9.1 Substance Use: When Use Becomes a Disorder

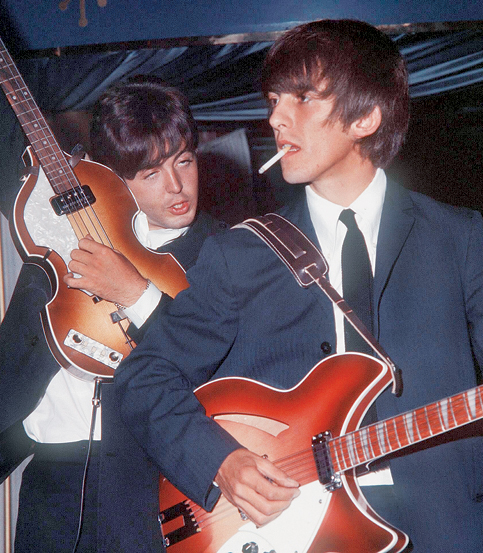

The Beatles used some drugs because that was what their peers did. For instance, almost all boys—and some girls—their age in Liverpool, England, smoked cigarettes. It was simply what was done. Similarly, the young band members drank alcohol; again, doing so was the norm. Sometimes they used a drug specifically for the effect it brought, such as when they took “uppers” (stimulants) to stay awake when performing late at night. When they toured in the early 1960s, they took drugs to relieve the monotony of life on the road; they would swallow a pill, “just to see what would happen” (Norman, 1997. A few years later, they took “acid” (LSD) to help them understand the meaning of life and attain enlightenment and peace. All four members of the Beatles tried various psychoactive substances. Psychoactive substances, commonly called drugs, are chemicals that alter mental ability, mood, or behavior. Frequent use of a psychoactive substance can develop into a substance use disorder.

258

Psychoactive substance A chemical that alters mental ability, mood, or behavior.

According to DSM-5, substance use disorders are characterized by a loss of control over urges to use a psychoactive substance, even though such use may impair functioning or cause distress. With substance use disorders, the psychoactive substance is taken repeatedly either because of its effect on mood, behavior, or cognition or because it prevents uncomfortable symptoms if the person stops taking the drug (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). The DSM-5 set of substance use disorders includes specific disorders for each substance. We first discuss substance use disorders in general and then focus on specific substances.

Substance use disorders Psychological disorders that are characterized by loss of control over urges to use a psychoactive substance, even though such use may impair functioning or cause distress.

Substance Use Versus Intoxication

Substance intoxication The reversible dysfunctional effects on thoughts, feelings, and behavior that arise from the use of a psychoactive substance.

The Beatles, individually and collectively, experimented with numerous drugs. Paul McCartney is generally described as having been the most cautious about drugs, whereas John Lennon used them regularly, sometimes continually. At one time or another, each Beatle could have been diagnosed with substance intoxication: reversible dysfunctional effects on thoughts, feelings, and behavior that arise from the use of a psychoactive substance (see TABLE 9.1). The specific effects of substance intoxication depend on the substance and whether a person uses it only occasionally (e.g., getting drunk on Saturday night) or chronically (e.g., drinking to excess every night).

|

| Reprinted with permission from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, (Copyright ©2013). American Psychiatric Association. All Rights Reserved. |

In contrast to substance intoxication, substance use is a general term that indicates simply that a person has used a substance—via smoking, swallowing, snorting, injecting, or otherwise absorbing it. This term does not indicate the extent or effect of the exposure to the substance.

Substance Use Disorders

Tolerance The biological response that arises from repeated use of a substance such that more of it is required to obtain the same effect.

Withdrawal The set of symptoms that arises when a regular substance user decreases or stops intake of an abused substance.

The Beatles used stimulants nightly when performing in Germany, but does that mean they were abusing the drugs or had a substance use disorder? Were they addicted? Some mental health clinicians and researchers have avoided using the term addiction, partly because of its negative moral connotations. However, other clinicians and researchers are in favor of using the term addiction (O’Brien et al., 2006). Those clinicians and researchers define addiction as the compulsion to seek and then use a psychoactive substance either for its pleasurable effects or, with continued use, for relief from negative emotions such as anxiety or sadness. These compulsive behaviors persist, despite negative consequences (American Society of Addiction Medicine, 2011).

Like this definition of addiction, the DSM-5 definition of substance use disorders focuses on the behaviors related to obtaining and using a drug, as well as the consequences of that use. Whereas intoxication refers to the direct results of using a substance, the criteria of a substance use disorder focus both on the indirect effects of repeated use, such as unmet obligations or risky behavior while using the substance (for instance, driving while under the influence), and the cravings and biological changes that can occur with repeated use or stopping use. DSM-5 defines craving as a strong desire or urge to use the substance. TABLE 9.2 lists the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria.

|

A problematic pattern of use of an intoxicating substance leading to clinically significant impairment or distress, as manifested by at least two of the following, occurring within a 12-month period:

|

| Reprinted with permission from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, (Copyright ©2013). American Psychiatric Association. All Rights Reserved. |

259

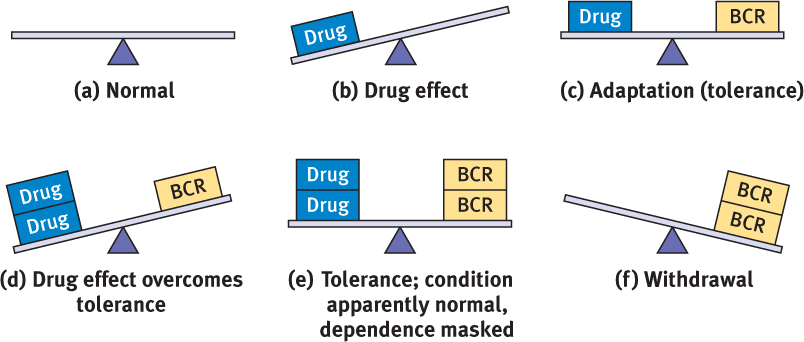

Two neurologically based symptoms of substance use disorders can contribute to the diagnosis: tolerance and withdrawal (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Tolerance occurs when, with repeated use, more of the substance is required to obtain the same effect. For instance, someone who drinks alcohol regularly is likely to develop tolerance to alcohol and find that it takes more drinks to obtain a “buzz” and even more drinks to get drunk. With regular use of alcohol and some drugs, the body adapts and tries to compensate for the repeated influx of the substance (see Figure 9.1). People who have been given certain medications for medical problems, such as some pain relievers, may develop tolerance even when taking the medications as prescribed; in such cases, tolerance would not be considered a symptom of a substance use disorder.

Withdrawal refers to the set of symptoms that arises when a regular substance user decreases intake of the substance. As shown in Figure 9.1, withdrawal arises because the body has compensated for the repeated influx of a drug, and the neurological compensatory mechanisms are still in place when the person stops taking the drug, but the drug is no longer there to compensate for them. Withdrawal symptoms can make it difficult for habitual users of some substances to cut back or stop their use: As they cut back, they may experience uncomfortable or even life-threatening symptoms that are temporarily alleviated by resuming use of the substance. In most cases, substances that can lead to tolerance with regular use are also likely to produce withdrawal symptoms if stopped or taken at lower doses. As with tolerance, people taking certain medications for a medical problem may experience withdrawal symptoms if the medication is stopped or the dosage lowered. In such cases, withdrawal would not be considered a symptom of a substance use disorder.

260

Substance Use Disorder as a Category or on a Continuum?

GETTING THE PICTURE

Punchstock/BananaStock

© Chuck Savage/Corbis

According to DSM-5, a habitual drug user either is or is not diagnosed with a substance use disorder; this is a categorical decision. However, research suggests that a more meaningful way to conceptualize harmful substance use, at least of alcohol, is on a continuum of severity (Heath et al., 2003; Langenbucher et al., 2004; Sher et al., 2005). According to this view, a substance use disorder anchors one end of a continuum, and unproblematic substance use anchors the other end. This continuum can be defined by the frequency, quantity, and duration of use, as well as the effects of use on daily functioning. The more frequent the use, the larger the quantity, or the longer the use has been going on, the more likely the use is to become a substance use disorder.

According to the continuum approach, we would determine whether any of the Beatles had a stimulant use disorder based on how much, how often, and for how long each of them took the stimulant, and the extent to which such use impaired their daily functioning.

261

Use Becomes a Problem

People can develop substance use disorders in three general ways. First, substance use disorders can arise unintentionally, as can occur through environmental exposure. Second, substance use disorders can develop when the psychoactive element is a side effect, and the substance is taken for medicinal reasons unrelated to the psychoactive effect. Third, substance use disorders can develop as a result of the intentional use of a substance for its psychoactive effect. In this third path toward substance use disorders, someone may know the risks of using the substance but nonetheless underestimate his or her own level of risk (Weinstein, 1984, 1993). It is this third path toward developing substance use disorders that has been the target of most research, and two main models have been proposed to explain this type of slide from use to disorder.

Common Liabilities Model

Common liabilities model The model that explains how neurological, psychological, and social factors make a person vulnerable to a variety of problematic behaviors, including substance use disorders; also called problem behavior theory.

The common liabilities model (also called problem behavior theory; Donovan & Jessor, 1985) explains how neurological, psychological, and social factors make a person vulnerable to developing a variety of problematic behaviors. It was developed in response to the results from a study that followed students from grades 7–9 into adulthood; the researchers found that adolescents who exhibited “problem behaviors,” such as drug and alcohol use, early sexual intercourse, and delinquent behaviors (e.g., stealing and gambling), were likely later in life to develop a substance use disorder. The researchers proposed that these various problem behaviors at different ages may stem from the same underlying factors, called common liabilities. Subsequent studies have supported this explanation (Agrawal et al., 2004; Ellickson et al., 2004; Windle & Windle, 2012). One particularly important common liability is a problem with impulsivity—especially with difficulty restraining urges to engage in potentially harmful behaviors—which also underlies a variety of other disorders that involve compulsive behaviors, such as gambling.

Gateway Hypothesis

Gateway hypothesis The proposal that use can become a use disorder when “entry” drugs serve as a gateway to (or the first stage in a progression to) use of “harder” drugs.

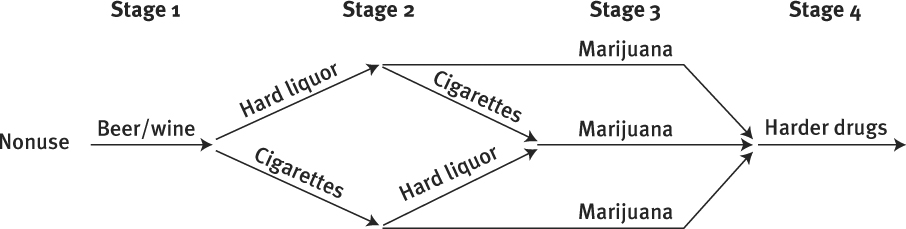

Another model that researchers have used to a explain the progression from use to a substance use disorder is the gateway hypothesis and the related stage theory (Kandel, 2002; Kandel & Logan, 1984). According to the gateway hypothesis, “entry” drugs such as cigarettes and alcohol serve as a gateway to (or the first stage in a progression to) use of “harder” drugs, such as cocaine, or illegal use of prescription medication. Researchers have found that some, but not all, adolescent users of entry drugs did go on to use marijuana (White et al., 2007), and some of these marijuana users moved on to harder drugs and hard liquor (Kandel, 2002; Kandel & Logan, 1984). Teens are unlikely to experiment with marijuana unless they first experimented with legal—but restricted—substances such as alcohol. Similarly, adolescents and young adults don’t generally try other illegal substances without having used marijuana (see Figure 9.2).

This general pattern of progression has been found in various countries and among different ethnic groups (Kandel & Yamaguchi, 1985). Moreover, people who develop a substance use disorder often passed through a particular progression of stages of drug use: initiation, experimentation, casual use, regular use, and then substance use disorder (Clayton, 1992; Werch & Anzalone, 1995). Of course, not everybody progresses to the end of this sequence. In fact, the gateway hypothesis is not a blueprint for all users; rather, it is a way to understand how people who use substances can end up having a substance use disorder.

262

Comorbidity

As we’ve noted in earlier chapters, many people with psychological disorders abuse substances—that is, they develop one or more symptoms of a substance use disorder—particularly alcohol, marijuana, cocaine, and opiates (Lingford-Hughes & Nutt, 2000). Studies have found that almost half of people with alcohol use disorder (the name for the substance use disorder when the substance is alcohol) also had another psychological disorder—and almost three-quarters of those with a different type of substance use disorder had another psychological disorder (Conway et al., 2006; Regier et al., 1993). Common comorbid disorders include mood disorders (most frequently depression), posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), schizophrenia, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD, discussed in Chapter 13), a disorder marked by problems sustaining attention or by physical hyperactivity (Brady & Sinha, 2005). People who have a non-substance-related psychological disorder have a greater risk of substance use turning into a use disorder (Lev-Ran et al., 2013). When substance use disorder develops after another psychological disorder has developed, clinicians may infer that the person is using substances in an attempt to alleviate symptoms of the other disorder—to self-medicate.

Polysubstance Abuse

Polysubstance abuse A behavior pattern of abusing more than one substance.

As was true of the Beatles, some people abuse more than one substance, a behavior pattern that is called polysubstance abuse. One study found that among alcoholics, 64% also had an additional type of substance use disorder (Staines et al., 2001). Polysubstance abuse is dangerous because of the ways that drugs can interact: One lethal combination occurs when someone takes a drug that slows down breathing, such as barbiturates (which are often used as sleeping pills), along with alcohol. A form of polysubstance abuse that is seldom recognized is the combination of alcohol and cigarettes (nicotine): Cigarettes are the biggest killer of all drugs, and this is particularly true among alcoholics. Most alcoholics are more likely to die from nicotine-related medical consequences, such as cardiovascular disease, than from alcohol-related ones (Hurt et al., 1996).

Prevalence and Costs

The various types of substance use disorders are among the most common psychological disorders. In 2009, an estimated 9% of Americans aged 12 and older, or 22.5 million people, had a substance use disorder (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration [SAMHSA], 2010). Generally, men are more likely than women to be diagnosed with a substance use disorder, although women are more likely to be diagnosed with a substance use disorder related to legally obtained prescription medications (Simoni-Wastila et al., 2004).

The prevalence of drug use and substance use disorders varies across ethnic and racial groups in the United States. However, significant variations occur within each broad ethnic or racial category. For example, among Americans of Hispanic descent, the 1-month prevalence rate of heavy drinking (five or more drinks in a sitting) for Cuban Americans is 1.7%, whereas it is 7.4% for Mexican Americans (NIDA, 2003). Therefore, prevalence rates of racial and ethnic groups provide only a general overview, and they do so only at a particular moment in time.

A substance use disorder affects not only the user but also family members and friends, coworkers, and colleagues. Substance use disorders are associated with violence toward family members and neglect of children (Easton et al., 2000; Stuart et al., 2003). Parents who abuse substances may feel guilty and ashamed about their substance abuse, which ironically may lead them to increase their substance use to cope with these feelings (Gruber & Taylor, 2006). Children may find themselves shouldering adult tasks and responsibilities (Haber, 2000). Children of parents who abuse substances are at increased risk of developing emotional and behavioral problems (Grant, 2000; Kelley & Fals-Stewart, 2002).

263

Culture and Context

The line between use and abuse shifts over time and across cultures and ethnic groups. For example, cocaine was used legally as a remedy for many ills in the second half of the 19th century, but it has now been illegal for decades. And, during the Prohibition era (1920–1933) in the United States, alcohol use was illegal.

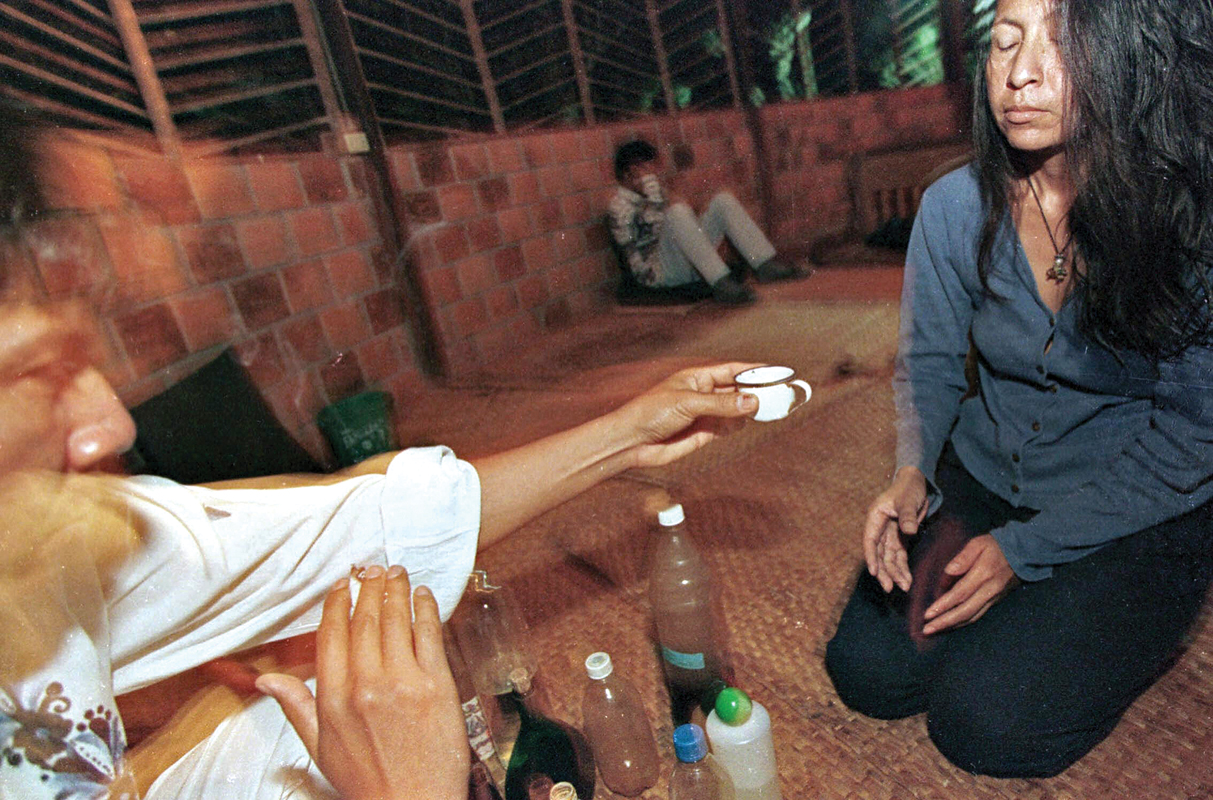

Various cultures use psychoactive substances for different purposes. Some Native American tribes, for example, use peyote or psilocybin mushrooms (which, when eaten, produce vivid hallucinations) as part of sacred rituals. Such cultural use of psychoactive substances is strongly regulated, and there are penalties for abusing those substances, including being put to death (Trimble, 1994).

In the remaining sections of this chapter we discuss specific substances that can develop into use disorders. We first describe what they are and consider the ways in which they have their effects. Because treatments for various types of substance use disorders are similar, we consider treatment for all types of substance use disorders in the final section of the chapter.

Thinking Like A Clinician

Jorge and his friend Rick worked hard and played hard in high school. On weekend evenings, usually their only free time, they’d binge drink, along with others in their group. They went to different colleges. Jorge kept up his “study hard, party hard” lifestyle; Rick didn’t do much binge drinking in college, but he started smoking marijuana in the evenings when he was done studying and he’d go dancing on Saturday nights and sometimes take stimulants. What information would you want to know in order to determine whether Jorge or Rick had a substance use disorder?