10.5 Treating Eating Disorders

One important goal when treating a patient with anorexia is to help her attain a medically safe weight by helping her to eat more and/or purge less often; if that safe weight cannot be reached with outpatient treatment (treatment that does not involve an overnight stay in a hospital), then inpatient treatment becomes imperative. Inpatient treatment occurs in a psychiatric hospital or psychiatric unit of a general hospital; inpatient treatment for eating disorders may also take place at special stand-alone facilities.

319

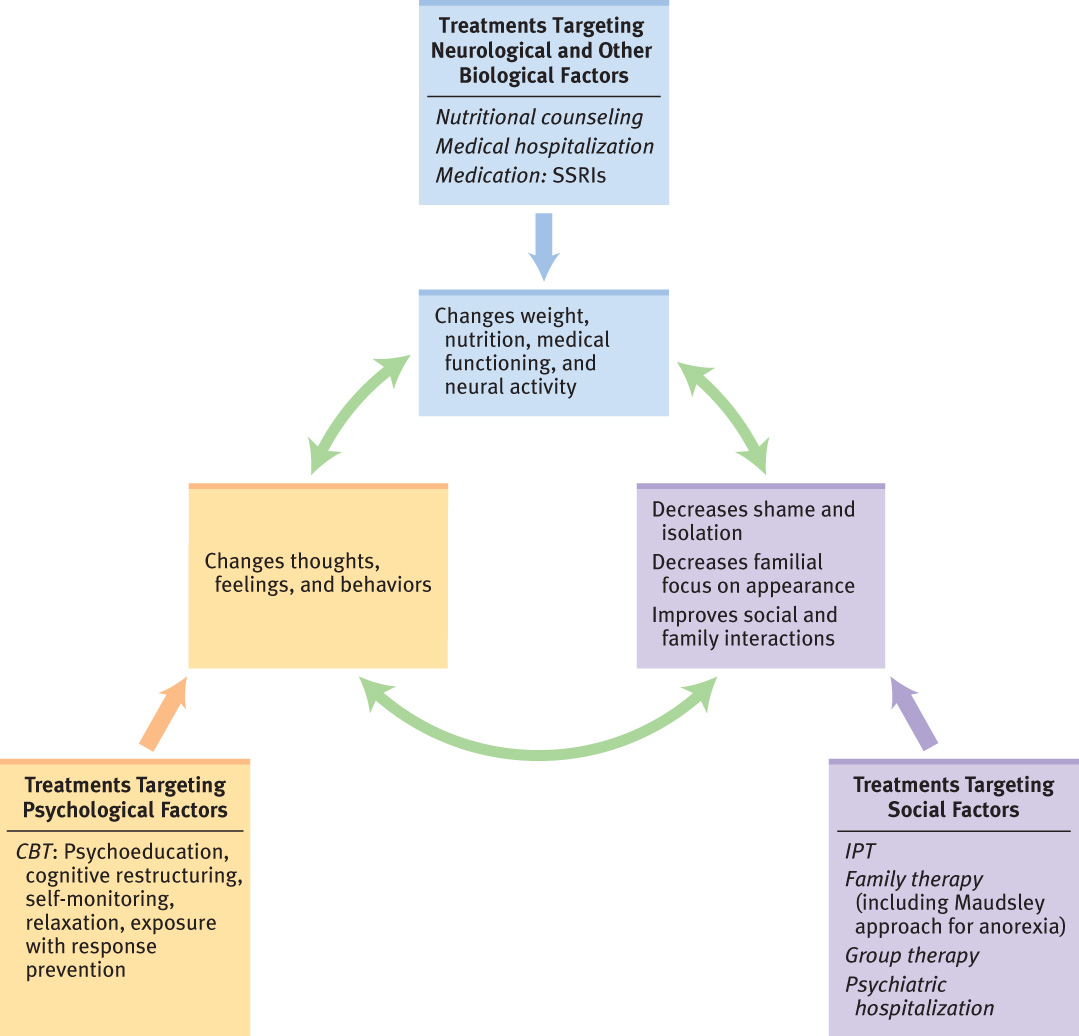

When someone with an eating disorder isn’t underweight enough to require inpatient treatment, many different factors can be the initial targets of treatment. In this section we examine specific treatments that target neurological (and biological, more broadly), psychological, and social factors and the role of hospitalization.

As with treatment for other disorders, the intensity of treatment for eating disorders can range from hospitalization, to day or evening programs, to residential treatment (staffed facilities in which patients sleep, take breakfast and dinner, and perhaps participate in evening groups), to weekly visits with a therapist. In all these forms of treatment, cognitive-behavior therapy (CBT) is generally considered the method of choice. Regardless of the severity of the eating disorder, frequent visits with an internist or a family doctor are an important additional component of treatment. The physician determines whether a patient should be medically hospitalized and, if not, whether she is medically stable enough to partake in daily activities. In what follows, we examine treatment options from the neuropsychosocial perspective.

Targeting Neurological and Biological Factors: Nourishing the Body

Neurologically and biologically focused treatments are designed to create a pattern of normal healthy eating and to stabilize medical problems that arise from the eating disorder. Treatments that focus specifically on these goals include nutritional counseling to improve eating, medical hospitalization to address significant medical problems, and medication to diminish some symptoms of the eating disorder as well as symptoms of comorbid anxiety and depression.

A Focus on Nutrition

For people with any type of eating disorder, increasing the nutrition and variety of foods eaten—and not purged—is critical. A nutritionist will help develop meal plans for increasing caloric intake at a reasonable pace. In the process of nutritional counseling, the nutritionist may identify a patient’s mistaken beliefs about food and weight; the nutritionist then seeks to educate the patient and thus help her correct such beliefs. As people with anorexia begin to eat more, they may experience gastrointestinal discomfort: Because of a lack of body fat, having more food in the gastrointestinal system may compress a section of the duodenum (a part of the intestine) that is on top of an important artery (Adson et al., 1997). The discomfort goes away as she recovers.

Medical Hospitalization

The bodily effects of eating disorders—particularly anorexia—can be directly life-threatening. When medical problems related to eating disorders become severe, a medical hospitalization rather than a psychiatric hospitalization may be necessary. Medical hospitalization generally occurs in response to a medical crisis, such as a heart problem, gastrointestinal bleeding, or significant dehydration. The goal of medical hospitalization is to treat the specific medical problem and stabilize the patient’s health.

Medication

Generally, medications do not help people with anorexia gain weight (Crow et al., 2009; Walsh et al., 2006). However, once the patient’s normal weight is restored, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) may help prevent the person from developing anorexia again (Barbarich et al., 2004).

For bulimia, antidepressants—particularly SSRIs—may reduce some symptoms of the eating disorder. Compared to placebos, SSRIs can help decrease bingeing, vomiting, and weight and shape concerns, although other symptoms may still persist—including a fear of normal eating (Bacaltchuk et al., 2000; Mitchell et al., 2001). SSRIs may also reduce symptoms of comorbid depression. The SSRI Prozac (fluoxetine) is the most widely studied medication for bulimia, and the FDA has approved it to treat this disorder. Studies of the effects of Prozac on bulimia typically last no longer than 16 weeks, however, so it isn’t clear how long the medication should be taken (de Zwaan et al., 2004). Moreover, as with other disorders, the beneficial effects of medication used to treat eating disorders typically stop soon after the medication is discontinued.

320

Targeting Psychological Factors: Cognitive-Behavior Therapy

CBT is the most widely studied treatment of eating disorders that directly targets psychological factors, and it is considered the treatment of choice (Pike et al., 2004). CBT for eating disorders focuses primarily on changes in thoughts, feelings, and behaviors that are related to eating, food, and the body, at least in the initial stages. At the outset of treatment, the patient and therapist discuss who monitors the patient’s weight and at what point inpatient treatment would be recommended and pursued (Pike et al., 2004).

CBT for Anorexia

CBT can be effective in reducing symptoms of anorexia and has been shown to prevent relapses (Pike et al., 2003). CBT for anorexia focuses on identifying and changing thoughts and behaviors that impede normal eating and that maintain the symptoms of the disorder. Cognitive restructuring can decrease the patient’s irrational thoughts (such as the belief that starving means having self-control) and help the patient to develop more realistic thoughts (for example, that appropriate eating indicates the ability to care for herself). The therapist also helps the patient to develop more adaptive coping strategies (Bowers & Ansher, 2008; Garner et al., 1997; Wilson & Fairburn, 2007), such as expressing anger or disappointment directly to other people rather than hiding or denying such “negative” feelings. Treatment may also involve psychoeducation (about the disorder and its effects), training in self-monitoring (to notice hunger cues and become aware of problematic behaviors), and relaxation training (to decrease anxiety that arises with increased eating). Because low weight can affect cognitive functioning, irrational thoughts may not change substantially until the patient’s weight increases (McIntosh et al., 2005).

CBT for Bulimia

The benefits of CBT for bulimia are well documented (Agras, Crow, et al., 2000; Ghaderi, 2006; Walsh et al., 1997). When used as a treatment for bulimia, CBT focuses on the thoughts, feelings, and behaviors that: (1) prevent normal eating; and (2) promote bingeing, purging, and other behaviors that are intended to offset the calories eaten during a binge. CBT also addresses thoughts, feelings, and behaviors that are related to body image and appearance and that maintain the symptoms of bulimia. In addition to focusing on symptoms of the disorder, CBT may address issues associated with perfectionism, low self-esteem, and mood (Wilson & Fairburn, 2007). CBT for bulimia uses many of the same methods as CBT for anorexia: psychoeducation, cognitive restructuring, self-monitoring, and relaxation. In addition, treatment may employ a method used to treat obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD): exposure with response prevention (discussed in Chapter 7). For bulimia, this method generally involves exposing the patient to anxiety-provoking stimuli, such as foods she would typically eat only during a binge. Patients are asked to consume a moderate amount of the binge food during a therapy session (the exposure), and the response prevention involves not purging or responding in another usual way to compensate for the calories taken in.

321

Efficacy of CBT for Treating Eating Disorders

Most people with eating disorders who improve significantly with CBT do so within the first month of treatment (Agras, Crow, et al., 2000). However, although CBT helps decrease their bingeing, purging, and dieting behaviors, up to 50% of patients retain some symptoms after the treatment ends (Lundgren et al., 2004). One study of 48 patients who completely abstained from bingeing and purging after CBT found that 44% had relapsed 4 months later (Halmi et al., 2002). Various factors predicted which people relapsed, including more eating rituals, more food-related thoughts, and less motivation to change; stressful life events can also precipitate relapses (Grilo et al., 2012). Although CBT may be the treatment of choice and helps many people with eating disorders, it clearly isn’t a panacea.

Targeting Social Factors

Given the important role that social factors play in contributing to eating disorders, it is not surprising that various effective treatments directly target these factors. Treatments that target social factors include interpersonal therapy, family therapy, group-based inpatient treatment programs, and prevention programs.

Interpersonal Therapy

A manual-based form of interpersonal therapy (IPT) has been applied to eating disorders; this version of IPT includes 4 to 6 months of weekly therapy (Fairburn, 1998; Wilfley et al., 2012). In any form of IPT, the focus is on problems in relationships that contribute to the onset, maintenance, and relapse of the disorder (Frank & Spanier, 1995; Klerman & Weissman, 1993). Although IPT was originally developed to treat depression, the central idea behind IPT for eating disorders is that as problems with relationships resolve, symptoms decrease, even though the symptoms are not addressed directly by the treatment (Tantleff-Dunn et al., 2004).

How does IPT work to treat eating disorders? The hypothesized mechanism is as follows: (1) IPT reduces longstanding interpersonal problems; (2) the resulting improvement of relationships makes people feel hopeful and empowered and increases their self-esteem; and, (3) these changes lead people to change other aspects of their lives, such as disordered eating; moreover, they lead to less concern about appearance and weight and, therefore, less dieting and bingeing (Fairburn, 1997).

Although IPT for anorexia has not yet been well researched, many studies have shown that IPT is an effective alternative to CBT for bulimia (Apple, 1999; Fairburn, 1997, 2005; Tanofsky-Kraff & Wilfley, 2010).

Family Therapy

Maudsley approach A family treatment for anorexia nervosa that focuses on supporting parents as they determine how to lead their child to eat appropriately.

The most widely used family-oriented treatment for anorexia is called the Maudsley approach (Dare & Eisler, 1997; le Grange & Eisler, 2009; Lock, Le Grange, et al., 2001), named after the hospital in which the treatment originated. This approach, most effective for young women and girls who live with their parents, does not view the family as responsible for causing problems and in fact makes no assumptions about the causes of the disorder. Instead, the Maudsley approach focuses on: (1) helping parents view the patient as distinct from her illness; and (2) supporting the parents as they figure out how to lead their daughter to eat appropriately. The therapist asks the parents to unite to feed their daughter, despite her anxiety and protests. Once her weight is normal and she eats without a struggle, they gradually return control to her, and other family issues—including general ones of adolescent development—become the focus (Lock, 2004). The initial phase of treatment requires an enormous commitment on the part of the family: A parent must be home continuously to monitor the daughter’s eating. Clearly, the Maudsley approach is not feasible for all families. But research results indicate that it is perhaps the most effective treatment for adolescents and young adults with anorexia (Keel & Haedt, 2008).

322

In addition, systems therapy is one type of family therapy provided to young women and girls with eating disorders. In this therapy, the family is viewed as a system; when one member changes, change is forced on the rest of the system (Bowen, 1978; Minuchin, 1974). Maladaptive family interactional patterns and structures are seen as the problem and are the focus of change. With family systems therapy, the therapist may not specifically address the patient’s eating and food issues.

Psychiatric Hospitalization

In contrast to medical hospitalizations, psychiatric hospitalizations (also called inpatient treatment) for eating disorders are often planned in advance, and they usually take place in units or free-standing facilities that specialize in treating people with eating disorders. Psychiatric hospitalization is recommended when less intensive treatments have failed to change disordered eating behaviors sufficiently. The hospital environment is a 24-hour community in which patients attend many different types of group therapy, including groups focused on body image, coping strategies, and relationships with food. These groups can decrease the isolation and shame patients may feel and give patients an opportunity to try out new ways of relating. Hospitalized patients also receive individual therapy and usually some type of family therapy; patients may also receive medication.

GETTING THE PICTURE

@Dieter Heinemann/Westend61/Corbis

The short-term goals of psychiatric hospitalization for anorexia and bulimia include increasing the person’s weight to the normal range, establishing a normal eating pattern (three full meals and two snacks per day), curbing excessive exercise, and beginning to change irrational, maladaptive thoughts about food, weight, and body shape. For people who purge or otherwise try to compensate for their caloric intake, an additional goal is to stop or at least reduce such compensatory behaviors.

Psychiatric hospitalization can improve eating and help to change distorted thoughts about food, weight, and body. But, in many cases, these positive changes are not enduring. Twelve months after discharge from a psychiatric hospital, 30–50% of patients relapse (Helverskov et al., 2010; Pike, 1998). Consider that in 1 year, Marya Hornbacher was hospitalized three times.

Various explanations have been proposed for the high relapse rate. One is that some patients only accept the intensive treatment for health reasons or because of pressure from family members—and once out of the hospital, they are not willing to continue the changes they began.

A second reason for the high relapse rate after psychiatric hospitalization is that some patients do not receive appropriate outpatient care after they leave the hospital. This lack of care makes it more difficult for them to learn how to sustain their changed eating, weight, and views about their bodies when they are not in a supervised therapeutic environment.

A third reason for the high relapse rate focuses on economic pressures from insurance companies, which have cut the approved length of hospital stays for people with eating disorders (and for people with psychological disorders in general). Psychiatric hospitalizations have become increasingly short, which reduces the amount of enduring change that can realistically be accomplished during a stay.

323

Prevention Programs

Many mental health clinicians and researchers seek to prevent eating disorders, particularly for people most at risk (Coughlin & Kalodner, 2006; Shaw et al., 2009): namely, people who have some symptoms of an eating disorder but do not meet all the diagnostic criteria. Prevention programs often seek to challenge maladaptive beliefs about appearance and food and to decrease overeating, fasting, and avoidance of some types of foods (Stice et al., 2013). Prevention programs may take place in a single session or in multiple sessions, may take the form of presentations or workshops, or may even be provided via the Internet (Zabinski et al., 2001, 2004).

Feedback Loops in Treating Eating Disorders

With all eating disorders, successful treatment should resolve medical crises and normalize eating and nutrition, directly or indirectly. For a person with anorexia, this means increasing her eating. Better nutrition leads to improved brain functioning (neurological factor) and cognitive functioning (psychological factor). For a person with bulimia, it means normalizing her meals—making sure that she is not only eating adequately throughout the day but also getting enough of the various food groups. Eating in this way will decrease the likelihood of extreme hunger, binges, or eating that feels out of control (psychological factor) (Shah et al., 2005).

324

In most cases, enduring changes in eating result from changes in the way the person thinks about food and her beliefs about weight, appearance, femininity, and control. CBT may contribute to these enduring changes (psychological factor). In addition, the support of family and friends and the improved quality of these relationships, which may come from IPT or family therapy (social factor), can help the patient more realistically evaluate her appearance, weight, and body shape. Improved family interaction patterns can increase mood and satisfaction with relationships, which can decrease the level of attention that the person pays to cultural pressures toward an ideal body shape (psychological factor). The feedback loops involved in treating eating disorders are shown in Figure 10.7.

Thinking Like A Clinician

Suppose your local hospital establishes an eating disorders treatment program. Based on what you have learned in this chapter, what services should it offer, and why? If your friend, who has bulimia nervosa, asked your advice about what type of treatment she should get, how would you respond, and why?