6.3 Panic Disorder and Agoraphobia

Earl Campbell’s uncomfortable episodes of anxiety didn’t stop:

The second night we were in the [new] house, I had my third episode. It felt just like the second one had. I was lying in bed watching television, and Reuna was sound asleep next to me. I was trying to relax and not think about my problem, but my problem was all I could think about. All of a sudden, my heart went crazy—pounding, pounding harder and harder. I thought it was going to leap right out of my chest. I sat up, struggling to regain my composure. It got worse. I couldn’t breathe again.

Panic attack A specific period of intense fear or discomfort, accompanied by physical symptoms, such as a pounding heart, shortness of breath, shakiness, and sweating, or cognitive symptoms, such as a fear of losing control.

(Campbell & Ruane, 1999, p. 92)

Campbell again thought he was having a heart attack and that his life was ending. He was not; instead, Campbell was having a panic attack. A panic attack is a specific period of intense fear or discomfort, accompanied by physical symptoms, such as a pounding heart, shortness of breath, shakiness, and sweating, or cognitive symptoms, such as a fear of losing control.

The Panic Attack—A Key Ingredient of Panic Disorder

Some of the physical symptoms of a panic attack may resemble those associated with a heart attack—heart palpitations, shortness of breath, chest pain, and a feeling of choking or being smothered (see TABLE 6.3), which is why Earl Campbell mistook his panic attacks for heart attacks. In fact, emergency room staff have learned to look for evidence of a panic attack when a patient who purportedly has had a heart attack arrives. During a panic attack, the symptoms generally begin quickly, peak after a few minutes, and disappear within an hour.

A discrete period of intense fear or discomfort, in which at least four of the following symptoms develop abruptly and reach a peak within minutes:

|

| Reprinted with permission from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, (Copyright ©2013). American Psychiatric Association. All Rights Reserved. |

In some cases, panic attacks are cued—that is, associated with particular objects, situations, or sensations. Although panic attacks are occasionally cued by a particular external stimulus (such as seeing a snake), they are more frequently cued by situations that are associated with internal sensations similar to panic, such as breaking out into a sweat (when overheated). In other cases, panic attacks are uncued—that is, spontaneous and feel as though they come out of the blue—and are not associated with a particular object or situation. Panic attacks can occur at any time, even while sleeping (referred to as nocturnal panic attacks, which Campbell experienced). Infrequent panic attacks are not unusual; they affect 30% of adults at some point in their lives.

Recurrent panic attacks may interfere with daily life (for example, if they occur on a bus or at work) and may cause the person to leave the situation to return home or seek medical help. The symptoms of a panic attack are so unpleasant that people who suffer from this disorder may try to prevent another attack by avoiding environments and activities that increase their heart rates (hot places, crowded rooms, elevators, exercise, sex, mass transportation, or sporting events). They might even avoid leaving home (Bouton et al., 2001).

166

What Is Panic Disorder?

Campbell describes panic disorder: “…the fear of having another panic attack, because the last thing in the world you want to face is one more of those horrible, frightening experiences. And the last thing you want to accept is the idea of living the rest of your life with panic. This condition caused me to shut myself up in the my house, where I would sit in the dark, frustrated, crying, afraid to go out. At one point, I even considered suicide” (Campbell & Ruane, 1999, p. ii).

Panic disorder An anxiety disorder characterized by frequent, unexpected panic attacks, along with fear of further attacks and possible restrictions of behavior in order to prevent such attacks.

To mental health clinicians, panic disorder is marked by frequent, unexpected panic attacks, along with worry about further attacks or their consequences (such as potentially losing control) and restrictions of behavior in order to prevent such attacks, lasting at least 1 month (see TABLE 6.4). Note, however, that having panic attacks doesn’t necessarily indicate a panic disorder. Panic attacks are distinguished from panic disorder by the frequency and unpredictability of the attacks and the person’s reaction to the attacks. Research suggests that among people with panic disorder, panic attacks aren’t as out of the blue as they feel: Changes in breathing and heart rate occur over 30 minutes before the onset of a panic attack (Meuret et al., 2011). TABLE 6.5 lists additional facts about panic disorder, and Case 6.2 provides a glimpse of a woman who suffers from panic attacks.

|

| Reprinted with permission from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, (Copyright ©2013). American Psychiatric Association. All Rights Reserved. |

| Prevalence |

|

| Comorbidity |

|

| Onset |

|

| Course |

|

| Gender Differences |

|

| Cultural Differences |

|

| Source: Unless otherwise noted, information in the table is from American Psychiatric Association, 2013. |

CASE 6.2 • FROM THE OUTSIDE: Panic Disorder

S was a 28-year-old married woman with two children, aged 3 and 5 years. S had experienced her first panic attack approximately 1 year prior to the time of the initial assessment. Her father had died 3 months before her first panic attack; his death was unexpected, the result of a stroke. In addition to grieving for her father, S became extremely concerned about the possibility of herself having a stroke. S reported [that before her father’s death, she’d never had a panic attack nor been concerned about her health.] Apparently, the loss of her father produced an abrupt change in the focus of her attention, and a cycle of anxiety began [which led to a heightened] awareness of the imminence of her own death, given that “nothing in life was predictable.”…S became increasingly aware of different bodily sensations. Following her first panic attack, S was highly vigilant for tingling sensations in her scalp, pain around her eyes, and numbness in her arms and legs. She interpreted all of these symptoms as indicative of impending stroke. Moreover, because her concerns became more generalized, she began to fear any signs of impending panic, such as shortness of breath and palpitations.

Her concerns led to significant changes in her lifestyle [and she avoided] unstructured time in the event she might dwell on “how she felt” and, by so doing, panic…. S felt that her life revolved around preventing the experience of panic and stroke.

(Craske et al., 2000, pp. 45–46)

167

Symptoms of panic disorder are similar across cultures, but in some cultures the symptoms focus on fear of magic or witchcraft (American Psychiatric Association, 2000); in other cultures, the physical symptoms may be expressed differently. For example, among Cambodian refugees, symptoms of panic disorder include a fear that “wind-and-blood pressure” (referred to as wind overload) may increase to the point of bursting the neck area, and patients may complain of a sore neck, along with headache, blurry vision, and dizziness (Hinton et al., 2001).

In some cultures, people experience symptoms that are similar—but not identical—to the classic symptoms of a panic attack. In the Caribbean, Puerto Rico, and some areas of Latin America, an anxiety-related problem called ataque de nervios can occur, usually in women. The most common symptoms are uncontrollable screaming and crying attacks, together with palpitations, shaking, and numbness. An ataque de nervios differs from a panic attack not only in the specific symptoms experienced but also because it usually is triggered by a specific upsetting event, such as a funeral or a family conflict. Panic attacks that are part of panic disorder tend not to have such an obvious situational trigger. Furthermore, people who have had an ataque de nervios are usually not worried about recurrences (Guarnaccia, 1997b; Salmán et al., 1997).

Panic disorder, as well as ataque de nervios and other anxiety disorders, is diagnosed at least twice as often in women as in men (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). A cultural explanation for this gender difference is that men may be less likely to report symptoms of anxiety or panic because they perceive them as inconsistent with how men are “supposed” to behave in their culture (Ginsburg & Silverman, 2000).

In short, panic disorder has a core of common symptoms across the world, centering on frequent, unexpected panic attacks and fear of further attacks, but culture does affect the specifics.

What Is Agoraphobia?

After Campbell’s first panic attack, he refused to go out:

I knew I could not set foot outside my house. Until I learned what was wrong with me, the only place I would go was to a doctor’s office or a hospital…. Reuna thought that was part of my problem. I was shutting myself off from the world…. What if I had another attack? What if it happened while I was in church? Or while I was walking down the aisle of a crowded grocery store? What would I do? How could I deal with the humiliation that such a loss of control would bring?

(Campbell & Ruane, 1999, pp. 93–94)

Campbell had developed agoraphobia.

Agoraphobia An anxiety disorder characterized by persistent avoidance of situations that might trigger panic symptoms or from which help would be difficult to obtain.

Agoraphobia (which literally means “fear of the marketplace”) refers to the persistent avoidance of situations that might trigger panic symptoms or from which escape would be difficult or help would not be available. For these reasons, public transportation, tunnels, bridges, crowded places, or even being home alone are typically avoided or entered with difficulty by people with agoraphobia.

168

About half of the people with agoraphobia also have panic disorder, and most of the other half experience panic symptoms (but the symptoms are not strong or frequent enough to meet the criteria for panic disorder); a patient with agoraphobia can also be diagnosed with panic disorder if he or she has symptoms that meet the criteria for panic disorder. The avoidance that is a part of agoraphobia is typically a (maladaptive) attempt not to enter situations that could lead to panic symptoms. These people avoid situations in which they fear they might panic or lose control of themselves. However, people who only avoid particular kinds of stimuli (only bridges or only parties) are not diagnosed with agoraphobia, which is a more general pattern of avoiding many kinds of environments or situations. TABLE 6.6 lists the criteria for agoraphobia. TABLE 6.7 lists additional facts about agoraphobia, Shirley B., in Case 6.3, suffered from symptoms of agoraphobia.

|

| Reprinted with permission from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, (Copyright ©2013). American Psychiatric Association. All Rights Reserved. |

| Prevalence |

|

| Comorbidity |

|

| Onset |

|

| Course |

|

| Gender Differences |

|

| Cultural Differences |

|

| Source: Unless otherwise noted, information in the table is from American Psychiatric Association, 2013. |

CASE 6.3 • FROM THE OUTSIDE: Agoraphobia

“The Story of an Agoraphobic” by Shirley B.:

There isn’t much I can say about how I became agoraphobic. I just slipped a little day by day…. My daughter Nadeen was always by my side on those rare occasions when I ventured outside, forced to leave my home when I needed medical attention. In the past my fear kept me at home with all sorts of physical pains and ailments, as horrific as the pain was, the pain of facing the outside world was greater. When I had two abscessed teeth and my jaw was swollen to twice its normal size I was in such excruciating pain that I had to go to the dentist. So with my legs wobbling, my heart pounding, my hands sweating, and my throat choking, to the dentist I went. After examining my x-rays, the dentist said he wouldn’t be able to do anything with my teeth because they were so infected, he prescribed medication for the pain and infection and said that I must return in ten days, not in two years. I felt as though those ten days were a countdown to my own execution. Each day passed at lightning speed—like a clock ticking away. The fear grew stronger and stronger. I had to walk around with my hand on my heart to keep it from jumping so hard, as if I were pledging allegiance, which I was—to my fears and phobia. I asked God to please give me strength to go back to the dentist. When the day came, I knew that my preparations would take me a little over four hours. I had to leave time, not just to bathe and dress, but to debate with myself about going.

(Anxiety Disorders Association of America)

People with extreme agoraphobia cannot function normally in daily life. Some are totally housebound, too crippled by anxiety and fear to go to work, the supermarket, or the doctor. Others with agoraphobia are able to function better than Shirley B. and can enter many situations without triggering panic or marked fear or anxiety. Relying on a friend or family member, often referred to as a “safe” person (for Shirley it was her daughter Nadeen), can help the sufferer enter feared situations that otherwise might be avoided.

People with agoraphobia who also have panic symptoms or panic attacks avoid situations that are associated with past panic; thus, they do not have the opportunity to learn that they can be in such situations and not have a panic attack.

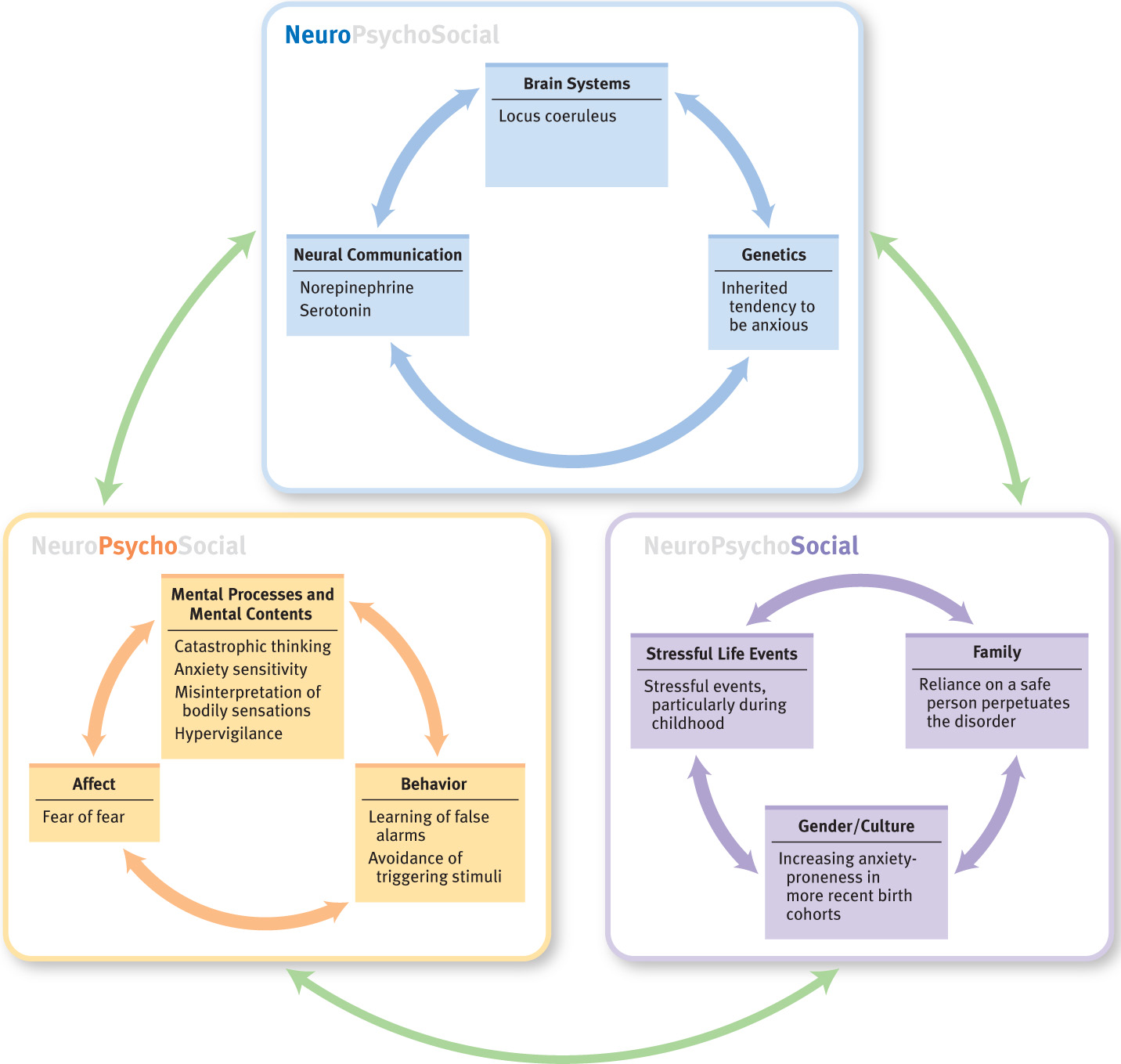

Understanding Panic Disorder and Agoraphobia

“I still don’t know what triggers a panic attack, but I can tell anyone reading this who has never experienced one that it is a devastating experience…. An attack may hit me on a day when I’m feeling relaxed and happy. That’s when I think, ‘Why me?’ ‘Why today?’” (Campbell & Ruane, 1999, p. 151). The neuropsychosocial approach allows us to address Campbell’s question about why panic disorder and agoraphobia occur and are maintained. Because agoraphobia typically develops as a way to avoid panic symptoms, in what follows we will focus more on panic disorder. Each type of factor makes an important and unique contribution.

169

Neurological Factors

Brain systems, neural communication, and genetics contribute to panic disorder and agoraphobia. Specifically, these three types of neurological factors appear to give rise to a heightened sensitivity to breathing changes.

Brain Systems

One key to explaining panic attacks came after researchers discovered that they could induce such attacks in the laboratory. Patients who had had panic attacks volunteered to hyperventilate (that is, to breathe in rapid, short pants, decreasing carbon dioxide levels in the blood), which triggered panic attacks. Moreover, researchers found that injections of some medically safe substances, such as sodium lactate (a salt produced in sweat) and caffeine, also produced attacks—but only in people who have panic disorder (Nutt & Lawson, 1992; Pitts & McClure, 1967). Why do these substances induce panic attacks? One possibility is that the brains of people who experience panic attacks have a low threshold for detecting decreased oxygen in the blood, which triggers a brain mechanism that warns us when we are suffocating (Beck et al., 1999; Papp et al., 1993, 1997). As predicted by this theory, patients with panic disorder cannot hold their breath as long as control participants can (Asmundson & Stein, 1994). When triggered, the neural mechanism not only produces panic but also leads to hyperventilation and a strong sense of needing to escape.

Neural Communication

Researchers also have been investigating the role of neurotransmitters in giving rise to panic disorder. One key neurotransmitter is norepinephrine, too much of which is apparently produced in people who have anxiety disorders (Nutt & Lawson, 1992). The locus coeruleus is a small structure in the brainstem that produces norepinephrine, and some researchers have theorized that it is too sensitive in people with panic disorder (Gorman et al., 1989)—and thus may produce too much norepinephrine. The locus coeruleus and norepinephrine are important because they are central to the body’s “alarm system,” which causes the fight-or-flight response (including faster breathing, increased heart rate, and sweating), which often occurs at times of panic.

Finally, we note that SSRIs can reduce the frequency and intensity of panic attacks (DeVane, 1997); SSRIs reduce the effects of serotonin, which affects the locus coeruleus in complex ways (Bell & Nutt, 1998).

Genetics

Concordance rate The probability that both twins will have a characteristic or disorder, given that one of them has it.

Genetic factors appear to play a role in the emergence of panic disorder. In fact, first-degree biological relatives of people with panic disorder are up to eight times more likely to develop the disorder than are control participants, and up to 20 times more likely to do so if the relative developed it before 20 years of age (Crowe et al., 1983; Torgersen, 1983; van den Heuvel et al., 2000). Twin studies have yielded similar results by examining concordance rates; a concordance rate is the probability that both twins will have a characteristic or disorder, given that one of them has it. The concordance rate in pairs of female identical (monozygotic) twins is approximately 24%, in contrast to 11% for pairs of fraternal (dizygotic) twins (Kendler et al., 1993). Thus, the more genes in common, the higher the concordance rates.

170

Psychological Factors

Not all cases of panic disorder are related to a person’s threshold for detecting suffocation; some cases of panic disorder arise from learning. Thus, behavioral and cognitive theories can also help us understand how panic disorder and agoraphobia arise and are perpetuated: People come to associate certain stimuli with the sensations of panic and then develop maladaptive beliefs and behaviors with regard to those stimuli and the sensations that are related to anxiety and panic.

Learning: An Alarm Going Off

Learning theory offers one possible explanation for at least some cases of panic disorder. Initially, a person may have had a first panic attack in response to a stressful or dangerous life event (a true alarm). This experience produces conditioning, whereby the initial bodily sensations of panic (such as increased heart rate or sweaty palms) become false alarms associated with panic attacks. As the normal sensations that are part of the fight-or-flight response come to be associated with subsequent panic attacks, the bodily sensations of arousal themselves come to elicit panic attacks (learned alarms). The person then develops a fear of fear—a fear that the arousal symptoms of fear will lead to a panic attack (Goldstein & Chambless, 1978), much as S did in Case 6.2. After developing this fear of fear, the person tries to avoid behaviors or situations where such sensations might occur (Mowrer, 1947; White & Barlow, 2002).

Cognitive Explanations: Catastrophic Thinking and Anxiety Sensitivity

Cognitive theories, which focus on how a person interprets and then responds to alarm signals from the body, offer other possible reasons why panic disorder could arise. People with panic disorder may misinterpret normal bodily sensations as indicating catastrophic effects (Salkovskis, 1988), which is referred to as catastrophic thinking. Catastrophic thinking can arise in part from anxiety sensitivity, which is a tendency to fear bodily sensations that are related to anxiety along with the belief that such sensations indicate that harmful consequences will follow (McNally, 1994; Reiss, 1991; Schmidt et al., 1997). For example, a person with high anxiety sensitivity is likely to believe—or fear—that an irregular heartbeat indicates a heart problem or that shortness of breath signals being suffocated. People with high anxiety sensitivity tend to know what has caused their bodily symptoms—for instance, that exercise caused a faster heart rate—but they become afraid anyway, believing that danger is indicated, even if it is not an immediate danger (Bouton et al., 2001; Brown et al., 2003).

Social Factors: Stressors, a Sign of the Times, and “Safe People”

Evidence suggests that social stressors contribute to panic disorder: People with panic disorder tend to have had a higher-than-average number of such stressful events during childhood and adolescence (Horesh et al., 1997). Moreover, 80% of people with panic disorder reported that the disorder developed after a stressful life event.

In addition, cultural factors can influence whether people develop panic disorder, perhaps through culture’s influence on personality traits. For example, over the past five decades, increasing numbers of Americans have developed the personality trait of anxiety-proneness (Spielberger & Rickman, 1990). The average child today scores higher on measures of this trait than did children who received psychiatric diagnoses in the 1950s (Twenge, 2000)! The higher baseline level of anxiety in the United States may be a result of greater dangers in the environment—such as higher crime rates, new threats of terrorism, and new concerns about food safety—or greater media exposure of such dangers.

171

Social factors are also often related to the ways patients cope with agoraphobia. As with GAD, the presence of a close relative or friend—a “safe person” or companion—can help the patient temporarily cope with agoraphobia. In this case, the presence of a safe person can decrease catastrophic thinking and panicking, as well as the sufferer’s arousal. Although a safe person can make it possible for the patient with agoraphobia to go into situations that he or she wouldn’t enter alone, reliance on a safe person can end up perpetuating the disorder: By venturing into anxiety-inducing situations only when a safe person is around, the patient never habituates to the anxiety symptoms experienced when alone and in the situation.

Feedback Loops in Understanding Panic Disorder and Agoraphobia

Cognitive explanations of panic disorder can help show how a few panic attacks can progress to panic disorder, but not everyone who has panic attacks develops panic disorder. It is only when neurological and psychological factors interact with bodily states that panic disorder develops (Bouton et al., 2001). For example, a man’s argument with his wife (social factor) might arouse his anger and increase his breathing rate. Breathing faster results in a lower carbon dioxide level in the blood, which then leads the blood vessels to constrict—which means less oxygen throughout the brain and body (neurological factor); the ensuing physical sensations (such as light-headedness) may be misinterpreted (psychological factor) as the early stages of suffocation, leading the man to panic (Coplan et al., 1998). This is how such physical changes can serve as a false alarm (Beck, 1976). After many false alarms, the associated sensations may become learned alarms and trigger panic in the absence of a social stressor (Barlow, 1988). Also, this man may become hypervigilant for alarm signals of panic attacks, leading to anticipatory anxiety. In turn, this anxiety increases activity in his sympathetic nervous system, which causes the breathing and heart rate changes that he feared. In this way, the man may trigger his own panic attack. Figure 6.3 illustrates these three factors and their feedback loops.

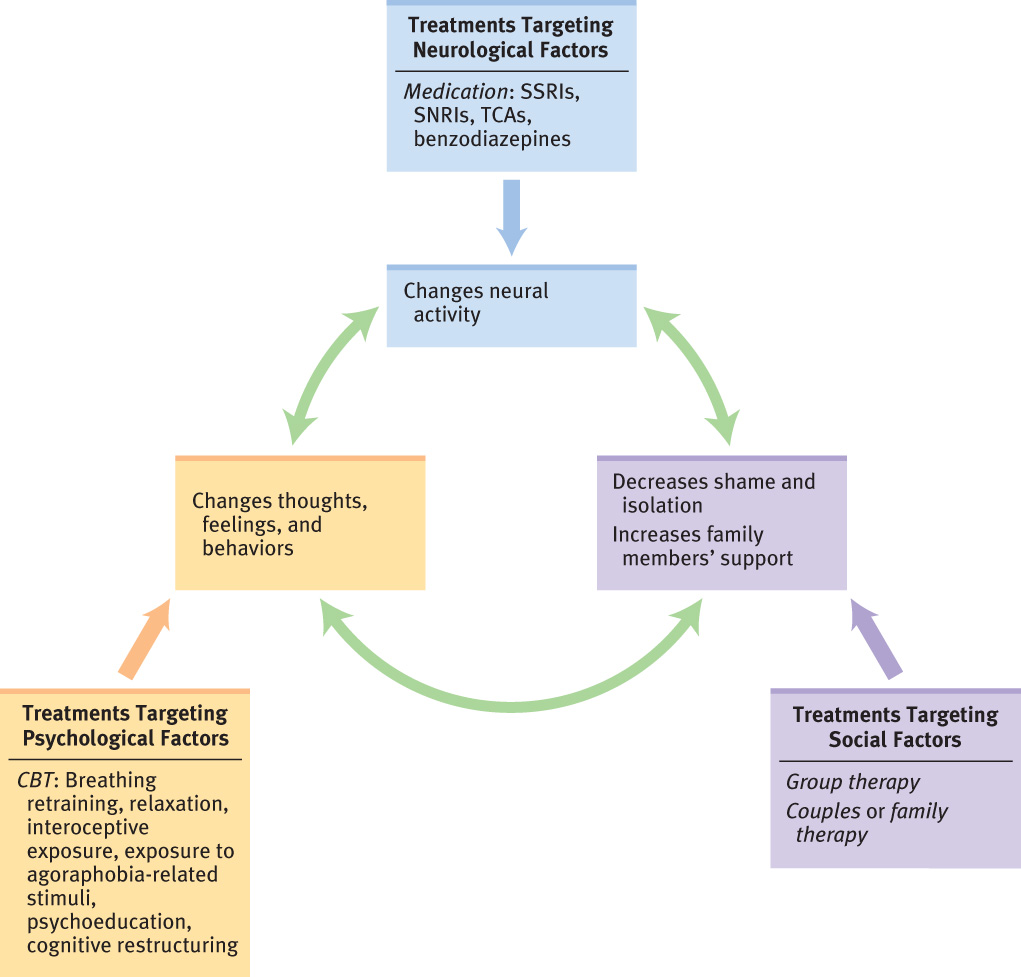

Treating Panic Disorder and Agoraphobia

Earl Campbell received treatment for his panic disorder—medication, cognitive-behavior therapy (CBT), and social support—which targeted all three types of neuropsychosocial factors. Treatment for agoraphobia also addresses panic symptoms because fear of having panic symptoms drives sufferers to narrow their lives.

Targeting Neurological Factors: Medication

To treat panic disorder, a psychiatrist or another type of health care provider licensed to prescribe medication may recommend an antidepressant or a benzodiazepine. Benzodiazepines are prescribed as a short-term remedy; the benzodiazepines alprazolam (Xanax) and clonazepam (Klonapin) affect the targeted symptoms within 36 hours, and they need not be taken regularly. One of these drugs might be prescribed during a short but especially stressful period. Side effects of benzodiazepines include drowsiness and slowed reaction times, and patients can suffer withdrawal or need to take increasingly larger doses when these drugs are taken for an extended period of time. For these reasons, antidepressants such as an SNRI, an SSRI, or TCAs (tricyclic antidepressants), such as clomipramine (Anafranil), are better long-term medications and are now considered “first-line” medications for panic disorder (Batelaan et al., 2012). However, these medications can take up to 10 days to have an effect (Kasper & Resinger, 2001). After Campbell’s panic attacks were diagnosed, he initially relied on such medications as his sole treatment; like most people, though, when he stopped taking the medication or forgot to take a pill, his symptoms returned. Such recurrences motivated him to make use of other types of treatments.

172

Targeting Psychological Factors

CBT is the first-line treatment for panic disorder because it has the most enduring beneficial effects of any treatment (Cloos, 2005; DiMauro et al., 2013). Effective CBT methods can emphasize either the behavioral or the cognitive aspects of change.

173

Behavioral Methods: Relaxation Training, Breathing Retraining, and Exposure

For people with panic disorder, any bodily arousal can lead to a fight-or-flight response. Therapists may teach patients breathing retraining and relaxation techniques, which stop the progression from bodily arousal to panic attack and increase a sense of control over bodily sensations. Campbell reported how he learned to take “long deep breaths and relax my body completely when panic struck…. I somehow had to convince myself that the attack was not really happening. I had to fight it off by relaxing myself” (Campbell & Ruane, 1999, p. 119).

Other behavioral methods include exposure. To decrease a patient’s reaction to bodily sensations associated with panic, behavioral therapists may use interoceptive exposure: They have the patient intentionally elicit the bodily sensations associated with panic so that he or she can habituate to those sensations and not respond with fear. During exposure to interoceptive cues, patients are asked to behave in ways that induce the long-feared sensation, such as spinning around to the point of dizziness or intentionally hyperventilating (see TABLE 6.8 for a more extensive list). Within approximately 30 minutes, the bodily arousal subsides. This procedure allows patients to learn that the bodily sensations pass and no harm befalls them. For people with agoraphobia symptoms, exposure addresses the patient’s tendency to avoid activities and situations associated with panic attacks (such as exercise or crowded theaters, respectively).

Interoceptive exposure A behavioral therapy method in which patients intentionally elicit the bodily sensations associated with panic so that they can habituate to those sensations and not respond with fear.

| Exercise | Duration (seconds) | Sensation intensity (0–8) | Anxiety (0–8) | Similarity (0–8) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shake head from side to side | 30 | |||

| Place head between legs and then lift | 30 | |||

| Run on spot | 60 | |||

| Hold breath | 30, or as long as possible | |||

| Completely tense body muscles | 60, or as long as possible | |||

| Spin in swivel chair | 60 | |||

| Hyperventilate | 60 | |||

| Breathe through narrow straw | 120 | |||

| Stare at spot on wall or own mirror image | 90 | |||

| Source: Craske & Barlow, 1993, Table 1.4, p. 36. For more information see the Permissions section. | ||||

Cognitive Methods: Psychoeducation and Cognitive Restructuring

Cognitive methods for panic disorder help the patient recognize misappraisals of bodily symptoms and learn to correct mistaken inferences about such symptoms. First, psychoeducation for people with panic disorder involves helping them understand both how their physical sensations are symptoms of panic—not of a heart attack or some other harmful medical situation—and the role of catastrophic thinking. Campbell read a pamphlet about panic disorder that described his symptoms perfectly. Having learned about the disorder in this way, he was better able to handle future panic attacks: “One of the most important things I have learned about my panic disorder over the years is that although my heart may be racing and I may feel like I’m having a heart attack, I know that I’m not. And I know it’s going to stop” (Campbell & Ruane, 1999, p. 204).

174

Second, cognitive restructuring is then used to transform the patient’s initial frightened thoughts of a medical crisis into more realistic thoughts, identifying the symptoms of panic, which may be uncomfortable but do not indicate danger (Beck et al., 1979). For instance, a therapist may help a patient identify the automatic negative thought about bodily arousal (“I won’t be able to breathe…I’ll pass out”) and then challenges the patient about the belief: Was the patient truly unable to breathe, or was breathing only difficult? Has the patient fainted before? In this way, each of the patient’s automatic negative thoughts related to panic sensations are challenged and thereby reduced. Learning to interpret correctly both internal and external events can play a key role in preventing panic attacks that occur when a person experiences symptoms of suffocation (Clark, 1986; Taylor & Rachman, 1994).

Targeting Social Factors: Group and Couples Therapy

Therapy groups (either self-help or conducted by a therapist) that focus specifically on panic disorder and agoraphobia can be a helpful component of a treatment program (Galassi et al., 2007). Meeting with others who have similar difficulties and sharing experiences can help to decrease a patient’s sense of isolation and shame. Moreover, couples therapy or family therapy may be appropriate when a partner or other family member has been the safe person; as the patient gets better, he or she may rely less on that person, which can affect their relationship. In some cases, the patient’s increasing independence is satisfying for everyone; but if the safe person has found satisfaction in tending to the patient, the patient’s increased independence can be a stressful transition for that person.

Feedback Loops in Treating Panic Disorder and Agoraphobia

Because agoraphobia frequently co-occurs with panic disorder, we discuss treatments for both here. Invariably, medication—which changes neurological functioning—stops being beneficial when the patient stops taking it. The positive changes in neural communication and brain activity and the associated changes in thoughts, feelings, and behaviors do not endure; the symptoms of panic disorder return. However, for some patients, medication is a valuable first step, providing enough relief from symptoms that these patients are motivated to obtain CBT, which can change their reactions (psychological factor) to perceived bodily sensations (neurological factor). When a patient receives both medication and CBT, the medication should be at a low enough dose that the patient can still feel the sensations that led to panic in the past (Taylor, 2000). In fact, the dose should be gradually decreased so that the patient can experience enough anxiety to be increasingly able to make use of cognitive-behavioral methods. It is the CBT that leads to enduring changes. Successful treatment will probably lead the patient, especially if he or she also has agoraphobia, to become more independent—which in turn can change the person’s relationships, particularly with their safe people (social factor). These factors and their feedback loops are summarized in Figure 6.4.

175

Thinking Like A Clinician

All you know about Fiona is that she has had about 10 panic attacks. Is this enough information to determine whether she has panic disorder? If it is, does she have the disorder? If this isn’t enough information, what else would you want to know, and why? Now suppose that Fiona starts missing Monday classes because of panic attacks on those days. She also stops going to parties on weekends because she had a couple of panic attacks at parties. Would you change or maintain your answer about whether she has panic disorder? Why or why not? Suppose Fiona does have panic disorder. Explain how she might have developed the disorder. By the end of the semester, Fiona no longer goes out of her apartment for fear of getting a panic attack. What might be appropriate treatments for Fiona?