5.1 Depressive Disorders

Most people who read Jamison’s description of her senior year in high school would think that she was depressed during that time. But what, exactly, does it mean to say that someone is depressed? The diagnoses of depressive disorders are based on the presence of building blocks, which are episodes of specific types of abnormal mood. For depressive disorders, the building block that leads to a diagnosis is a major depressive episode; people whose symptoms have met the criteria for a major depressive episode (see TABLE 5.2) are diagnosed with major depressive disorder.

|

| Reprinted with permission from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, (Copyright ©2013). American Psychiatric Association. All Rights Reserved. |

Major Depressive Episode

Major depressive episode (MDE) A mood episode characterized by severe depression that lasts at least 2 weeks.

A Major depressive episode (MDE) is characterized by severe depression that lasts at least 2 weeks. MDE is not itself a diagnosis but a set of symptoms that support making a diagnosis. Mood (which is a type of affect) is not the only symptom of a major depressive episode. As noted in TABLE 5.2, specific types of behavior and cognition also characterize depression.

Affect: The Mood Symptoms of Depression

Anhedonia A difficulty or inability to experience pleasure.

During an MDE, a person can feel unremitting sadness, hopelessness, or numbness. Some people also suffer from a loss of pleasure, referred to as Anhedonia, a state in which activities and intellectual pursuits that were once enjoyable no longer are, or at least are not nearly as enjoyable as they once were. Someone who liked to go to the movies, for instance, may no longer find it so interesting or fun and may feel that it is not worth the effort. Anhedonia can thus lead to social withdrawal. Other mood-related symptoms of depression include weepiness—crying at the drop of a hat or for no apparent reason—and decreased sexual interest or desire.

Behavioral and Physical Symptoms of Depression

Psychomotor agitation An inability to sit still, evidenced by pacing, hand wringing, or rubbing or pulling the skin, clothes, or other objects.

People who are depressed make more negative comments, make less eye contact, are less responsive, speak more softly, and speak in shorter sentences than people who are not depressed (Gotlib & Robinson, 1982; Segrin & Abramson, 1994). Depression may also be evident behaviorally in one of two ways: psychomotor agitation or psychomotor retardation. Psychomotor agitation is an inability to sit still, evidenced by pacing, hand wringing, or rubbing or pulling the skin, clothes, or other objects. In contrast, Psychomotor retardation is a slowing of motor functions indicated by slowed bodily movements and speech (in particular, longer pauses in answering) and lower volume, variety, or amount of speech. Psychomotor retardation, along with changes in appetite, weight, and sleep, are classified as vegetative signs of depression. Sleep changes can involve insomnia or, less commonly, Hypersomnia, which is sleeping more hours each day than normal. In addition, people who are depressed may feel less energetic than usual or feel tired or fatigued even when they don’t physically exert themselves.

Psychomotor retardation A slowing of motor functions indicated by slowed bodily movements and speech and lower volume, variety, or amount of speech.

Hypersomnia Sleeping more hours each day than normal.

117

Cognitive Symptoms of Depression

When in the grip of depression, people often feel worthless or guilt-ridden, may evaluate themselves negatively for no objective reason, and tend to ruminate over their past failings (which they may exaggerate). They may misinterpret ambiguous statements made by other people as evidence of their worthlessness. For instance, a depressed man, Tyrone, might hear a colleague’s question “How are you?” as an indication that he is incompetent and infer that the colleague is asking the question because Tyrone’s incompetence is so obvious. Depressed patients can also feel unwarranted responsibility for negative events, to the point of having delusions that revolve around a strong sense of guilt, deserved punishment, worthlessness, or personal responsibility for problems in the world. They blame themselves for their depression and for the fact that they cannot function well. During a depressive episode, people may also report difficulty thinking, remembering, concentrating, and making decisions, as author William Styron describes in Case 5.1. To others, the depressed person may appear distracted.

CASE 5.1 • FROM THE INSIDE: Major Depressive Episode

Another experience of depression was captured by the writer William Styron in his memoir, Darkness Visible:

In depression this faith in deliverance, in ultimate restoration, is absent. The pain is unrelenting, and what makes the condition intolerable is the foreknowledge that no remedy will come—not in a day, an hour, a month, or a minute. If there is mild relief, one knows that it is only temporary; more pain will follow. It is hopelessness even more than pain that crushes the soul. So the decision making of daily life involves not, as in normal affairs, shifting from one annoying situation to another less annoying—or from discomfort to relative comfort, or from boredom to activity—but moving from pain to pain. One does not abandon, even briefly, one’s bed of nails, but is attached to it wherever one goes.

(Styron, 1990, p. 62)

Note, however, that depression is heterogeneous, which means that people with depression experience these symptoms in different combinations. No single set of symptoms is shared by all people with depression (Hasler et al., 2004). Moreover, researchers distinguish two types of depression: Whereas with typical depression, people develop insomnia, lose weight, and their poor mood persists throughout the day, with atypical depression, people sleep more, gain weight, and their mood brightens in response to positive events.

118

Prodrome Early symptoms of a disorder.

The symptoms of MDE develop over days and weeks. A Prodrome is the early symptoms of a disorder or an episode, and the prodrome of an MDE may include anxiety or mild depressive symptoms that last weeks to months before fully emerging as a major depressive episode. An untreated MDE typically lasts approximately 4 months or longer (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). The more severe the depression, the longer the episode is likely to last (Melartin et al., 2004). About two thirds of people who have an MDE eventually recover from the episode completely and return to their previous level of functioning—referred to as the Premorbid level of functioning. About 20–30% of people who have an MDE find that their symptoms lessen over time, to the point where they no longer meet the criteria for an MDE, but their depression doesn’t completely resolve and may persist for years.

Premorbid Referring to the period of time prior to a patient’s illness.

What distinguishes depression from simply “having the blues”? One distinguishing feature is the number of symptoms. People who are sad or blue generally have fewer than five of the symptoms listed in the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for a major depressive episode (see TABLE 5.2). In addition, someone who is truly depressed has severe symptoms for a relatively long period of time and is unable to function effectively at home, school, or work.

One possible exception is grief—which can mimic most or even all symptoms of depression. In the previous edition of DSM (DSM-IV), people were not considered to have an MDE if the symptoms could have occurred because of the loss of a loved one; this was called the “bereavement exclusion.” With this exclusion, if someone has symptoms of depression within a couple months after the loss of a loved one and isn’t suffering from significantly impaired functioning, thoughts of suicide, or psychotic behavior, that person shouldn’t be considered to have an MDE.

However, in DSM-5 this exception has been removed, and that change is controversial. On the one hand, those who support removing this exception claim that bereavement-related depression, unlike grief, is similar to an MDE unrelated to bereavement (Kendler et al., 2008; Lamb et al., 2010; Zisook et al., 2007). They claim that the hallmark of grief is waves of loss and emptiness and thoughts of the deceased, whereas the hallmark of depression is persistent and sad or depressed thoughts that are not solely focused on one thing. They stress that, left untreated, depression related to bereavement can be as harmful and debilitating as other forms of depression.

On the other hand, removing the bereavement exclusion may lead to overdiagnosis of—and rush to treat with medication or psychotherapy—people who are merely grieving (Wakefield & First, 2012). Training and careful evaluation are required to distinguish normal grieving from an MDE (Pies, 2013), but not every clinician will have that training nor the time to make the careful evaluation. This is particularly likely for family doctors or internists, who are at the forefront of diagnosing and treating depression (Katz, 2012; Montano, 1994).

Major Depressive Disorder

Major depressive disorder (MDD) A mood disorder marked by five or more symptoms of an MDE lasting more than 2 weeks.

According to DSM-5, once someone’s symptoms meet the criteria for a major depressive episode, he or she is diagnosed as having Major depressive disorder (MDD)—five or more symptoms of an MDE lasting more than 2 weeks. Moreover, the clinician specifies whether mixed features characterize the mood episode—whether the person has some symptoms of mania or hypomania (to be discussed later) but not enough of these sorts of symptoms to meet the criteria for those mood episodes. The mental health professional also specifies whether this is the first or a recurrent episode. Thus, for example, after Kay Jamison had her first major depressive episode, she had the diagnosis of MDD, single episode. More than half of those who have had a single depressive episode go on to have at least one additional episode, noted as recurrent depression. Some people have increasingly frequent episodes over time, others have clusters of episodes, and still others have isolated depressive episodes followed by several years without symptoms (American Psychiatric Association, 2000; McGrath et al., 2006). DSM-5 allows mental health professionals to rate the patient’s depression as mild, moderate, or severe.

119

Major depressive disorder leads to lowered productivity at work—both from missing days on the job and from presenteeism, being present but being less productive than normal (Adler et al., 2006; Druss et al., 2001; Stewart et al., 2003). For people whose jobs require high levels of cognitive effort, even mild memory or attentional difficulties may disrupt their ability to function adequately at work.

Phototherapy Treatment for depression that uses full-spectrum lights; also called light-box therapy.

Sometimes recurrent depression follows a seasonal pattern, occurring at a particular time of year. Previously referred to as seasonal affective disorder, this variant of MDD commonly is characterized by recurrent depressive episodes, hypersomnia, increased appetite (particularly for carbohydrates), weight gain, and irritability. These symptoms usually begin in autumn and continue through the winter months. The symptoms either disappear or are much less severe in the summer. Surveys find that approximately 4–6% of the general population experiences a winter depression, and the average age of onset is 23 years. The disorder is four times more common in women than in men (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Winter depression often can be treated effectively with Phototherapy (also called light-box therapy), in which full-spectrum lights are used as a treatment (Golden et al., 2005).

MDD is common in the United States: Up to 20% of Americans will experience it at some point during their lives (Kessler et al., 2003). The documented rate of depression in the United States is increasing (Lewinsohn et al., 1993; Rhode et al., 2013), perhaps because of increased stressors in modern life or decreased social support; in addition, at least part of this increase may simply reflect higher reporting rates. Depression is currently associated with more than $30 billion of lost productivity among U.S. workers annually (Stewart et al., 2003).

Age cohort A group of people born in a particular range of years.

Evidence also suggests that the risk of developing depression is increasing for each Age cohort, a group of people born in a particular range of years. The risk of developing depression is higher among people born more recently than those born during earlier parts of the previous century. In addition, if someone born more recently does develop depression, that person probably will first experience it earlier in life than someone in an older cohort. TABLE 5.3 provides more facts about MDD.

| Prevalence |

|

| Comorbidity |

|

| Onset |

|

| Course |

|

| Gender Differences |

|

| Unless otherwise noted above, the source for information is American Psychiatric Association, 2013. |

In some cases, such as that of Marie Osmond in Case 5.2, depression emerges during pregnancy or within 4 weeks of giving birth; depression in this context is designated as having a peripartum onset (Wisner et al., 2013). Those most at risk for peripartum depression are women who have had recurrent depression before giving birth (Forty et al., 2006).

120

CASE 5.2 • FROM THE INSIDE: Peripartum Onset of Depression

After the birth of her seventh child, Marie Osmond developed peripartum depression:

I’m collapsed in a pile of shoes on my closet floor…. I sit with my knees pulled up to my chest. I barely move. It’s not that I want to be still. I am numb. I can tell I’m crying, but it’s not like tears I’ve shed before. My eyes feel as though they have moved deep into the back of my head. There is only hollow space in front of them. Dark, hollow space. I am as empty as the clothing hanging above me. Despite my outward appearance, I feel like a lifeless form.

I can hear the breathing of my sleeping newborn son in his bassinet next to the bed. My ten-year-old daughter, Rachael, opens the bedroom door and whispers, “Mom?” into the room, trying not to wake the baby. Not seeing me, she leaves. She doesn’t even consider looking in the closet on the floor. Her mother would never be there. She’s right. This person sitting on the closet floor is nothing like her mother. I can’t believe I’m here myself. I’m convinced that I’m losing my mind. This is not me.

I feel like I’m playing hide-and-seek from my own life, except that I just want to hide and never be found. I want to escape my body. I don’t recognize it anymore. I have lost any resemblance to my former self. I can’t laugh, enjoy food, sleep, concentrate on work, or even carry on a conversation. I don’t know how to go on feeling like this: the emptiness, the endless loneliness. Who am I? I can’t go on.

(Osmond et al., 2001)

Depression often occurs along with another disorder. In fact, depression and anxiety disorders co-occur about 50% of the time. Because of this high comorbidity, researchers propose that the two types of disorders have a common cause, presently unknown. In addition, although not common, depression can occur with psychotic features—hallucinations (e.g., in which a patient can feel that his or her body is decaying) or delusions (e.g., in which the patient believes that he or she is evil and living in hell).

Depression in Children and Adolescents

In a given 6-month period, 1–3% of elementary-school children and 5–8% of teenagers are depressed (Garber & Horowitz, 2002; Lewinsohn & Essau, 2002). Moreover, some clinicians and researchers are reporting depression among preschool children, evidenced by avoidance, decreased enthusiasm, and increased anhedonia (Luby et al., 2006). Younger children who are depressed are not generally considered to be at high risk of developing depression in adulthood. However, those who first become depressed as teenagers are considered to be at high risk for being depressed as adults (Lewinsohn, Rohde, et al., 1999; Rhode et al., 2013; Weissman, Wolk, Wickramaratne, et al., 1999; Weissman, Wickramaratne, et al., 2006). Teenage depression has far-reaching effects: Depressed teens are more likely than their nondepressed peers to drop out of school or to have unplanned pregnancies (Waslick et al., 2002).

Persistent Depressive Disorder

Persistent depressive disorder (dysthymia) A depressive disorder that involves as few as two symptoms of a major depressive episode but in which the symptoms persist for at least 2 years.

When symptoms of major depressive disorder persist for a long period of time, the person may be diagnosed with Persistent depressive disorder (dysthymia), characterized by depressed mood and as few as two unknown. In addition, other depressive symptoms that last for at least 2 years and that do not recede for longer than 2 months at any time during that period (see TABLE 5.4). Note that people can come to be diagnosed with this disorder if they have fewer symptoms of depression than necessary for MDD but have these symptoms for at least 2 years or they have MDD that lasts for at least 2 years (also referred to as chronic depression).

|

| Reprinted with permission from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, (Copyright ©2013). American Psychiatric Association. All Rights Reserved. |

121

CURRENT CONTROVERSY

Disruptive Mood Dysregulation Disorder: Overlabeling of Tantrums?

Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder (DMDD) is a depressive disorder in children characterized by persistent irritability and frequent episodes of out-of-control behavior. It is supposed to be a more accurate description of kids who have out-of-control rage episodes and were incorrectly labeled as having bipolar disorder and then were (inappropriately) treated for that disorder. The criteria for using this diagnosis, which is brand new in DSM-5, include:

- Severe, recurrent temper outbursts, including verbal or physical aggression, with a duration or intensity that is out of proportion to the situation and inconsistent with the child’s developmental level.

- These outbursts occur at least three times a week, on average.

- Even between outbursts, mood is persistently irritable or angry.

- This pattern starts between ages 6 and 10, occurs in at least two settings, continues for at least 1 year without letting up for 3 months, and is not exclusively the result of another mental disorder.

On the one hand, just as a diagnosis of bipolar disorder was overused to describe children with out-of-control rage episodes, a diagnosis of DMDD might label as mentally ill children who merely have a lot of tantrums, perhaps simply as a way to gain attention. Moreover, diagnosing a child with DMDD might focus on—and lead to treatment of—the child when the real problem is in the family.

On the other hand, the specifics of the criteria (e.g., severity, frequency, duration) should prevent diagnosing children who merely are sometimes grumpy or throw occasional tantrums. To apply this diagnosis, the child’s irritable mood must be persistent and daily, even when there is no reinforcement (such as attention) for a tantrum. The rages must occur in at least two settings (e.g., school and home) and not be an expected response to a home or school situation. This diagnosis might lead to fewer such children being put on bipolar medication because they will no longer be considered to have bipolar disorder.

CRITICAL THINKING Even with narrow criteria designed to prevent inappropriate diagnosis of bipolar disorder, won’t some clinicians apply (and overuse) this diagnosis to children who are merely “difficult” attention seekers? How can we prevent this?

(James Foley, College of Wooster)

Disruptive mood dysregulation disorder (DMDD) A depressive disorder in children characterized by persistent irritability and frequent episodes of out-of-control behavior.

Because symptoms are chronic, people with persistent depressive disorder often incorporate the symptoms into their enduring self-assessment, seeing themselves as incompetent or uninteresting. Whereas people with shorter-lasting MDD see their symptoms as happening to them, people with persistent depressive disorder often view their symptoms as an integral part of themselves (“This is just how I am”), like Mr. A, in Case 5.3. Moreover, people with persistent depressive disorder are less likely to experience the vegetative signs associated with an MDE (psychomotor retardation and changes in sleep, appetite, and weight; American Psychiatric Association, 2000). In addition, people who have persistent depressive disorder are generally younger than those with MDD. See TABLE 5.5 for more facts about persistent depressive disorder.

| Prevalence |

|

| Comorbidity |

|

| Onset |

|

| Course |

|

| Gender Differences |

|

| Source: The source for information is American Psychiatric Association, 2013. |

122

CASE 5.3 • FROM THE INSIDE: Persistent Depressive Disorder

Mr. A, a 28-year-old, single accountant, sought consultation because, he said, “I feel I am going nowhere with my life.” Problems at work included a recent critical job review because of low productivity, conflicts with his boss, and poor management skills. His fiancée recently postponed their wedding because she has doubts about their relationship, especially his remoteness, critical comments, and lack of interest in sex.

Describing himself as a pessimist who has difficulty experiencing pleasure or happiness, Mr. A has long felt a sense of hopelessness—of life not being worth living. His mother was hospitalized with [peripartum] depression after the birth of his younger sister; his father had a drinking problem. His high school classmates found him gloomy and “not fun.”

Although not troubled by thoughts of suicide nor significant vegetative signs of depression, Mr. A. does have months when his concentration is impaired, his energy level is lowered, and his interest in sex wanes. At such times, he withdraws from other people (although he always goes to work), staying in bed on weekends.

(Adapted from Frances & Ross, 1996, pp. 123–124)

Understanding Depressive Disorders

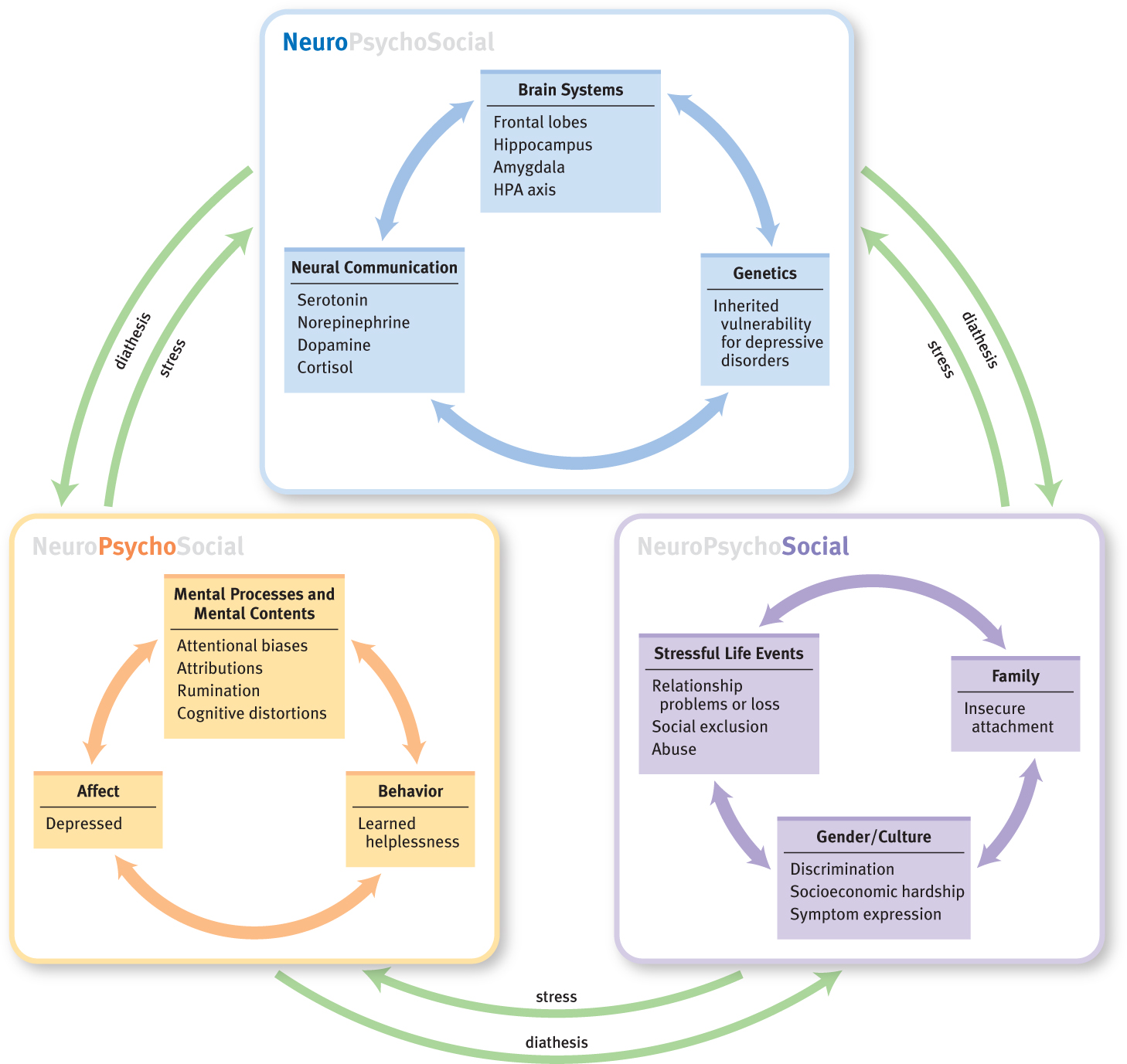

How do depressive disorders arise? Why do some people, but not others, suffer from them? Like all other psychological disorders, depressive disorders are best understood as arising from neurological, psychological, and social factors and the feedback loops among them. However, we must note that many of the factors that have been identified are correlational. As you know, correlation does not imply causation. In some cases, there is evidence for causal factors, but in most cases we cannot know whether a specific factor gives rise to depression or vice versa—or whether some third factor gives rise to both.

Neurological Factors

Neurological factors that contribute to depressive disorders can be classified into three categories: brain systems, neural communication, and genetics. Stress-related hormones—which underlie a specific kind of neural communication—are particularly important in understanding depressive disorders.

Brain Systems

Studies of depressed people have shown that they have unusually low activity in a part of the frontal lobe that has direct connections to the amygdala (a brain structure that is involved in fear and other strong emotions) and to other brain areas involved in emotion (Kennedy et al., 1997). The frontal lobe plays a key role in regulating other brain areas, and signals from it can inhibit activity in the amygdala. This finding hints that the depressed brain is not as able as the normal brain to regulate emotion. Moreover, this part of the frontal lobe has connections to the brain areas that produce the neurotransmitters dopamine, serotonin, and norepinephrine. Thus, this part of the frontal lobe may be involved in regulating the amounts of such neurotransmitters. This is important because these substances are involved in reward and emotion, which again hints that the brains of these people are not regulating emotion normally. Researchers have refined this general observation and reported that one aspect of depression—lack of motivated behavior—is specifically related to reduced activity in the frontal and parietal lobes (Milak et al., 2005).

Neural Communication

Researchers have long known that the symptoms of depression can be alleviated by medications that alter the activity of serotonin or norepinephrine (Arana & Rosenbaum, 2000). Indeed, when this fact was first discovered, some researchers thought that the puzzle of depression was nearly solved. However, we now know that the story is not so simple: Depression is not caused by too much or too little of any one specific neurotransmitter. Instead, the disorder arises in part from complex interactions among numerous neurotransmitters and depends on how much of each is released into the synapses, how long each neurotransmitter lingers in the synapses, and how the neurotransmitters interact with receptors in other areas of the brain that are involved in the symptoms of depression (Nemeroff, 1998).

123

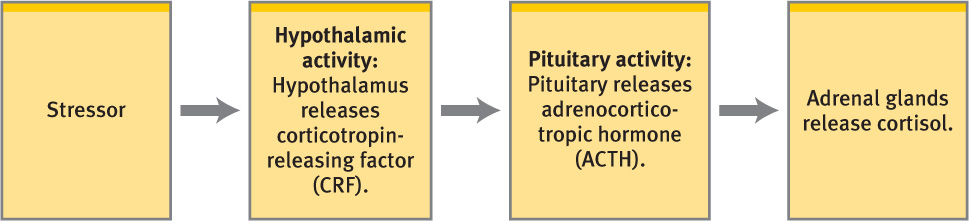

Stress-Related Hormones

The chemical story doesn’t end with neurotransmitters. Nemeroff (1998, 2008) formulated the stress–diathesis model of depression (which is to be distinguished from the general diathesis–stress model, discussed in Chapter 1). The stress–diathesis model of depression focuses on a part of the brain involved in the fight-or-flight response, the hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis (HPA axis). The HPA axis is particularly important because it governs the production of the hormone cortisol, which is secreted in larger amounts when a person experiences stress (see Figure 5.1). According to the stress–diathesis model, people with depression have an excess of cortisol circulating in their blood, which makes their brains prone to overreacting when they experience stress. Moreover, this stress reaction, in turn, alters the serotonin and norepinephrine systems, which underlie at least some of the symptoms of depression. Antidepressant medications can lower people’s cortisol levels and also decrease their depressive symptoms (Deuschle et al., 2003; Werstiuk et al., 1996).

The stress–diathesis model of depression receives support from several sources (Nemeroff, 2008). For instance, higher levels of cortisol are associated with decreases in the size of the hippocampus, which thereby impairs the ability to form new memories (of the sort that later can be voluntarily recalled)—which in turn may contribute to the decreased cognitive abilities that characterize depression. And, in fact, researchers have reported that parts of this brain structure are smaller in depressed people than in people who are not depressed (Neumeister et al., 2005; Neumeister et al., 2005), which suggests that stress affects the symptoms of depression in part by altering levels of cortisol, which in turn impairs the functioning of the hippocampus.

Genetics

Twin studies show that when one twin of a monozygotic (identical) pair has MDD, the other twin has a risk of also developing the disorder that is four times higher than when the twins are dizygotic [(fraternal) (Bowman & Nurnberger, 1993; Kendler et al., 1999a)]. Because monozygotic twins basically share all of their genes but dizygotic twins share only half of their genes, these results point to a role for genetics in this disorder. One possibility is that genes influence how a person responds to stressful events (Costello et al., 2002; Kendler et al., 2005). If a person is sensitive to stressful events, the sensitivity could lead to increased HPA axis activation (Hasler et al., 2004), which in turn could contribute to depression.

However, genes are not destiny. The environment clearly plays an important role in whether a person will develop depression (Hasler et al., 2004; Rice et al., 2002). Even with identical twins, if one twin is depressed, this does not guarantee that the co-twin will also be depressed—despite their having basically the same genes. Whether a person becomes depressed depends partly on his or her life experiences, including the presence of hardships and the extent of social support.

124

Psychological Factors

Particular ways that people think about themselves and events, in concert with stressful or negative life experiences, are associated with an increased risk of depression. In the following sections we consider psychological factors that can influence whether a person develops depression; these factors range from biases in attention to the effects of different ways of thinking to the results of learning.

Attentional Biases

People who are depressed are more likely to pay attention to sad or angry stimuli. For instance, they will pay more attention to sad or angry faces than to faces that display positive emotions (Gotlib, Kasch, et al., 2004; Gotlib, Krasnoperova, et al., 2004; Leyman et al., 2007); people who do not have this psychological disorder spend equal time looking at faces that express different emotions. This attentional bias has also been found for negative words and scenes, as well as for remembering depression-related—versus neutral—stimuli (Caseras et al., 2007; Gotlib, Kasch, et al., 2004; Mogg et al., 1995). Such an attentional bias may leave depressed people more sensitive to other people’s sad moods and to negative feedback from others, compounding their depressive thoughts and feelings.

GETTING THE PICTURE

Purestock/Getty Images

Dysfunctional Thoughts

As discussed in Chapter 2, Aaron Beck proposed that cognitive distortions are the root cause of many disorders. Beck (1967) has suggested that people with depression tend to have overly negative views about: (1) the world, (2) the self, and (3) the future, referred to as the negative triad of depression. These distorted views can cause and maintain chronically depressed feelings and depression-related behaviors. For instance, a man who doesn’t get the big raise he hoped for might respond with cognitive distortions that give rise to dysfunctional thoughts. He might think that he isn’t “successful” because he didn’t get the raise and therefore that he must be worthless (notice the circular reasoning). This man is more likely to become depressed than he would be if he didn’t have such dysfunctional thoughts (Gibb et al., 2007).

Rumination and Attributional Style

While experiencing negative emotions, some people reflect on these emotions and the events that led to them; during such ruminations, they might say to themselves: “Why do bad things always happen to me?” or “Why did they say those hurtful things about me? Is it something I did?” (Nolen-Hoeksema & Morrow, 1991). Such ruminative thinking has been linked to depression (Just & Alloy, 1997; Nolen-Hoeksema, 2000; Nolen-Hoeksema & Morrow, 1991, 1993).

125

People who consistently attribute negative events to their own qualities—called an internal attributional style—are more likely to become depressed. In one study, mothers-to-be who had an internal attributional style were more likely to be depressed 3 months after childbirth than were mothers-to-be who had an external attributional style—blaming negative events on qualities of others or on the environment (Peterson & Seligman, 1984). Similarly, college students who tended to blame themselves (rather than external factors) for negative events were more likely than those who did not to become depressed after receiving a bad grade (Metalsky et al., 1993).

Three particular aspects of attributions are related to depression: whether the attributions are internal or external, stable (enduring causes) or unstable (local, transient causes), and global (general, overall causes) or specific (particular, precise causes). People who tend to attribute negative events to internal, stable, and global factors have a negative attributional style. These people not only make negative predictions about the future (e.g., “Even if I find another girlfriend, she’ll dump me too,” Abramson et al., 1999) but also are vulnerable to becoming depressed when negative events occur (Abramson et al., 1978).

In fact, people who consistently make stable and global attributions for negative events—whether to internal or external causes—are more likely to feel hopeless in the face of negative events and come to experience hopelessness depression, a form of depression in which hopelessness is a central element (Abramson et al., 1989).

GETTING THE PICTURE

Spencer Platt/Getty Images

Learned Helplessness

Hopelessness depression is not always based on incorrect attributions. It can arise from situations in which undesirable outcomes do occur and the person is helpless to change the situation, such as may occur when children are subjected to physical abuse or neglect (Widom et al., 2007). Such circumstances lead to learned helplessness, in which a person gives up trying to change or escape from a negative situation (Overmier & Seligman, 1967; see Chapter 2 for a more detailed discussion). For example, people in abusive relationships might become depressed if they feel that they cannot escape the relationship and that no matter what they do, the situation will not improve.

126

Social Factors

Depression is also associated with a variety of social factors, including stressful life events (including in personal relationships), social exclusion, and social interactions (which are affected by culture). These social factors can affect whether depression develops or persists.

Stressful Life Events

In approximately 70% of cases, an MDE occurs after a significant life stressor, such as getting fired from a job or losing an important relationship. Such events are particularly likely to contribute to a first or second depressive episode (Lewinsohn, Allen, et al., 1999; Tennant, 2002).

It might seem obvious that negative life events can lead to depression, but separating possible confounding factors and trying to establish causality have challenged researchers. For instance, people who are depressed (or have symptoms of depression) may have difficulty doing their job effectively; they may experience stressors such as problems with their coworkers and supervisors, job insecurity, or financial worries. In such cases, the depressive symptoms may cause the stressful life events, not be caused by them. Alternatively, some people, by virtue of their temperament, may seek out situations or experiences that are stressful; for example, some soldiers volunteer to go to the front line (Foley et al., 1996; Lyons et al., 1993). The point is that the relationship between stressful life events and depression may not be as straightforward as it might seem.

Social Exclusion

Feeling the chronic sting of social exclusion—being pushed toward the margins of society—is also associated with depression. For instance, those who are the targets of prejudice are more likely than others to become depressed. Such groups include homosexuals who experience community alienation or violence (Mills et al., 2004), those from lower socioeconomic groups (Field et al., 2006; Henderson et al., 2005; Inaba et al., 2005), and, in some cases, the elderly (Hybels et al., 2006; Sachs-Ericsson et al., 2005).

Some studies find that Latinos and African Americans experience more depression than other ethnic groups in the United States; a closer look at the data, however, suggests that socioeconomic status, rather than ethnic or racial background per se, is the variable associated with depression (Bromberger et al., 2004; Gilmer et al., 2005).

Social Interactions

To a certain extent, emotions can be contagious: People can develop depression, sadness, anxiety, or anger by spending time with someone who is already in such a state (Coyne, 1976; Segrin & Dillard, 1992). For instance, one study found that roommates developed symptoms of depression after 3 weeks of living with someone who was depressed (Joiner, 1994), and other studies find similar results (Haeffel & Hames, in press).

Another factor associated with depression is a person’s attachment style in infancy, which can affect the way adults typically interact in their personal relationships (Ainsworth et al., 1978; Bowlby, 1973, 1979). Adults tend to display one of the following three patterns:

- Secure attachment. Adults with this style generally display a positive relationship style.

- Avoidant attachment. Adults with this style are emotionally distant from others.

- Anxious-ambivalent attachment. Adults with this style chronically worry about their relationships.

127

Adults who are characterized by the second and third forms of attachment are more vulnerable to depression: Those with anxious-ambivalent attachment are the most likely to experience episodes of depression, followed by those with avoidant attachment. Adults with secure attachment are least likely to do so (Bifulco et al., 2002; Cooper et al., 1998; Fonagy et al., 1996).

Culture

A person’s culture and context can influence how the person experiences and expresses depressive symptoms (Lam et al., 2005). For instance, in Asian and Latin cultures, people with depression may not mention mood but may instead talk about “nerves” or describe headaches. Similarly, depressed people in Zimbabwe tend to complain about fatigue and headaches (Patel et al., 2001). In contrast, some depressed people from Middle Eastern cultures may describe problems with their heart, and depressed Native Americans of the Hopi people may report feeling heartbroken (American Psychiatric Association, 2000).

The influence of culture doesn’t end with the way symptoms are described. Each culture—and subculture—also leads its members to take particular symptoms more or less seriously. For instance, in cultures that have strong prohibitions against suicide, having suicidal thoughts is a key symptom; in cultures that emphasize being productive at work, having difficulty functioning well at work is considered a key symptom (Young, 2001).

A particular culture can also be influenced by another culture and change accordingly. Consider that depressed people in China have typically reported mostly physical symptoms of depression, but these reports are changing as China becomes increasingly exposed to Western views of depression (Parker et al., 2001).

Gender Difference

In North America, women are about twice as likely as men to be diagnosed with depression (Marcus et al., 2005), and studies in Europe find a similar gender difference (Angst et al., 2002; Dalgard et al., 2006). Research results indicate that the gender difference arises at puberty and continues into adulthood (Alloy & Abramson, 2007; Jose & Brown, 2008).

One explanation for the gender difference in rates of depression is that girls’ socialization into female roles can lead them to experience more body dissatisfaction, which in turn can make them more vulnerable to automatic negative thoughts that lead to depression (Cyranowski et al., 2000; Nolen-Hoeksema & Girgus, 1994).

Another explanation for this difference focuses on a ruminative response to stress: Women are more likely than men to mull over a stressful situation, whereas men more often respond by distracting themselves and taking action (Nolen-Hoeksema, 1987; Nolen-Hoeksema & Morrow, 1993; Vajk et al., 1997). A ruminative pattern can be unlearned: College students who learned to use distraction more and rumination less improved their depressed mood (Nolen-Hoeksema & Morrow, 1993).

An additional consideration is that women may be more likely than men to report symptoms of depression, perhaps because they are less concerned about appearing “strong”; thus, women may not necessarily experience more of these symptoms than men (Sigmon et al., 2005).

Danita Delimont/Getty Images

Furthermore, biological differences—such as specific female hormonal changes involved in puberty—may contribute to this gender difference (Halbreich & Kahn, 2001; Steiner et al., 2003). A role for this biological factor is consistent with the finding that before puberty, boys and girls have similar rates of depression (Cohen et al., 1993). Additional evidence that hormones influence depression is the fact that women and men have similar rates of the disorder after women have reached menopause (and hence their levels of female hormone are greatly reduced) (Hyde et al., 2008).

128

The different explanations for the gender difference are not mutually exclusive, and these factors may interact with one another (Hyde et al., 2008). For instance, girls who enter puberty early are more likely to become depressed (Kaltiala-Heino et al., 2003), perhaps in part because their early physical development makes them more likely to be noticed and teased about their changing bodies, which in turn can lead to dissatisfaction with and rumination about their bodies. Let’s examine more broadly how feedback loops contribute to depression.

Feedback Loops in Understanding Depressive Disorders

How do neurological, psychological, and social factors interact through feedback loops to produce depression? As we noted in the section on genetics, some people are more vulnerable than others to stress. For these people, the HPA axis is highly responsive to stress (and often the stress is related to social factors). For example, abuse or neglect at an early age, with accompanying frequent or chronic increase in the activity of the HPA axis, can lead cortisol-releasing cells to over respond to any stressor—even a mild one (Nemeroff, 1998). In fact, college students with a history of MDD reported feeling more tension and responded less well after a stressful cognitive task (one that, unknown to these participants, was impossible to solve) than college students with no history of MDD (Ilgen & Hutchison, 2005). These results support the notion that people who are vulnerable to MDD are affected by stressors differently than are people without such a vulnerability (Hasler et al., 2004).

A cognitive factor that makes a person vulnerable to depression, such as a negative attributional style, ruminative thinking, or dysfunctional thoughts (all psychological factors), can amplify the negative effects of a stressor. In fact, such cognitive factors can lead people to be hypervigilant for stressors or to interpret neutral events as stressors, which in turn activates the HPA axis. This neurological response then can lead such people to interact differently with others (social factor)—making less eye contact, being less responsive, and becoming more withdrawn.

Researchers have identified other ways that neurological, psychological, and social factors create feedback loops in depression. According to James Coyne’s interactional theory of depression (Coyne, 1976; Coyne & Downey, 1991; Joiner et al., 1999), someone who is neurologically vulnerable to depression (perhaps because of genes or neurotransmitter abnormalities) may, through verbal and nonverbal behaviors (psychological factor), alienate people who would otherwise be supportive (social factor; Nolan & Mineka, 1997). For example, researchers have found that depressed undergraduates are more likely than nondepressed undergraduates to solicit negative information from happy people—which in turn can lead happier people to reject the depressed questioner (Wenzlaff & Beevers, 1998). And soliciting negative information (and similar behaviors) could arise from negative attributions and views about self and the environment (psychological factors), which in turn could arise from group interactions (social factors), such as being teased or ridiculed, or modeling the behavior of someone else.

129

In short, people’s psychological characteristics affect how they interpret events and how they behave, which in turn influences how they are treated in social interactions, which then influences their beliefs about themselves and others (Casbon et al., 2005). And all this is modulated by whether the person is neurologically vulnerable to depression. Figure 5.2 illustrates the feedback loops.

130

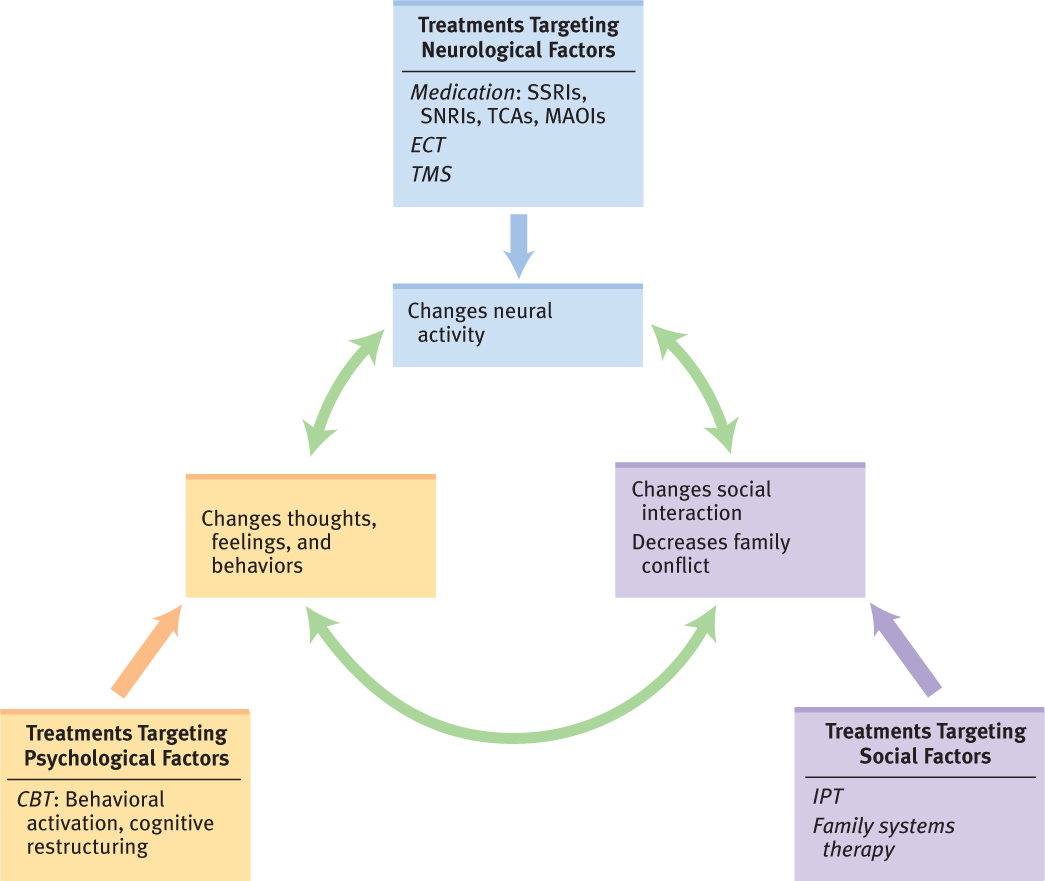

Treating Depressive Disorders

Different treatments target different factors that contribute to depression. However, successful treatment of any one factor will affect the others. For example, improving disrupted brain functioning will alter a person’s thoughts, mood, and behavior, and interactions with others.

Targeting Neurological Factors

In treating depressive disorders, clinicians rely on two major types of treatment that directly target neurological factors: medication and brain stimulation.

Medication

Several types of medications are commonly prescribed for depression, but it can take weeks for one of these medications to improve depressed mood. Antidepressant medications include the following:

- Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), such as fluoxetine (Prozac), paroxetine (Paxil), and sertraline (Zoloft). SSRIs slow the reuptake of serotonin from synapses. Because these antidepressants affect only certain receptors, they have fewer side effects than other types of antidepressant medications, which can make people less likely to stop taking them (Anderson, 2000; Beasley et al., 2000). However, SSRIs are the only type of antidepressant to have the side effect of decreased sexual interest, which can lead some patients to stop taking them (Brambilla et al., 2005). Many patients also find that the same dose of an SSRI brings less benefit over time (Arana & Rosenbaum, 2000).

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) Medications that slow the reuptake of serotonin from synapses.

- Tricyclic antidepressants (TCAs), such as amitriptyline (Elavil). TCAs are named after the three rings of atoms in their molecular structure. These medications have been used since the 1950s to treat depression and, until SSRIs became available, were the most common medication to treat this disorder. TCAs are generally as effective as Prozac for depression (Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, 1999). The side effects of TCAs differ from those of SSRIs: The most common side effects include low blood pressure, blurred vision, dry mouth, and constipation (Arana & Rosenbaum, 2000).

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) Older antidepressants named after the three rings of atoms in their molecular structure.

- Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs), such as phenelzine (Nardil). Some neurotransmitters, such as serotonin, dopamine, and norepinephrine, are classified as monoamines; monoamine oxidase is a naturally produced enzyme that breaks down monoamines in the synapse. MAOIs inhibit this chemical breakdown, so the net effect is to increase the amount of neurotransmitter in the synapse. MAOIs are more effective for treating atypical depression (Cipriani et al., 2007) than typical depression. An MAOI is now available as a skin patch, which avoids absorption via the gastrointestinal tract; this method reduces the medical risks of oral MAOIs, including potentially fatal blood pressure changes that are associated with eating tyramine-rich foods such as cheese and wine (Patkar et al., 2006).

Monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs) Antidepressant medications that increase the amount of monoamine neurotransmitter in synapses.

SSRIs have been the most popular antidepressants, in part because they have the fewest side effects. By 2004, however, mental health professionals and laypeople were raising concerns about whether SSRI use was associated with increased suicide rates. Studies comparing SSRIs to other antidepressants did, in fact, find a greater risk for suicidal thoughts and suicide attempts in children and adolescents taking such medications (Martinez et al., 2005); these findings led to a warning label indicating that the medications may increase the risk of suicide in children who take them and that the children should be closely monitored for suicidal thoughts or behaviors or for an increase in depressive symptoms. Since the warning label was mandated, additional research suggests that the benefits of SSRI antidepressants for youngsters outweigh any risk of suicide, although people taking them should continue to be carefully monitored (Bridge et al., 2007).

131

Some newer antidepressants, such as venlafaxine (Effexor) and duloxetine (Cymbalta), affect neurons that respond both to serotonin and norepinephrine; such medications are sometimes referred to as serotonin/norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs). Other new antidepressants affect noradrenaline (the alternative term for norepinephrine) and serotonin and are referred to as noradrenergic and specific serotonergic antidepressants (NaSSAs, where Na stands for “noradrenergic”). The antidepressant mirtazapine (Remeron) is a NaSSA. These new medications can help some patients who do not respond to the earlier medications.

Don Farrall/Getty Images

Some people with depression who do not want to take prescription medication have successfully used an extract from a flowering plant called St. John’s wort (Hypericum perforatum). Results of meta-analytic studies comparing St. John’s wort to prescription antidepressants and placebos indicate that the herbal medication can help patients with mild to moderate depression, and sometimes—but less commonly—even those with severe depression (Linde et al., 2005; Linde et al., 2008). Patients taking St. John’s wort report fewer side effects than do patients taking prescription medications (Linde et al., 2008); the most common side effect is dry mouth or dizziness.

Brain Stimulation: ECT and TMS

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) A procedure that sends electrical pulses into the brain to cause a controlled brain seizure, in an effort to reduce or eliminate the symptoms of certain psychological disorders.

When patients with depression are not helped by medication or by other commonly employed treatments, they may receive electroconvulsive therapy (ECT), which consists of electrical pulses that are sent into the brain to cause a controlled brain seizure. This seizure may reduce or eliminate the symptoms of certain psychological disorders, most notably some forms of depression. ECT may be used when a patient: (1) has severe depression that has not improved significantly with either medication or psychotherapy, (2) cannot take medication because of side effects or other medical reasons, or (3) has a psychotic depression (depression with psychotic features) that does not respond to medication (Fink, 2001; Lam et al., 1999).

Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) A procedure that sends sequences of short, strong magnetic pulses into the brain via a coil placed on the scalp, which is used to reduce or eliminate the symptoms of certain psychological disorders.

In the ECT procedure, electrical pulses are delivered via electrodes placed on the scalp. Just before ECT treatment, the patient receives a muscle relaxant, and the treatment occurs while the patient is under anesthesia. Because of the risks associated with anesthesia, ECT is performed in a hospital and may require a hospital stay. ECT for depression is usually administered 2 to 3 times a week over several weeks, for a total of 6 to 12 sessions (Shapira et al., 1998; Vieweg & Shawcross, 1998). Depressive symptoms typically decrease a few weeks after the treatment begins, although scientists don’t yet understand exactly how ECT provides relief (Pagnin et al., 2004). Some people receiving ECT suffer memory loss for events that occurred during a brief period of time before the procedure (Semkovska & McLoughlin, 2010).

Depressed patients who did not respond to antidepressants commonly relapse after receiving ECT: At least half of these patients experience another episode of depression over the following 2 years (Gagne et al., 2000; Sackheim et al., 2001). To minimize the risk of a relapse, patients usually begin taking antidepressant medication after ECT ends.

132

Some patients with depression benefit from transcranial magnetic stimulation. In contrast to ECT, which relies on electrical impulses, Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) uses sequences of short, strong magnetic pulses sent into the brain via a coil placed on the scalp. Each pulse lasts only 100–200 microseconds. TMS has varying effects on the brain, depending on the exact location of the coil and the frequency of the pulses, and researchers are still working to understand how the magnetic field affects brain chemistry and brain activity (George et al., 1999; Wassermann et al., 2008). In some encouraging studies, about half of the depressed patients who did not improve with medication were treated successfully enough with TMS that they did not need to receive ECT (Epstein et al., 1998; Figiel et al., 1998; Klein et al., 1999). Nevertheless, ECT generally is more effective than TMS (Slotema et al., 2010), but TMS is easier to administer and causes fewer side effects than ECT. However, unlike with ECT, researchers have yet to establish definitive guidelines for TMS that govern critical features of the treatment, such as the positioning of the coils that deliver magnetic pulses and how often the treatment should be administered (Holtzheimer & Avery, 2005). In 2008, the Federal Drug Administration approved TMS as a treatment for depression to be used when medication treatments have failed.

Targeting Psychological Factors

Biomedical treatments are not the only treatments available for depression. A variety of treatments are designed to alter psychological factors—changing the patient’s behaviors, thoughts, and feelings.

Behavioral Therapy and Methods

Behavior therapy rests on two ideas: (1) Maladaptive behaviors stem from previous learning, and (2) new learning can allow patients to develop more adaptive behaviors, which in turn can change cognitions and emotions. Behavioral methods focus on identifying depressive behaviors and then changing them; such methods focus on the ABCs of an unwanted behavior pattern:

- the antecedents of the behavior (the stimuli that trigger the behavior),

- the behavior itself, and

- the consequences of the behavior (which may reinforce the behavior).

Behavior therapy The form of treatment that rests on the ideas that: (1) maladaptive behaviors stem from previous learning, and (2) new learning can allow patients to develop more adaptive behaviors, which in turn can change cognitions and emotions.

For instance, being socially isolated or avoiding daily activities can lead to depressive thoughts and feelings or can help maintain them (Emmelkamp, 1994). Changing these behaviors can, in turn, increase the opportunities to receive positive reinforcement (Lewinsohn, 1974).

Specific techniques to change such behaviors are collectively referred to as behavioral activation (Gortner et al., 1998). These techniques include self-monitoring (keeping logs of activities, thoughts, or behaviors), scheduling daily activities that lead to pleasure or a sense of mastery, and identifying and decreasing avoidant behaviors. Behavioral activation may also include problem solving—identifying obstacles that interfere with achieving a goal and then developing solutions to circumvent or eliminate those obstacles. For instance, a depressed college student may feel overwhelmed at the thought of asking for an extension for an overdue paper. The student and therapist work together to solve the problem of how to go about asking for the extension; they come up with a realistic timetable to complete the paper and discuss how to talk with the professor.

Behavioral activation techniques may initially be aversive to a person with depression because they require more energy than the person feels able to summon; however, mood improves in the long term. In fact, behavioral activation is superior to cognitive therapy techniques in treating both moderate and severe depression (Dimidjian et al., 2006).

133

Cognitive Therapy and Methods

Cognitive therapy The form of treatment that rests on the ideas that: (1) mental contents influence feelings and behavior; (2) irrational thoughts and incorrect beliefs lead to psychological problems; and (3) correcting such thoughts and beliefs will therefore lead to better mood and more adaptive behavior.

In contrast to behavior therapy, Cognitive therapy rests on these ideas: (1) Mental contents—in particular, conscious thoughts—influence a person’s feelings and behavior; (2) irrational thoughts and incorrect beliefs contribute to mood and behavior problems; and (3) correcting such thoughts and beliefs, sometimes referred to as cognitive restructuring, leads to more rational thoughts and accurate beliefs and therefore will lead to better mood and more adaptive behavior.

The methods of cognitive therapy often require patients to collect data to assess the accuracy of their beliefs, which are often irrational and untrue (Hollon & Beck, 1994). This process can relieve some patients’ depression and can prevent or minimize further episodes of depression (Teasdale & Barnard, 1993; Teasdale et al., 2002).

Consider Kay Jamison: She felt that she was a burden to her friends and family and that they would all be better off if she were dead. In cognitive therapy, the therapist would explore the accuracy of these beliefs: Why did she think she was a burden? What evidence did she have to support this conclusion? How might friends or family react if she told them that they’d be better off if she were dead? A cognitive therapist might even suggest that she talk to them about her beliefs and listen to their responses to determine whether her beliefs were accurate. Most likely, her friends and family would not agree that they’d be better off if she were dead.

Cognitive-Behavior Therapy

Cognitive-behavior therapy (CBT) The form of treatment that combines methods from cognitive and behavior therapies.

Although cognitive and behavior therapies began separately, their approaches are complementary and are frequently combined; when methods from cognitive and behavior therapies are implemented in the same treatment, it is called Cognitive-behavior therapy (CBT). CBT, particularly when it includes behavioral activation, is often about as successful as medication (Sava et al., 2009; Spielmans et al., 2011, TADS Team, 2007). In some ways, CBT may be better than medication. For example, the side effects of medication may lead patients to stop taking it: Various studies have found that about 75% of patients either stop taking their antidepressant medication within the first 3 months or take less than an optimal dose (Mitchell, 2007). And when patients stop taking medication, a high proportion of them relapse. Furthermore, even when medication is successful, research suggests that people at risk for further episodes should continue to take the medication for the rest of their lives to prevent relapses (Hirschfield et al., 1997). In contrast, the beneficial effects of CBT can persist after treatment ends (Hollon et al., 2005); CBT is an alternative that need not be administered for life.

As usual, CBT and medication can be used together. In fact, studies have shown that a combination of CBT and medication is more effective than medication alone—even for severely depressed adolescents and adults (TADS Team, 2007; Thase et al., 1997). In addition, after treatment with antidepressants has ended, a patient’s residual symptoms of depression can be reduced through CBT; this supplemental CBT can reduce the relapse rate (Fava et al., 1998a, 1998b).

Targeting Social Factors

Treatment for depression can also directly target a social factor—personal relationships. Such treatment is designed to increase the patient’s positive interactions with others and minimize the negative interactions.

134

Interpersonal Therapy

Interpersonal therapy (IPT) The form of treatment that is intended to improve the patient’s skills in relationships so that they become more satisfying.

Interpersonal therapy (IPT) emphasizes the links between mood and events in a patient’s recent and current relationships (Klerman et al., 1984). The theory underlying IPT is that symptoms of psychological disorders such as depression become exacerbated when a patient’s relationships aren’t functioning well. The goal of IPT is thus to improve the patient’s skills in relationships so that they become more satisfying; as relationships improve, so do the patient’s thoughts and feelings, and the symptom of depression lessen. IPT addresses four general aspects of relationships, generally in about 16 sessions:

- a deficiency in social skills or communication skills, which results in unsatisfying social relationships;

- persistent, significant conflicts in a relationship;

- grief about a loss; and

- changes in interpersonal roles (for example, a partner with a new job may have become less emotionally available).

IPT is effective in a wide range of circumstances and settings (Cuijpers et al., 2011). For example, in an innovative study of depressed people in 30 Ugandan rural villages, researchers randomly assigned depressed residents from 15 villages to group IPT, consisting of 16 weeks of 90-minute sessions. The depressed residents from the other 15 villages received no treatment (the control group). Those who received group IPT had a significant decrease in their depressive symptoms (and were better able to provide for their families and participate in community activities) than those in the control group (Bolton et al., 2003).

IPT has also successfully reduced the occurrence of peripartum depression in pregnant women at high risk for the disorder (Zlotnick et al., 2006). In addition to alleviating depressive symptoms, occasional additional “maintenance” sessions of IPT—either alone or in combination with CBT—may prevent relapse (Frank et al., 2007; Klein et al., 2004).

Systems Therapy: A Focus on the Family

A family’s functioning also may be a target of treatment; this usually occurs when a family member’s depression is related either to a maladaptive pattern of interaction within the family or to a conflict that arose within the family. For example, conflicts—particularly over values—may arise within families that have immigrated to the United States; immigrant parents and their children who grow up in the United States may experience tension because what the parents want for their children conflicts with what the children (as they become adults) want for themselves. Immigrant parents from Mexico, for instance, may want to be very involved in their children’s lives, just as they would be in their native hometown. But their children, growing up in the United States, may come to resent what the children perceive as their parents’ intrusive and controlling behavior (compared to the parents of their non-immigrant peers) (Santisteban et al., 2002). The parents, in turn, may think that their children are rejecting both their Mexican heritage and the parents themselves. Caught between two cultures—the old and the new—and wanting to maintain aspects of their heritage but also feel “American,” the resulting conflict can contribute to depression (Hovey, 1998, 2000).

Such problems in families may be treated with systems therapy, which is designed to change the communication or behavior patterns of one or more family members. According to this approach, the family is a system that strives to maintain homeostasis, a state of equilibrium, so that change in one member affects other family members. Systems therapy is guided by the view that when one member changes (perhaps through therapy), change is forced on the rest of the system (Bowen, 1978; Minuchin, 1974). To a family systems therapist, the “patient” is the family; systems therapy focuses on communication and power within the family. The symptoms of a particular family member are understood to be a result of that person’s intentional or unintentional attempts to maintain or change a pattern within the family or to convey a message to family members.

135

Feedback Loops in Treating Depressive Disorders

The goals of any treatment for depressive disorders are ultimately the same:

- to reduce symptoms of distress and depressed mood as well as negative or unrealistic thoughts about the self (psychological factors),

- to reduce problems related to social interactions—such as social withdrawal—and to make social interactions more satisfying and less stressful (social factors), and

- to correct imbalances in the brain associated with some of the symptoms, such as by normalizing neurotransmitter functioning or hormone levels (neurological factors).

Treatments that target one type of factor also affect other factors. CBT, for instance, not only can reduce psychological symptoms but can also change brain activity (Goldapple et al., 2004), improve physical symptoms (including disrupted sleep, appetite, and psychomotor symptoms), and improve social relations. Moreover, medication for depression works both through its effects on neurological functioning and through the placebo effect (see Chapter 4 for a discussion about the placebo effect). Thus, a depressed patient’s beliefs (psychological factor) can account for much of the effect of antidepressant medication. Figure 5.3 illustrates the various treatments discussed, the targets of treatments for depressive disorders, and the feedback loops that arise with successful treatment.

Note that Figure 5.3 lists the various types of treatment for depressive disorders, sorted into the three types of factors; in two cases, we go one step further and list specific types of drugs and specific CBT methods. Why are we specific with only these two forms of treatment? Because these forms of treatment have been studied the most extensively, and hence more is known about which specific medications and CBT methods are most likely to reduce symptoms and improve quality of life. Rigorous studies of other types of treatments are less common, and hence less is known about the specific methods that are most likely to be effective. You will find this same disparity in knowledge reflected in subsequent figures that illustrate feedback loops of treatments for other disorders (most of these types of figures can be found on the book’s website).

136

Now that we’ve discussed depressive disorders, let’s look back at what we know about Kay Jamison thus far and see whether MDD is the diagnosis that best fits her symptoms. She experienced depressed moods, anhedonia, fatigue, and feelings of worthlessness. She also had recurrent thoughts of death, as well as difficulty concentrating. Taken together, these symptoms seem to meet the criteria for MDD. However, she also has symptoms that may support the diagnosis of another mood disorder. We examine those building blocks in the following section.

Thinking Like A Clinician

Suppose that a friend began to sleep through morning classes, seemed uninterested in going out and doing things, and became quiet and withdrawn. What could you conclude or not conclude based on these observations? If you were concerned that these were symptoms of depression, what other symptoms would you look for? If your friend’s symptoms did not appear to meet the criteria for an MDE, what could you conclude or not conclude? If your friend was, in fact, suffering from depression, how might the three types of factors explain the depressive episode? What treatments might be appropriate?