keep in mind that these people may have their own biases. They may pay more attention to, and so be more likely to remember, particular aspects of a patient’s behavior, and they may have their own views about the causes of the patient’s behavior (Achenbach, 2008; Kirk & Hsieh, 2004). For example, when assessing children, researchers sometimes rely heavily on reports from others, such as parents and teachers; however, these individuals often do not agree on the nature or cause of a child’s problems (De Los Reyes & Kazdin, 2004).

Research Challenges with Questionnaires

In psychopathology research, administering questionnaires is a relatively inexpensive way to collect a lot of data quickly. However, questionnaires must be designed carefully in order to avoid various biases. For example, one sort of bias arises when a range of alternative responses are presented. Some questionnaires provide only two choices in response to an item (“yes” or “no”), whereas other questionnaires give participants more than two choices (such as, “all the time,” “frequently,” “sometimes,” “infrequently,” or “never”). With more choices come more opportunities for bias: Twice a week might be interpreted as frequent by one person and infrequent by another. To reduce the effects of such bias, some questionnaires—such as the Posttraumatic Diagnostic Scale (Foa et al., 1997)—define the frequency choices in terms of specific numerical values (such as having “frequently” defined as three times a week).

102

In addition, the range of values on a scale is important. For example, consider the findings obtained when people were asked to rate how successful they have been in life. When asked to respond on a rating scale with numbers from −5 to +5, like this:

34% reported having been highly successful in life. When asked to respond on a scale with numbers from 0 to 10, like this:

only 13% reported having been highly successful in life (Schwarz et al., 1991).

Response bias The tendency to respond in a particular way, regardless of what is being asked by the question.

Response bias is another problem to avoid when designing questionnaires. Response bias refers to a tendency to respond in a particular way, regardless of what is being asked by the questions. For instance, some people, and members of some cultures in general, are more likely to check “agree” than “disagree,” regardless of the content of the statement (Javeline, 1999; Welkenhuysen-Gybels et al., 2003). This type of response bias, called acquiescence, can be reduced by wording half the items negatively. Thus, if you were interested in assessing self-reported shyness in a questionnaire, you might include both the item “I often feel shy when meeting new people” and the item “I don’t usually feel shy when meeting new people,” which is simply a negative rewording of the first item.

Social desirability A bias toward answering questions in a way that respondents think makes them appear socially desirable, even if the responses are not true.

Another type of response bias is social desirability: answering questions in a way that the respondent thinks makes him or her look good in a way that he or she thinks is socially desirable, even if the answer is not true. For instance, some people might not agree with the statement “It is better to be honest, even if others don’t like you for it.” However, they may think that they should agree and respond accordingly. In contrast to a social desirability bias, some people answer questions in a way that they think makes them “look bad” or look worse than they actually are. To compensate for these biases, many personality inventories have a scale that assesses the participant’s tendency to answer in a socially desirable or falsely symptomatic manner. This scale is then used to adjust (or, in the language of testing, to “correct”) the scores on the part of the inventory that measures traits.

Challenges in Researching Social Factors

Information obtained from and about people always has a context. For research on psychopathology, a crucial part of the context is defined by other people. Social factors arise from and characterize the setting (such as a home, hospital, outpatient clinic, or university), the people administering the study, and the cultural context writ large. Challenges to conducting research on social factors that affect psychopathology include the ways that the presence or behavior of the investigator and the beliefs and assumptions of a particular culture can influence participants’ responses.

103

Investigator-Influenced Biases

Like psychological factors, social factors are often assessed by self-report (such as patient’s reports of financial problems), reports by others (such as family members’ descriptions of family interactions or of a patient’s behavior), and direct observation. Along with the biases we’ve already mentioned, the social interaction between investigator and participant can affect these kinds of data.

Experimenter Expectancy Effects

Experimenter expectancy effect The investigator’s intentionally or unintentionally treating participants in ways that encourage particular types of responses.

Experimenter expectancy effect refers to the investigator’s intentionally or unintentionally treating participants in ways that encourage particular types of responses. The experimenter expectancy effect is slightly misnamed: It applies not only to experiments but to all psychological investigations in which an investigator interacts with participants. For instance, suppose that you are interviewing patients about their symptoms. It’s possible that you might ask certain types of questions (such as about their social lives) with a particular tone of voice or facial expression, unintentionally suggesting the type of answer you hope to hear. Participants might, consciously or unconsciously, try to respond as they think you would like, perhaps exaggerating certain symptoms a bit. Such a social interaction can undermine the validity of the study.

Double-blind design A research design in which neither the participant nor the investigator’s assistant knows the group to which specific participants have been assigned or the predicted results of the study.

To minimize the likelihood of experimenter expectancy effects, researchers often use a double-blind design: Neither the participants nor the investigator’s assistant (who has contact with the participants) know the group to which each participant has been assigned or the predicted results of the study. Moreover, instructions given to participants or questions asked of them are standardized, so that all participants are treated in the same way.

Reactivity

Reactivity A behavior change that occurs when one becomes aware of being observed.

Have you ever noticed that you were being watched while you were doing something? Did you find that you behaved somewhat differently simply because you knew that you were being observed? If so, then you have experienced reactivity—a behavior change that occurs when one becomes aware of being observed. When participants in a study know that they are observed, they may subtly (or not so subtly) change their behavior, leading the study to have results that may not be valid. One way to counter such an effect is to use hidden cameras, but this may raise ethical issues—many people (rightfully) object to being “spied on.”

Cultural Differences in Evaluating Symptoms

Some researchers compare and contrast a given disorder in different cultures, trying to distinguish universal symptoms from symptoms that are found only in certain cultures. But assessing psychological and social factors in other cultures can be challenging. For one thing, many words and concepts do not have exact equivalents across languages, making full translation impossible. And even when two cultures share a language, the meaning of a word may be different in each culture. For example, when a comprehensive set of interview questions was translated into Spanish and administered to residents of Puerto Rico and Mexico, 67% of the questions had to be changed because the meanings of some of the Spanish words were understood differently by the two populations (Kihlstrom, 2002b).

104

In addition, members of different cultures may have different response biases. For instance, the Japanese consider it rude to say, “No,” so we must be suspect of results from Japanese surveys that require Yes/No responses. Sampling biases may also vary across cultures. For example, women may be underrepresented in samples from certain countries in the Middle East.

Thinking Like A Clinician

Suppose you are reading about a psychologist who conducts research that is aimed at better understanding people who have pyromania—the intense urge to start fires—and why they start fires. The participants can come from two groups: those who’ve been arrested for arson and those who have interacted in a chat room for people with urges to start fires. To collect data, the researcher could either have participants complete an anonymous survey online or arrange to interview them over the phone. What biases might uniquely affect each method, and what biases might affect both? How could a researcher try to minimize these biases? Suppose some participants agree to have their brains scanned while they imagined lighting fires: How might an investigator use such neuroimaging information?