8.1 Dissociative Disorders

Breuer reported that Anna O. was an extremely bright young woman, prone to “systematic day-dreaming, which she described as her ‘private theatre.’” Anna lived “through fairy tales in her imagination; but she was always on the spot when spoken to, so that no one was aware of it. She pursued this activity almost continuously while she was engaged in her household duties” (Breuer & Freud, 1895/1955, p. 22). These dissociative states, or “absences,” began in earnest when Anna became too weak to care for her father, and they became more prominent after his death in April 1881. In what follows we examine dissociative disorders in more detail and then consider whether Anna’s symptoms would meet the criteria for any of these disorders.

Dissociative Disorders: An Overview

Dissociation may arise suddenly or gradually, and it can be brief or chronic (Steinberg, 1994, 2001). Dissociative symptoms include:

- amnesia, or memory loss, which is usually temporary in dissociative disorders but, in rare cases, may be permanent;

Amnesia Memory loss, which in dissociative disorders is usually temporary but, in rare cases, may be permanent.

- identity problems, in which a person isn’t sure who he or she is or may assume a new identity;

Identity problem A dissociative symptom in which a person is not sure who he or she is or may assume a new identity.

- derealization, in which the external world is perceived or experienced as strange or unreal, and the person feels “detached from the environment” or as if viewing the world through “invisible filters” or “a big pane of glass” (Simeon et al., 2000); and

Derealization A dissociative symptom in which the external world is perceived or experienced as strange or unreal.

- depersonalization, in which the perception or experience of self—either one’s body or one’s mental processes—is altered to the point where the person feels like an observer, as though seeing oneself from the “outside.” People experiencing depersonalization may describe it as feeling is if “under water” or “floating,” “like a dead person,” “as if I’m here but not here,” “detached from my body,” or “like a robot” (Simeon et al., 2000).

Depersonalization A dissociative symptom in which the perception or experience of self—either one’s body or one’s mental processes—is altered to the point that the person feels like an observer, as though seeing oneself from the “outside.”

You may notice that some of these symptoms sound familiar. That’s because all but identity problems are listed among the criteria for PTSD or acute stress disorder (Chapter 7). In fact, as we’ll discuss later in the chapter, trauma is thought to play a major role in dissociative disorders.

225

Anna O. appeared to experience derealization. After her father died, she recounted “that the walls of the room seemed to be falling over” (Breuer & Freud, 1895/1955, p. 23). She also reported having trouble recognizing faces and needing to make a deliberate effort to do so: “‘this person’s nose is such-and-such, his hair is such-and-such, so he must be so-and-so.’ All the people she saw seemed like wax figures without any connection with her” (Breuer & Freud, 1895/1955, p. 26).

Normal Versus Abnormal Dissociation

Experiencing symptoms of dissociation is not necessarily abnormal; occasional dissociating is a part of everyday life (Seedat et al., 2003). For instance, you may find yourself in a class but not remember walking to the classroom. Or, on hearing bad news, you may feel detached from yourself, as if you’re watching yourself from the outside.

In some cases, periods of dissociation are part of religious or cultural rituals (Boddy, 1992). Consider the phenomenon of possession trance observed in some societies: During a hypnotic trance, a kind of spirit is believed to assume control of the person’s body. Later, the person has amnesia for the experience, and is otherwise normal. Moreover, people in different cultures may express dissociative symptoms differently. For example, latah, experienced by people—mostly women—in Indonesia and Malaysia (Bartholomew, 1994), involves fleeting episodes in which the person uses profanity and experiences amnesia and trancelike states. Unlike the typical course with psychosis, the “possessed” person returns to normal after the trance is over.

Dissociative disorders A category of psychological disorders in which consciousness, memory, emotion, perception, body representation, motor control, or identity are dissociated to the point where the symptoms are pervasive, cause significant distress, and interfere with daily functioning.

In some instances, dissociative experiences do indicate a disorder, but not necessarily a dissociative disorder; other psychiatric disorders can involve dissociative symptoms, such as when depersonalization or derealization occurs during a panic attack. DSM-5 reserves the category of dissociative disorders for cases in which consciousness, memory, emotion, perception, body representation, motor control, or identity are dissociated to the point where the symptoms are pervasive, cause significant distress, and interfere with daily functioning. Research findings suggest that pathological dissociation is qualitatively different from everyday types of dissociation, such as “spacing out” (Rodewald et al., 2011; Seedat et al., 2003). Only about 2% of the U.S. population reports having experienced dissociation to the extent that would be considered abnormal (Seedat et al., 2003).

Anna’s dissociative symptoms do appear to have been abnormal; she had dissociations in perception, consciousness, memory, and identity:

Two entirely distinct states of consciousness were present which alternated very frequently and without warning and which became more and more differentiated in the course of the illness. In one of these states she recognized her surroundings; she was melancholy and anxious, but relatively normal. In the other state she hallucinated and was “naughty”—that is to say, she was abusive, used to throw the cushions at people,…tore buttons off her bedclothes and linen with those of her fingers which she could move, and so on. At this stage of her illness if something had been moved in the room or someone had entered or left it [during her other state of consciousness] she would complain of having “lost” some time and would remark upon the gap in her train of conscious thoughts.

226

These “absences” had already been observed before she took to her bed; she [would] stop in the middle of a sentence, repeat her last words and after a short pause go on talking. These interruptions gradually increased till they reached the dimensions that have just been described…. At the moments when her mind was quite clear she would complain of the profound darkness in her head, of not being able to think,…of having two selves, a real one and an evil one which forced her to behave badly, and so on.

(Breuer & Freud, 1895/1955, p. 24)

Anna’s dissociative experiences were clearly beyond normal: They were pervasive and interfered with her daily functioning.

Types of Dissociative Disorders

DSM-5 defines three types of specific dissociative disorders, described in the following sections: dissociative amnesia, depersonalization-derealization disorder, and dissociative identity disorder.

Dissociative Amnesia

Anna’s native language was German, but as her condition began to worsen while she was nursing her father, she started to speak only English (a language in which she was also fluent). She developed complete amnesia for speaking the German language. Let’s examine why her amnesia for speaking in her native language might be considered dissociative.

What Is Dissociative Amnesia?

Dissociative amnesia A dissociative disorder in which the sufferer has significantly impaired memory for important experiences or personal information that cannot be explained by ordinary forgetfulness.

Dissociative amnesia is a dissociative disorder in which the sufferer has significantly impaired memory for autobiographical information—important experiences or personal information—that is not consistent with ordinary forgetfulness (see TABLE 8.1). The experiences or information typically involve traumatic or stressful events, such as occasions when the patient has been violent or tried to hurt herself or himself; the amnesia can come on suddenly. For example, soon after a bloody and dangerous battlefield situation, a soldier may not be able to remember what happened.

|

| Reprinted with permission from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, (Copyright ©2013). American Psychiatric Association. All Rights Reserved. |

To qualify as dissociative amnesia, the memory problem cannot be explained by a medical disorder, substance use, or other disorders that have dissociation as a key symptom; as with all other dissociative disorders, it must also significantly impair functioning or cause distress (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). In Anna’s case, her amnesia for speaking German could not really be considered as the loss of personal information but conceivably could be construed as the loss of an important experience and couldn’t be explained by another disorder—and her father’s illness and declining health had been extremely stressful for her.

The memory problems in dissociative amnesia can take any of several forms:

- Localized amnesia, in which the person has a memory gap for a specific period of time, often a period of time just prior to the stressful event, as did Mrs. Y in Case 8.1. This is the most common form of dissociative amnesia (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

- Selective amnesia, in which the person can remember only some of what happened in an otherwise forgotten period of time. For instance, a soldier may forget about a particularly traumatic battlefield skirmish but remember what he and another person spoke about between phases of this skirmish.

- Generalized amnesia, in which the person can’t remember his or her entire life. Although common in television shows and films, this type of amnesia is, in fact, extremely rare (Spiegel et al., 2011).

227

CASE 8.1 • FROM THE OUTSIDE: Dissociative Amnesia

Mrs. Y, a 51-year-old married woman…had a two-year history of severe depressive episodes with suicidal ideation, and reported total loss of memory for 12 years of her life…from the age of 37 to 49. [The amnesia began at age 49 when] she had had a car accident from which she sustained a very minor injury, but no loss of consciousness [nor any] posttraumatic stress symptoms…. She remembered what happened in the accident, and immediately preceding it, but suddenly had total loss of memory for the previous 12 years.

Mrs. Y had no problems recalling events which had occurred since the accident. She also had good autobiographical memory for her life events up to the age of 37.

Her parents and her grown-up children had told her that the…12 years were painful for her. They would not tell her why, because they thought it would distress her even more. She was not only amnesic for these reputedly painful events, [but was unable] to recognize any of the friends she had made during that time. This included her present man friend, who was the passenger in her car at the time of the accident. Her family had told Mrs. Y that this gentleman (Mr. C) had been courting her for six years prior to the accident.

(Adapted from Degun-Mather, 2002, pp. 34–35)

In addition, some people with dissociative amnesia may have a subtype: dissociative fugue, which involves sudden, unplanned travel and difficulty remembering the past—which in turn can lead sufferers to be confused about who they are and sometimes to take on a new identity. Such a fugue typically involves generalized amnesia. In some cultures, people can develop a related set of symptoms referred to as a running syndrome. Although this condition has some symptoms that are similar to those of a dissociative fugue, it typically involves a sudden onset of a trancelike state and behavior such as running or fleeing, which leads to exhaustion, sleep, and subsequent amnesia for the experience. Running syndromes include (American Psychiatric Association, 2000):

- pibloktoq among native Arctic people,

- grisi siknis among the Miskito of Nicaragua and Honduras, and

- amok in Western Pacific cultures.

These syndromes have in common with dissociative fugue the symptom of unexpected travel, but amnesia occurs after the running episode is over, so the person doesn’t remember that it happened. In contrast, with dissociative fugue, the memory problem arises during the fugue state, and the person can’t remember his or her past. In addition, other criteria for dissociative amnesia do not necessarily apply to running syndromes. Additional facts about dissociative amnesia are listed in TABLE 8.2.

| Prevalence |

|

| Comorbidity |

|

| Onset |

|

| Course |

|

| Gender Differences |

|

| Cultural Differences |

|

| Source: Unless otherwise noted, the source is American Psychiatric Association, 2013. For more information see the Permissions section. |

228

People with dissociative amnesia typically are unaware—or only minimally aware—of their memory problems (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Some people may spontaneously remember forgotten experiences or information, particularly if their amnesia developed in response to a traumatic event and they leave the traumatic situation behind (such as occurs when a soldier with combat-related localized amnesia leaves the battlefield). Anna O. recovered her ability to speak German at the end of her treatment with Dr. Breuer, after she reenacted a traumatic nightmare that she’d had at her father’s sickbed (and that marked the start of her problems).

Understanding Dissociative Amnesia

The following sections apply the neuropsychosocial approach as a framework for understanding the nature of dissociative amnesia. However, because the disorder is so rare, not much is known about either the specific factors that give rise to it or how those factors might influence each other.

Neurological Factors: Brain Trauma?

Neurological factors are clearly involved in cases of amnesia that arise following brain injury, such as that suffered in a car accident (Piper & Merskey, 2004a). However, when amnesia follows brain injury, it is not considered to be dissociative amnesia. Neurological factors that may contribute to dissociative amnesia are less clear-cut.

Some researchers have suggested that dissociative amnesia may result in part from damage to the hippocampus, which is critically involved in storing new information about events in memory. These researchers assume that periods of prolonged stress affect the hippocampus so that it does not operate well when the person is highly aroused (Joseph, 1999). The arousal—which typically accompanies a traumatic event—will impair the ability to store new information about that event. Later, this process would lead to the symptoms of dissociative amnesia for that event.

However, the idea that damage to the hippocampus underlies dissociative amnesia cannot explain all cases of the disorder. Because such damage would prevent information from being stored in the first place, the subsequent amnesia would not be reversible: There would be no way to retrieve the memories later because the memories would not exist (Allen et al., 1999). That is, the hippocampus is a critical gate-keeper of memory; without it, new information about facts cannot be stored. If damage to the hippocampus prevents new information from being stored, then such information is not available for later retrieval (even if the hippocampus itself recovers). Given that many cases of dissociative amnesia are characterized by “recovered” memories, it is not clear which brain systems would be involved.

Psychological Factors: Disconnected Mental Processes

The earliest theory of the origins of dissociative amnesia was dubbed the dissociation theory (Janet, 1907). Dissociation theory posits that very strong emotions (which may occur in response to a traumatic stressor) narrow the focus of attention and also disorganize cognitive processes, which prevent them from being integrated normally. According to this theory, the poorly integrated cognitive processes allow memory to be dissociated from other aspects of cognitive functioning, leading to dissociative amnesia. At best, the theory provides only a broad explanation for dissociative amnesia; it does not outline specific mechanisms to account for the dissociation and possible later reintegration of memory.

In contrast, neodissociation theory (Hilgard, 1994; Woody & Bowers, 1994) proposes that an “executive monitoring system” in the brain (specifically, the frontal lobes) normally coordinates various cognitive systems, much like a chief executive officer coordinates the various departments of a large company. However, in some circumstances (such as while a person is experiencing a traumatic event), the various cognitive systems can operate independently of the executive monitoring system. When this occurs, the executive system no longer has access to the information stored or processed by the separate cognitive systems. Memory thus operates as an independent cognitive system, and an “amnestic barrier” arises between memory and the executive system. This barrier causes the information in memory to be cut off from conscious awareness—that is, dissociated. Aspects of both dissociation and neodissociation theories have received some support from research (Green & Lynn, 1995; Hilgard, 1994; Kirsch & Lynn, 1998).

229

Social Factors: Indirect Effects

Many traumatic events result from social interactions, such as combat and abuse. These kinds of social traumas are likely to contribute to dissociative disorders, particularly dissociative amnesia. In fact, people with a dissociative disorder report childhood physical or sexual abuse almost three times more often than do people without a dissociative disorder (Foote et al., 2006). However, some researchers point out that traumatic events can also induce anxiety, which can lead people to have dissociative symptoms. Thus, traumatic events may not directly cause dissociative symptoms such as amnesia; rather, such events may indirectly lead to such symptoms by triggering anxiety (Cardeña & Spiegel, 1993; Kihlstrom, 2001).

As noted in TABLE 8.2, some researchers propose that dissociative amnesia is a disorder of modern times because there are no written accounts of its occurring before 1800 in any culture (Pope et al., 2007).

In sum, dissociative amnesia in the absence of physical trauma to the brain is extremely rare, which makes research on etiology and treatment similarly rare. Although researchers have proposed theories about why and how dissociative amnesia arises, these theories address dissociation generally; dissociative amnesia as a disorder is not well understood. These same deficiencies—a scarcity of research and vague theories that do not adequately characterize the specific mechanisms—also limit our understanding of the other dissociative disorders.

Depersonalization-Derealization Disorder

Depersonalization-derealization disorder A dissociative disorder, the primary symptom of which is a persistent feeling of being detached from one’s mental processes, body, or surroundings.

Like many other people, you may have experienced depersonalization or derealization. This does not mean that you have depersonalization-derealization disorder. A persistent feeling of being detached from one’s mental processes, body, or surroundings is the key symptom of depersonalization-derealization disorder; people who have this disorder may experience depersonalization only, derealization only, or they may have both dissociative symptoms.

What Is Depersonalization-Derealization Disorder?

People afflicted with depersonalization-derealization disorder may feel “detached from my body” or “like a robot,” or their surroundings may feel surreal, but they do not believe that they are truly detached, that they are actually a robot, or that their surroundings have actually become surreal. They still recognize reality. (In contrast, people who have a psychotic disorder may feel and believe such things; see Chapter 12.) In addition, people with depersonalization-derealization disorder may not react emotionally to events; they may feel that they don’t control their behavior and are just being swept along by what is happening around them. These symptoms may lead sufferers to feel that they are “going crazy.” TABLE 8.3 presents the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria; symptoms meet the criteria for the disorder only when they occur independently of anxiety symptoms and when they impair functioning or cause significant distress. TABLE 8.4 provides more facts about depersonalization-derealization disorder, and Case 8.2 shares the story of Mr. E, who has the disorder.

|

| Reprinted with permission from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, (Copyright ©2013). American Psychiatric Association. All Rights Reserved. |

| Prevalence |

|

| Comorbidity |

|

| Onset |

|

| Course |

|

| Gender Differences |

|

| Source: Unless otherwise noted, the source is American Psychiatric Association, 2013. |

230

CASE 8.2 • FROM THE OUTSIDE: Depersonalization-Derealization Disorder

[Mr. E] was a 29-year-old, single man, employed as a journalist, who reported a 12-year history of [depersonalization-derealization] disorder. He described feeling detached from the world as though he was living “inside a bubble” and found it difficult to concentrate since he felt as though his brain had been “switched off.” His body no longer felt solid and he could not feel himself walking on the ground. The world appeared two-dimensional and he reported his sense of direction and spatial awareness to be impaired. He described himself as having lost his “sense of himself” and felt that he was acting on “auto-pilot.” He also reported symptoms of depression and some symptoms of OCD, which took the form of counting and stepping on cracks in the pavement, although he did not report the latter as a problem.

Prior to the onset of his [depersonalization-derealization disorder], he experienced transient [depersonalization] symptoms when intoxicated with cannabis. At the age of 17, he started at a new school and felt very anxious and experienced [depersonalization] symptoms when not under the influence of cannabis…. He described the first time this happened as “terrifying” since he felt he had “gone into another world.” He reported difficulty with breathing and believed he may have a brain tumor or that his “brain was traumatized into a state of panic.” From the age of 17 to 19, the episodes of [depersonalization] became more frequent until they became constantly present. He reports the symptoms as “enormously restricting” his life in that he felt frustrated since he has been “unable to express or enjoy myself.”

(Hunter et al., 2003, Appendix A, pp. 1462–1463)

231

Understanding Depersonalization-Derealization Disorder

Researchers are beginning to chart the factors that contribute to depersonalization-derealization disorder—but again, because the disorder is so rare, there are relatively few studies of it.

Neurological Factors

Studies converge in providing evidence that depersonalization-derealization disorder arises, at least in part, from disruptions of emotional processing (Sierra et al., 2002). For example, when patients with this disorder viewed faces with highly emotional expressions, activity in the limbic system decreased rather than increased, as it does for most people—and this occurred in response to both very happy and very sad expressions (Lemche et al., 2007). This study also showed that the patients had unusually high levels of activity in the frontal lobes when viewing such facial expressions. This is important because the frontal lobes can suppress emotional responses, which might produce the sense of emotional detachment that such patients report. Such an effect might also explain why brain areas involved in emotion are not activated when patients with depersonalization-derealization disorder try to remember words that name emotions, whereas these brain areas are activated when normal control participants perform this task (Medford et al., 2006).

A PET study of patients with depersonalization-derealization disorder found unusual levels of activation (either too high or too low) in parts of the brain specifically involved in various phases of perception—the temporal and parietal lobes (Simeon et al., 2000). The researchers noted that these findings are consistent with the idea that depersonalization-derealization disorder involves dissociations in perception.

In addition, patients with depersonalization-derealization disorder do not produce normal amounts of norepinephrine. In fact, the more strongly they exhibit symptoms of the disorder, the less norepinephrine they apparently produce (as measured in their urine; Simeon, Guralnick, et al., 2003). Norepinephrine is associated with activity of the autonomic nervous system, and thus this finding is consistent with the idea that these patients have blunted responses to emotion.

Psychological Factors: Cognitive Deficits

Patients with depersonalization-derealization disorder have cognitive deficits that range from problems with short-term memory to impaired spatial reasoning, but the root cause of these difficulties appears to lie with attention: These patients cannot easily focus and sustain their attention (Guralnik et al., 2000, 2007). This is consistent with neuroimaging studies that reveal decreased activity in parts of the brain involved in perception. However, it is not clear whether the attentional problems are a cause or an effect of the disorder: On one hand, if a person were feeling disconnected from the world, he or she would not pay normal attention to objects and events; on the other hand, if a person had such attentional problems, this could contribute to feeling disconnected from the world. Moreover, given that many patients with depersonalization-derealization disorder also have depression or an anxiety disorder (Baker et al., 2003), it is not clear whether the problems with attention are specifically related to depersonalization-derealization disorder or arise from the comorbid disorder.

Social Factors: Childhood Emotional Abuse

We noted earlier that stressful events (often a result of social interactions) can trigger depersonalization-derealization disorder. Moreover, a specific type of social stressor—severe and chronic emotional abuse experienced during childhood—seems to play a particularly important role in triggering depersonalization-derealization disorder (Simeon et al., 2001), although it is not clear why such abuse might lead to depersonalization-derealization disorder only in some cases. Once the disorder develops, the perception of threatening social interactions and new environments can exacerbate its symptoms (Simeon, Knuteska, et al., 2003). For instance, if Mr. E in Case 8.2 had a fight with a friend, his depersonalization symptoms would probably become worse during the fight.

232

ONLINE

Feedback Loops in Understanding Depersonalization-Derealization Disorder

One hypothesis for how depersonalization-derealization disorder arises is as follows: First, a significant stressor (often a social factor) elicits neurological events (partly in the frontal lobes) that suppress normal emotional responses (Hunter et al., 2003; Sierra & Berrios, 1998; Simeon, Knutelska, et al., 2003). Following this, the disconnection between the intensity of the perceived stress and the lack of arousal may lead these patients to feel “unreal” or that their surroundings are unreal, which they may then attribute (a psychological factor) to being mentally ill (Baker, Earle, et al., 2007; Hunter et al., 2003). And, in turn, the incorrect and catastrophic attributions that the patients make about their symptoms can lead to further anxiety (as occurs with panic disorder). The attributions can also lead to further depersonalization or derealization symptoms. Patients then become extremely sensitive to and hypervigilant for possible symptoms of “unreality” and come to fear that the symptoms indicate that they are “going crazy.” They may also avoid situations likely to elicit the symptoms.

Dissociative Identity Disorder

Dissociative identity disorder, once known as multiple personality disorder, may be the most controversial of all DSM-5 disorders. First we examine what dissociative identity disorder is, then some criticisms of the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria, and then factors that may contribute to the disorder. In the process of examining these factors, we delve into the controversy about the disorder.

What Is Dissociative Identity Disorder?

Dissociative identity disorder (DID) A dissociative disorder characterized by the presence of two or more distinct personality states, or an experience of possession trance, which gives rise to a discontinuity in the person’s sense of self and agency.

The central feature of dissociative identity disorder (DID) is the presence of two or more distinct “personality states” (sometimes referred to as alters) or an experience of being “possessed,” which leads to a discontinuity in the person’s sense of self and ability to control his or her functioning. Such a discontinuity can affect any aspect of functioning, including mood, behavior, consciousness, memory, perception, thoughts, and sensory-motor functioning.

In some cases, these personality states have separate characteristics and history, and they take turns controlling the person’s behavior. For example, a person with this disorder might have an “adult” personality state that is very responsible, thoughtful, and considerate and a “child” personality state that is irresponsible, impulsive, and obnoxious. Each personality state can have its own name, mannerisms, speaking style, and vocal pitch that distinguish it from others. Some personality states report being unaware of the existence of others, and thus they experience amnesia (because the memory gaps are longer than ordinary forgetting).

Perhaps the most compelling characteristic of personality states is that, for some patients, each personality state can have unique medical problems and histories: One might have allergies, medical conditions, or even EEG patterns that the others do not have (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). Stressful events can trigger a switch of personality states, whereby the one that was dominant at one moment recedes and another becomes the dominant. Although the number of personality states that have been reported ranges from 2 to 100, most people diagnosed with DID have 10 or fewer (American Psychiatric Association, 2000).

233

In other cases, the personality states may be less obvious and other personality states only emerge for brief periods of time. Such patients may report feeling detached from themselves (as if they were observing themselves), hearing voices (such as children crying), or having waves of strong emotion—out of the blue—over which they have no control. TABLE 8.5 lists the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for DID, and TABLE 8.6 provides further information about the disorder.

|

| Reprinted with permission from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, (Copyright ©2013). American Psychiatric Association. All Rights Reserved. |

| Prevalence |

|

| Comorbidity |

|

| Onset |

|

| Course |

|

| Gender Differences |

|

| Cultural Differences |

|

| Source: Unless otherwise noted, the source is American Psychiatric Association, 2013. |

People with DID may not be able to remember periods of time in the past (such as getting married) or skills they learned (such as how to drive a car or aspects of their job), or they may discover “evidence” of actions they don’t remember performing, such as finding new clothes in their closet or furniture moved. Moreover, they may find themselves somewhere and not know how they got there (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

For some people, a personality state takes the form of “possession” by a spirit, ghost, or another person who has taken control. In such cases, patients may act and speak as if they were the entity who has “taken over,” such as the spirit of someone in the community who died. (However, when possession is part of a spiritual practice, these symptoms would be considered normal, and a diagnosis of DID would not be made.) To qualify for a diagnosis of DID, the additional personality states must impair functioning or be significantly distressing; in fact, 70% of people with this disorder attempt suicide (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Case 8.3 presents the personality states of someone with DID, which was previously called multiple personality disorder (MPD).

234

CASE 8.3 • FROM THE INSIDE: Dissociative Identity Disorder

In Robert B. Oxnam’s memoir, A Fractured Mind, his various personality states (11 in all) tell their stories. The following excerpts present recollections from 2 of the alters, beginning with Robert:

This is Robert speaking. Today, I’m the only personality who is strongly visible inside and outside…. Fifteen years ago, I rarely appeared on the outside, though I had considerable influence on the inside; back then, I was what one might call a “recessive personality.”

Although [Bob, another alter] was the dominant MPD personality for thirty years, [he] did not have a clue that he was afflicted by multiple personality disorder until 1990, the very last year of his dominance. That was the fateful moment when Bob first heard that he had an “angry boy named Tommy” inside of him.

(Oxnam, 2005, p. 11)

Another alter, Bob, recounts:

There were blank spots in my memory where I could not recall anything that happened for blocks of time. Sometimes when a luncheon appointment was canceled, I would go out at noon and come back at 3 P.M. with no knowledge of where I had been or what I had done. I returned tired, a bit sweaty, but I quickly showered and got back to work. Once, on a trip to Taiwan, a whole series of meetings was canceled because of a national holiday; I had zero memory of what I did for almost three days, but I do recall that, after the blank spot disappeared, I had a severe headache and what seemed to be cigarette burns on my arm.

(Oxnam, 2005, p. 31).

Criticisms of the DSM-5 Criteria

Significant problems plague the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for DID, including the following (Piper & Merskey, 2004b):

- DSM-5 does not define the separate “personality states”; accordingly, a normal emotional state that emerges episodically—such as periodic angry outbursts—could be considered a “personality state” that is different than the person’s “usual” state. Thus, the criteria permit possibility that normal emotional fluctuations could be considered pathological.

- DID—which is easy to role-play—can be difficult to distinguish from malingering (Labott & Wallach, 2002; Stafford & Lynn, 2002). When people can easily fake symptoms of a disorder, the validity of the disorder as a diagnostic entity can be questioned.

- DID can be difficult to distinguish from rapid-cycling bipolar disorder because both involve sudden changes in mood and demeanor. However, appropriate treatments for bipolar disorder differ from those for DID, which is why accurate diagnosis is important (Piper & Merskey, 2004b).

Some of Anna O.’s dissociative experiences seem similar to those of patients with DID, such as her “naughty” states (for which she had amnesia) and her feeling that she had two selves, a real one and an evil one, which would “take control.”

Understanding Dissociative Identity Disorder

Research findings on various factors associated with DID can be at odds with each other, which only fuels the controversy over the validity of the diagnosis itself. As we shall see, much of the research on, and theorizing about, factors that may contribute to DID hinge on the fact that many people with this disorder report having been severely and chronically abused as children (Lewis et al., 1997; Ross et al., 1991).

Neurological Factors: Alters in the Brain?

One hallmark of DID is that memories acquired by one personality state are not directly accessible to others. However, studies suggest that although alters may report the subjective experience of amnesia, they do, in fact, have access to memories of other alters (Huntjens et al., 2005, 2006, 2007; Kong et al., 2008). Consistent with these findings, researchers have used changes in electrical activity on the scalp to show that the brain responds as if the patient with DID recognizes previously learned words, even when the learning took place when one alter was dominant and the testing occurred when another alter was dominant (Allen & Movius, 2000).

235

Perhaps the key characteristic of DID is that each alter has a different “sense of self.” To the person with DID, it feels as if different personalities “take over” in turn. To explore the neural bases of this phenomenon, Reinders and colleagues (2003) asked 11 DID patients to listen to stories about their personal traumatic history while their brains were scanned using PET. Each patient was scanned once when an alter who was aware of the past trauma was dominant and once when an alter who was not aware of the past trauma was dominant. Two results are of particular interest: First, and most basic, the brain responded differently for the two alters. This alone is evidence that something was neurologically different when the person was in the two states. Second, the traumatic history activated brain areas known to be activated by autobiographical information—but only when the alter that was aware of that information was dominant during the PET scanning.

However, it is difficult to interpret the results of many studies that investigate neurological differences among alters because the studies do not include an appropriate control group (Merckelbach et al., 2002). Researchers have found that hypnosis can alter brain activity (Kosslyn et al., 2000), so it is possible that at least some of the neurological differences between alters reflect a form of self-hypnosis. That is, the person with DID—perhaps unconsciously—hypnotizes himself or herself, which produces different neurological states when different alters come to the fore.

Researchers have also investigated what role genetics might play in DID. Using a questionnaire, a team of researchers assessed the capacity for dissociative experiences in monozygotic and dizygotic twins in the general population (Jang et al., 1998). This questionnaire did not address DID directly, but it did assess the capacity for both “normal” dissociations (such as becoming very absorbed in a television show or a movie) and “abnormal” dissociations (such as not recognizing your face in a mirror). These researchers found that almost half the variation in abnormal dissociations could be attributed to genes.

Psychological Factors

The primary psychological factor associated with DID is hypnotizability: Patients with this diagnosis are highly hypnotizable and can easily dissociate (Bliss, 1984; Frischholz et al., 1990, 1992). That is, they can spontaneously enter a trance state and frequently experience symptoms of dissociation, such as depersonalization or derealization. These abilities play a critical role in a psychologically based theory of DID, described in the upcoming section on feedback loops.

Social Factors: A Cultural Disorder?

Social factors have apparently affected the frequency of diagnosis of DID. DID was rarely diagnosed until 1976 (Kihlstrom, 2001; Lilienfeld et al., 1999; Spanos, 1994). What happened in 1976? The television movie Sybil was aired and received widespread attention. This movie portrayed the “true story” of a woman with DID. The movie apparently affected either patients (who became able to express their distress in this popularized way) or therapists (who became more willing to make the diagnosis) or both. However, years later, it was revealed that the patient who was known as Sybil did not have alters but rather had been encouraged by her therapist to “name” her different feelings as if they were alters; thus, what Sybil’s therapist wrote about the alters was not based on Sybil’s actual experiences (Borch-Jacobsen, 1997; Rieber, 1999).

236

Consistent with the view that DID is a disorder induced by social factors present in some cultures, many countries, such as India and China, have an extremely low or zero prevalence rate of DID (Adityanjee et al., 1989; Draijer & Friedl, 1999; Xiao et al., 2006). In other countries, such as Uganda, people with DID symptoms are considered to be experiencing the culturally sanctioned possession trance, not suffering from DID (van Dujil et al., 2005).

Feedback Loops in Understanding Dissociative Identity Disorder: Two Models for the Emergence of Alters

ONLINE

Two models of dissociative identity disorder—the posttraumatic model and the sociocognitive model—are based on the existence of feedback loops among neurological, psychological, and social factors. However, the two models emphasize the roles of different factors and have different accounts of how the factors influence each other.

The Posttraumatic Model In addition to dissociating or entering hypnotic trances easily, most DID patients have at least one alter that reports having suffered severe, often recurring, physical abuse when young (which would imply a stress response; neurological factor) (Lewis et al., 1997; Ross et al., 1991). This trauma, induced by others (social factor), may increase the ease of dissociating (psychological factor). In fact, children who experienced severe physical abuse later report that during the traumatic events, their minds temporarily left their bodies (which presumably was a way of coping); that is, they dissociated. Putting these observations together, the posttraumatic model proposes that after frequent episodes of abuse with accompanying dissociation, the child’s dissociated state can develop its own memories, identity, and way of interacting with the world, thereby becoming an “alter” (Bremner, 2010; Gleaves, 1996; Putnam, 1989).

Several studies support some aspects of the posttraumatic model. As would be expected from this model, some people with DID do have documented histories of severe physical abuse in childhood (Lewis et al., 1997; Putnam, 1989; Swica et al., 1996) and also report having displayed signs of dissociation in childhood (Lewis et al., 1997). Moreover, these patients report that they either don’t remember being abused or remember very little of it (Lewis et al., 1997; Swica et al., 1996). In addition, girls who were easy to hypnotize and able to dissociate readily were found to be the ones most likely to have been abused physically or sexually (Putnam et al., 1995).

In addition, research on sleep and dissociation may shed light on how DID emerges (Lynn et al., 2012). Specifically, when healthy volunteers are deprived of sleep, they are more likely to experience dissociative symptoms (Giesbrecht et al., 2007). And when patients with dissociative symptoms receive treatment to help improve their sleep, their dissociative symptoms diminish (van der Kloet, Giesbrecht, et al., 2012). When someone’s sleep cycle is altered—perhaps because of a traumatic experience—he or she may become more likely to dissociate or experience vivid dreams when falling asleep or waking up (van der Kloet, Giesbrecht, et al., 2012; van der Kloet, Merckelbach, et al., 2012). In turn, continued sleep deprivation leads to cognitive deficits, such as difficulties with memory and attention, which are aspects of symptoms of DID.

However, if the posttraumatic model is correct, there should be a significant number of cases of childhood DID. In fact, very few such cases have been documented (Giesbrecht et al., 2008, 2010; Boysen, 2011), and most studies of abused children have found only a great ability to dissociate, not the presence of alters (Piper & Merskey, 2004a). Moreover, most studies of adults with DID who experienced childhood abuse have not obtained independent corroborating evidence of abuse or trauma but rather rely solely on the patient’s—or an alter’s—report of abuse during childhood (Piper & Merskey, 2004a, 2004b).

237

The Sociocognitive Model In contrast to the posttraumatic model of DID, the sociocognitive model proposes that social interactions between therapist and patient (social factor) foster DID by influencing the beliefs and expectations of the patient (psychological factor). According to the sociocognitive model, the therapist unintentionally causes the patient to act in ways that are consistent with the symptoms of DID (Lilienfeld et al., 1999; Lynn et al., 2012; Sarbin, 1995; Spanos, 1994). This explanation is plausible in part because hypnosis was commonly used to bring forth alters, and researchers have pointed out that suggestible patients can unconsciously develop alters (and ensuing neurological changes) in response to the therapist’s promptings (Spanos, 1994). For instance, a therapist may encourage a patient to develop alters by asking leading questions (“Have people come up to you who seem to know you, but they are strangers to you?”) and then showing special interest when the patient answers “yes” to any such question. One finding that supports the sociocognitive model is that many people who have been diagnosed with DID had no notion of the existence of any alters before they entered therapy (Lilienfeld et al., 1999). In fact, in reviewing published studies on DID, no documented cases of DID occurring outside of therapy could be found (Boysen & VanBergen, 2013). In addition, cultural cues regarding DID (such as in portrayals in movies and memoirs or interviews of people with the disorder) may influence a patient’s behavior.

The Debate About Dissociative Identity Disorder

The phenomenon of people presenting in treatment with different personality states exists. The issue debated is how it arises and continues in a given patient. Proponents of the sociocognitive model recognize that childhood trauma—at least in some cases—can indirectly be associated with DID: Childhood trauma may lead people to become more suggestible or more able to fantasize, which can magnify the effects on their behavior of social interactions with a therapist (Lilienfeld et al., 1999; Lynn et al., 2012). In other words, dissociation and DID symptoms may be indirect results of childhood trauma rather than direct posttraumatic results.

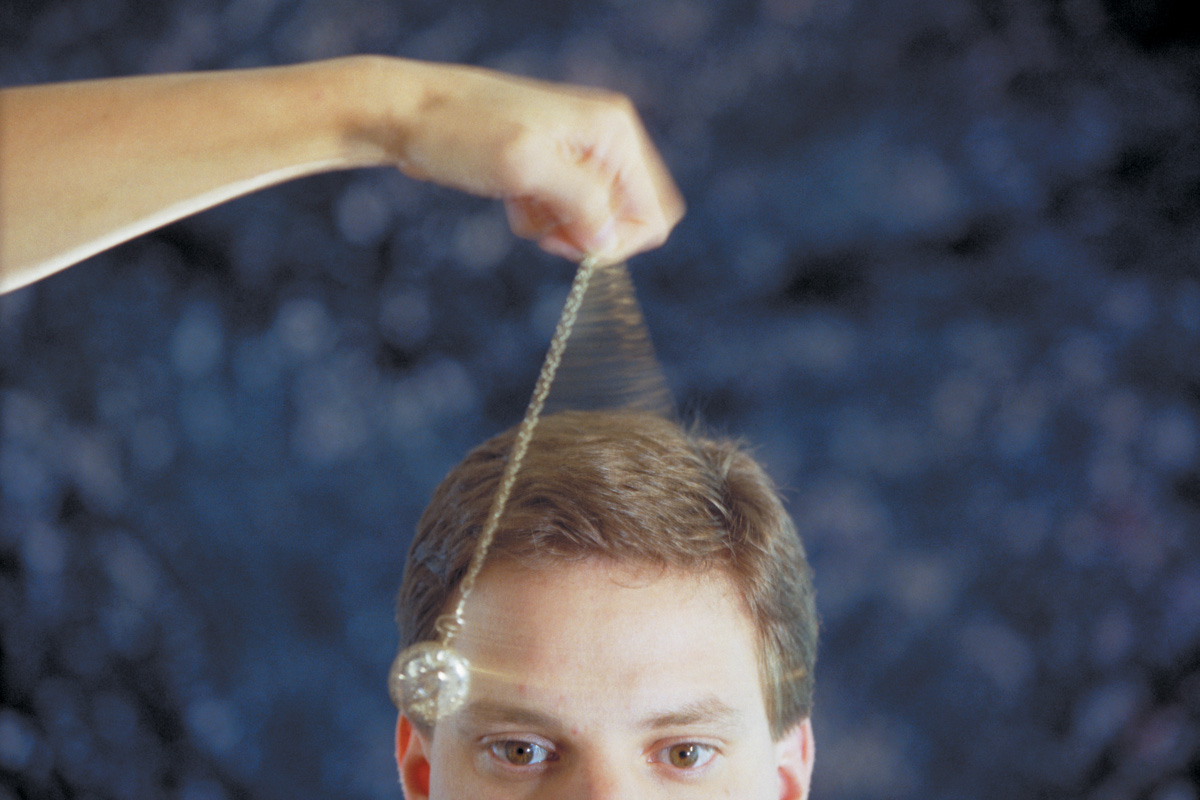

GETTING THE PICTURE

© BSIP SA/Alamy

238

Proponents of the sociocognitive model also point out that cultural influences, such as the airing of the movie Sybil, may have led therapists to ask leading questions regarding DID—and may have led highly suggestible patients to follow these leads unconsciously; such influences would account for the great variability in the number of cases over time. Proponents of the posttraumatic model counter that the increased prevalence of DID after 1976 simply reflects improved procedures for assessment and diagnosis.

In sum, we do know that severe trauma can lead to dissociative disorders and can have other adverse effects (Putnam, 1989; Putnam et al., 1995). However, we do not know whether all of the people who are diagnosed with DID have actually experienced traumatic events, nor even how severe an event must be in order to be considered “traumatic.” Similarly, experiencing a traumatic event does not specifically cause DID (Kihlstrom, 2005); some people respond by developing depression or an anxiety disorder. Further, as noted in Chapter 7, many people who experience a traumatic event do not develop any psychological disorder.

Treating Dissociative Disorders

In general, dissociative amnesia improves spontaneously, without treatment. However, clinicians who encounter people with other dissociative disorders have used some of the treatments discussed below. Because dissociative disorders are so rare, few systematic studies of treatments have been conducted—and none have attempted to determine which treatments are most effective for a particular dissociative disorder. Thus, we consider treatments for dissociative disorders in general.

Targeting Neurological Factors: Medication

In general, medication is not used to treat the symptoms of dissociative disorders because research suggests that it is not helpful for dissociative symptoms (Sierra et al., 2003; Simeon et al., 1998). However, people with dissociative disorders may receive medication for a comorbid disorder or for anxiety or mood symptoms that arise in response to the dissociative symptoms.

Targeting Psychological and Social Factors: Coping and Integration

Treatments that target the psychological factors underlying dissociative disorders focus on three elements: (1) reinterpreting the symptoms so that they don’t create stress or lead the patient to avoid certain situations; (2) learning additional coping strategies to manage stress (Hunter et al., 2005); and (3) for DID patients, addressing the presence of alters and dissociated aspects of their memories or identities. The first two foci are similar to aspects of treatment for PTSD (Kluft, 1999; see Chapter 7).

When addressing the presence of alters in patients with DID, the type of treatment a clinician employs depends on which theory he or she accepts and thus uses to guide treatment. Proponents of the posttraumatic model advise clinicians to identify in detail (or to “map”) each alter’s personality, recover memories of possible abuse, and then help the patient to integrate the different alters (Chu & International Society for the Study of Dissociation, 2005). In contrast, proponents of the sociocognitive model advise against mapping alters or trying to recover possible memories of abuse (Gee et al., 2003). Instead, they recommend that the therapist use learning principles to extinguish patients’ mention of alters: Alters are to be ignored, and the therapist doesn’t discuss multiple identities. Alters are interpreted as creations inspired by the patient’s desire for attention, and treatment focuses on current problems rather than on past traumas (Fahy et al., 1989; McHugh, 1993).

239

In addition, hypnosis has sometimes been used as part of treatment, particularly by therapists who treat DID according to the posttraumatic model; in this case, hypnosis might be used to help the patient learn about his or her different alters and integrate them into a single, functional whole (Boyd, 1997; Kluft, 1999). Using hypnosis is, by its very nature, a social event: The therapist helps the patient achieve a hypnotic state through suggestions and bears witness to whatever the patient shares about the dissociated experience. However, using hypnosis to treat DID is controversial because the patient will be more suggestible when in a hypnotic trance, and the therapist may inadvertently make statements that the patient interprets as suggestions to produce more DID symptoms.

Treatment may also focus on reducing the traumatic stress that can induce dissociative disorders. For instance, soldiers who experience dissociation during combat may be removed from the battlefield, which can then reduce the dissociation.

Feedback Loops in Treating Dissociative Disorders

ONLINE

When Breuer was treating Anna O., he relied on the “talking cure”—having her talk about relevant material, at first while in a hypnotic trance and later while not in a trance. This use of hypnosis continues today and is often part of a treatment program for people with dissociative disorders (Butler et al., 1996), including dissociative amnesia and DID (Putnam & Loewenstein, 1993). Here we examine hypnotic treatment for DID as it has been used from the perspective of the posttraumatic model, and we see how it leads to feedback loops among neurological, psychological, and social factors.

Researchers have investigated the neurological changes that occur as a result of hypnosis and established that hypnosis alters brain events (Crawford et al., 1993; Kosslyn et al., 2000; Spiegel et al., 1985). The specific brain changes vary, however, depending on the task being performed during the hypnotic trance. When hypnotized, patients may be able to retrieve information that was previously dissociated; in turn, this may allow them to experience perceptions and memories in a more normal way (psychological factor).

In addition, hypnosis can be induced only when patients are willing to be hypnotized, and the beneficial effects of hypnosis occur when patients go along with the therapist’s hypnotic suggestions (social factor). In turn, the hypnotic state brings about changes in brain activity (neurological factor), which ultimately might play a role in integrating the stored information that was previously dissociated.

Thinking Like A Clinician

The leading story of the evening news was that a 17-year-old young man murdered his stepfather. The boy said that his stepfather brutally abused him as a child, and local medical and emergency room records indicate numerous “accidents” that were consistent with such abuse. The young man also said that he has no memory of killing his stepfather; his defense attorney and several psychiatrists claim that he has DID and that an alter killed the stepfather. Based on what you have read in this chapter, how might this young man have developed this disorder? (Mention neurological, psychological, and social factors and possible feedback loops.) What would be appropriate treatments for him, and why? Do think it is fair to punish a patient with DID for what an alter did? Why or why not?

240