6.5 Specific Phobia

Another type of anxiety disorder—one that does not seem to apply to Campbell—is specific phobia. To understand why this diagnosis would not apply to him, we need to learn what specific phobia is.

What Is Specific Phobia?

Specific phobia An anxiety disorder characterized by excessive or unreasonable anxiety about or fear related to a specific situation or object.

What distinguishes normal fear and avoidance of an object or situation from its “abnormal” counterpart? DSM-5 describes the central element of specific phobia as a marked anxiety or fear of a specific situation or object that is disproportional to the actual danger posed (see TABLE 6.11; American Psychiatric Association, 2013). A person with a specific phobia works hard to avoid the feared stimulus, often significantly restricting his or her activity in the process (see Case 6.5). A person with an elevator phobia, for example, will choose to walk up many flights of stairs rather than take the elevator. A specific phobia you might recognize include claustrophobia (fear of small spaces), arachnophobia (spiders), hydrophobia (water), and acrophobia (heights).

|

| Reprinted with permission from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, (Copyright ©2013). American Psychiatric Association. All Rights Reserved. |

CASE 6.5 • FROM THE OUTSIDE: A Specific Phobia (Hydrophobia)

Kevin described an experience in which he almost drowned when he was 11. He and his parents were swimming in the Gulf of Mexico, in a place where there were underwater canyons with currents that would often pull a swimmer out to sea. He remembered the experience very distinctly. He was standing in water up to his neck, trying to see where his parents were. Suddenly, a large wave hit him and dragged him into one of the underwater canyons. Fortunately, someone on shore saw what had happened and rescued him. After the experience, he became very much afraid of the ocean, and the fear generalized to lakes, rivers, and large swimming pools. He avoided them all.

(McMullin, 1986, p. 165)

DSM-5 lists five types or categories of specific phobia: animal, natural environment, blood-injection-injury, situational, and “other” (American Psychiatric Association, 2013):

- The animal type of specific phobia pertains to an extreme fear or avoidance of a kind of animal; commonly feared animals include snakes and spiders. Symptoms of the animal type of specific phobia usually emerge in childhood. People with a phobia for one kind of animal often also have a phobia for another kind of animal.

- The natural environment type of specific phobia typically focuses on heights, water, or storms. Phobias about the natural environment typically emerge during childhood.

- The blood-injection-injury type of specific phobia produces a strong response to seeing blood, having injections, sustaining bodily injuries, or watching surgery. This type of phobia runs in families and emerges in early childhood. A unique response of this specific phobia involves first an increased arousal, then a rapid decrease in heart rate and blood pressure, which often causes fainting. Among people with this type of phobia, over half report having fainted in response to a feared stimulus (Öst, 1992).

- A situational type of specific phobia involves a fear of a particular situation, such as being in an airplane, elevator, or other enclosed space, or of driving a car. Some people develop this type of phobia in childhood, but in general it has a later onset, often in the mid-20s. People with this type of phobia tend to experience more panic attacks than do people with other types of specific phobia (Lipsitz et al., 2002). Situational phobia has a gender ratio, age of onset, and family history similar to those of panic disorder or agoraphobia.

- Other type of specific phobia includes any such phobia that does not fall into the other four categories. Examples of specific phobias that would be classified as “other” are a fear of costumed characters (such as clowns at a circus) and a phobic avoidance of situations that may lead to choking or vomiting.

Specifics About Specific Phobia

As noted in TABLE 6.12, the majority of people who have one sort of specific phobia are likely to have at least one more. This high comorbidity among types of specific phobia has led some researchers to suggest that, like social anxiety disorder, specific phobia may take two forms: a focused type that is limited to a specific stimulus and a more generalized type that involves fear of various stimuli (Stinson et al., 2007).

| Prevalence |

|

| Comorbidity |

|

| Onset |

|

| Course |

|

| Gender Differences |

|

| Cultural Differences |

|

| Source: Unless otherwise noted, information in the table is from American Psychiatric Association, 2013. |

The unrealistic fears and extreme anxiety of a specific phobia occur in the presence of the feared stimulus but may even occur when simply thinking about it. Often, people with a specific phobia fear that something bad will happen as a result of contact with the stimulus: “What if I get stuck in the tunnel, and it cracks open and floods?” “What if the spider bites me, and I get a deadly disease?” People may also be afraid of the consequences of their reaction to the phobic stimulus, such as losing control of themselves or not being able to get help: “What if I faint or have a heart attack while I’m in the tunnel?” or, “What if I mess my pants after the spider bites me?” In this sense, the fear of somehow losing control is similar to that in panic disorder (Horwath et al., 1993).

There is a very long list of stimuli to which people have developed phobias (see www.phobialist.com), but people do not seem to develop specific phobias toward all kinds of stimuli; for example, a phobia of flowers is extremely unusual. Humans, like other animals, have a natural readiness for certain stimuli to produce certain conditioned responses. This preparedness means that less learning from experience is needed to produce the conditioning (Öhman et al., 1976). Some psychologists (Menzies & Parker, 2001; Öhman, 1986) propose that such preparedness has an evolutionary advantage: People are more readily afraid of objects or situations that could lead to death, such as being too close to the edge of a cliff (and falling off) or being bitten by a poisonous snake or spider. According to this view, those among our early ancestors who were afraid of these stimuli and avoided them were more likely to survive and reproduce—and thus passed on genes that led their descendants to be prepared to fear these stimuli.

184

Understanding Specific Phobia

As we see in the following sections, neurological and psychological factors appear to contribute to specific phobia more heavily than do social factors.

Neurological Factors

Researchers are making good headway in understanding the neurological factors that underlie specific phobia.

Brain Systems and Neural Communication

Perhaps not surprisingly, our old friend the amygdala is again implicated in an anxiety disorder. In fact, the amygdala appears to have a hair-trigger in patients with specific phobia. For example, in one fMRI study, patients who were phobic of spiders and control participants were asked to match geometric figures. In this study, the trick was that in the background behind each figure—which was completely irrelevant to the task of matching the figures—was a picture of either a spider or a mushroom (because no one in the study was afraid of mushrooms). Even in this task, where the participants were not paying attention to the background pictures, the amygdala of the patients with the phobia was more strongly activated in response to the spiders than the mushrooms; this was not true for the control participants (Straube et al., 2006).

In addition, the sort of anxiety evoked by specific phobia is associated with too little of the inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA (File et al., 1999). When a benzodiazepine (such as diazepam, or Valium) binds to the appropriate receptors, it facilitates the functioning of GABA—and the drug thereby ultimately produces a calming effect.

Genetics

Researchers have discovered that some genes predispose people to develop a particular specific phobia, whereas other genes predispose people to develop some sort of specific phobia but do not affect which particular type it will be (Kendler et al., 2001; Lichtenstein & Annas, 2000). According to one theory, genetic differences may cause parts of the brain related to fear (in particular, the amygdala) to be too reactive to specific stimuli; that is, the amygdala is “prepared” to overreact to a specific stimulus, which leads to a specific phobia of that stimulus. In addition, some people’s brains may generally be more prepared in this way than others’, and so they are more likely to develop a specific phobia although not any particular one (LeDoux, 1996).

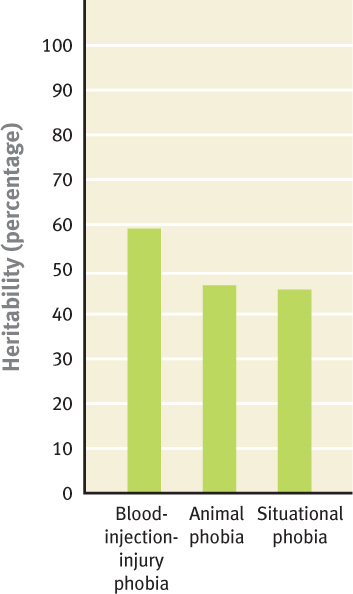

Furthermore, genes do not have equal effects for all types of specific phobia: The different types of specific phobia appear to be influenced to different degrees by genetics and the environment (see Figure 6.5 for the heritabilities of types of specific phobia). However, genetics cannot be all there is to it: If it were, then when one identical twin has specific phobia, so would the other twin, but this is not always the case. As we’ve noted before, the genes predispose, but rarely determine. Rather, certain environmental events are necessary to trigger the disorder. For example, family environment has proven to be an important risk factor for specific phobia (Kendler et al., 2001).

The sum of the research findings about neurological factors suggests that particular life experiences can lead to a particular specific phobia for people who—through genes or other life experiences—are neurologically vulnerable (Antony & Barlow, 2002).

185

Psychological Factors

Life experiences always have their impact via how a person perceives and interprets them. Thus, psychological factors play a key role in whether a person will develop a specific phobia. Three primary psychological factors contribute to a specific phobia: a tendency to overestimate the probability of a negative event’s occurring based on contact with the feared stimuli, classical conditioning, and operant conditioning.

Faulty Estimations

Similarly to what we saw with social anxiety disorder, people who have a specific phobia have a particular cognitive bias—they believe strongly that something bad will happen when they encounter the feared stimulus (Tomarken et al., 1989). They also overestimate the probability that an unpleasant event, such as falling from a high place or an airplane’s crashing into a tall building, will occur (Pauli et al., 1998). People who have a specific phobia may also have perceptual distortions related to their feared stimulus. For example, a person with a spider phobia may perceive that a spider is moving straight toward him or her when it isn’t (Riskind et al., 1995).

Conditioning: Classical and Operant

From a learning perspective, classical conditioning and operant conditioning could account for the development and maintenance of a specific phobia. Watson and Rayner’s conditioning of Little Albert’s fear of rats was the first experimental induction of a classically conditioned phobia (see Chapter 2). However, some recent research has questioned the importance of classical conditioning in the development of specific phobia. In studies of people with a phobia of water, heights, or spiders, researchers usually have not found evidence that classical conditioning played the role that had been predicted (Menzies & Clarke, 1993a, 1993b, 1995a, 1995b; Poulton et al., 1999). Further evidence for a limited role of classical conditioning comes from everyday observations: Many people experience the pairing of conditioned and unconditioned stimuli but do not become phobic.

Regardless of the extent of the role of classical conditioning, operant conditioning clearly plays a key role in maintaining a specific phobia: By avoiding the feared stimulus, a person can decrease the fear and anxiety that he or she would experience in the presence of it, which reinforces the avoidance.

Social Factors: Modeling and Culture

Sometimes, simply seeing other people being afraid of a particular stimulus is enough to make the observer become afraid of that stimulus (Mineka et al., 1984). For example, if as a young child, you saw your older cousin become agitated and anxious when a dog approached, you might well learn to do the same. Similarly, repeated warnings about the dangers of a stimulus can increase the risk of developing a specific phobia of that stimulus (Antony & Barlow, 2002).

Modeling is not the only way that culture can exert an effect on the content of specific phobia. Consider the fact that people in India are twice as likely as people in England to have a phobia of animals, darkness, or bad weather but are only half as likely to have social anxiety disorder or agoraphobia (Chambers et al., 1986). One explanation for this finding is that people in India are apt to spend more time at home than their English counterparts, so they have less opportunity to encounter feared social situations. Similarly, dangerous and predatory animals are more likely to roam free in India than in England.

186

Feedback Loops in Understanding Specific Phobia

ONLINE

A person may be neurologically vulnerable to developing a specific phobia in part because of his or her genes, which may make his or her amygdala “prepared” to react too strongly to certain stimuli. Through observing others’ fear of a specific stimulus (social factor), the person can become afraid and develop faulty cognitions, which can lead to distorted thinking and the conditioning of false alarms to the feared stimulus (psychological factors). And, once the person begins to avoid the stimulus, the avoidance behavior is negatively reinforced. This behavior in turn affects not only the person’s beliefs but also his or her social interactions (social factors).

Treating Specific Phobia

Treatment for specific phobia generally targets one type of factor, although the beneficial changes affect all the factors.

Targeting Neurological Factors: Medication

Medication, such as a benzodiazepine, may be prescribed for a specific phobia (alone or in combination with CBT), but this is generally not recommended. Medication is usually unnecessary because CBT treatment—even a single session—is highly effective in treating a specific phobia (Ellison & McCarter, 2002).

Targeting Psychological Factors

If you had to choose an anxiety disorder to have, specific phobia probably should be your choice. This is the anxiety disorder most treatable by CBT, with up to 90% lasting improvement rates even after only one session (Gitin et al., 1996; Öst, Salkovskis, & Hellström, 1991).

Behavioral Method: Exposure

The behavioral method of graded exposure has proven effective in treating specific phobia (Vansteenwegen et al., 2007), and is considered a first-line treatment. With this method, the patient and therapist progress through an individualized hierarchy of anxiety-producing stimuli or events as fast as the patient can tolerate; this process is like that used in exposure treatment for social anxiety discussed earlier in the chapter, but in this case substituting the specific feared stimulus for the feared social situation or interaction. Moreover, recent research on treating phobias with exposure suggests that virtual reality exposure works as well as in vivo exposure, at least for certain phobias (Pull, 2005), such as of flying and heights (Coelho et al., 2009; Emmelkamp et al., 2001, 2002), and this technique is part of many treatment programs for fear of flying.

Cognitive Methods

Cognitive methods for treating a specific phobia are similar to those used to treat other anxiety disorders, such as panic disorder, agoraphobia, and social anxiety disorder. The therapist and patient identify illogical thoughts pertaining to the feared stimulus, and the therapist helps highlight discrepant information and challenges the patient to see the irrationality of his or her thoughts and expectations. TABLE 6.13 provides an example of thoughts that someone with claustrophobia—a fear of enclosed spaces—might have.

|

| Source: Antony, Craske, & Barlow, 1995, p. 105. For more information see the Permissions section. |

In addition, group CBT may be appropriate for some kinds of phobias, such as fear of flying or of spiders (Rothbaum et al., 2006; Van Gerwen et al., 2006). However, unlike group CBT for social anxiety disorder, group treatment for specific phobia does not directly target social factors; rather, group CBT is a cost-effective way to teach patients behavioral and cognitive methods to overcome their fears.

187

Targeting Social Factors: A Limited Role for Observational Learning

Observational learning may play a role in the development of a specific phobia, but to many researchers’ surprise, seeing others model how to interact normally with the feared stimulus generally is not an effective treatment for specific phobia. Perhaps observational learning is not effective because patients’ cognitive distortions are powerful enough to negate any positive effects modeling might provide. For instance, someone with a spider phobia who observes someone else handling a spider might think, “Well, that person isn’t harmed by the spider, but there’s no guarantee that I’ll be so lucky!”

Feedback Loops in Treating Specific Phobia

ONLINE

When treatment is effective in creating lasting change in one type of factor, it causes changes in the other factors. Consider dental phobia and its treatment. Over 16% of people between the ages of 18 and 26 have significant dental anxiety, according to one survey (Locker et al., 2001). One study examined the effect of a single session of CBT on dental phobia (Thom et al., 2000). The treatment group was given stress management training and imaginal exposure to dental surgery 1 week prior to the surgery; these patients were asked to review the stress management techniques and visualize dental surgery daily during the intervening week. Another group of people with dental phobia was only given a benzodiazepine 30 minutes before surgery. A third group was given nothing; this was the control group. Both types of treatment led to less anxiety during the dental surgery than was reported by the control group. However, those in the CBT group continued to maintain and show further improvement at a 2-month follow-up: 70% of them went on to have subsequent dental work, whereas only 20% of those in the benzodiazepine group and 10% of the control group did so.

The neuropsychosocial approach leads us to consider how the factors and their feedback loops interact to treat such a specific phobia: The medication, although temporarily decreasing anxiety (neurological factor), did not lead to sustained change either in brain functioning or in thoughts about dental procedures. The CBT, in contrast, targeted psychological factors and also led to changes in a neurological factor—brain functioning associated with decreased anxiety and arousal related to dental surgery. In turn, these changes led to social changes—additional dental work. And the added dental visits presumably led to better health, which in turn affected the participants’ view of themselves and their interactions with others. Indeed, if the visits had cosmetic effects (such as a nicer smile), their social benefits would be even more evident. Such feedback loops underlie the treatment of all types of specific phobia.

188

Thinking Like A Clinician

Iqbal is horribly afraid of tarantulas, refusing to enter insect houses at zoos. Do you need any more information before determining whether Iqbal has a specific phobia of tarantulas? If so, what would you need to know? If not, do you think he has a specific phobia? Explain. How might Iqbal have developed his fear of tarantulas? What factors are likely to have been involved in its emergence and maintenance? Suppose Iqbal decides that he wants to “get rid of” his fear of tarantulas. What treatments are likely to be effective, and what are the advantages and disadvantages of each?