7.1 Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder and Related Disorders

After his parents’ deaths, Hughes’s health concerns increased, and his profound fear of germs—and the rituals and behaviors that he used to limit what he believed were possible routes of contamination—came to restrict his life severely. But the protective rituals and behaviors extended beyond himself (and beyond rational thinking); he made his aides and associates undertake similar extreme precautions even though that did not, in fact, decrease his risk:

He viewed anyone who came near as a potential germ carrier. Those whose movements he could control—his aides, drivers, and message clerks—were required to wash their hands and slip on thin white cotton gloves…before handing him documents or other objects. Aides who bought newspapers or magazines were instructed to buy three copies—Hughes took the one in the middle. To escape dust, he ordered unused windows and doors of houses and cars sealed with masking tape.

(Barlett & Steele, 1979, p. 175)

And it wasn’t only exposure to germs that Hughes tried to control. Throughout his life, he’d been overly preoccupied with details; at one time or another, he concerned himself with every aspect of his companies—even demanding that employees conduct a detailed study of the vending machines at the Hughes Aircraft Company. Hughes’s preoccupations and ritualistic behaviors were symptoms of obsessive-compulsive disorder.

What Is Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder?

Obsessions Intrusive and unwanted thoughts, urges, or images that persist or recur and usually cause distress or anxiety.

Howard Hughes had obsessions and compulsions. Obsessions are intrusive and unwanted thoughts, urges, or images that persist or recur and usually cause distress or anxiety; people try to ignore, suppress, or neutralize these thoughts, urges, or images (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). For instance, Hughes had obsessions about germs; his preoccupations about them were intrusive and persistent. Worries about actual problems (such as, “How can I pay my bills this month?” or, “I don’t think I can finish this project by the deadline”) are not considered obsessions.

Compulsions Repetitive behaviors or mental acts that a person feels driven to carry out and that usually must be performed according to rigid “rules” or correspond thematically to an obsession.

Whereas obsessions involve thoughts, urges, and images, compulsions involve behaviors. A compulsion is an excessive repetitive behavior (such as avoiding stepping on sidewalk cracks) or mental act (such as silently counting to 10) that a person feels driven to carry out; a compulsion usually must be performed according to rigid “rules” or corresponds thematically to an obsession and serves to “neutralize” the obsession and decrease anxiety or distress. For instance, Howard Hughes was obsessed by the possibility that he might be exposed to germs and was compelled to behave in ways that he believed would protect him from such germs.

Obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) A disorder characterized by one or more obsessions or compulsions.

The key element of obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) is characterized by having one or more obsessions or compulsions (See TABLE 7.1; American Psychiatric Association, 2013). The obsession can cause great distress and anxiety, despite a person’s attempts to ignore or drive out the intrusive thoughts. Most people with OCD recognize that the beliefs that underlie their obsessions and compulsions are not valid in all situations. In a minority of cases, though, people may believe that their OCD-related beliefs are rational, and in DSM-5 such people might be considered to have reduced insight into their condition (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

|

| Reprinted with permission from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, (Copyright ©2013). American Psychiatric Association. All Rights Reserved. |

197

TABLE 7.2 identifies common types of obsessions and compulsions. Obsessions (listed on the left side of TABLE 7.2) include preoccupations with contamination, order, fear of losing control, and doubts about whether the patient performed an action. As noted earlier, compulsive behaviors are usually related to an obsession or anxiety associated with a particular situation or stimulus (also listed in TABLE 7.2) and include washing, ordering, counting, and checking (Mataix-Cols et al., 2005). Performing the behavior prevents or relieves the anxiety, but only temporarily. However, compulsions that relieve anxiety can take significant amounts of time to complete—sometimes more than an hour—and often create distress or impair functioning. Hughes clearly had compulsive symptoms of the contamination-washing type and had ordering types of obsessions and compulsions.

| Type of obsession | Examples of obsessions: People with OCD may be preoccupied with anxiety-inducing thoughts about… | Type of compulsion | Examples of compulsions: In order to decrease anxiety associated with an obsession, people may repeatedly be driven to… |

| Contamination | germs, dirt | Washing | wash themselves or objects in order to minimize any imagined contamination |

| Order | objects being disorganized, or a consuming desire to have objects or situations conform to a particular order or alignment | Ordering | order objects, such as canned goods in the cupboard, so that everything in the environment is “just so” (and often making family members and friends maintain this order) |

| Losing control | the possibility of behaving impulsively or aggressively, such as yelling during a funeral | Counting | count in response to an unwanted thought, which leads to a sense that the unwanted thought is neutralized (for instance, after each thought of blurting out an obscenity, methodically counting to 50) |

| Doubt | whether an action, such as turning off the stove, was performed | Checking | check that they did, in fact, perform a behavior about which they had doubts (such as repeatedly checking that the stove is turned off) |

Like the other anxiety disorders we’ve discussed, OCD often involves an unrealistic or disproportionate fear—in this case, of adverse consequences if the compulsive behavior is not completed. For instance, people with an obsession about contamination, like Hughes, fear that if all germs aren’t washed off, they will die of some disease. Additional facts about OCD are provided in TABLE 7.3, and Case 7.1 describes one woman’s experience with OCD.

| Prevalence |

|

| Comorbidity |

|

| Onset |

|

| Course |

|

| Gender Differences |

|

| Cultural Differences |

|

| Source: Unless otherwise noted, information in the table is from American Psychiatric Association, 2000, 2013. |

CASE 7.1 • FROM THE INSIDE: Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

For someone with OCD, just getting up in the morning and getting dressed can be fraught with trials and tribulations:

Should I get up? It’s 6:15. No, I better wait till 6:16, it’s an even number. OK, 6:16, now I better get up, before it turns to 6:17, then I’d have to wait till 6:22.

OK, I’ll get up, OK, I’m up, WAIT! I better do that again. One foot back in bed, one foot on the floor, now the other foot in bed and the opposite on the floor. OK. Let’s take a shower, WAIT! That shoe on the floor is pointing in the wrong direction, better fix it. Oops, there’s a piece of lint there, I better not set the shoe on top of it…. OH, JUST TOUCH THE SHOE TWICE AND GET OUTTA HERE!

All right, I got to the bedroom door without touching anything else, but I better step through and out again, just to be sure nothing bad will happen. THERE, THAT WAS EASY! Now to the bathroom. I better turn that light on, NO, off, NO, on, NO, off, NO, on, KNOCK IT OFF! All right, I’m done using the toilet, better flush it. OK, now spin around, wait for the toilet to finish a flush, now touch the handle, now touch the seat, remember you have to look at every screw on the toilet seat before you turn around again. OK, now turn around and touch the seat again, look at all the screws again. OK, now close the cover.

OK, let’s get some underwear. I want to wear the green ones because they fit the best, but they’re lying on top of the T-shirt my grandmother gave me, and her husband (my grandfather) died last year, so I better wash those again before I wear them. If I wear them, something bad might happen.

(Steketee & White, 1990, pp. 4–5)

Hoarding disorder An obsessive-compulsive-related disorder characterized by persistent difficulty throwing away or otherwise parting with possessions—to the point that the possessions impair daily life, regardless of the value of those possessions.

198

OCD clearly involves fears and anxieties; it also often involves compulsive behaviors over which patients feel they have no control. A number of other disorders, such as hair-pulling disorder (also referred to as trichotillomania), skin-picking disorder (also referred to as excoriation disorder), hoarding disorder, and body dysmorphic disorder share some of these features and are considered to be related to obsessive-compulsive disorder:

Steve Russell/Toronto Star via Getty Images

199

- Hair-pulling disorder is characterized by the persistent compulsion to pull one’s hair, leading to hair loss and distress or impaired functioning.

- Skin-picking disorder is characterized by compulsive skin picking to the point that lesions emerge on the skin.

- Hoarding disorder is characterized by persistent difficulty throwing away or otherwise parting with possessions—to the point that the possessions impair daily life, regardless of the value of those possessions.

- Body dysmorphic disorder, discussed in detail below, is characterized by preoccupations with a perceived defect in appearance and repetitive behaviors to hide the perceived defect.

What these four disorders have in common with OCD is either or both of the following: preoccupations that arise from beliefs that are out of proportion to actual danger and/or compulsive behaviors that reduce tension or anxiety.

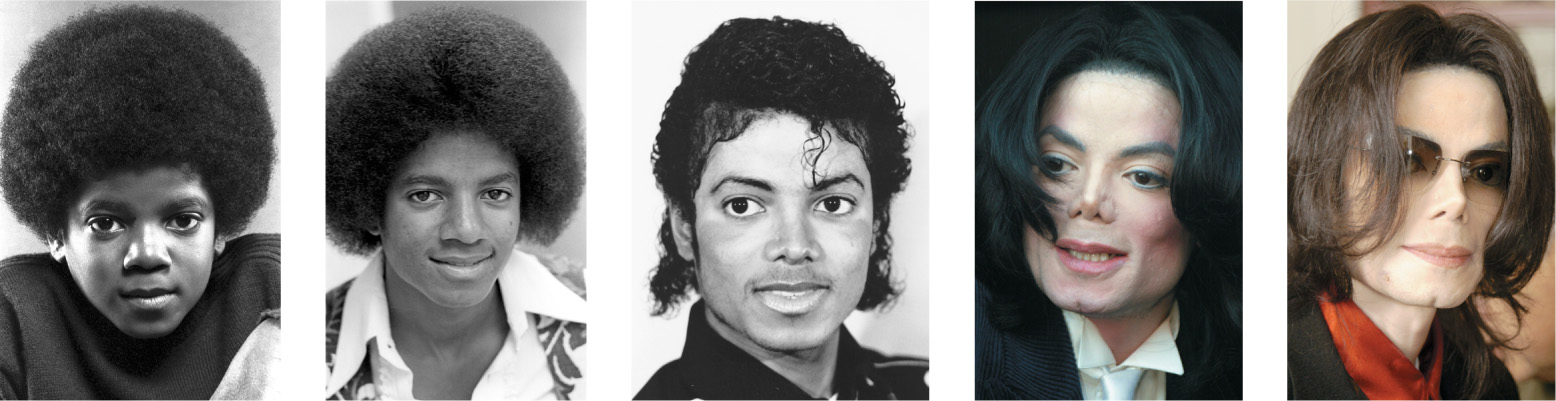

What Is Body Dysmorphic Disorder?

Body dysmorphic disorder A disorder characterized by excessive preoccupation with a perceived defect or defects in appearance and repetitive behaviors to hide the perceived defect.

It’s a common experience to believe that a pimple on your forehead appears like a red beacon for others to see; many people will try to cover up or hide a pimple. It’s also common for people with a receding hairline to change their hairstyle to make the hair loss less noticeable. What isn’t common—and, in fact, signals a psychological disorder—is when a slight imperfection in appearance, even an imagined defect, causes significant distress (Lambrou et al., 2011) or takes up so much time and energy that daily functioning is impaired. These are the signs of body dysmorphic disorder. The specific DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for this disorder (TABLE 7.4) indicate why body dysmorphic disorder is considered to fall on the spectrum of OCD-related disorders: It involves preoccupations (some might say obsessions) about a perceived defect and, at some point, repetitive mental acts or behaviors (that might be compulsive) related to these preoccupations. The person might repeatedly compare his or her appearance to other people’s (mental act) or repeatedly groom himself or herself or seek reassurance from others about appearance (behavior). As with OCD, the behaviors can consume hours.

|

| Reprinted with permission from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, (Copyright ©2013). American Psychiatric Association. All Rights Reserved. |

GETTING THE PICTURE

©Katja Heinemann/Aurora Photoa/Corbis

200

Common preoccupations for people with body dysmorphic disorder are thinning or excessive hair, acne, wrinkles, scars, complexion (too pale, too dark, too red, and so on), facial asymmetry, or the shape or size of some part of the face or body. Some people are preoccupied with the belief that they aren’t muscular enough or that their body build is too slight. The “defect” (or “defects”) may change over the course of the illness (K. A. Phillips, 2001). People with body dysmorphic disorder may think that others are staring at them or talking about a “defect.” Up to half of those with body dysmorphic disorder are delusional—that is, they believe their perception of a “defect” is accurate and not exaggerated (Phillips et al., 1994). Although Howard Hughes had beliefs about his body (related to germs), they do not appear to have been beliefs about bodily defects.

People with body dysmorphic disorder may compulsively exercise, diet, shop for beauty aids, pick at their skin, try to hide perceived defects, or spend hours looking in the mirror (like Ms. A., described in Case 7.2, who believed that she had multiple defects). A person with body dysmorphic disorder may seek reassurance (“How do I look?”), but any positive effects of reassurance are transient; a half-hour later, the person with body dysmorphic disorder may ask the same question—even of the same person! These behaviors, which are intended to decrease anxiety about appearance, actually end up increasing anxiety.

CASE 7.2 • FROM THE OUTSIDE: Body Dysmorphic Disorder

Ms. A was an attractive 27-year-old single white female who presented with a chief complaint of “I look deformed.” She had been convinced since she was a child that she was ugly, and her mother reported that she had “constantly been in the mirror” since she was a toddler. Ms. A was obsessed with many aspects of her appearance, including her “crooked” ears, “ugly” eyes, “broken out” skin, “huge” nose, and “bushy” facial hair. She estimated that she thought about her appearance for 16 hours a day and checked mirrors for 5 hours a day. She compulsively compared herself with other people, repeatedly sought reassurance about her appearance…, applied and reapplied makeup for hours a day, excessively washed her face, covered her face with her hand, and tweezed and cut her facial hair. As a result of her appearance concerns, she had dropped out of high school…. She avoided friends and most social interactions. Ms. A felt chronically suicidal and had attempted suicide twice because, as she stated, “I’m too ugly to go on living.”

(K. A. Phillips, 2001, pp. 75–76)

Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

Chris Walter/Wire Image/Getty Images

Frazer Harrison/Getty Images

Michael A. Mariant-Pool/Getty Images

201

People who have body dysmorphic disorder may feel so self-conscious about a perceived defect that they avoid social situations (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), which results in their having few (or no) friends and no romantic partner. Some try to eliminate a “defect” through medical or surgical treatment such as plastic surgery, dental work, or dermatological treatment. But surgery often does not help; in fact, the symptoms of the disorder can actually be worse after surgery (Veale et al., 2003). In extreme cases, when some people with body dysmorphic disorder can’t find a doctor to perform the treatment they think they need, they may try to do it themselves (so-called DIY, or do-it-yourself, surgery). TABLE 7.5 presents additional facts about body dysmorphic disorder.

| Prevalence |

|

| Comorbidity |

|

| Onset |

|

| Course |

|

| Gender Differences |

|

| Cultural Differences |

|

202

Patients with body dysmorphic disorder exhibit a variety of cognitive biases. Such patients tend to focus their attention on isolated body parts and are hypervigilant for any possible bodily imperfections (Grocholewski et al., 2012). They also engage in catastrophic thinking, believing that bodily imperfections will lead to dire consequences; for example, the person might believe that having a pimple will lead others to think he or she is deformed (Buhlmann et al., 2008; Lambrou et al., 2012).

In addition, people with body dysmorphic disorder often engage in behaviors that temporarily reduce their anxiety. For example, they might try to avoid mirrors (and possibly people) or develop new ways to hide a “defect”—with painstakingly applied makeup or contrived use of clothing or hats (K. A. Phillips, 2001). If you think that some of the descriptions of the symptoms of body dysmorphic disorder resemble those of anxiety-related disorders, not just OCD, you’re right. Like phobia disorders (agoraphobia, social anxiety disorder, and specific phobias), body dysmorphic disorder can lead the person to avoid anxiety-causing stimuli. Like social anxiety disorder, it involves an excessive fear of being evaluated negatively. And like OCD, it involves persistent preoccupations and compulsive behaviors. Because body dysmorphic disorder is related to OCD, in order to understand the former, we look to research on the latter.

Understanding Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

Howard Hughes had neurological and psychological vulnerabilities for OCD that may have been exacerbated by psychological and social factors. However, with OCD, social factors have less influence than do neurological and psychological factors.

Neurological Factors

Researchers have made much progress in understanding the neurological underpinnings of OCD.

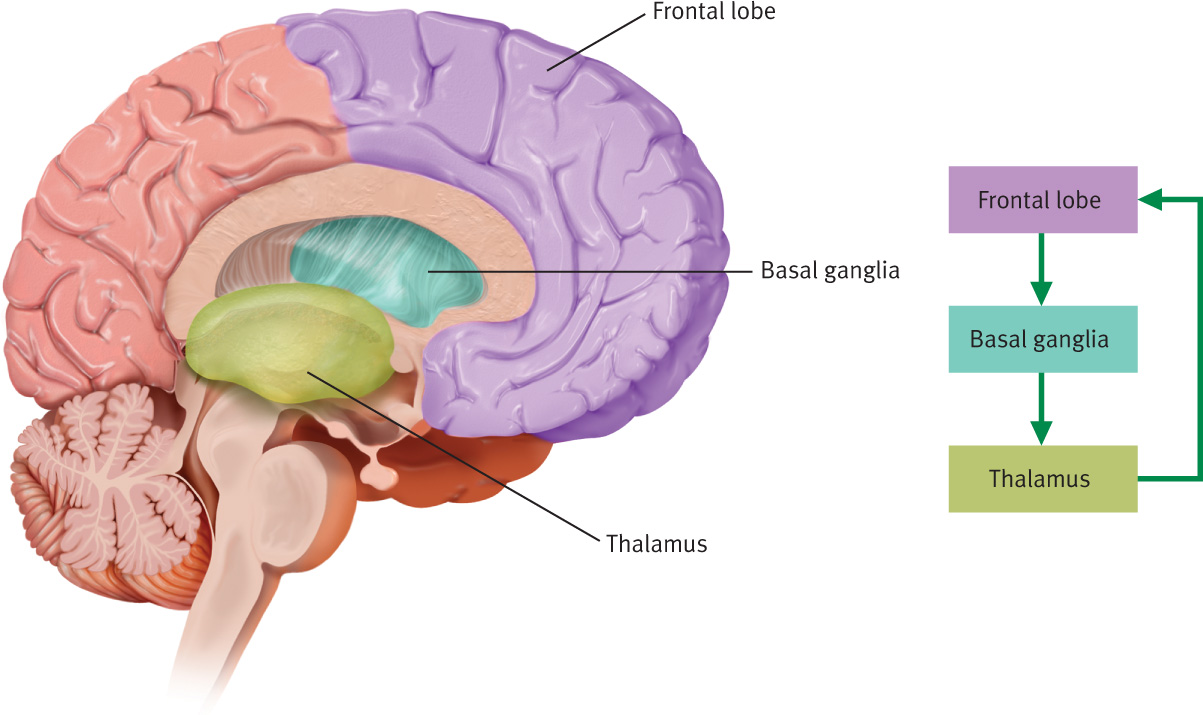

Brain Systems and Neural Communication

In general, when the frontal lobes trigger an action, there is feedback from the basal ganglia, in part via the thalamus (a brain structure involved in attention). Sometimes this feedback sets up a loop of repetitive activity, as shown in Figure 7.1 (Breiter et al., 1996; Rapoport, 1991; Rauch et al., 1994, 2001). Many researchers now believe that this neural loop plays a key role in obsessive thoughts, which intrude and cannot be stopped easily. Performing a compulsion might temporarily stop the obsessive thoughts by reducing the repetitive neural activity (Insel, 1992; Jenike, 1984; Modell et al., 1989). (But soon after the compulsive behavior stops, the obsessions typically resume.)

203

Much research has focused on whether OCD arises from abnormalities in the basal ganglia and frontal lobes in particular (Pigott et al., 1996; Saxena & Rauch, 2000). In fact, neuroimaging studies have revealed that both a part of the frontal cortex and the basal ganglia function abnormally in OCD patients (Baxter, 1992; Berthier et al., 2001; Saxena et al., 1998). This abnormal functioning could well prevent the frontal lobe from cutting off the loop of repetitive neural activity, as it appears to do in people who do not have this disorder.

OCD appears to arise in large part because brain circuits don’t operate normally, but why don’t they do so? One reason may be that people with OCD have too little of the neurotransmitter serotonin, which allows unusual brain activity to occur (Mundo, Richter, et al., 2000). And, in fact, medications that increase the effects of serotonin (such as Prozac), often by preventing reuptake of this neurotransmitter at the synapse (see Chapter 5), can help to treat OCD symptoms (Micallef & Blin, 2001; Thomsen, et al., 2001).

Genetics

Twin studies have shown that if one monozygotic (identical) twin has OCD, the other is very likely (65%) to have it. As expected if this high rate reflects common genes, the rate is lower (only 15%) for dizygotic twins (Pauls et al., 1991). Moreover, as you would expect from the results of the twin studies, OCD is more common among relatives of OCD patients (10% of whom also have OCD) than among relatives of control participants (of whom only 2% also have OCD) (Pauls et al., 1995).

However, although such studies have documented a genetic contribution to OCD, the link is neither simple nor straightforward: Members of the family of a person with OCD are more likely than other people to have an anxiety disorder, not OCD specifically (Black et al., 1992; Smoller et al., 2000).

When many people first learn about OCD, they recognize tendencies they’ve noticed in themselves. If you’ve had this reaction while reading this section, you shouldn’t worry: OCD may reflect extreme functioning of brain systems that function the same way in each of us to produce milder forms of such thinking.

Psychological Factors

Psychological factors that help to explain OCD focus primarily on the way that operant conditioning affects compulsions and on the process by which normal obsessional thoughts become pathological.

Behavioral Explanations: Operant Conditioning and Compulsions

Compulsive behavior can provide short-term relief from anxiety that is produced by an obsession. Operant conditioning occurs when the behavior is negatively reinforced: Because the behavior (temporarily) relieves the anxiety, the behavior is more likely to recur when the thoughts arise again. All of Howard Hughes’s various eccentric behaviors—his washing, his precautions against germs, his hoarding of newspapers and magazines—temporarily relieved his anxiety.

204

Cognitive Explanations: Obsessional Thinking

If you’ve ever had a crush on someone or been in love, you may have spent a lot of time thinking about the person—it may have even felt like an obsession. Such obsessions are surprisingly frequent (Weissman et al., 1994), but they don’t usually develop into a disorder. One theory about how a normal obsession becomes part of OCD is that the person decides that his or her thoughts refer to something unacceptable, such as killing someone or, as was the case with Howard Hughes, catching someone else’s illness (Salkovskis, 1985). These obsessive thoughts, which the person believes imply some kind of danger, lead to very uncomfortable feelings. Mental or behavioral rituals arise in order to reduce these feelings.

Consistent with this view, researchers have found that some mental processes function differently in people with OCD than in people without the disorder. In particular, such patients are more likely to pay attention to and remember threat-relevant stimuli, and they have impaired processing of complex visual stimuli (as, for example, is necessary to decide whether an object has been touched by a dirty or clean tissue among people with contamination fears; Muller & Roberts, 2005; Radomsky et al., 2001). Such processing may make threatening stimuli easier to remember and harder to ignore, which keeps them in the patients’ awareness longer than normal (Muller & Roberts, 2005) and makes the irrational fears seem more plausible (Giele et al., 2011).

Social Factors

Two types of social factors can contribute to OCD: stress and culture.

Stress

The onset of OCD often follows a stressor, and the severity of the symptoms is often proportional to the severity of the stressor (Turner & Beidel, 1988). However, such findings are not always easy to interpret. For example, one study found that people with more severe OCD tend to have more kinds of family stress and are more likely to be rejected by their families (Calvocoressi et al., 1995). Note, however, that the direction of causation is not clear: Although stress in the family may cause the greater severity of symptoms, it is also possible that the more severe symptoms led the families to reject the patients.

Stress greatly affected the course of Hughes’s symptoms. For much of his 20s, 30s, and early 40s, he was able to function relatively well, given the freedom his wealth and position provided. However, during one particularly stressful period in his late 30s, “Hughes began repeating himself at work and in casual conversations. In a series of memoranda on the importance of letter writing, he dictated, over and over again, ‘a good letter should be immediately understandable…a good letter should be immediately understandable…a good letter should be immediately understandable…” (Barlett & Steele, 1979, p. 132).

By the time Hughes was in his 50s, the stressors increased, and his functioning diminished. There were periods when he was so preoccupied with his germ phobia that he couldn’t pay attention to anything else.

Culture

Different countries have about the same prevalence rates of OCD, although culture and religion can help determine the particular content of some obsessions or compulsions (Weissman et al., 1994). For instance, religious obsessions and praying compulsions are more common among Turkish men than French men (Millet et al., 2000) and more common among Brazilians than Americans or Europeans (Fontenelle et al., 2004). And a devoutly religious patient’s symptoms can relate to the specific tenets and practices of his or her religion (Shooka et al., 1998): Someone who is Catholic may have obsessional worries about having impure thoughts or feel a compulsion to go to confession multiple times each day. In contrast, devout Jews or Muslims may have symptoms that focus on extreme adherence to religious dietary laws.

205

Feedback Loops in Understanding Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

ONLINE

One neurological factor that contributes to OCD appears to be a tendency toward increased activity in the neural loop that connects the frontal lobes and the basal ganglia (neurological factor). A person with such a neurological vulnerability might learn early in life to regard certain thoughts as dangerous because they can lead to obsessions. When these thoughts appear later in life at a time of stress, someone who is vulnerable may become distressed and anxious about the thoughts and try to suppress them. But a conscious attempt to suppress unwanted thoughts often has the opposite effect: The unwanted thoughts become more likely to persist (Salkovkis & Campbell, 1994; Wegner et al., 1987). Thus, the intrusive thoughts cause additional distress, and so the person tries harder to suppress them, creating a vicious cycle (psychological factor).

The content of a person’s unwanted thoughts determines the extent to which those thoughts are unacceptable. When a person wants to suppress the unwanted thoughts, he or she develops rituals and avoidance behaviors to increase a sense of control and decrease anxiety; these behaviors temporarily reduce anxiety and are thus reinforced. But the thoughts cannot be fully controlled and become obsessive; the obsessions and compulsions impair functioning and can affect relationships. The person with OCD may expect family members and friends to conform to compulsive guidelines; these people and others can become frustrated and dismayed at the patient’s rituals and obsessions—which in turn can produce more stress for the patient (social factors).

Treating Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

The primary targets of treatment for OCD are usually either neurological or psychological factors.

Targeting Neurological Factors: Medication

An SSRI is usually the type of medication used first to treat OCD: paroxetine (Paxil), sertraline (Zoloft), fluoxetine (Prozac), fluvoxamine (Luvox), or citalopram (Celexa) (Soomro et al., 2008). OCD can also be treated effectively with the TCA clomipramine (Anafranil), although a higher dose is required than that prescribed for depression or other anxiety disorders (Rosenbaum, Arana et al., 2005). People who develop OCD in childhood are less likely to respond well to clomipramine or to other antidepressants (Rosario-Campos et al., 2001).

Hughes’s use of codeine and Valium did not appear to diminish his obsessions and compulsions significantly; in fact, such medications are not routinely prescribed for OCD. In any case, medication alone is not as effective as medication combined with behavioral treatment, such as exposure with response prevention (discussed in the following section). As with other anxiety disorders, when the medication is discontinued, OCD symptoms usually return (Foa et al., 2005).

Targeting Psychological Factors

Treatment that targets psychological factors focuses on decreasing the compulsive behaviors and obsessional thoughts. Both behavioral and cognitive methods are effective (Cottraux et al., 2001; Prazeres et al., 2013), and treatment may combine both types of methods (Franklin et al., 2002).

206

Behavioral Methods: Exposure With Response Prevention

Exposure with response prevention A behavioral technique in which a patient is carefully prevented from engaging in his or her usual maladaptive response after being exposed to a stimulus that usually elicits the response.

Patients with OCD often undertake exposure with response prevention. For the exposure part, the patient is exposed to the feared stimulus (such as touching dirt) or the obsessive thought (such as the idea that the stove was left on) and, for the response prevention part, the patient is prevented from engaging in the usual compulsion or ritual. For instance, if someone were afraid of touching dirt, she would touch dirt but would not then wash her hands for a while. Through exposure with response prevention, patients learn that nothing bad happens if they don’t perform their compulsive behavior; the fear and arousal subside without resorting to the compulsion, and they experience mastery. They survive the anxiety and in doing so exert control over the compulsion. When patients successfully respond differently to a feared stimulus, this mastery over the compulsion gives them hope and motivates them to continue to perform the new behaviors. Exposure with response prevention is also a technique used to treat body dysmorphic disorder.

Cognitive Methods: Cognitive Restructuring

The goal of cognitive methods is to reduce the irrationality and frequency of the patient’s intrusive thoughts and obsessions (Clark, 2005). Cognitive restructuring focuses on assessing the accuracy of these thoughts, making predictions based on them (“If I don’t go back to check the locks, I will be robbed”), and testing whether these predictions come to pass.

Although CBT for OCD hadn’t been sufficiently developed during Hughes’s lifetime, consider how it might have been used: There were periods when Hughes daily and “painstakingly used Kleenex to wipe ‘dust and germs’ from his chair, ottoman, side table, and telephone [for hours].” (Barlett & Steele, 1979, p. 233). During the same period of time, he didn’t have his sheets changed for months at a time; to make the sheets last longer, he laid paper towels over them and slept on those. Moreover, he bathed only a few times a year. Clearly, such behavior was at odds with rational attempts to protect against germs. CBT would have, in part, focused on his overestimation of the probability of contracting an illness and the irrationality of his precautions.

Targeting Social Factors: Family Therapy

Although psychological and neurological factors are the primary targets of treatment for OCD, in some cases, social factors may also be addressed—for example, through family therapy or consultation with family members. This aspect of treatment educates family members about the patient’s treatment and its goals and helps the family function in a more normal way. Family members and friends may have spent years conforming their behavior to the patient’s illness (e.g., using clean tissues when handing an object to the patient), and they may be afraid to change their own behavior as the patient gets better, for fear of causing a relapse.

Feedback Loops in Treating Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder

ONLINE

As we’ve seen, medication can be effective in treating the symptoms of OCD (at least as long as the patient continues to take it). Medication works by changing neurochemistry, which in turn affects thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. We’ve also seen that CBT is effective. How does CBT have its effects? Could it be that therapy changes brain functioning in the same way that medication does? Researchers set out to answer this question.

In one study, researchers used PET scans to assess brain functioning in two groups of OCD patients. One group received behavior therapy, and the other group received the SSRI fluoxetine (Prozac) to reduce OCD symptoms. Both behavior therapy and Prozac decreased activity in a part of the basal ganglia that is involved in automatic behaviors. Prozac also affected activity in two parts of the brain involved in attention: the thalamus and the anterior cingulate (Baxter et al., 1992). Later research replicated the effects of behavior therapy on the brain (Schwartz et al., 1996). Although the altered brain areas overlapped, CBT changed fewer brain areas than did medication—which may reflect the fact that medication may have side effects, whereas CBT does not.

207

In short, behavior therapy or CBT changes the brain (neurological factor). As the patient improves, personal relationships change (social factor): The time and energy that once went into the compulsions can be diverted to other areas of life, including relationships. Moreover, the patient experiences mastery over the symptoms and develops hope and a new view of himself or herself (psychological factors). In turn, this makes the patient more willing to continue therapy, which further changes the brain, and so on, in a happy cycle of mutual feedback loops among neurological, psychological, and social factors.

Thinking Like A Clinician

You visit a new friend. When you use her bathroom, you notice that all her toiletries seem very organized. Her kitchen is also neatly ordered. The next day, you notice that her classwork is unusually well organized—arranged neatly in color-coded folders and notebooks. You don’t think twice about it until she drops her open backpack and all her stuff falls out, spilling all over the floor. She starts to cry. Based on what you have learned, do you think she has OCD? Why or why not? What else would you want to know before reaching a conclusion? If she has OCD, is it because she has inherited the disorder? Explain your answer. If she does have OCD, what sorts of treatments should she consider?