11.1 Gender Dysphoria

Last year, Mike got a Facebook status update from Sam, his friend since high school. Sam announced that he’d become Samantha; he had begun to dress and live as a woman. The news, and Samantha’s new Facebook photo, took Mike by surprise. Sam had dated girls occasionally in high school—they’d even gone out on double dates together—and Sam seemed so “normal.” In the Facebook photo, Mike found Samantha only vaguely recognizable as having been Sam. Mike didn’t know how to make sense of Sam’s change. Mike told Laura about Sam’s change to Samantha, and Mike found himself wondering what life—and sex—had been like for Sam, and what it was like now for Samantha. What had happened, or would happen, to Sam’s genitals? What in the world could have driven Sam to want to make such a drastic change? Mike surfed the Internet for reputable information about Sam’s condition and discovered that it is called gender dysphoria.

What Is Gender Dysphoria?

Gender identity The subjective sense of being male or female (or having the sense of a more fluid identity, outside the binary categories of male and female), as these categories are defined by a person’s culture.

Like Sam, a small percentage of people at birth are (usually based on their observable sex organs) assigned one gender (either female or male) but do not feel comfortable with the corresponding gender identity. Gender identity is the subjective sense of being male or female (or having the sense of a more fluid identity, outside the binary categories of male and female), as these categories are defined by a person’s culture. For instance, people like Sam, who have male sexual anatomy and have been labeled male since birth, may feel as if they are female. Conversely, some people have been labeled as female since birth but feel as if they are male. (The gender that a person is assigned at birth is referred to as the natal gender.) People who feel that their gender identity does not correspond to their natal gender thus experience cross-gender identification.

329

Gender dysphoria A psychological disorder characterized by an incongruence between a person’s assigned gender at birth and the subjective experience of his or her gender, and that incongruence causes distress.

Transgender is a broad term sometimes used to describe people whose identification and behavior may be at odds with their natal gender but who do not necessarily seek medical treatment to change their sexual characteristics (Riley et al., 2013). If such people live as the “opposite gender” (e.g., a natal male dresses in daily life and is known by others as a female), they are referred to as transsexuals. Transsexuals may seek medical treatment to attain sexual characteristics that match their experienced gender. Gender dysphoria is an incongruence between a person’s assigned gender (usually based on his or her natal gender) and the subjective experience of his or her gender, and that incongruence causes distress (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

Gender role The outward behaviors, attitudes, and traits that a culture deems masculine or feminine.

Gender dysphoria typically begins in childhood; children who are diagnosed with gender dysphoria usually strongly desire to be the opposite gender of their assigned one, preferring to dress or play with toys in ways that are typical of children of the other gender. That is, they wish to behave in accordance with the prototypical gender role of their experienced gender, not their assigned, natal gender; gender role refers to the outward behaviors, attitudes, and traits that a culture deems masculine or feminine. For instance, gender roles for females often allow a wider variety of emotions (anger, tears, and fear) to be displayed in public than do gender roles for males; in contrast, gender roles for males often allow more overtly aggressive or assertive behaviors than do gender roles for females. A person with gender dysphoria wants to adopt the gender role of the opposite gender not because of perceived cultural advantages of becoming the other gender but because the opposite gender role is more consistent with the person’s sense of self.

In children, gender dysphoria is not simply “tomboyishness” in girls or “sissy” behavior in boys. Rather, gender dysphoria reflects a profound sense of identifying with the other gender, to the point of denying one’s own sexual organs. For instance, natal girls with gender dysphoria report that they don’t want to develop breasts or menstruate. However, long-term studies of children who have been diagnosed with gender dysphoria find that most of the children did not continue to have the disorder into adulthood (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Drummond et al., 2008; Zucker, 2005).

TABLE 11.1 lists the criteria for gender dysphoria in children, and TABLE 11.2 lists the criteria for the disorder in adolescents and adults. Adolescents and adults may feel uncomfortable living publicly as their assigned, natal gender. In fact, these people may be preoccupied by the wish to be the other gender. They may take that wish further and live, at least some of the time, as someone of the other gender—dressing and behaving accordingly, whether at home or in public. Like Sam, some adults with gender dysphoria have medical and surgical treatments to assume the appearance of the other sex; such surgical procedures are called sex reassignment surgery (discussed in the section on treatment).

|

| Reprinted with permission from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, (Copyright ©2013). American Psychiatric Association. All Rights Reserved. |

|

| Reprinted with permission from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, (Copyright ©2013). American Psychiatric Association. All Rights Reserved. |

330

In order for a person to be diagnosed with gender dysphoria, DSM-5 requires that the symptoms cause significant distress or impair functioning. However, the distress experienced by someone with gender dysphoria often arises because of other people’s responses to the cross-gender behaviors (Nuttbrock et al., 2010; Roberts et al., 2012). For instance, a natal male child with gender dysphoria may be ostracized or made fun of by children or even teachers for consistently “playing girl games”—and thus the child feels distress because of the reactions of others. In contrast, for most disorders in DSM-5, the distress that the person feels arises directly from the symptoms themselves (e.g., distress that is caused by feeling hopeless or being afraid in social situations).

Like the person in Case 11.1, most adolescents and adults with gender dysphoria report having had symptoms of the disorder in childhood—even though most people who had gender dysphoria in childhood do not have it later in life.

CASE 11.1 • FROM THE INSIDE: Gender Dysphoria

In her memoir She’s Not There: A Life in Two Genders (2003), novelist and English professor Jenny Finney Boylan (who was born male) describes her experiences of feeling, since the age of 3, as if she were a female in a male body:

Since then, the awareness that I was in the wrong body, living the wrong life, was never out of my conscious mind—never, although my understanding of what it meant to be a boy, or a girl, was something that changed over time. Still, this conviction was present during my piano lesson with Mr. Hockenberry, and it was there when my father and I shot off model rockets, and it was there years later when I took the SAT, and it was there in the middle of the night when I woke in my dormitory at Wesleyan. And at every moment I lived my life, I countered this awareness with an exasperated companion thought, namely, Don’t be an idiot. You’re not a girl. Get over it.

But I never got over it.

(pp. 19–21)

331

Bob Barkany/Getty Images

Most commonly, people with gender dysphoria are heterosexual relative to their gender identification. For instance, natal men who see themselves as women tend to be attracted to men and thus feel as if they are heterosexual (Blanchard, 1989, 1990; Zucker & Bradley, 1995). However, some are homosexual relative to their gender identification; a natal woman who sees herself as a man may be sexually attracted to men. And some people with gender dysphoria are bisexual and some are asexual—they have little or no interest in any type of sex.

As noted in TABLE 11.3 (along with other facts about gender dysphoria), gender dysphoria is about three times more common among natal males than among natal females. One explanation for this difference is that in Western cultures, females have a relatively wide range of acceptable “masculine” behavior and dress (think of Diane Keaton’s character in the move Annie Hall), whereas males have a relatively narrow range of acceptable “feminine” behavior and dress. A woman dressed in “men’s” clothes might not even get a second look, but a man dressed in “women’s” clothes will likely be subjected to ridicule.

| Prevalence |

|

| Comorbidity |

|

| Onset |

|

| Course |

|

| Gender Differences |

|

| Cultural Differences |

|

| Source: Unless otherwise noted, information is from American Psychiatric Association, 2013. |

Understanding Gender Dysphoria

As summarized in the following sections, we now know that various neurological, psychological, and social factors are associated with gender dysphoria.

332

Neurological Factors

Researchers have begun to document differences in specific brain structures in people who have gender dysphoria versus those who do not. In addition, evidence shows that hormones during fetal development play a role in producing this disorder. Genes can also play a large role in contributing to this disorder.

Brain Systems and Neural Communication

The brains of transsexuals differ from typical brains in ways consistent with their gender identity. In particular, Kruijver and colleagues (2000) examined a specific type of neuron in a brain structure called the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis (which is often regarded as an extension of the amygdala). Typically, males have almost twice as many of these neurons as females do. In this study, the number of these neurons in the brains of male-to-female transsexuals was in the range typically found in female brains, and the number in the brains of female-to-male transsexuals was in the range typically found in male brains.

How might such brain alterations arise? Research suggests that prenatal exposure to hormones may affect later gender identity (Bradley & Zucker, 1997; Wallien et al., 2008; Zucker & Bradley, 1995). In particular, maternal stress during pregnancy can produce hormones that alter brain structure and thereby predispose a person to gender dysphoria (Zucker & Bradley, 1995). In addition, fetal levels of testosterone—measured from amniotic fluid—are positively associated with later stereotypical “male” play behavior in girls and, to a lesser extent, in boys; the higher the level of testosterone in the fluid, the more “male” play the children exhibited when they were between 6 and 10 years old (Auyeung et al., 2009).

Genetics

Coolidge and colleagues (2002) studied 314 children who were either identical or fraternal twins and concluded that as much as 62% of the variance in gender dysphoria can arise from genes! If this result is replicated, it will provide strong support for these researchers’ view that the disorder “may be much less a matter of choice and much more a matter of biology” (p. 251). However, even in this study, almost 40% of the variance was ascribed to the effects of nonshared environment, and thus genes—once again—are not destiny.

In short, neurological factors—brain differences, prenatal hormones, and genetic predispositions—may contribute to gender dysphoria, but the presence of any one of these factors does not appear to be sufficient to cause this disorder (Di Ceglie, 2000).

Psychological Factors: A Correlation with Play Activities?

In general, studies have found that boys engage in more rough-and-tumble play and have a higher activity level than do girls. Natal boys with gender dysphoria, however, do not have as high an activity level as their counterparts without the disorder. Similarly, natal girls with gender dysphoria are more likely to engage in rough-and-tumble play than are other girls (Bates et al., 1973, 1979; Zucker & Bradley, 1995). Both natal boys and natal girls with gender dysphoria are less likely to play with same-sex peers; instead, they seek out, feel more comfortable with, and feel themselves to be more similar to children of the other sex (Green, 1974, 1987).

However, such findings should be interpreted with caution, for two reasons: (1) These very characteristics are part of the diagnostic criteria for gender dysphoria in children, so it is not at all surprising that these behaviors are correlated with having the disorder; (2) a diagnosis of gender dysphoria in childhood does not usually persist into adulthood. Thus, beyond symptoms that are part of the criteria for gender dysphoria, no psychological factors are clearly associated with the disorder.

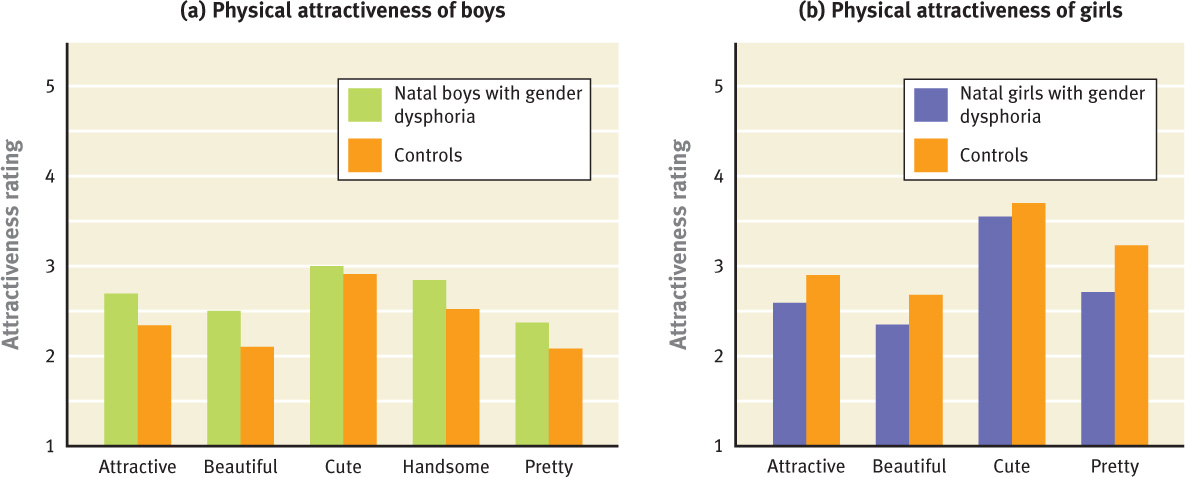

Social Factors: Responses From Others

Social factors may be associated with gender dysphoria, but such factors are unlikely to cause the disorder (Bradley & Zucker, 1997; Di Ceglie, 2000). As shown in Figure 11.1(a), college students rated photographs of natal boys with gender dysphoria as cuter and prettier than photos of boys without the disorder; in contrast, Figure 11.1(b) shows that natal girls with gender dysphoria were rated as less attractive than girls who did not have the disorder (Zucker et al., 1993). These contrasting ratings of physical appearance may reflect the prenatal influence of hormones: Natal boys may have been exposed to more female hormones in the womb, leading to the feminization of their facial features; conversely, natal girls may have been exposed to more male hormones in the womb, leading to the masculinization of their facial features. In turn, the feminized or masculinized facial features may lead others to interact differently with people who then develop this disorder.

333

Given how little is known about the factors that contribute to gender dysphoria, we cannot comment on the nature of any feedback loops among them.

Treating Gender Dysphoria

Treatments for gender dysphoria may target all three types of factors.

Targeting Neurological and Other Biological Factors: Altered Appearance

Sex reassignment surgery A procedure in which a person’s genitals (and breasts) are surgically altered to appear like those of the other sex.

One way for people with gender dysphoria to achieve greater congruence between the gender they feel themselves to be and their natal gender is to alter some or all of their biological sexual characteristics. This sort of treatment may involve taking hormones. In natal women, taking male sex hormones will lower the voice, stop menstruation, and begin facial hair growth. In natal men, taking female sex hormones will enlarge breasts and redistribute fat to the hips and buttocks.

Some people with gender dysphoria go a step further and have sex reassignment surgery, a procedure in which the genitals and breasts are surgically altered to appear like those of the other gender. Sex reassignment surgery for natal males involves creating breasts and removing most of the penis and testes and then creating a clitoris and vagina. For natal females, surgery involves removing breasts, ovaries, and uterus and then creating a penis. Patients may also have subsequent surgeries to make their facial features more similar to those of the other gender. However, these surgical treatments can—like other forms of surgery—be risky and prohibitively expensive.

334

Sex reassignment surgery is technically more effective for natal men than for natal women, in part because it is difficult to create an artificial penis that provides satisfactory sexual stimulation (Steiner, 1985). Regardless of natal gender, however, most people who have gender dysphoria are satisfied with the outcome of their sex reassignment surgery, despite possible difficulty in attaining orgasm (Cohen-Kettenis & Gooren, 1999; Smith, van Goozen, et al., 2005). However, up to 10% of people who have this surgery (depending on the study) later regret it (Landen et al., 1998; Smith van Goozen, et al., 2001). Factors associated with a less positive outcome after surgery include having unsupportive family members (Landen et al., 1998) and having a comorbid psychological disorder (Midence & Hargreaves, 1997; Smith, van Goozen, et al., 2005).

In an effort to reduce the proportion of people who come to regret having sex reassignment surgery, those contemplating it are usually carefully evaluated beforehand regarding their emotional stability and their expectations of what the surgery will accomplish. A careful diagnostic evaluation and a long period of cross-dressing are required by most facilities before sex reassignment surgery.

Targeting Psychological Factors: Understanding the Choices

Treatment that targets psychological factors helps people with gender dysphoria not only to understand themselves and their situation but also to be aware of their options and goals regarding living publicly as the other gender; treatment also provides information about medical and surgical options. Such treatment is typically provided by mental health clinicians specially trained in diagnosing and helping people with gender dysphoria. These clinicians also help patients identify and obtain treatment for any other mental health issues, such as depression or anxiety (Carroll, 2000). For those who choose to live part time or full time as the other gender, the clinician helps them discover whether doing so is in fact more consistent with how they feel and how they see themselves. Moreover, the clinician helps the patient with problem solving related to living as the other gender—such as by identifying and developing possible solutions to issues that might arise regarding other people’s responses to their changed gender.

Targeting Social Factors: Family Support

Family members of people with gender dysphoria may not understand the disorder or know how to be supportive; family therapy techniques that focus on communication and educating the family about gender dysphoria can help family members develop more effective ways to discuss problems.

In addition, groups for people with gender dysphoria can provide support and information. Group therapy may also focus on difficulties in relationships or problems that arise as a result of living as the other gender, such as experiencing sexual harassment for those newly living as a woman or taunting by men for those newly living as a man (Di Ceglie, 2000).

Treatment for gender dysphoria typically first targets psychological factors—helping people to determine whether they want to live as the other gender. If they decide to do so, then treatment targeting social factors comes into play, to address problems with family members and interactions with other people in general. Following this, treatment targeting neurological and other biological factors is provided when a person wishes to have medical or surgical procedures. After such treatment, clinicians may provide additional treatment that targets psychological and social factors.

335

Thinking Like A Clinician

When Nico was a boy, he hated playing with the other boys; he detested sports and loved playing “house” and “dress up” with the girls—except when the girls made him dress up as “the man” of the group. Sometimes he got to be the princess, and that thrilled him. As a teenager, Nico’s closest friends continued to be females. Although Nico shied away from playing with boys, he felt himself sexually attracted to them. To determine whether Nico had gender dysphoria, what information would a clinician want? What specific information would count heavily? Should the fact that Nico is attracted to males affect the assessment? Why or why not?