10.4 Understanding Eating Disorders

In the sections that follow, we focus on the two eating disorders that are best understood and for which treatments have been researched most extensively: anorexia and bulimia. Moreover, given that up to half of the people who have anorexia or bulimia have had or will have another of these disorders, it makes sense to examine the etiology of these disorders collectively rather than individually.

Why do these eating disorders arise? Marya Hornbacher asked this question and ventured the following response:

While depression may play a role in eating disorders, either as cause or effect, it cannot always be pinpointed directly, and therefore you never know quite what you’re dealing with. Are you trying to treat depression as a cause, as the thing that has screwed up your life and altered your behaviors, or as an effect? Or simply depressing? Will drug therapy help, or is that a Band-Aid cure? How big a role do your upbringing and family play? Does the culture have anything to do with it? Is your personality just problematic by nature, or is there, in fact, a faulty chemical pathway in your brain? If so, was it there before you started starving yourself, or did the starving put it there?…All of the above?

(1998, pp. 195–196)

309

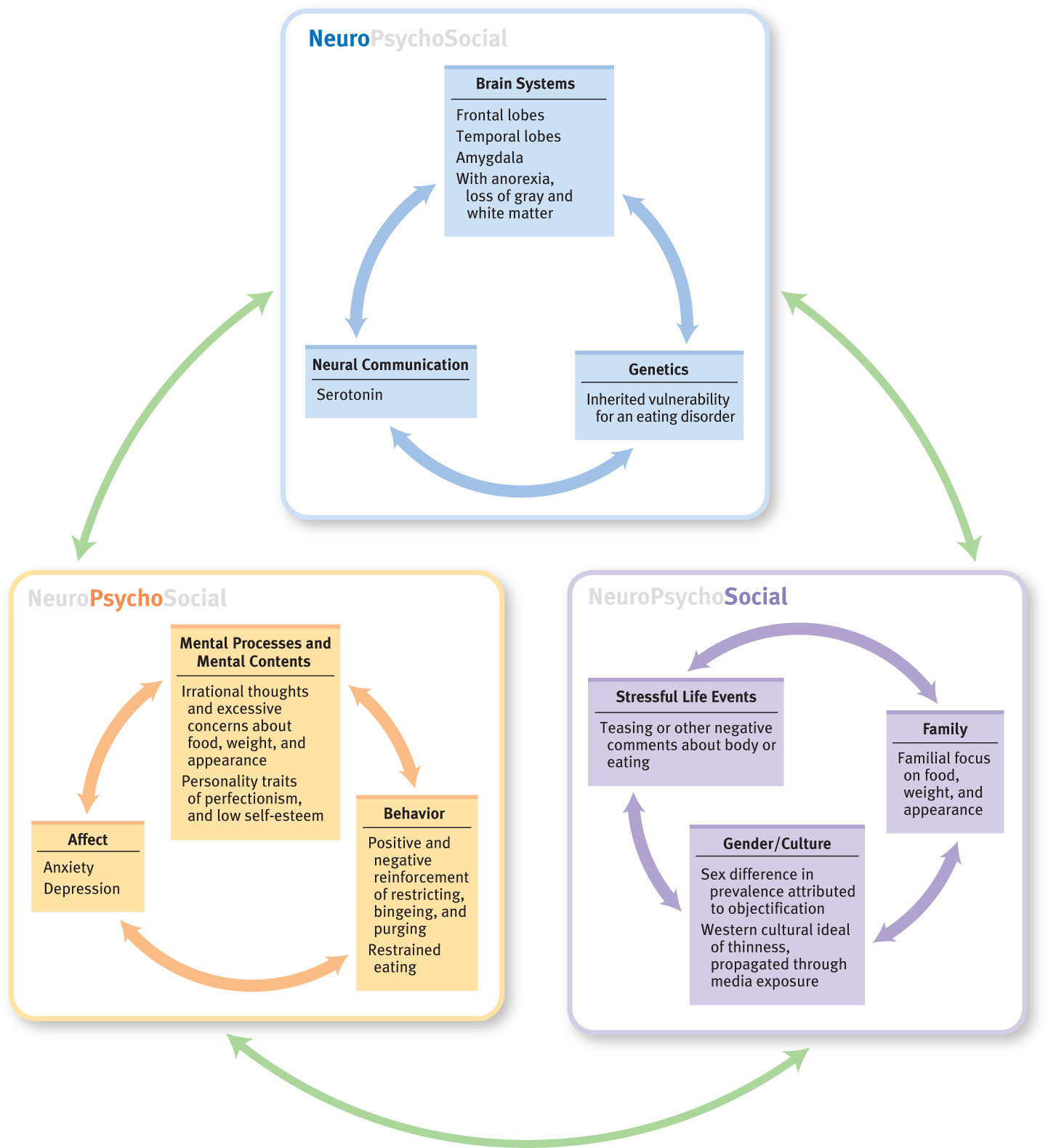

In this passage, Hornbacher is trying to understand how, or why, some people—but not others—develop an eating disorder. Note that she mentions explanations that involve all three of the types of factors in the neuropsychosocial approach, although she does not consider ways in which such factors might interact.

Once an eating disorder has developed, it is difficult to disentangle the causes of the eating disorder from the widespread effects of an eating disorder on neurological (and, more generally, biological), psychological, and social functioning. This difficulty in untangling cause and effect means that researchers do not know which of the neuropsychosocial factors that are associated with eating disorders actually produce the disorders. All that can be said at this time is that a number of factors are associated with the emergence and maintenance of eating disorders (Dolan-Sewall & Insel, 2005; Jacobi et al., 2004; Striegel-Moore & Cachelin, 2001).

An additional challenge to researchers is the high rate of comorbidity of other psychological and medical disorders with eating disorders, which makes it difficult to determine the degree to which risk factors uniquely lead to eating disorders rather than being associated more generally with the comorbid disorders (Jacobi et al., 2004).

Neurological Factors: Setting the Stage

We’ve already noted that the excessive caloric restriction in anorexia leads to specific medical effects, notably changes in metabolism, and body functioning. The eating changes and purging involved in bulimia (and anorexia, if purging occurs) bring their own medical effects and biological changes.

Brain Systems

Neuroimaging studies have revealed many differences between the brains of people with eating disorders and those of control participants (Frank et al., 2004; Kaye, Frank et al., 2005). Most notably, people who have anorexia have unusually low activity in two key areas of the brain: (1) the frontal lobes, which are involved in inhibiting responses and in regulating behavior more generally (a deficit in such processing may contribute to eating too much or eating too little), and (2) the portions of the temporal lobes that include the amygdala, which is involved in fear and other strong emotions (fear helps prevent people from putting themselves in danger, and dampening this emotion may contribute to eating disorders).

Neuroimaging studies not only have documented abnormalities in the functioning of different parts of the brain in people who have eating disorders but also have shown that the structure of the brain itself changes with these disorders. In fact, anorexia is associated with loss of both gray matter (cell bodies of neurons) and white matter (myelinated axons of the neurons) in the brain (Addolorato et al., 1997; Frank et al., 2004; Herholz, 1996). The gray matter carries out various sorts of cognitive and emotion-related processes, such as those involved in learning and in fear responses. Deficits in white matter may imply that different parts of the brain are not communicating appropriately, which could contribute to the problems patients with anorexia have when they try to convert an intellectual understanding of their disorder into changes in their behavior. Many of these structural deficits improve when the patient recovers, although they do not necessary disappear completely (Frank et al., 2004; Herholz, 1996). Thus, an eating disorder may have long-term consequences for a person’s neural functioning, which in turn affects cognitive abilities and emotional responses.

310

Neural Communication: Serotonin

Losing large amounts of weight (as occurs in anorexia) and the associated malnutrition clearly change the amounts of serotonin and other neurotransmitters. We will focus here on serotonin because it is involved in regulating a wide variety of behaviors and characteristics that are associated with eating disorders, including binge eating and irritability (Hollander & Rosen, 2000; McElroy et al., 2000).

Neuroimaging research has shown that serotonin receptors function abnormally in patients with anorexia and bulimia (Kaye, Bailer et al., 2005; Kaye, Frank et al., 2005). However, evidence seems to imply that the serotonin receptors are abnormal before patients develop anorexia. As discussed in Chapters 5 and 6, serotonin is related to mood and anxiety. Prior to developing anorexia, patients tend to be anxious and obsessional, and these traits persist even after recovery, which suggests a biologically based anxious temperament; this temperament may be related to serotonin levels or functioning (Kaye et al., 2003).

Consistent with this view, researchers have found that people with anorexia (Kaye, Bailer et al., 2005) and bulimia (Kaye et al., 2000; Smith et al., 1999) are less responsive to serotonin than normal. In fact, the worse the symptoms of bulimia, the less responsive to serotonin the patient generally is (Jimerson et al., 1992).

Genetics

When Marya Hornbacher told her parents that she had been making herself throw up, her mother admitted, “I used to do that.” Did Hornbacher’s genes predispose her to developing bulimia? As is true for people with mood disorders and anxiety disorders, people with an eating disorder are more likely than average to have family members with an eating disorder—but not necessarily the same disorder that they themselves have (Lilenfeld & Kaye, 1998; Strober et al., 2000).

Like genetic studies of other types of disorders, such studies of eating disorders compare identical twins to fraternal twins. The research findings indicate that anorexia has a substantial heritability, but estimates range from as low as 33% to as high as 88% (Bulik, 2005; Jacobi et al., 2004). Twin studies of bulimia also indicate that the disorder is influenced by genes and also yield a wide range of estimates of heritability, from 28% to 83% (Bulik 2005; Jacobi et al., 2004). Given that many people with bulimia previously had anorexia, it isn’t surprising that both disorders have the same wide range of heritabilities; there is significant overlap in the two populations. The large variation in heritabilities may simply indicate, once again, that genes aren’t destiny; the way the environment interacts with the genes is also important.

Psychological Factors: Thoughts of and Feelings About Food

Eating and breathing are both essential to life, but eating can also evoke powerful feelings, memories, and thoughts. Hornbacher recalls her associations to eating:

My memories of childhood are almost all related to food…. I was my father’s darling, and the way he showed love was through food. I would give away my lunch at school, then hop in my father’s car, and we’d drive to a fast-food place and, essentially, binge.

311

My mother was another story altogether. She ate, some. She would pick at cottage cheese, nibble at cucumbers, scarf down See’s Candies. But she, like my father, and like me, associated food with love, and love with need.

(1998, p. 27)

Many psychological risk factors are not uniquely associated with eating disorders. Factors such as negative self-evaluation, sexual abuse and other adverse experiences, the presence of comorbid disorders (e.g., depression and anxiety disorders; Jacobi et al., 2004), and using avoidant strategies to cope with problems (Pallister & Waller, 2008; Spoor et al., 2007) are also associated with psychological disorders more generally. Thus, many researchers have focused on factors that are specifically related to symptoms of eating disorders—factors associated with food, weight, appearance, and eating. In the following sections we examine research findings about these factors.

Thinking About Weight, Appearance, and Food

People with eating disorders have automatic, irrational, and illogical thoughts about weight, appearance, and food (Garfinkel et al., 1992; Striegel-Moore, 1993). We consider two kinds of such thoughts in the following sections.

Excessive Concern With Weight and Appearance

Some people with eating disorders have excessive concern with—and tend to over-value—their weight, body shape, and eating (Fairburn, 1997; Fairburn & Cooper, 2011). For instance, they may weigh themselves multiple times a day and feel bad about themselves when the scale indicates that they’ve gained half a pound. Some people are so concerned with weight and appearance that their food intake, weight, and body shape come to define their self-worth.

The two characteristics that are the most consistent predictors of the onset of an eating disorder are dieting and being dissatisfied with one’s body (Neumark-Sztainer et al., 2011; Thompson & Smolak, 2001). Such concerns help maintain bulimia because people with these characteristics believe that their compensatory behaviors reduce their overall caloric intake (Fairburn et al., 2003).

Abstinence Violation Effect

Abstinence violation effect The result of violating a self-imposed rule about food restriction, which leads to feeling out of control with food, which then leads to overeating.

Many people who have an eating disorder engage in automatic, illogical, black-or-white thinking about food: Vegetables are “good,” whereas desserts are “bad.” They may come to view themselves in the same way: They are “good” when acting to lose weight and “bad” when eating a “bad” food or when they feel that their eating is out of control. The abstinence violation effect (Polivy & Herman, 1993) occurs when the violation of a self-imposed rule about food restriction leads to feeling out of control with food, which then leads to overeating. For instance, having taken a taste of a friend’s ice cream, a person thinks, “I shouldn’t have had any ice cream; I’ve blown it for the day, so I might was well have my own ice cream—in fact, I’ll get a pint and eat the whole thing.” Then, after she eats the ice cream, she tries to negate the calories ingested during the binge by purging or using some other compensatory behavior. Thus, the abstinence violation effect explains bingeing that occurs after the person has “transgressed.”

Operant Conditioning: Reinforcing Disordered Eating

As with many disorders, operant conditioning plays a role in the development and maintenance of symptoms—in this case, as we explain below, symptoms of disordered eating.

312

First, the symptoms of most eating disorders—anorexia, bulimia, or binge eating disorder—may inadvertently be reinforced through operant conditioning. For instance, preoccupations with food and weight or bingeing and purging can provide distractions from work pressures, family conflicts, or social problems. The never-ending preoccupations with food, weight, and body are negatively reinforced because they provide relief from what the person might otherwise be preoccupied about. (Remember that negative reinforcement is still reinforcement, but it occurs when something aversive is removed, which is not the same as punishment.)

Second, operant conditioning occurs when restricting behaviors are positively reinforced by the person’s sense of power and mastery over her appetite, although such feelings of mastery are often short-lived as the disease takes over (Garner, 1997). Hornbacher noted: “The anorexic body seems to say: I do not need. It says: Power over the self” (1998.

A third way in which operant conditioning affects eating disorders occurs when people are positively reinforced for “losing control” of their appetite and bingeing. How can losing control be positively reinforcing? Easy: They’ve set up the rules so that they get to eat certain foods they enjoy (positive reinforcement) only when they let themselves lose control of their food intake. That is, during a binge, people eat foods that they normally don’t eat at all or eat only in small quantities—typically fats, sweets, or carbohydrates. This means that the only way some people can eat foods they may enjoy—such as ice cream, cake, candy, or fried foods—is by being “out of control.”

Fourth, bingeing can also induce an endorphin rush, which creates a pleasant feeling much like a “runner’s high,” which is positively reinforcing. And, fifth, operant conditioning may occur because purging can be negatively reinforcing by relieving the anxiety and fullness that are created by overeating.

Personality Traits as Risk Factors

Particular personality traits are associated with—and are considered risk factors for—eating disorders: perfectionism and low self-esteem. Perfectionism is a persistent striving to attain perfection and excessive self-criticism about mistakes (Antony & Swinson, 1998; Franco-Paredes et al., 2005). Numerous studies find that people with eating disorders have higher levels of perfectionism than do people who do not have these disorders (Forbush et al., 2007). High perfectionism may lead to an intense drive to attain a desired weight or body shape and thus may contribute to the thoughts and behaviors that underlie an eating disorder. As illustrated in Figure 10.2, perfectionists are painfully aware of their imperfections, which is aversive for them. This heightened awareness of personal flaws—real or imagined—is called aversive self-awareness and leads to significant emotional distress, which may temporarily be dulled by focusing on immediate aspects of the environment, such as occurs with bingeing. Thus, bingeing may provide an escape from the emotional distress associated with perfectionism (Blackburn et al., 2006; Heatherton & Baumeister, 1991).

313

In addition, people who have low self-esteem may try to raise their self-esteem by controlling their food intake, weight, and shape, believing that such changes will increase their self-worth (Geller et al., 2000). For instance, they may think, “If I restrict my calories, that’ll prove that I’m in control of myself and worthy of respect.” However, efforts to increase self-worth in this way end up having a paradoxical effect: To the extent that the person fails to control food intake, weight, and shape, her self-esteem falls even lower—she feels that she’s failed, yet again, to achieve something she wanted.

Dieting, Restrained Eating, and Disinhibited Eating

Restrained eating Restricting intake of specific foods or overall number of calories.

Frequently restricting specific foods—such as “fattening” foods—or overall caloric intake (as occurs when dieting or trying to maintain one’s current weight) is referred to as restrained eating. If you’ve ever been on some type of diet, you know that continuing to adhere to such restrictions can be challenging. And at times the diet may feel so constraining that you get discouraged and frustrated and simply give up—which can lead to a bout of disinhibited eating, bingeing on a restricted type of food or simply eating more of a nonrestricted type of food (Polivy & Herman, 1985). In fact, dieters and people with eating disorders often alternate restrictive eating with disinhibited eating (Fairburn et al., 2005; Polivy & Herman, 1993, 2002).

Restrained eaters can become insensitive to internal cues of hunger and fullness. In order to maintain restricted eating, they may stop eating before they get a normal feeling of fullness and so end up trying to tune out sensations of hunger. If they binge, they may eat past the point of normal fullness. They therefore need to rely on external guides, such as portion size or elapsed time since their last meal, to control their food intake (Polivy & Herman, 1993). However, using external guides to direct food intake requires cognitive effort—to monitor the clock or to calculate how much food was last eaten and how much food should be eaten next. When a person is thinking about other tasks (such as a job or homework assignment), she may temporarily stop using external guides and simply eat, which in turn may lead to disinhibited or binge eating (Baumeister et al., 1998; Kahan et al., 2003).

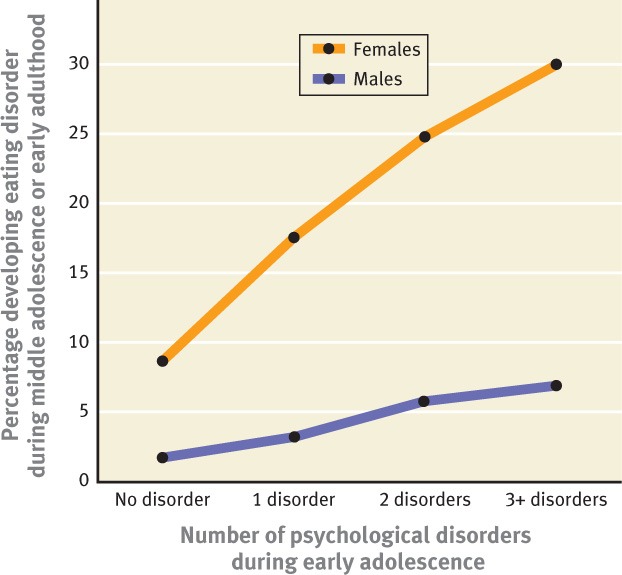

Other Psychological Disorders as Risk Factors

Another factor associated with the subsequent development of an eating disorder is the presence of a psychological disorder in early adolescence (see Figure 10.3), particularly depression. A longitudinal study of 726 adolescents found that having a depressive disorder during early adolescence was associated with an increased risk for later dietary restriction, purging, recurrent weight fluctuations, and the emergence of an eating disorder. This was the case even when researchers statistically controlled for other disorders or eating problems before adulthood (Johnson, Cohen, Kotler, et al., 2002).

Social Factors: The Body in Context

Various social factors contribute to eating disorders. One social factor is the influence of family and friends, and another social factor is culture, which can contribute to eating disorders by promoting an ideal body shape. In this section we discuss these social factors as well as explanations of why so many more females than males develop eating disorders.

314

The Role of Family and Peers

Researchers have had trouble disentangling the influences of genes on eating disorders from the influences of the family for two main reasons:

- Family members provide a model for eating, body image, and appearance concerns through their own behaviors (Stein, Wooley, Cooper, et al., 2006). For example, parents who spend a lot of time on their appearance before leaving the house model that behavior for their children.

- Family members affect a child’s concerns through their responses to the child’s body shape, weight, and food intake (Stein, Wooley, Senior, et al., 2006; Tantleff-Dunn et al., 2004; Thompson et al., 1999). For example, if a parent inquires daily about how much food his or her child ate at lunch (or weighs the child daily), the child learns to pay close attention to caloric intake and daily fluctuations in weight.

Children whose parents are overly concerned about these matters are more likely to develop an eating disorder (Strober, 1995). But this finding could also reflect shared genes.

Peers can shape a person’s relationship to eating, food, and body, especially if they tease or criticize a person concerning her weight, appearance, or food intake; such comments can have a lasting influence on her (dis)satisfaction with her body, her willingness to diet, and her self-esteem. Such influences can make a person more vulnerable to developing an eating disorder (Cash, 1995; Keery et al., 2005).

Unfortunately, many girls and women feel that symptoms of eating disorders—particularly preoccupations with food and weight—are “normal” and that talking about these topics is a way to bond with others. Hornbacher was aware of this social facet of eating disorders and its underlying drawback:

Women use their obsession with weight and food as a point of connection with one another, a commonality even between strangers. Instead of talking about why we use food and weight control as a means of handling emotional stress, we talk ad nauseum about the fact that we don’t like our bodies.

(1998, p. 283)

The Role of Culture

Some researchers believe that eating disorders have become more common and pervasive in recent decades. However, a meta-analysis of the incidence of eating disorders across cultures over the 20th century found only a small increase in the number of cases of anorexia. In contrast, the incidence of bulimia substantially increased from 1970 to 1990 (Keel & Klump, 2003)—which suggests a cultural influence—because bulimia arises only in the context of concerns about weight (Striegel-Moore & Cachelin, 2001).

Three elements come together to create the engine driving the culturally induced increase in eating disorders (Becker et al., 2002):

- a cultural ideal of thinness,

- repeated media exposure to this thinness ideal, and

- a person’s assimilation of the thinness ideal.

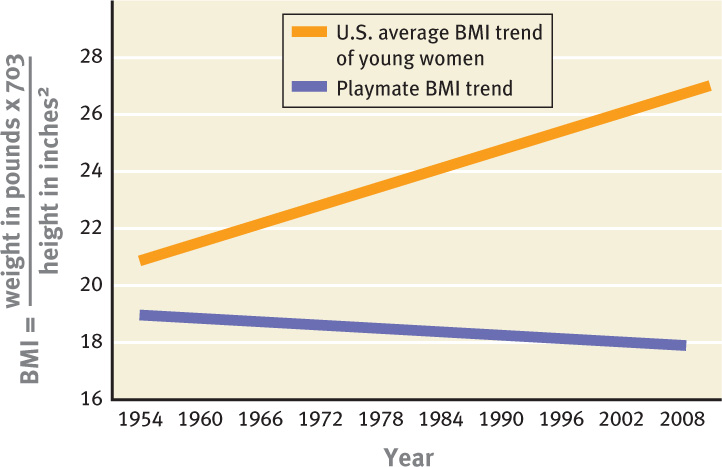

In order to examine the cultural ideal of thinness, David Garner and colleagues (1980) conducted an innovative study: They tracked the measurements of Miss America contestants and Playboy centerfold playmates over time and found that their waists and hips gradually became smaller. Other studies have found similar results (Andersen & DiDomenico, 1992; Field et al., 1999; Nemeroff et al., 1994). In fact, while the size of playmates’ bodies has decreased over time (as assessed by the body mass index, or BMI, an adjusted ratio of weight to height), the average BMI of women age 20–29 has increased (see Figure 10.4; Ogden et al., 2004, Gammon, 2009). During the same period studied by Garner and colleagues, the prevalence of eating disorders increased in the United States. It is not clear whether the contestants and playmates were creating or following a cultural trend in ideal body shape. What is clear is that society’s pressure to be thin increases women’s—and girls’—dissatisfaction with their bodies, which is a risk factor for eating disorders (Grabe & Hyde, 2006; Lynch et al., 2008).

315

The cultural influence on weight and appearance isn’t limited to women: Men who regularly engage in activities such as modeling and wrestling, which draw attention to their appearance and weight, are increasingly likely to develop eating disorders (Garner et al., 1998; Sundgot-Borgen, 1999). Similarly, men who have a heightened awareness of appearance (Ousley et al., 2008), such as some in the gay community, are also more likely to develop eating disorders (Russell & Keel, 2002).

Eating Disorders Across Cultures

Eating disorders occur throughout the world but are found mainly in industrialized Western or Westernized countries (Lee et al., 1992; Pike & Walsh, 1996). Immigration to a Western country and internalization of Western norms increase the risk of developing symptoms of an eating disorder, as occurs among people who immigrate from China and Egypt to Western countries (Lee & Lee, 1996; Perez et al., 2002). Westernization (or modernization) of a culture similarly increases dieting (Gunewardene et al., 2001), which is a risk factor for eating disorders. In addition, as girls and women move into a higher socioeconomic bracket, they are increasingly likely to develop an eating disorder (Polivy & Herman, 2002).

Within the United States, prevalence rates of eating disorders vary across ethnic groups, based on different ideals of beauty and femininity: Native Americans have a higher risk for eating disorders than do other ethnic groups (Crago et al., 1996), and Black Americans have had the lowest risk (Striegel-Moore et al., 2003). However, prevalence rates are increasing among Black and Latina women (Franko et al., 2007; Gentile et al., 2007; Shaw et al., 2004; Taylor et al., 2007), perhaps because of the growing number of ethnic models in mainstream ads who are as thin as their White counterparts (Brodey, 2005).

The Power of the Media

The power of the media to influence cultural ideals of beauty and femininity is illustrated by the results of an innovative study in Fiji (a group of islands in the South Pacific) by Anne Becker and colleagues (2002). Prior to 1995, there was no television in Fiji. Traditional Fijian culture promoted robust body shapes and appetites, and there were no cultural pressures for thinness or dieting. Researchers collected data from adolescent girls shortly after the introduction of television in 1995 and again 3 years later. At the beginning of the study, when a large body size was the cultural ideal, they found almost no one who felt they were “too big or fat.” After 3 years of watching television (primarily shows from Western countries), however, 75% reported that they felt “too big or fat” at least some of the time. In addition, feeling too big was associated with dieting to lose weight, which had become very prevalent: 62% of the girls had dieted within the prior 4 weeks.

A similar process might be occurring in industrialized societies, where ideals of thinness saturate the environment through television, movies, magazines, advertisements, books, and even cartoons. Numerous studies have documented associations between media exposure and disordered eating (Bissell & Zhou, 2004; Kim & Lennon, 2007); for instance, the more time adolescent girls spent watching television, the more likely they were to report disordered eating a year later (Harrison & Hefner, 2006). However, not all girls and women who view these media images end up with an eating disorder. Some people are more affected than others, perhaps because of a combination of neurological, psychological, and social risk factors. For them, chronic exposure to these types of images may tip the scales and set them on a course toward an eating disorder (Ferguson et al., 2011; Levine & Harrison, 2004).

316

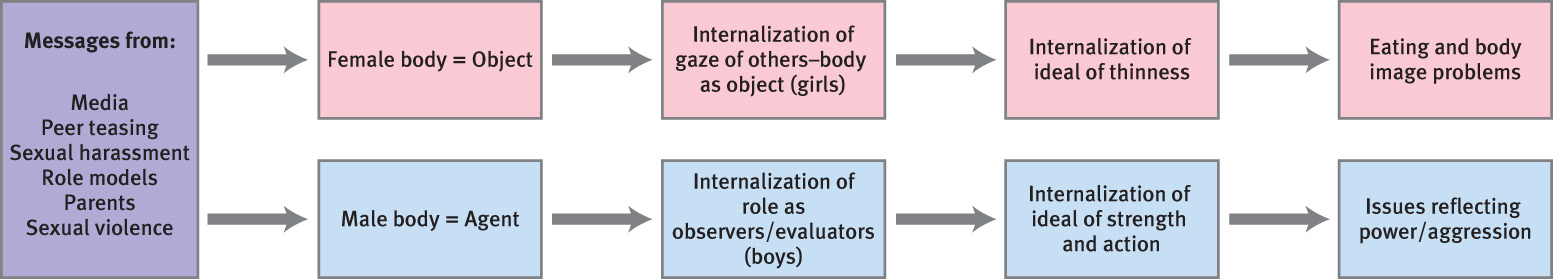

Objectification Theory: Explaining the Gender Difference

Objectification theory The theory that girls learn to consider their bodies as objects and commodities.

Objectification theory posits that girls learn to consider their bodies as objects and commodities, which explains how the cultural ideal of thinness makes women vulnerable to eating disorders (Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997). Western culture promotes the view of male bodies as agents—instruments that perform tasks—and of female bodies as objects mainly to be looked at and evaluated in terms of appearance (see Figure 10.5). Marya Hornbacher recounted her sense of being objectified:

I remember the body from the outside in…. There will be copious research on the habit of women with eating disorders perceiving themselves through other eyes, as if there were some Great Observer looking over their shoulder. Looking, in particular, at their bodies and finding, more and more often as they get older, countless flaws.

(1998, p. 14)

Implicit in Hornbacher’s musings about her perceptions of her body is the sense of her body as an object—to be looked at and evaluated and, all too frequently, found defective.

According to the theory, objectification encourages eating disorders because female bodies are evaluated according to the cultural ideal, and girls and women strive to have their bodies conform so that they will be positively evaluated. As they internalize the ideal of thinness, they increase their risk for eating disorders (Calogero et al., 2005; Thompson & Stice, 2001)—especially in combination with learning to see their bodies as objects from the outside: If they hold an ideal of thinness and see their bodies as objects, they become more likely to pay attention to their flaws and to feel ashamed of their bodies, and these feelings motivate restrained eating (Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997; Moradi et al., 2005). Even preschool children attribute more negative qualities to fat women than to fat men (Turnbull et al., 2000).

© Alisha Marie Ragland

Another possible explanation for the gender difference in prevalence rates of eating disorders focuses on the politics of a cultural ideal of thinness for women. Some researchers note that as women’s economic and political power has increased, female models have become thinner and less curvaceous, creating a physical ideal of womanhood that is harder—if not impossible—to meet. Women then spend significant time, energy, and money trying to emulate this thinner ideal through exercise, diet, medications, and even surgery, which in turn dissipates their economic and political power (Barber, 1998; Bordo, 1993).

317

Although today males are much less likely to develop any type of eating disorder than are women, this large gender discrepancy may not last. Data suggest that male physical ideals are increasingly unrealistic: Male film stars and Mr. Universe winners are increasingly muscular (Pope, Phillips, & Olivardia, 2000), paralleling the changes in women’s bodies in the media. Just as females covet bodies similar to those promoted in the media, so do males (Ricciardelli et al., 2006): Two thirds of men want their bodies to be more similar to cultural ideals of the male body (McCabe & Ricciardelli, 2001a, 2001b; Ricciardelli & McCabe, 2001). However, rather than suffer from the specific sets of symptoms for anorexia or bulimia, males are more likely to develop a form of “other” eating disorder, with symptoms that focus on muscle building, either through excessive exercise or steroid use (Weltzin et al., 2005). Sam, in Case 10.5, is preoccupied with losing muscle mass.

CASE 10.5 • FROM THE INSIDE: An “Other” Eating Disorder

Forty-year-old Sam recounts his preoccupations with his muscles:

I would get up in the morning and already wonder whether I lost muscle overnight while sleeping. I would rather be thinking about the day and who I was going to see, et cetera. But instead, the thoughts always centered on my body. Throughout the day, I would think about everything I ate, every physical movement I did, and whether it contributed to muscle loss in any way. I would go to bed and pray that I would wake up and think about something else the next day. It’s a treadmill I can’t get off of.

(Olivardia, 2007, pp. 125–126)

Feedback Loops in Understanding Eating Disorders

As we have seen, many neurological, psychological, and social factors are associated with the development and maintenance of eating disorders. In what follows we look at some theories about how these factors interact through feedback loops.

Most females in Western societies are exposed to images of thin women as ideals in the media, but only some women develop an eating disorder. Why? Neurological factors (such as a genetic vulnerability) may make some people more susceptible to the psychological and social factors related to eating disorders (Bulik, 2005). For instance, researchers hypothesize that young women who are prone to anxiety (neuroticism)—which is both a psychological factor and a neurological factor—are more susceptible to the effects of a familial focus on appearance, a social factor (Davis et al., 2004). Indeed, after statistically controlling for body size, researchers found that young women who were preoccupied with weight were more prone to anxiety and were more likely to have families that focused on appearance. This preoccupation both could result from anxiety and familial focus on appearance and could cause these effects. A preoccupation with weight can also lead to dieting, which can create its own neurochemical changes (neurological factor) that may lead to eating disorders (Walsh et al., 1995). In addition, the stringent rules that people may set for a diet can lead them to feel out of control with eating if they “violate” those rules (psychological factor). Further, people with higher levels of perfectionism and body dissatisfaction (psychological factors) may elicit comments about their appearance (social factor) or pay more attention to appearance-related comments (psychological factor) (Halmi et al., 2000). Figure 10.6 illustrates the feedback loops for eating disorders.

318

Thinking Like A Clinician

Suppose scientists discover genes that are associated with eating disorders. What could—and couldn’t—you infer about the role of genetics in eating disorders? How could genes contribute to eating disorders if bulimia is a relatively recent phenomenon? In what ways does the environment influence the development of eating disorders? Why do only some people who are exposed to familial and cultural emphases on weight, food, and appearance develop an eating disorder?