6.1 Common Features of Anxiety Disorders

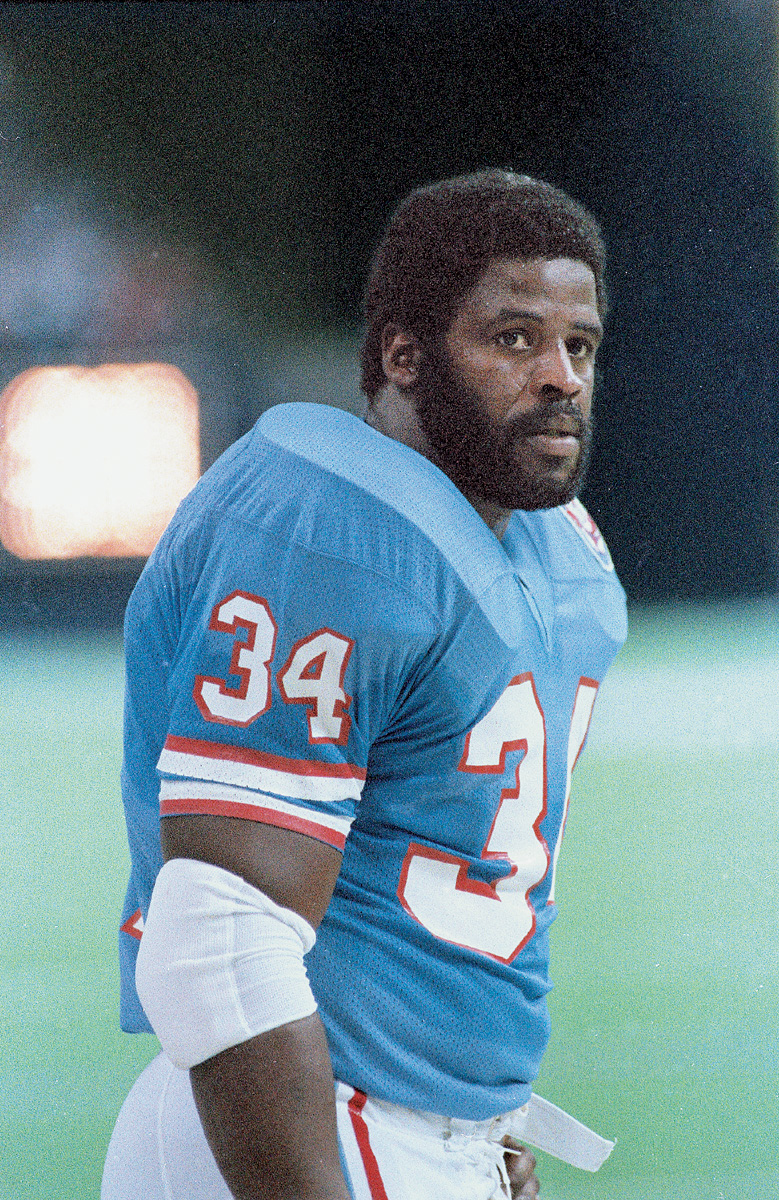

Earl Campbell played high school football and, after graduating, became a star running back on the University of Texas–Austin football team. From there, he went on to play for the Houston Oilers in the NFL. At age 24, he married Reuna, a woman from his hometown whom he had been dating for 10 years. Five years later, they had their first child, and 2 years after that, at the age of 31, Campbell retired from football.

156

Campbell went on to work for the University of Texas–Austin as a goodwill ambassador, representing the school at various functions, and helping student-athletes commit to their studies. One day, as Campbell was driving from Austin to Dallas, he stopped at a traffic light and had an unusual experience:

Out of the blue, my heart started racing. I felt my chest. Then I broke into a cold sweat, began hyperventilating, and became convinced I was having a heart attack. The people in the car next to mine seemed totally unaware that anything was wrong. My heart just kept racing. I couldn’t stop it. I was going to die. How could I stop it? It was getting worse. I was dying! The driver behind me started blowing his horn. The light had turned green. I needed help. I couldn’t get out of the car. “God help me!” I prayed. Then it stopped—just like that, my heart stopped racing. I put my hand to my heart again. It felt normal. My hands and arms were covered with a cold clammy sweat. I wiped the perspiration from my face and look[ed] at myself in the rearview mirror. For the first time in my life, I caught sight of a frightened Earl Campbell and I didn’t like it….

(Campbell & Ruane, 1999, pp. 83–84)

Not only did Campbell have frightening bodily sensations, but he also developed worries about “the little details that most people don’t even think about. They weigh on me and tie up my mind. I am continually inundated with intrusive thoughts related to everything I say or do. Do I look okay? Am I walking right? Did I do this right? That right? Why is everyone looking at me? Is it because I’m Earl Campbell, or is it because there’s something wrong with me?” (Campbell & Ruane, 1999, p. 199). Campbell’s experiences involve anxiety.

What Is Anxiety?

Anxiety A sense of agitation or nervousness, which is often focused on an upcoming possible danger.

Like the term depression, the words anxiety and anxious are used in everyday speech. But what do mental health professionals and researchers mean when they use these terms? Anxiety refers to a sense of agitation or nervousness, which is often focused on an upcoming potential danger.

We all feel afraid and anxious from time to time. These feelings can be adaptive, signaling the presence of a dangerous stimulus, which in turn leads us to be more alert—which then heightens our senses. For instance, if you are walking alone down a dark, quiet street late at night, you might feel anxious, which makes you alert; you might then be able to hear particularly well or be more sensitive to another person’s presence behind you. Such heightened senses can be adaptive on a dark street. Should you hear or sense someone, you may choose to head quickly to a well-lit and busier street. Similarly, a moderate level of anxiety before a test or presentation can enhance your performance (Deshpande & Kawane, 1982)—and, in fact, the absence of anxiety can lead to lackluster performance, even if you know the material well. Thus, feeling afraid or anxious can be normal and adaptive.

Anxiety disorder A category of psychological disorders in which the primary symptoms involve fear, extreme anxiety, intense arousal, and/or extreme attempts to avoid stimuli that lead to fear and anxiety.

Extreme anxiety, however, is a persistent, vague sense of dread or foreboding even when not in the presence of a feared stimulus (such as a snake or a plane trip). An anxiety disorder involves fear, extreme anxiety, intense arousal, and extreme attempts to avoid stimuli that lead to fear and anxiety. These emotions, or the efforts to avoid experiencing them, can create a high level of distress, which can interfere with normal functioning.

The Fight-or-Flight Response Gone Awry

Fight-or-flight response The automatic neurological and bodily response to a perceived threat; also called the stress response.

Campbell describes some of the frightening physical sensations he experienced in this way: “Visualize yourself just sitting back in a chair, relaxing. Suddenly, your heart starts racing as if you had just run a hundred-yard dash. You break into a cold sweat. You have trouble breathing. You feel there is nothing you can do to stop all of these things from happening” (Campbell & Ruane, 1999, p. i). Campbell was describing the effects of the fight-or-flight response, also called the stress response (see Chapter 2), which occurs when a person perceives a threat. Suppose you think you see a mugger lurking on a dark doorstep as you are hurrying home, alone, late at night. Your brain and body respond as if you must either fight or take flight, primarily by activating the sympathetic branch of the autonomic nervous system. The stress response prepares your body to exert physical energy for an action, either fighting the threat or running away from it. It does not matter whether there is an actual threat. Your body automatically responds because you perceive a threat. Your body responds in a number of ways, most notably by:

157

- increasing your heart rate and breathing rate (in order to provide more oxygen to your muscles and brain),

- increasing the sweat on your palms (a small amount, which helps you grip better—yet not so much as to make your palms become slippery), and

- dilating your pupils (in order to let in more light and help you to see better).

Your body responds this way even to threats that do not require a lot of physical energy, such as—for many people—speaking in front of a group (or even thinking about speaking in front of them) or taking a pop quiz. In such cases, your body gets prepared, but most of the physical preparations aren’t really necessary.

Panic An extreme sense (or fear) of imminent doom, together with an extreme stress response.

This fight-or-flight (stress) response underlies the fear and anxiety involved in almost all anxiety disorders. Some people have an overactive stress response—they have higher levels of arousal during this response. Other people may not have an overactive stress response, but they may misinterpret their arousal during this response and attribute the bodily sensations to a physical ailment. They might, for instance, interpret an increased heart rate as a heart attack. In either case, some people come to feel afraid or anxious about the physical sensations of the fight-or-flight response or the conditions that seem to have caused it. When their arousal feels as if it is getting out of control, they may start to feel panic, which is an extreme sense (or fear) of imminent doom, together with an extreme stress response (Bouton et al., 2001)—what Campbell experienced sitting in his car at a stoplight. Some people who become panicked develop a phobia, which is an exaggerated fear of an object or a situation, together with an extreme avoidance of that object or situation. Such avoidance can interfere with everyday life. For instance, at one point, Campbell avoided crowded rooms because he thought that they might bring on the uncomfortable physical sensations he’d experienced.

Phobia An exaggerated fear of an object or a situation, together with an extreme avoidance of the object or situation.

Significant anxiety and phobias are not unusual or rare. In the United States, anxiety disorders are the most common kind of mental disorder (Barlow, 2002a); approximately 15% of people will have some type of anxiety disorder in their lifetimes (Somers et al., 2006). Women are twice as likely as men to be diagnosed with an anxiety disorder (Somers et al., 2006). Some explanations of this gender difference rest on biological factors, such as the hormonal shifts that occur during a woman’s childbearing years (Ginsberg, 2004); the possible role of hormones is consistent with the fact that the gender difference in anxiety disorders coincides with the onset of puberty (as is the case with depression; see Chapter 5). Other explanations for the gender difference rest on cultural factors (Pigott, 1999): Unlike Campbell, many men tend to be reluctant to acknowledge symptoms of anxiety because they fear that admitting such feelings might undercut the masculine image they project to others.

Comorbidity of Anxiety Disorders

As you’ll see throughout this text, symptoms of anxiety or avoidance may occur in many psychological disorders, including mood disorders (Chapter 5), body dysmorphic disorder (Chapter 7), and anorexia nervosa (Chapter 10). Clinicians must determine whether the anxiety and avoidance symptoms are the primary cause of the disturbance or a by-product of another type of problem. In the case of anorexia nervosa, for example, when someone gets anxious about eating high-calorie foods, the anxiety is secondary to larger concerns about food, weight, and appearance.

158

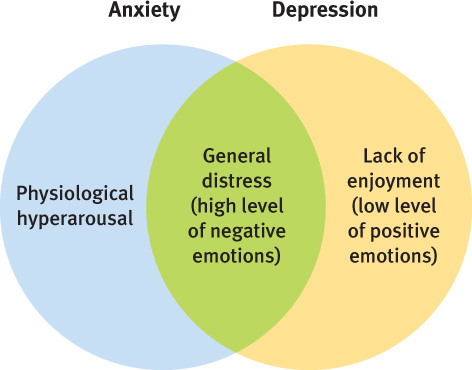

Anxiety and depression often occur together; approximately 50% of people with an anxiety disorder are also depressed (Brown et al., 2001). Researchers and clinicians are trying to discover why there is such high comorbidity between anxiety disorders and depression. Some researchers have proposed a three-part model of anxiety and depression that specifies the ways in which the two kinds of disorders overlap and the ways in which they are distinct (Clark & Watson, 1991; Mineka, Watson, & Clark, 1998). This model has been supported by research (Joiner, 1996; Olino et al., 2008). The three parts of the model are depicted in Figure 6.1. Another disorder that commonly co-occurs with an anxiety disorder is substance use disorder, and approximately 10–25% of people who have anxiety disorders also abuse alcohol (Bibb & Chambless, 1986; Otto et al., 1992).

Thinking Like A Clinician

What is the difference between fear and anxiety? Why (or when) might the fight-or-flight response become a problem? If people can have symptoms of anxiety when they have other types of disorders, what determines whether an anxiety disorder should be the diagnosis?