5.3 Suicide

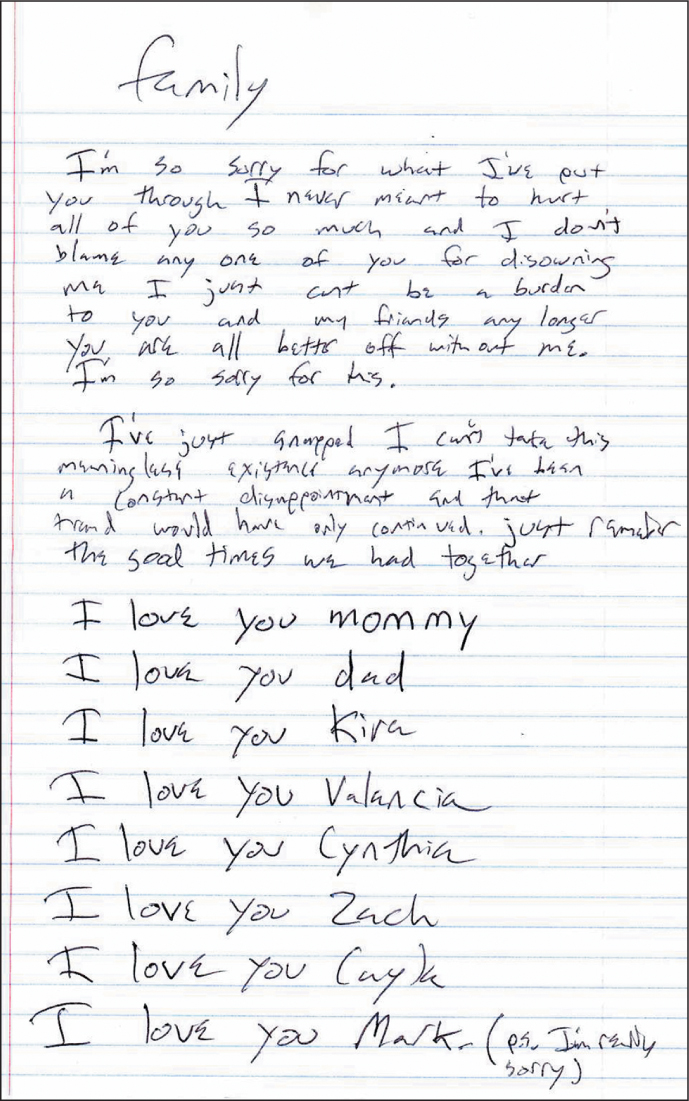

On more than one occasion, Kay Jamison seriously contemplated suicide. One day, when deeply depressed, she did more than think about it—she attempted suicide. She was seeking relief from her pain and for the pain she felt she was inflicting on her family and friends:

In a perverse linking with my mind I thought that…I was doing the only fair thing for the people I cared about; it was also the only sensible thing to do for myself. One would put an animal to death for far less suffering.

When Jamison attempted suicide, she was already receiving treatment for her disorder; in contrast, a majority of people who die by suicide have an untreated mental disorder, most commonly depression. Jamison’s attempt was foiled. She later describes being grateful that she continued living. The hopelessness that she had felt went away, and she was able to enjoy life again.

Suicidal Thoughts and Suicide Risks

In the United States and Canada, suicide is ranked 10th among causes of death (CDC, 2010a; Statistics Canada, 2005). Approximately 32,000 people die by suicide each year in the United States (CDC, 2005), which constitutes about 1% of all deaths per year (McIntosh, 2003). Worldwide, suicide is the second most frequent cause of death among women under 45 years old (tuberculosis ranks first), and it is the fourth most frequent cause among men under 45 (after road accidents, tuberculosis, and violence; WHO, 1999). TABLE 5.10 lists more facts about suicide.

| Prevalence |

|

| Gender Differences |

|

| Cultural Differences |

|

Thinking About, Planning, and Attempting Suicide

Suicidal ideation Thoughts of suicide.

When suffering from a mood disorder, people may have thoughts of death or thoughts about committing suicide, known as Suicidal ideation (Rihmer, 2007). But suicidal ideation does not necessarily indicate the presence of a psychological disorder or an actual suicide risk. Approximately 10–18% of the general population—including both those with and without disorders—has at some point had suicidal thoughts (Weissman, Bland, et al., 1999). One study found that 6% of people who were healthy and had never been depressed occasionally thought about suicide (Farmer et al., 2001). Suicidal thoughts may range from believing that others would be better off if the person were dead (which Jamison had) to specific plans to commit suicide.

147

Approximately 30% of those who have thoughts of suicide have also conceived of a plan (Kessler, Borges, et al., 1999). Even having a plan does not by itself indicate that a person is at risk for suicide. However, certain behaviors can suggest serious suicidal intent and can serve as warning signs (Packman et al., 2004):

- giving away possessions,

- saying goodbye to friends or family members,

- talking about death or suicide generally or about specific plans to commit suicide,

- threatening to commit suicide, and

- rehearsing a plan for suicide.

Not everyone who plans or is about to commit suicide displays such warning signs.

For some people, suicidal thoughts or plans do turn into actions. Certain methods of suicide are more lethal than others, and the more lethal the method, the more likely it is that the suicide attempt will result in death or serious medical problems. For instance, shooting, hanging, and jumping from a high place are more lethal than taking pills and cutting a vein. In the latter situations, the person often has at least a few minutes to seek help after having acted. Some people may be very ambivalent about suicide and so may attempt suicide with a less lethal method or try to ensure that they are found by others before any lasting damage is done. Unfortunately, these suicide attempts may still end in death because the help the person had anticipated may not materialize. Other people who attempt suicide do not appear to be ambivalent; they may or may not display warning signs but will follow through unless someone or something intervenes (Maris, 2002).

148

Not all acts associated with suicide—such as certain types of skin cutting—are, in fact, suicide attempts. Such deliberate but nonlethal self-harming is sometimes referred to as parasuicidal behavior. People may harm themselves without any suicidal impulse because they feel numb or because such self-harming behaviors allow them to “feel something” (Linehan, 1981). Alternatively, some people deliberately harm themselves to elicit particular reactions from others. Parasuicidal behavior is discussed in more detail in Chapter 13.

Risk and Protective Factors for Suicide

The risk of suicide is higher for people who have a psychological disorder—whether officially diagnosed or not—than for those who do not have a disorder. The three most common types of disorders among those who commit suicide are (Brown et al., 2000; Duberstein & Con-well, 1997; Isometsä, 2000; Moscicki, 2001):

- major depressive disorder (50%),

- personality disorders (40%), and

- substance-related disorders (up to 50% of those who commit suicide are intoxicated by alcohol at the time of their death).

People who commit suicide may have more than one of these disorders. Recognizing that people with disorders other than mood disorders may contemplate suicide, DSM-5 includes a question about suicidal ideation in its cross-cutting symptoms assessment (described in Chapter 3) (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Substance use or abuse plays a pivotal role in many suicide attempts because drugs and alcohol can cloud a person’s judgment and ability to reason. A history of being impulsive is another significant risk factor for suicide (Sánchez, 2001). Impulsive people may not exhibit warning signs of serious suicidal intent.

Beyond the presence of specific psychological disorders or impulsivity, another strong predictor of completed suicide is a history of past suicide attempts (Moscicki, 1997; Oquendo et al., 2007). Specifically, people who previously made serious attempts are more likely subsequently to die by suicide than are those who did not make serious attempts (Ivarsson et al., 1998; Stephens et al., 1999). Additional risk factors are listed in TABLE 5.11. Those at risk may benefit from early evaluation and treatment.

One group at increased risk for suicide is gays and lesbians, particularly during adolescence (Ramafedi, 1999). The increased risk, however, stems primarily from the social exclusion and discrimination experienced by these people (Igartua et al., 2003). Among homosexuals, suicide is most likely during the period when disclosing their homosexuality to immediate family members (Igartua et al., 2003). In addition, military personnel in certain settings are at high risk for committing suicide, probably because of the strain on family relationships caused by long and repeated tours of duty, combat-related stress, substance abuse, and legal and financial problems.

Despite such risks, most people who are depressed or have thoughts of suicide do not actually try to kill themselves. Even when in the blackest suicidal despair, specific factors can reduce the risk of a suicide attempt: receiving support from family and friends, holding religious or cultural beliefs that discourage suicide, and getting prompt and appropriate treatment for any depression or substance abuse. Additional protective factors are listed in TABLE 5.11.

| Risk Factors |

|

| Protective Factors |

|

| Source: Adapted from Sánchez, 2001, Appendix A. |

149

Understanding Suicide

To understand why some people commit suicide, we now turn to examine relevant neurological, psychological, and social factors and their feedback loops.

Neurological Factors

Because the main risk factors for suicide are associated with depression and impulsivity (as well as past suicide attempts), it is difficult to identify neurological factors that uniquely contribute to suicide as distinct from factors that contribute to depression and impulsivity. Nevertheless, neurological factors that contribute to suicide per se are beginning to be identified.

150

Guided by the finding that mood disorders reflect, at least in part, levels of the neurotransmitter serotonin, Bielau and colleagues (2005) reported a suggestive trend: People who committed suicide tended to have fewer neurons in the part of the brain that produces serotonin than did people who died of other causes. In addition, researchers have found that people who commit suicide may have had fewer serotonin receptors in their brains (Boldrini et al., 2005). Notably, impulsivity is also associated with low serotonin levels.

Suicide seems to “run in families” (Correa et al., 2004), but it is difficult to discern a specific role of genes in influencing people to commit suicide. Depression has a genetic component, which may account for the higher rates of suicide among both twins in monozygotic pairs (13%) compared to dizygotic pairs (<1%) (Zalsman et al., 2002).

Psychological Factors: Hopelessness and Impulsivity

A number of the risk factors in TABLE 5.11 are psychological factors, such as poor coping skills (e.g., behaving impulsively) and poor problem-solving skills (e.g., difficulty identifying obstacles that interfere with meeting goals or failing to develop ways to work around obstacles), distorted and rigid thinking (thought patterns associated with depression), and hopelessness. Hopelessness, with its bleak thoughts of the future, is especially associated with suicide (Beck et al., 1985, 1990).

Social Factors: Alienation and Cultural Stress

Suicide rates vary across countries (De Leo, 2002a; Vijayakumar et al., 2005; WHO, 1999), which suggests that social and cultural factors affect these rates. In some developing countries, the presence or history of a psychological disorder poses less of a risk for suicide than it does in developed countries (Vijayakumar et al., 2005).

One important social factor that influences suicidal behavior is religion. Countries where the citizens are more religious tend to have lower suicide rates than do countries where citizens are less religious. Countries with a large Muslim population are among those with the lowest suicide rates in the world, followed by countries with a large Roman Catholic population; the tenets of both of these religions forbid suicide (De Leo, 2002a; Simpson & Conklin, 1989).

Feedback Loops in Understanding Suicide

ONLINE

Suicide can best be understood as arising from the confluence of neurological, psychological, and social factors. A neurological vulnerability, such as abnormal neurotransmitter functioning, serves as the backdrop. Add to that the psychological factors: depression or feelings of hopelessness, beliefs about suicide, poor coping skills, and perhaps impulsive or violent personality traits. In turn, these factors affect, and are affected by, social and cultural forces—such as economic realities, wars, cultural beliefs and norms about suicide, religion, stressful life events, and social support. The dynamic balance among all these factors can influence a person’s suicidal ideation, plans, and behavior (Sánchez, 2001; Wenzel et al., 2009).

151

Preventing Suicide

Suicide prevention efforts can focus on immediate safety or longer-term prevention.

Crisis Intervention

For a person who is actively suicidal, the first aim of suicide prevention is to make sure that the person is safe. After this, crisis intervention helps the person see past the hopelessness and rigidity that pervades his or her thinking, identifies whatever stressors have brought the person to this point, helps him or her develop new solutions to the problems, and enhances his or her ability to cope.

In addition, a clinician tries to discover whether the person is depressed or abusing substances; if so, these problems, which may lead to suicidal thoughts or behaviors, should be treated (Reifman & Windle, 1995). Because most people who die by suicide had untreated depression, treatment for depression that targets psychological factors—typically CBT—can play a key role in suicide prevention. Medications may also be prescribed to reduce depressive symptoms.

Long-Term Prevention

Ideally, long-term prevention programs decrease risk factors and increase protective factors, which should decrease the suicide rate. Thus, programs to prevent child abuse, to provide affordable access to mental health care (and so make it easier to obtain treatment for psychological disorders, in particular depression), to decrease substance abuse, and to increase employment may all help prevent suicides in the long term.

Part of the national suicide prevention plan in the United States is to increase awareness about suicide (Satcher, 1999), both among people who may feel suicidal and among the friends and family of someone feeling suicidal. The hope is that suicidal people will receive appropriate help before they commit suicide (see TABLE 5.12).

What can you do if someone you know seems to be suicidal? According to the National Institute of Mental Health (Goldsmith et al., 2002):

If you, or someone you know, are at risk for suicide, the following organizations can help:

|

152

Thinking Like A Clinician

Based on what you have learned about suicide, explain Kay Jamison’s suicide attempt in terms of the three types of factors. Identify how the neurological, psychological and social factors might have influenced each other via feedback loops. From what you know of her, what were Jamison’s risk and protective factors?