7.2 Trauma-Related Disorders

Within a 15-year span, Howard Hughes suffered more than his share of brushes with death—of his own and other people’s. He ran over and killed a pedestrian. He was the pilot in three plane accidents: In the first one, his cheekbone was crushed; in the second, two of his copilots died; in the third, he sustained such extensive injuries to his chest that his heart was pushed to the other side of his chest cavity, and he wasn’t expected to live through the night. Hughes did survive, but he clearly had endured a highly traumatic event.

Some people who experience a traumatic or very stressful event go on to develop a disorder in the DSM-5 category trauma- and stressor-related disorders. According to DSM-5 (American Psychiatric Association, 2013), a trauma-related disorder is marked by four general types of persistent symptoms after exposure to the traumatic event:

- Intrusive re-experiencing of the traumatic event. Intrusion may involve flashbacks that can include illusions, hallucinations, or a sense of reliving the experience, as well as intrusive and distressing memories, dreams, or nightmares of the event.

- Avoidance. The person avoids anything related to the trauma.

- Negative thoughts and mood, and dissociation. Symptoms include persistent negative thoughts about oneself or others (“no one can be trusted”), persistent negative mood (fear, for instance, and difficulty experiencing positive emotions), and dissociation (a sense of feeling disconnected or detached from experiences).

- Increased arousal and reactivity. Arousal and reactivity symptoms include difficulty sleeping, hypervigilance, irritable behavior, angry outbursts, and a tendency to be easily startled (referred to as a heightened startle response).

What Are the Trauma-Related Disorders?

Among the trauma-related disorders in DSM-5 are:

- acute stress disorder, which is the diagnosis when some of the above symptoms emerge immediately after a traumatic event and last between 3 days and 1 month;

- posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), which requires a certain number of symptoms from each of the four groups mentioned above, and the symptoms last more than 1 month.

Most people would agree that Hughes experienced a traumatic event when his airplane crashed and he was severely injured. But what constitutes a traumatic event? The answer, according to DSM-5, is an event that involves:

- directly experiencing actual or threatened serious injury, sexual violation, or death;

- witnessing (in person) actual or threatened serious injury, sexual violation, or death;

- learning of a violent or accidental death or threatened death of a close family member or friend; or

- experiencing extreme exposure to aversive details about the traumatic event (as might occur for first responders).

Traumatic events are more severe than the normal stressful events we all regularly encounter. Examples of traumatic events range from large-scale catastrophes with multiple victims (such as disasters and wars) to unintended acts or situations involving fewer people (such as motor vehicle accidents and life-threatening illnesses) to events that involve intentional and personal violence, such as rape and assault (Briere, 2004). Traumatic events are relatively common: Up to 30% of people will experience some type of disaster in their lifetime, 25% have experienced a serious car accident (Briere & Elliott, 2000), and 20% of women report having been raped during their lifetimes (most frequently by someone they know; Black et al., 2011). Note that according to the DSM-5 definition, emotional abuse is not a traumatic event because it does not involve actual or threatened physical injury or death.

Several factors can affect whether a trauma-related disorder will develop following a traumatic event:

- The kind of trauma. Trauma involving violence—particularly intended personal violence—is more likely to lead to a stress disorder than are natural disasters (Breslau et al., 1998; Briere & Elliott, 2000; Copeland et al., 2007; Dikel et al., 2005).

- The severity of the traumatic event, its duration, and its proximity. Depending on the specifics of the traumatic event, those physically closer to it—nearer to the primary area struck by a tornado, for example—are more likely to develop a stress disorder (Blanchard et al., 2004; Middleton et al., 2002), as are those who have experienced multiple traumatic events (Copeland et al., 2007). For instance, Vietnam veterans were more likely to develop PTSD if they had been wounded or if they had spent more time in combat (Gallers et al., 1988; King et al., 1999). The same is true of veterans who returned from Iraq and Afghanistan: Soldiers who were involved in combat were up to three times more likely to develop PTSD than soldiers who were not exposed to combat (Levin, 2007; Smith et al., 2008).

209

Being exposed to a traumatic event is one component of a trauma-related disorder. The second component is the person’s response to the traumatic event. Although certain types of traumatic events are more likely than others to lead to such disorders, people differ in how they perceive the same traumatic event and how they respond to it. These differences will be based, in part, on previous experience with related events, appraisal of the stressors, and coping style.

What Is Posttraumatic Stress Disorder?

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is diagnosed when people who have experienced a trauma persistently (a) have intrusive re-experiences the traumatic event, (b) avoid stimuli related to the event, (c) have negative changes in thoughts and mood associated with the traumatic event, and (d) have symptoms of reactivity and hyperarousal; all of these symptoms must persist for at least a month (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). These four types of symptoms form the posttrauma criteria for PTSD, as shown in TABLE 7.6, but symptoms may not emerge until months or years after the traumatic event. (Note that TABLE 7.6 applies to adults and children over the age of 6; DSM-5 contains separate criteria for children 6 and younger.)

Note: The following criteria apply to adults, adolescents, and children older than 6 years.

|

| Reprinted with permission from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, (Copyright ©2013). American Psychiatric Association. All Rights Reserved. |

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) A traumatic stress disorder that involves persistent (a) intrusive re-experiencing of the traumatic event, (b) avoidance of stimuli related to the event, (c) negative changes in thoughts and mood, and (d) hyperarousal and reactivity that persist for at least a month.

Some people with PTSD may be diagnosed with a subtype that includes symptoms of dissociation: an altered sense of reality of surroundings or oneself (such as feeling in daze, a sense of the environment’s or one’s body being distorted or “not quite right,” or a sense of time slowing down) (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Stein et al., 2013). TABLE 7.7 presents additional information about PTSD. Case 7.3 describes the experiences of a man with PTSD.

| Prevalence |

|

| Comorbidity |

|

| Onset |

|

| Course |

|

| Gender Differences |

|

| Cultural Differences |

|

| Source: Unless otherwise noted, information in the table is from American Psychiatric Association, 2013. |

CASE 7.3 • FROM THE OUTSIDE: Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

A. C. was a 42-year-old single man, a recent immigrant who, one year before his appearance at the clinic, had walked into his place of work while an armed robbery was taking place. Two men armed with guns hit him over the head, threatened to kill him, tied him up and locked him in a closet with four other employees. He was released from the closet 4 hours later when another employee came in to work. The police were notified and A. C. was taken to the hospital where his head wound was sutured and he was released. For two weeks after the robbery A. C. continued to function as he had before the robbery with no increase in anxiety.

One day while waiting to meet someone on the street he was struck by the thought that he might meet his assailants again. He began to shiver, felt his heart race, felt dizzy, started to sweat and felt that he might pass out. He was brought to an emergency room, examined and released with a referral to victims’ services. His anxiety increased so much that he was unable to return to work because it reminded him of the robbery. He started to have sleep difficulties, waking in the middle of the night to check the front door lock at home. He quit his job and dropped out of school due to his anxiety. He would have flashbacks of the guns that were used in the robbery and started to avoid people on the street who reminded him of the robbers. He began to feel guilty that he had entered the office while the robbery was in progress feeling that he somehow should have known what was occurring. His avoidance extended to the subway, exercising and socializing with friends.

(New York Psychiatric Institute, 2006)

210

211

What Is Acute Stress Disorder?

Acute stress disorder A traumatic stress disorder that involves (a) intrusive re-experiencing of the traumatic event, (b) avoidance of stimuli related to the event, (c) negative changes in thought and mood, (d) dissociation, and (e) hyperarousal and reactivity, with these symptoms lasting for less than a month.

If A. C.’s symptoms had lasted for less than 1 month or if he had sought help from a mental health clinician within a month of the event, A. C. might have been diagnosed with acute stress disorder. Acute stress disorder involves at least 9 of 14 symptoms that fall into five clusters: intrusively re-experiencing the traumatic event, avoiding stimuli related to the event, hyperarousal, negative mood, and dissociation.

As noted in TABLE 7.8, the symptoms occur within 1 month of the trauma (as A. C.’s did), must last at least 3 days but no more than 1 month, and must cause significant distress or impair functioning. Approximately 80% of those with acute stress disorder have symptoms that persist for more than a month, at which point for most people the diagnosis then changes to PTSD (Harvey & Bryant, 2002). Unlike A. C., though, most people who experience trauma do not develop PTSD (National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health, 2005; Shalev et al., 1998).

|

| Reprinted with permission from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, (Copyright ©2013). American Psychiatric Association. All Rights Reserved. |

PTSD and acute stress disorder clearly involve intrusive re-experiencing, avoidance, negative mood, and hyperarousal. But unlike the other disorders we’ve reviewed in this chapter, PTSD and acute stress disorder arise from a clear and consistent cause: a traumatic event. A number of other disorders—one of which we will discuss in the next chapter—appear to share this feature.

212

Could Howard Hughes’s problems have been related to an undiagnosed posttraumatic stress disorder? We don’t know whether Hughes intrusively re-experienced any of his traumatic events or whether he had negative thoughts ormoods related to the traumas, but he did not appear to have obvious avoidance symptoms related to the traumatic experiences: He continued flying after each of his plane accidents. He did have symptoms of increased arousal, such as irritability, hypervigilance, difficulty concentrating, and sleep problems, but these symptoms are better explained by his OCD and drug use. There is no clear evidence that Hughes suffered from PTSD.

213

Understanding Trauma-Related Disorders: PTSD

We focus here on PTSD because more than three-quarters of people with acute stress disorder go on to develop PTSD (see TABLE 7.7), the symptoms of PTSD—almost by definition—last longer than those of acute stress disorder, and most research on trauma-related disorders focuses on PTSD.

Neurological Factors

The neurological factors that contribute to PTSD include overly strong sympathetic nervous system reactions and abnormal hippocampi. In addition, the neurotransmitters norepinephrine and serotonin have been implicated in the disorder, and there is evidence that genes contribute to (but by no means determine) the likelihood that experiencing trauma will result in PTSD.

Brain Systems

Research has often shown that people who suffer from PTSD have sympathetic nervous systems that react unusually strongly to cues associated with their traumatic experience. The cues can cause sweating or a racing heart (Orr et al., 1993, 2002; Prins et al., 1995). Furthermore, the changes in heart rate are distinct from the changes found in control participants who have been asked to pretend to have PTSD (Orr & Pitman, 1993); thus, PTSD patients react more strongly to the relevant cues than would be expected if they did not have a disorder.

In addition, the hippocampus apparently must work harder than normal in PTSD patients when they try to remember information, as shown by the fact that this brain structure is more strongly activated in these patients during memory tasks than in control participants (Shin et al., 2004). This is important because this brain structure plays a crucial role in storing information in memory (Squire & Kandel, 2000), and thus an impaired hippocampus should impair memory. And, in fact, as expected, PTSD patients have trouble recalling autobiographical memories (McNally et al., 1995).

Note that correlation does not imply causation; perhaps the brain abnormality predisposes people to PTSD, or perhaps PTSD leads to the brain abnormality (McEwen, 2001; Pitman et al., 2001). A twin study provides an important hint about what causes what: In this study, researchers compared the sizes of the hippocampi in veterans who had served in combat and had PTSD with the sizes of hippocampi in their identical twins who had not served in combat and did not have PTSD. The results were clear: In both twins, the hippocampi were smaller than normal (Gilbertson et al., 2002). This finding implies that the trauma did not cause the hippocampi to become smaller, but rather the smaller size is a risk factor (or is correlated with some other factor that produces the risk) that makes a person vulnerable to the disorder.

Neural Communication and Genetics

The neurotransmitter norepinephrine appears to be involved in PTSD. For example, Southwick and colleagues (1993) gave volunteers with and without PTSD a drug that allows norepinephrine levels to surge. When norepinephrine levels became very high, 70% of the PTSD patients had a panic attack, and 40% of them had a flashback to the traumatic event that precipitated their disorder; the volunteers who did not have PTSD exhibited minimal effects. Moreover, this drug resulted in more extreme biochemical and cardiovascular effects for the PTSD patients than for the controls.

Various types of evidence indicate that serotonin also plays a role in PTSD. For one, SSRIs can help treat the disorder, and they apparently do so in part by allowing serotonin to moderate the effects of stress (Corchs et al., 2009). In addition, people who have certain alleles of genes that produce serotonin are susceptible to developing the disorder following trauma (Adamec et al., 2008; Grabe et al., 2009).

214

However, research has shown that the effects of such genes may depend on a combination of factors, such as stressful environmental events in combination with low social support—and the same factors that affect whether people develop PTSD also affect whether they develop major depressive disorder (Kilpatrick et al., 2007; Sartor et al., 2012). Moreover, genes appear either to play a smaller role than the environment in predicting PTSD (McLeod et al., 2001) or are relevant only in the context of complex interactions between genes and environment (Broekman et al., 2007).

Psychological Factors: History of Trauma, Comorbidity, and Conditioning

Psychological factors that exist before a traumatic event occurs affect whether a person will develop PTSD. Such factors include the beliefs the person has about himself or herself and the world. Two specific beliefs that can make a person vulnerable to developing PTSD are considering yourself unable to control stressors (Heinrichs et al., 2005; Joseph et al., 1995) and the conviction that the world is a dangerous place (Keane, Zimering, & Caddell, 1985; Kushner et al., 1992).

People can be vulnerable to developing PTSD for a variety of other reasons. For example:

- by coping with a traumatic event by dissociating (disrupting the normal processes of perception, awareness, and memory; Shalev et al., 1996);

- by having severe mental disorders such as bipolar disorder (see Chapter 5) or schizophrenia (Chapter 12);

- by having some type of anxiety disorder (Copeland et al., 2007), perhaps because most anxiety disorders involve hyperarousal and hypervigilance—which may lead people to respond to traumatic events in ways that promote a stress disorder; and

- by having experienced a prior traumatic event (for example, having been assaulted and then, years later, living through a hurricane).

After the traumatic event, classical conditioning and operant conditioning may help to explain how the person learns to avoid triggering PTSD attacks; such explanations parallel those for such behavior in anxiety disorders (Mowrer, 1939; see Chapter 6). In terms of classical conditioning, the traumatic stress is the unconditioned stimulus, and both internal sensations and external objects or situations can become conditioned stimuli, which in turn can come to induce powerful and aversive conditioned emotional responses (Keane, Zimmering, & Caddell, 1985). Thus, when a situation is similar to the traumatic one, it induces reactions that are aversive, leading the person to avoid the situation. In terms of operant conditioning, behaving in ways that avoid triggering PTSD symptoms is negatively reinforced. In addition, drugs and alcohol can temporarily alleviate symptoms; such substance use is also negatively reinforced, which explains why people with PTSD have a higher incidence of substance use disorders than do people who experienced a trauma but did not go on to develop PTSD (Chilcoat & Breslau, 1998; Jacobsen et al., 2001).

215

Social Factors: Socioeconomic Factors, Social Support, and Culture

Social factors—both before a traumatic event and afterward—also help determine whether a person will develop PTSD after a trauma. As with other stressors in life, socioeconomic factors can influence a person’s ability to cope. People who face severe financial challenges—who aren’t sure whether they’ll be able to feed, clothe, and house themselves or their families—have fewer emotional resources available to cope with a traumatic event and so are more likely than more financially fortunate people to develop PTSD after a trauma (Mezey & Robbins, 2001).

In addition, socioeconomically disadvantaged people may be more likely to experience trauma (Breslau et al., 1998; Himle et al., 2009). For instance, poorer people are more likely to live in high-crime areas and are therefore more likely to witness crimes or become crime victims (Norris et al., 2003).

On a more hopeful note, people who receive support from others after a trauma have a lower risk of developing PTSD (Kaniasty & Norris, 1992; Kaniasty et al., 1990). For example, military servicemen and women who have experienced trauma during their service have a lower risk of developing PTSD if they have strong social support upon returning home (Jakupcak et al., 2006; King et al., 1999).

Finally, even when a person does develop PTSD, his or her surrounding culture can help determine which PTSD symptoms are more prominent. Cultural patterns might “teach” one coping style rather than another (Marsella et al., 1996). For example, Hurricane Paulina in Mexico and Hurricane Andrew in the United States were about equal in force, but the people who developed PTSD afterward did so in different ways (after controlling for the severity of a person’s trauma): Mexicans were more likely to have intrusive symptoms, such as flashbacks about the hurricane and its devastation, whereas Americans were more likely to have arousal symptoms, such as an exaggerated startle response or hypervigilance (Norris et al., 2001). A similar finding was obtained from a study comparing Hispanic Americans to European Americans after Hurricane Andrew (Perilla et al., 2002).

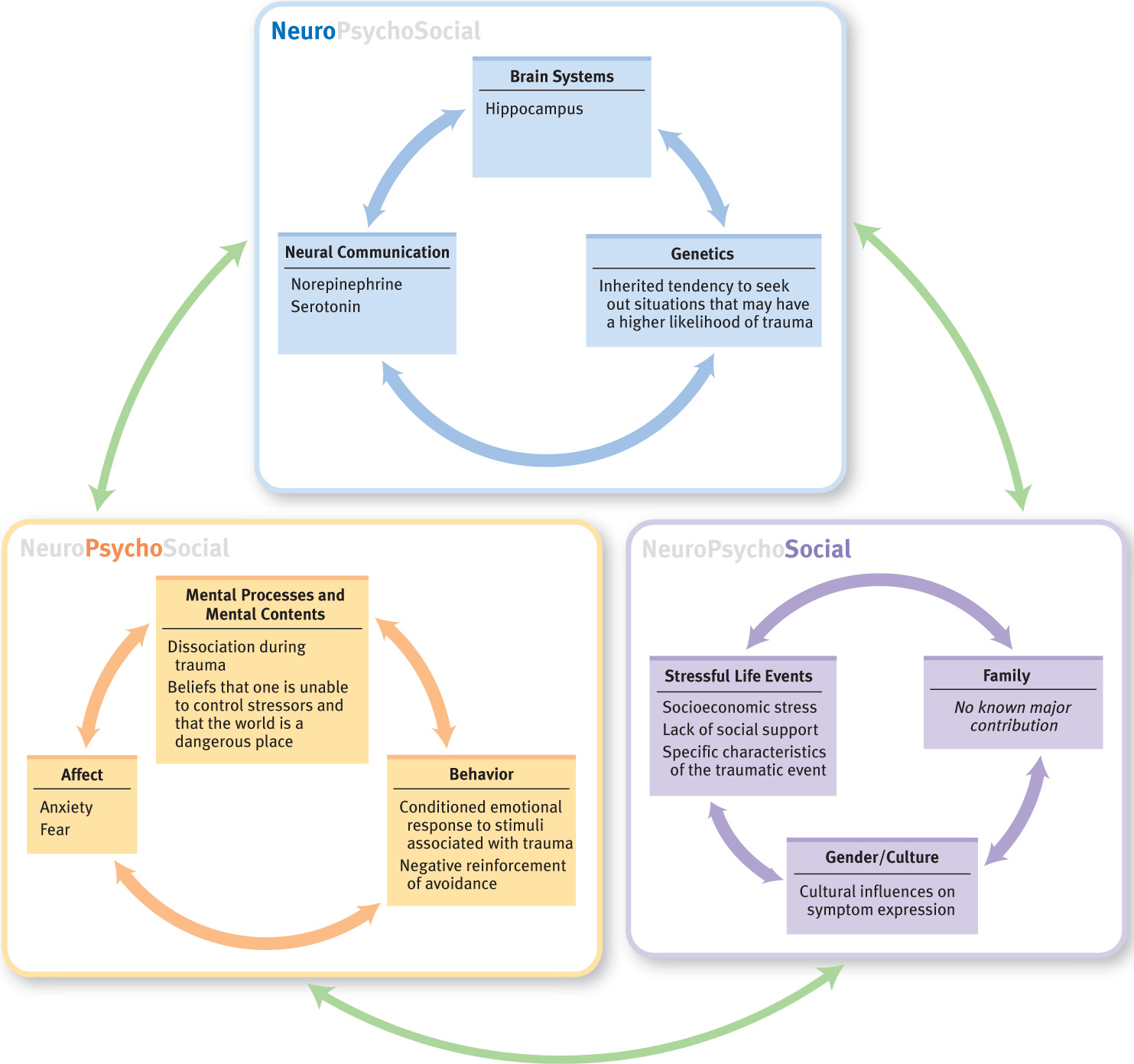

Feedback Loops in Understanding Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

ONLINE

Neurological factors can make some people more vulnerable to developing PTSD after a trauma (van Zuiden et al., 2011). For example, in a study of people who were training to be firefighters, trainees who had a larger startle response to loud bursts of noise (which indicates a very reactive sympathetic nervous system) at the beginning of training were more likely to develop PTSD after a subsequent fire-related trauma (Guthrie & Bryant, 2005). In another study, researchers found that willingness to volunteer for combat and to accept riskier assignments is partly heritable (neurological factor; Lyons et al., 1993). This heritability may involve the dimension of temperament called novelty seeking (see Chapter 2). Someone high in novelty seeking pursues activities that are exciting and very stimulating, and a person with this characteristic may be more likely to volunteer for risky assignments (psychological factor), increasing the chance of encountering certain kinds of trauma. This means that neurological factors can influence both psychological and social factors, which in turn can increase the risk of trauma. At the same time, when a traumatic event is more severe (social factor), other types of factors are less important in influencing the onset of PTSD (Keane & Barlow, 2002). Furthermore, ways of viewing the world and other personality traits (psychological factors) can influence the level of social support that is available to a person after suffering trauma (social factor). Figure 7.2 illustrates these factors and their feedback loops.

216

Treating Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

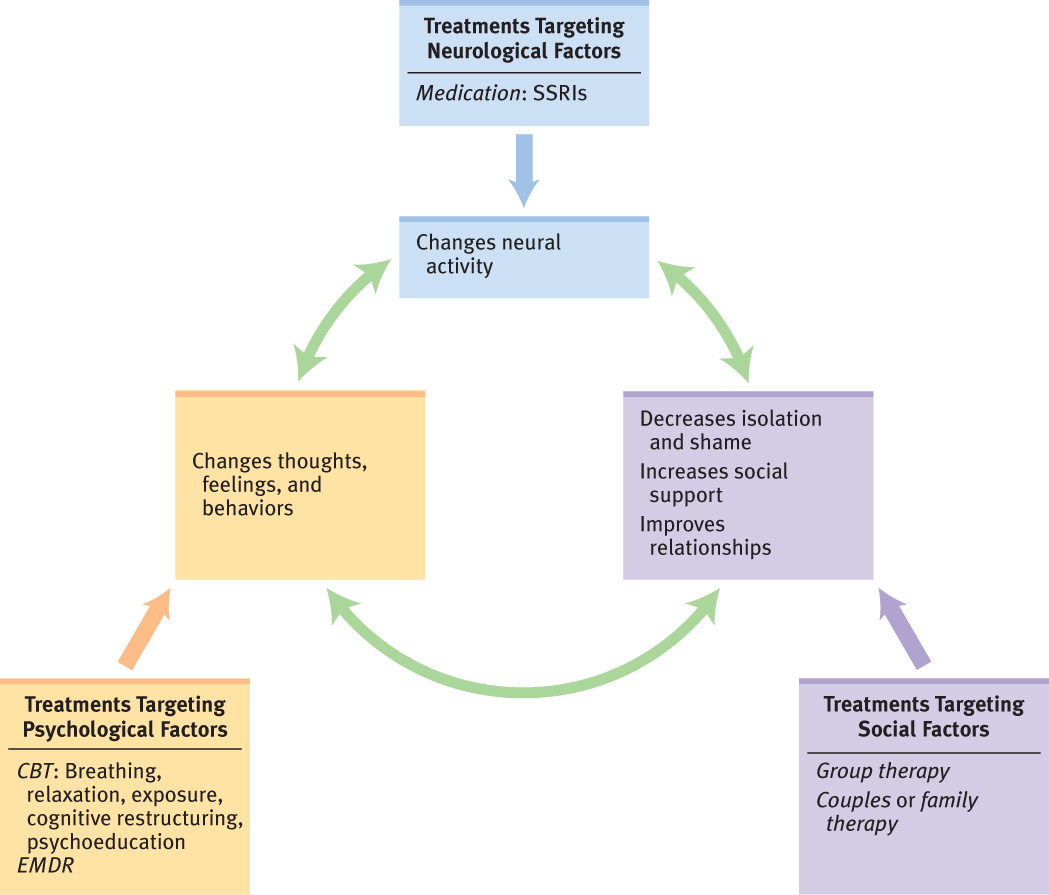

As usual, when a treatment is successful, changes in one factor affect the other factors.

217

Targeting Neurological Factors: Medication

The SSRIs sertraline (Zoloft) and paroxetine (Paxil) are the first-line medications for treating the symptoms of PTSD (Brady et al., 2000; Stein, Seedat, et al., 2000). An advantage of SSRIs is that these medications can also help reduce comorbid symptoms of depression (Hidalgo & Davidson, 2000)—which is important because many people with PTSD also have depression. However, as with anxiety disorders, when people discontinue the medication, the symptoms may return. This is why medication is not usually the sole treatment for PTSD but rather is combined with treatment that directly addresses psychological and social factors (Rosenbaum, Arana et al., 2005).

Targeting Psychological Factors

Treatments that target psychological factors generally employ a combination of behavioral methods and cognitive methods, which—separately or in combination—are about equally effective (Keane & Barlow, 2002; Schnurr et al., 2007; Tarrier et al., 1999).

Behavioral Methods: Exposure, Relaxation, and Breathing Retraining

Someone who has PTSD may go to unreasonable lengths to avoid stimuli associated with the trauma. This is why treatment aims to increase a sense of control over PTSD symptoms and to decrease avoidance. Just as exposure is used to decrease avoidance associated with anxiety disorders, it is used to treat PTSD: Exposure aims to induce habituation and to reduce the avoidance of internal and external cues associated with the trauma (Bryant & Harvey, 2000; Keane & Barlow, 2002). In this case, the specific stimuli in an exposure hierarchy are those associated with the trauma. As the person becomes less aroused and fearful of these stimuli and avoids them less, mastery and control increase. To help with anxiety and reduce arousal symptoms, relaxation and breathing retraining are often included in treatment. Exposure can also be useful in preventing PTSD for people who, in the days following a trauma, have some symptoms of PTSD (Shalev et al., 2012).

CURRENT CONTROVERSY

Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) Treatment for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

Eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) is a widely used but debated psychological treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). The treatment rests on the idea that the symptoms of PTSD arise from the inability to process adequately the images and cognitions that arise when a person experiences a traumatic event (Shapiro, 2001). The treatment contains elements of both psychodynamic and cognitive-behavior therapy, and it was originally designed to help decrease negative emotions associated with traumatic memories (Shapiro & Maxfield, 2002). The phase of the treatment most similar to exposure therapy has the client think about the disturbing visual images or beliefs about the trauma while “moving the eyes from side to side for 15 or more seconds” as the therapist moves his or her fingers back and forth (Shapiro & Maxfield, 2002, p. 937).

On the one hand, EMDR has received enough research support to be considered one of a handful of treatments for PTSD that research suggests is effective (Perkins & Rouanzoin, 2002). However, what remains controversial is whether EMDR imparts any benefit above and beyond standard exposure therapy. Randomized trials comparing EMDR to exposure therapies have found little to no differences in outcomes for the two treatments (Ironson et al., 2002; Lee et al., 2002; Power et al., 2002; Taylor et al., 2003). From the perspective of a patient, the data suggest that the treatment works. But thinking about it from an ethical perspective, if EMDR does not lead to a better outcome than CBT, is the expensive training and certification required to practice the treatment warranted? In addition, some might argue that the eye movements increase the public’s positive perception of the procedure as a medical treatment, even though there is no good evidence that eye movements enhance the benefit.

CRITICAL THINKING As a consumer, would you be concerned about undergoing a treatment if no one completely understood why all the components are helpful? What about taking a medication when we know that the medication helps the disorder but not exactly how it works?

(Randy Arnau, University of Southern Mississippi)

218

Howard Hughes apparently used exposure with himself, which helped him resist developing PTSD. Before his near-fatal plane crash, he loved to fly. During his convalescence after that plane crash, he grew concerned that he’d become afraid of flying—perhaps because he was worried that stimuli associated with the crash (e.g., things related to planes) would lead to anxiety and flashbacks. Although Howard Hughes was worried about developing a fear of flying, the anxiety about flying—and an avoidance of it—didn’t materialize. Because of his passion for the activity, he pushed himself to get back in the cockpit as soon as he was physically able (Barlett & Steele, 1979), and then he flew repeatedly, successfully undergoing a self-imposed in vivo exposure treatment.

Cognitive Methods: Psychoeducation and Cognitive Restructuring

To reduce the difficult emotions that occur with PTSD, educating patients about the nature of their symptoms (psychoeducation) can be a first step. As patients learn about PTSD, they realize that their symptoms don’t arise totally out of the blue; their experiences become more understandable and less frightening.

In addition, cognitive methods can help patients understand the meaning of their traumatic experiences and the (mis)attributions they make about these experiences and the aftermath (Duffy et al., 2007, Foa et al., 1991, 1999), such as “I deserved this happening to me because I should have walked down a different street.”

Studies have shown that CBT can significantly reduce the number of people who, with time, would have had their diagnosis change from acute stress disorder to PTSD (Bryant et al., 2005, 2006, 2008) and can decrease the risk of PTSD in people who, in the days after a traumatic event, exhibit enough symptoms to meet the criteria for PTSD (Shalev et al., 2012).

Targeting Social Factors: Safety, Support, and Family Education

Because a traumatic event is almost always a social stressor, the early focus of treatment for PTSD is to ensure that the traumatized person is as safe as possible (Baranowsky et al., 2005; Herman, 1992). For instance, in a case that involves a woman with PTSD that arose from domestic abuse, the therapist and patient will spend time reviewing whether the woman is safe from further abuse, and if not, how to make her as safe as possible. For some types of traumatic events (such as combat-related trauma), group therapy—of any theoretical orientation—can provide support and diminish the sense of isolation, guilt, or shame about the trauma or the symptoms of PTSD (Schnurr et al., 2003). Moreover, family or couples therapy can help to educate family members and friends about PTSD and about ways in which they can support their loved one (Goff & Smith, 2005; Sherman et al., 2005).

Feedback Loops in Treating Posttraumatic Stress Disorder

ONLINE

To appreciate the interactive aspects of the neuropsychosocial approach, consider a study of people who developed PTSD after being in traffic accidents (as the driver, passenger, or pedestrian; Taylor et al., 2001). Prior to beginning the treatment, 15 of the 50 participants were taking an SSRI, a TCA, or a benzodiazepine. Treatment consisted of 12 weeks of group CBT that involved psychoeducation about traffic accidents, their aftereffects, and PTSD; cognitive restructuring focused on faulty thoughts (such as overrating the dangerousness of road travel); relaxation training; and imaginal and in vivo exposure. After treatment, participants reported that they experienced less sympathetic nervous system reactivity, such as having fewer “hair-trigger” startle responses. In addition, they avoided the trauma-inducing stimuli less often and had fewer intrusive re-experiences of the trauma. These gains were maintained at the 3-month follow-up. So, an intervention that targets both social factors (group therapy with exposure to external trauma-related stimuli) and psychological factors (cognitive and behavioral interventions to change thinking and behavior) also apparently changed neurological functioning, as indicated by the reports of decreased hyperarousal. This change in turn affected both the person’s thoughts and social interactions. Successful treatments for PTSD that target one or two factors ultimately affect all three. Figure 7.3 illustrates these feedback loops in treatment.

Thinking Like A Clinician

Two friends, Farah and Michelle, came back from winter break. Each had been devastated by personal experiences that occurred during the break. Farah’s house burned down after the boiler exploded; fortunately, everyone was safe. Michelle’s house had also been destroyed in a fire, but the police believed it was set by an “enemy” of her father’s. Months pass, and by the time they go home for summer vacation, one of the friends has developed PTSD. Based on what you have read, which friend do you think developed PTSD, and why? What symptoms might she have and why? Based on what you have read, what do you think would be appropriate treatment for her?

219

220