11.3 Sexual Dysfunctions

Let’s return to Laura and Mike, the married couple whose relationship—and sex life—had become strained. Laura found that she didn’t particularly miss having sexual relations with Mike. In fact, Laura didn’t have any sex drive, and the past few times she and Mike had made love, nothing had “happened” for her—she hadn’t had an orgasm or even found herself aroused. She couldn’t pinpoint where things had gone astray; she’d like to feel desire, to want to have sexual relations with her husband, but she just didn’t know where to start or how to get herself worked up about it. Was there something wrong with their relationship, or with her? Or is such lack of interest “normal”?

An Overview of Sexual Functioning and Sexual Dysfunctions

Sexual dysfunctions Sexual disorders that are characterized by problems in the sexual response cycle.

People engage in sexual relations for two general reasons: to create babies (reproductive sex) and for pleasure (recreational sex). The vast majority of sexual acts are for pleasure, as opposed to procreation. Researchers have defined the “normal” progression of sexual pleasure as the human sexual response cycle, discussed in what follows. Sexual dysfunctions are characterized by problems in the sexual response cycle. We first examine this cycle and then consider various ways in which it can go awry for men and women.

347

The Normal Sexual Response Cycle

Sexual response cycle The four stages of sexual response—excitement, plateau, orgasm, and resolution—outlined by Masters and Johnson.

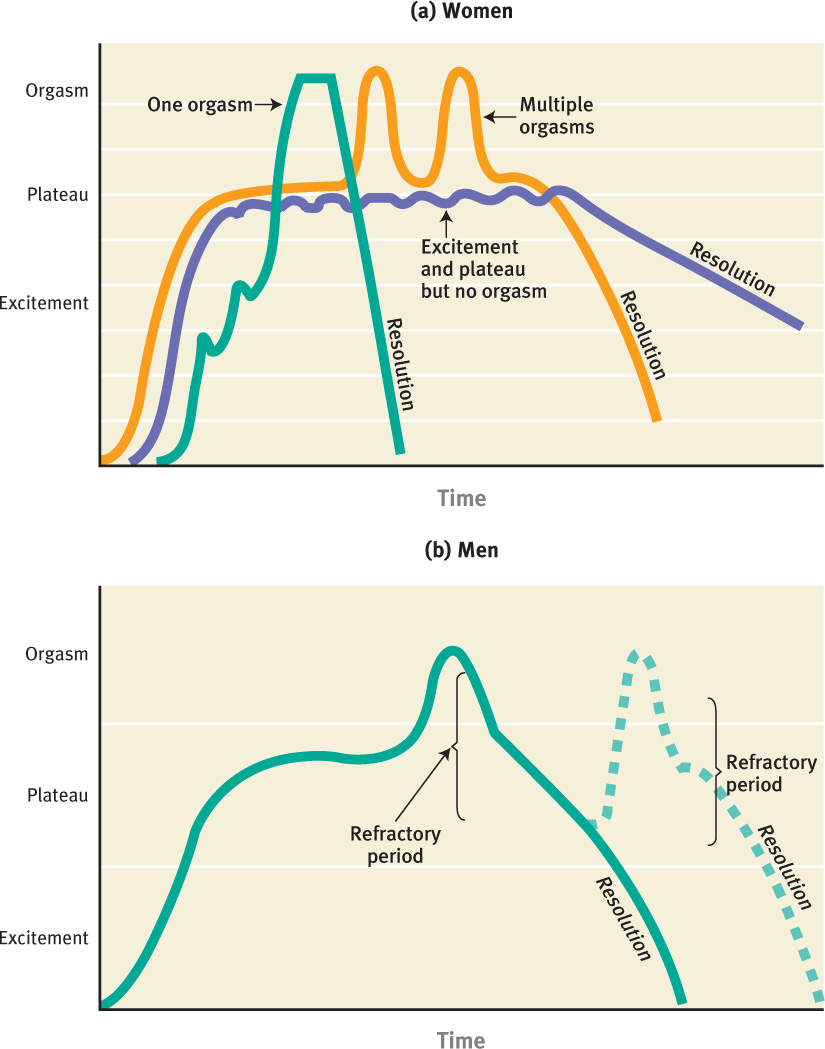

What is a normal sexual response? In the 1950s and 1960s, researchers William Masters and Virginia Johnson sought to answer this question by measuring the sexual responses of thousands of volunteers. Based on their research, Masters and Johnson (1966) outlined the sexual response cycle for both women and men as consisting of four stages (see Figure 11.2):

- Excitement. Excitement occurs in response to sensory-motor, cognitive, and emotional stimulation that leads to erotic sensations or feelings. Such arousal includes muscle tension throughout the body and engorged blood vessels, especially in the genital area. In men, this means that the penis swells; in women, this means that the clitoris and external genital area swell, and vaginal lubrication occurs.

- Plateau. Bodily changes that began in the excitement phase become more intense and then level off when the person reaches the highest level of arousal.

- Orgasm. The arousal triggers involuntary contractions of internal genital organs, followed by ejaculation in men. In women, responses range from extended or multiple orgasms (without falling below the plateau level) to resolution.

- Resolution. Following orgasm is a period of relaxation, of release from tension. For men, this period is often referred to as a refractory period, during which it is impossible to have an additional orgasm. Women rarely have such limitations and can often return to the excitement phase with effective sexual stimulation.

Although it is convenient to organize these events into stages, the boundaries between the stages are not clear-cut (Levin, 1994). In addition, other researchers have noted that before the excitement phase, the person must first experience sexual attraction, which should lead to sexual desire, which in turn leads to the first stage of the sexual response cycle: excitement (Kaplan, 1981). Desire consists of fantasies and thoughts about sexual activity along with an inclination or interest in being sexual. Sexual problems can occur when people experience a diminished—or even a lack of—sexual desire, or when they have difficulties related to sexual arousal or performance (the last three stages of sexual response). Laura appears to lack any sexual desire.

Disorders of sexual dysfunction are often divided into four categories: sexual desire disorders, sexual arousal disorders, orgasmic disorders, and sexual pain disorders. Many, if not most, problems in the sexual response cycle have psychological causes rather than physical causes relating to sex organs. These disorders can arise in people of various sexual orientations, such as heterosexuals, lesbians, gay men, or bisexuals.

348

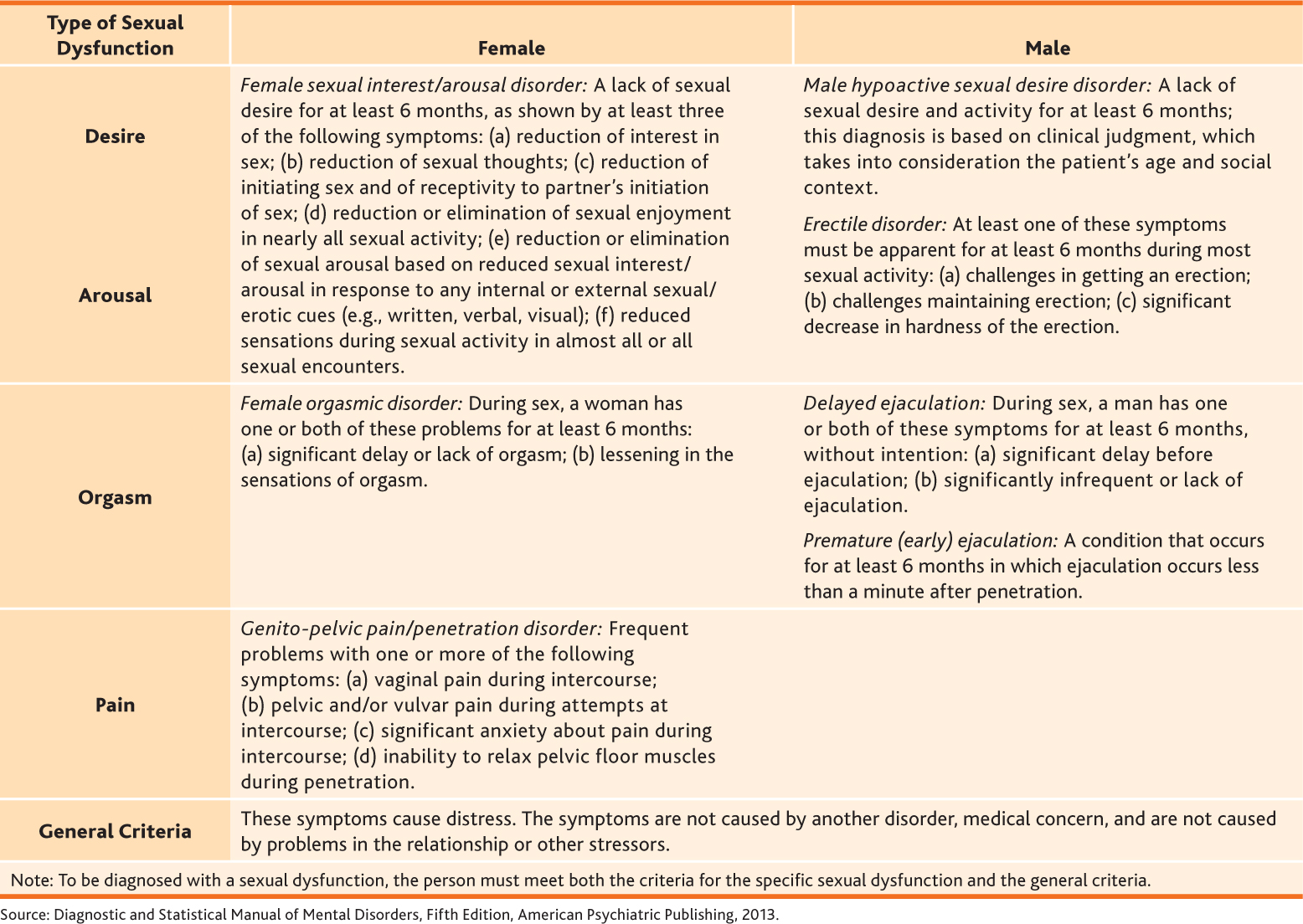

Sexual Dysfunctions According to DSM-5

A person can have more than one kind of sexual dysfunction, such as occurs when a man with premature ejaculation becomes nervous about having sexual relations and so develops a dysfunction of desire or arousal. Moreover, a sexual dysfunction may have existed for a person’s entire adult life (lifelong) or may have been acquired after a period of normal sexual functioning (acquired), as happened to Laura. In addition, the dysfunction may occur in all circumstances (generalized) or only in certain situations, with specific partners or types of stimulation (situational). TABLE 11.6 lists the DSM-5 sexual dysfunctions and their diagnostic criteria.

As noted in TABLE 11.6, for a sexual dysfunction to be considered a disorder, the sexual symptoms must cause significant distress or problems in relationships (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). This means that even though a person has a problem with an aspect of sexual response, he or she would not be diagnosed as having a sexual dysfunction disorder unless the problem caused marked distress or led to problems in his or her relationships. Case 11.6 illustrates how sexual dysfunctions can affect each member of a couple.

349

CASE 11.6 • FROM THE OUTSIDE: Sexual Dysfunctions

Sarah had lost all interest in sex, but she was willing to be sexual for the sake of intimacy, which she still enjoyed. Her husband, Benjamin, however, had a hard time not taking it personally that she couldn’t have an orgasm, and began to fixate on the problem, bringing it up in and out of the bedroom. But all the time and effort he was spending on her arousal only made her more anxious and less likely to become aroused at all. He started to feel inadequate as a result and began to find it difficult to maintain his erection. They had gone on in this way for years, and now were close to a separation.

(Berman et al., 2001, p. 168)

In the following sections, we examine sexual dysfunctions.

Sexual Desire Disorders and Sexual Arousal Disorders

Sexual desire can be thought of as having three major components: (1) a neurological and other biological component (related to hormones and brain activity, which lead to a genital response); (2) a cognitive component (related to an inclination or desire to be sexual); and (3) an emotional and relational component (related to being willing to engage in sex with a particular person at a specific place and time) (Levine, 1988). Difficulty in any of these components can lead to a sexual desire disorder. However, a discrepancy in the level of desire between someone and his or her partner does not, in and of itself, constitute a disorder in sexual desire.

Sexual arousal disorders occur when a person persistently cannot become aroused or cannot maintain arousal during a sexual encounter. These disorders can arise when a person has difficulty progressing from desire to excitement. This difficulty can occur when any of the following persistently interfere: (1) when the pleasurable stimulation gets interrupted (e.g., when a couple stops their sexual behavior because their young child enters their bedroom), (2) when other external stimuli interfere (e.g., when a car alarm goes off outside), or (3) when internal stimuli interfere (e.g., when the person becomes anxious, afraid, sad, or angry or has thoughts that intrude) (Malatesta & Adams, 2001).

Like sexual desire, sexual arousal involves neurological and other biological components (responses to stimuli and stimulation), cognitive components (thoughts), and emotional components (Rosen & Beck, 1988). And any, or any combination, of these components can contribute to a problem. For example, a man can have an adequate erection but think that he is inadequate because he believes that his penis is not hard enough. Similarly, a woman may respond to the biological sensations of sexual arousal by being afraid of losing control (Malatesta & Adams, 2001).

Male Hypoactive Sexual Desire Disorder

Male hypoactive sexual desire disorder A sexual dysfunction characterized by a persistent or recurrent lack of erotic or sexual fantasies or an absence of desire for sexual activity.

As specified in DSM-5, one type of problem of desire is male hypoactive sexual desire disorder, the hallmark of which is a persistent or recurrent lack of erotic or sexual fantasies or an absence of desire for sexual activity (see TABLE 11.6). This lack of desire may or may not be lifelong, and it may occur in all situations (generalized) or only in particular situations (such as with a specific person), but it must cause distress. Hypoactive sexual desire focuses primarily on a man’s cognitive (fantasies) and emotional/relational (desire) state (Malatesta & Adams, 2001). Men with hypoactive sexual desire disorder may or may not still be willing to engage in sexual behavior with a partner.

However, a man who is depressed and, as part of the depression, has little or no sexual desire (a symptom of depression) is not considered to have hypoactive sexual desire disorder because the low desire is caused by another disorder.

350

Erectile Disorder

Erectile disorder A sexual dysfunction characterized by a man’s persistent difficulty obtaining or maintaining an adequate erection until the end of sexual activity, or a decrease in erectile rigidity; sometimes referred to as impotence.

Erectile disorder (impotence, in nontechnical language) is an arousal disorder characterized by a persistent difficulty obtaining or maintaining an adequate erection until the end of sexual activity, or a decrease in erectile rigidity (see TABLE 11.6; American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Some men with erectile disorder are able to have erections during foreplay but not during actual penetration. Others are not able to obtain a full erection with a new partner or in some situations; still others, such as Harry, in Case 11.7, have the problem during any type of sexual activity. If the man is able to have a full erection during masturbation, biological causes are unlikely. More than half of men over 40 years old have at least some problems in attaining or maintaining an erection (Feldman et al., 1994), and thus erectile disorder can be seen as a normal by-product of aging. It is estimated that 300 million men worldwide will develop erectile disorder by the year 2025, in part because of the increased aging of the population (cited in Shabsigh et al., 2003). However, psychological factors can contribute to erectile disorder; it is not always a neurological or other biological problem or a consequence of normal aging.

CASE 11.7 • FROM THE OUTSIDE: Erectile Disorder

Harry [had been married for 2 years when] he found out his wife had been involved in numerous extramarital affairs and divorced her. He said his friends all knew but were reluctant to tell him. Following the divorce he encountered erectile problems with all partners—even those to whom he felt close.

(Althof, 2000, p. 261)

Female Sexual Interest/Arousal Disorder

Female sexual interest/arousal disorder A sexual dysfunction characterized by a woman’s persistent or recurrent lack of or reduced sexual interest or arousal; formerly referred to as frigidity.

Women who have problems with sexual desire often also have problems with arousal, and hence DSM-5 groups these desire and arousal problems together in a single disorder: female sexual interest/arousal disorder (formerly known as frigidity), which is a persistent or recurrent lack of or reduced sexual interest or arousal.

Problems regarding interest or arousal may include no interest in any sexual activity, no erotic or sexual thoughts, hesitation either to respond to a partner’s sexual invitations or to initiate sexual activity, reduced or no pleasure during most sexual encounters, or a lack of physical arousal. Any three of these six symptoms (see TABLE 11.6) are necessary for this diagnosis. As with all other sexual dysfunctions, the diagnosis of sexual interest/arousal disorder requires that the problem causes distress or difficulties in relationships and does not arise exclusively from another psychological or medical disorder.

Laura seems to have such a lack of sexual desire—a lack of any interest in sexual relations with Mike—and it bothers her that she doesn’t feel desire. As women age, decreased interest in sex is normal and is probably related to women’s hormonal shift with menopause: Women who have gone through menopause tend to report diminished desire (Eplov et al., 2007). In fact, women who enter menopause abruptly and at an early age because of the surgical removal of their uterus and ovaries are more likely to report low sexual desire than are their same-age counterparts who have not yet entered menopause (Dennerstein et al., 2006). In addition, psychological and social factors account for a given woman’s distress about decreased desire, and women in different European countries report different levels of distress in response to decreased desire (Graziottin, 2007).

Orgasmic Disorders

An orgasmic disorder is diagnosed when a clinician determines that a man or woman has experienced normal excitement and adequate stimulation for orgasm in normal circumstances (based on the person’s age and other factors)—but fails to have an orgasm. If a man or woman cannot achieve orgasm with intercourse but can do so through other types of sexual stimulation, the person is not necessarily considered to have an orgasmic disorder. Moreover, if orgasmic problems arise as a side effect from medications (such as SSRIs), a diagnosis of an orgasmic disorder should not be made. Disorders in this category may have neurological (and other biological), cognitive, and emotional elements.

351

Female Orgasmic Disorder

Female orgasmic disorder A sexual dysfunction characterized by a woman’s normal sexual excitement not leading to orgasm or to her having diminished intensity of sensations of orgasm.

Female orgasmic disorder is diagnosed when a woman’s normal sexual excitement does not lead to orgasm or her orgasms are significantly less intense (see TABLE 11.6). Women who experience occasional difficulty achieving orgasm do not have this disorder; the problem with achieving orgasm must be persistent and must exceed what would be expected based on the woman’s age and sexual experience. Moreover, to be diagnosed with this disorder, the problem with orgasm should not be caused by inadequate sexual stimulation. If a woman experiences orgasm through clitoral stimulation but not through vaginal intercourse, a diagnosis would not be made; most women require clitoral stimulation to have an orgasm. As with all other sexual dysfunctions, female orgasmic disorder is diagnosed only if the problem concerning orgasm causes distress; many women who rarely or never have orgasms report being satisfied sexually (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Approximately 5–24% of women have female orgasmic disorder (Laumann et al., 1994; Spector & Carey, 1990).

Clinicians distinguish between two types of female orgasmic disorder: generalized and situational. If female orgasmic disorder is generalized, the woman does not have an orgasm in any circumstance. If female orgasmic disorder is situational, the woman may have an orgasm but only in certain circumstances, for example, when masturbating. Lola, described in Case 11.8, has the generalized type of female orgasmic disorder.

CASE 11.8 • FROM THE OUTSIDE: Female Orgasmic Disorder

Lola, a 25-year-old laboratory technician, has been married to a 32-year-old cabdriver for 5 years. The couple has a 2-year-old son, and the marriage appears harmonious.

The presenting complaint is Lola’s lifelong inability to experience orgasm. She has never achieved orgasm, although during sexual activity she has received what should have been sufficient stimulation. She has tried to masturbate, and on many occasions her husband has manually stimulated her patiently for lengthy periods of time. Although she does not reach climax, she is strongly attached to her husband, feels erotic pleasure during lovemaking, and lubricates copiously. According to both of them, the husband has no sexual difficulty.

Exploration of her thoughts as she nears orgasm reveals a vague sense of dread of some undefined disaster. More generally, she is anxious about losing control over her emotions, which she normally keeps closely in check.

(Spitzer et al., 2002, pp. 238–239)

Delayed Ejaculation

Delayed ejaculation A sexual dysfunction characterized by a man’s delay or absence of orgasm.

Delayed ejaculation is a delay or absence of ejaculation in males; TABLE 11.6 lists the specific criteria. Delayed ejaculation is different from female orgasmic disorder in several respects: (1) Delayed ejaculation typically involves problems ejaculating with a partner, even though the man can easily ejaculate during masturbation (Apfelbaum, 1989, 2000); (2) delayed ejaculation typically involves problems ejaculating only during vaginal intercourse (some men, however, cannot ever ejaculate); and (3) its prevalence (less than 10% of the general male population) is lower than that of female orgasmic disorder (Spector & Carey, 1990). There is no set definition of what constitutes a “delay,” and the diagnosis should be made only if the man experiences adequate sexual stimulation.

352

Premature (Early) Ejaculation

Premature (early) ejaculation A sexual dysfunction characterized by ejaculation that occurs within a minute of vaginal penetration and before the man wishes it, usually before, immediately during, or shortly after penetration.

A second type of orgasm-related problem for men is premature ejaculation, which is characterized by ejaculation that occurs within a minute of vaginal penetration and before the male wishes it (TABLE 11.6; American Psychiatric Association, 2013). Men with premature ejaculation report not feeling a sense of control over their ejaculation and thus become apprehensive about future sexual encounters. (According to DSM-5, a man with “early” ejaculation that occurs without vaginal intercourse—such as with oral sex or anal intercourse—could not be diagnosed with this disorder.)

Premature ejaculation is considered by some to be a couple’s problem, as with Mr. and Mrs. Albert in Case 11.9. That is, it is a problem only insofar as the couple prefers the man to ejaculate in a particular phase of his partner’s sexual response cycle: Some couples try to have both partners achieve orgasm at around the same time, but this is difficult with premature ejaculation. Other couples do not find early ejaculation a problem; the partner is sexually stimulated to orgasm in other ways after the man ejaculates (Malatesta & Adams, 2001).

CASE 11.9 • FROM THE OUTSIDE: Premature Ejaculation

Mr. and Ms. Albert are an attractive, gregarious couple, married for 15 years, who [are in] the midst of a crisis over their sexual problems. Mr. Albert, a successful restaurateur, is 38. Ms. Albert, who since marriage has devoted herself to child rearing and managing the home, is 35. She reports that throughout their marriage she has been extremely frustrated because sex has “always been hopeless for us.” She is now seriously considering leaving her husband.

The difficulty is the husband’s rapid ejaculation. Whenever any lovemaking is attempted, Mr. Albert becomes anxious, moves quickly toward intercourse, and reaches orgasm either immediately upon entering his wife’s vagina or within one or two strokes. He then feels humiliated and recognizes his wife’s dissatisfaction, and they both lapse into silent suffering. He has severe feelings of inadequacy and guilt, and she experiences a mixture of frustration and resentment toward his “ineptness and lack of concern.” Recently, they have developed a pattern of avoiding sex, which leaves them both frustrated, but which keeps overt hostility to a minimum…. [Mr. Albert’s] inability to control his ejaculation is a source of intense shame, and he finds himself unable to talk to his wife about his sexual “failures.” Ms. Albert is highly sexual and easily aroused in foreplay but has always felt that intercourse is the only “acceptable” way to reach orgasm.

In other areas of their marriage, including rearing of their two children, managing the family restaurant, and socializing with friends, the Alberts are highly compatible. Despite these strong points, however, they are near separation because of the tension produced by their mutual sexual disappointment.

(Spitzer et al., 2002, pp. 266–267)

Sexual Pain Disorder: Genito-Pelvic Pain/Penetration Disorder

Genito-pelvic pain/penetration disorder A sexual dysfunction in women characterized by pain, fear, or anxiety related to the vaginal penetration of intercourse.

Some women experience significant pain with sexual activity, particularly with sexual intercourse. A sexual dysfunction related to consistent pain associated with sexual intercourse for women is genito-pelvic pain/penetration disorder, which is characterized by pain, fear, or anxiety related to the vaginal penetration of intercourse (see TABLE 11.6). Vaginismus, recurrent or persistent involuntary spasms of the musculature of the outer third of the vagina that interfere with sexual intercourse, may occur with genito-pelvic pain/penetration disorder. These spasms may be so strong that it is impossible to insert the penis into the vagina, or at least not without significant discomfort.

Up to 10–20% of women report recurrent pain with intercourse, though not necessarily to the degree required for a diagnosis of genito-pelvic pain/penetration disorder (American Psychiatric Association, 2013; Laumann et al., 1999; Rosen et al., 1993). When the pain persists, it can lead to problems with desire or excitement. This disorder is not diagnosed if the problem is caused exclusively by a lack of lubrication. Lynn in Case 11.10 has genito-pelvic pain/penetration disorder. TABLE 11.7 provides more information about the sexual dysfunctions.

| Prevalence |

|

| Comorbidity |

|

| Onset |

|

| Course |

|

| Gender Differences |

|

| Cultural Differences |

|

| Source: Unless otherwise noted, the source for the table material is American Psychiatric Association, 2013. |

353

CASE 11.10 • FROM THE INSIDE: Genito-Pelvic Pain/Penetration Disorder

Lynn talks about her experience with symptoms of genito-pelvic pain/penetration disorder.

We’ve been married for nine years and have two great kids. Unfortunately, family responsibilities and high stress jobs really cut into our together time. Exhaustion makes sex seem like an extra chore—just one more thing to do that we don’t have time to enjoy and now can’t. I don’t know if it’s from the busy, stressful lifestyle or not, or from being “out of practice,” but about a year ago intercourse began to really hurt. It started with a burning sensation some of the time during sex. I found myself getting more anxious that it would hurt again and it usually did. Trips to the doctor revealed little besides the standard “do more foreplay or use more lubricant” advice. Now it seems like my body just “tightens up” and we can hardly have sex at all. Entry is painful and besides burning I feel tightness, spasms, discomfort and anxiety. The pleasure is gone, and there is only the expectation of discomfort and frustration. Our marriage is suffering and it feels like a deep chasm is growing between us as sex has become impossible. My husband and I fight a lot more and I know he is growing impatient. I don’t want my children to be another statistic of divorce because of this. I just don’t know what to do.

(Vaginismus.com, 2007)

354

Criticisms of the Sexual Dysfunctions in DSM-5

Criticisms of the DSM-5 classification of and criteria for sexual dysfunctions focus on many issues, some of which carry over from the previous edition of DSM (Balon, 2008). In what follows we briefly consider three of these issues:

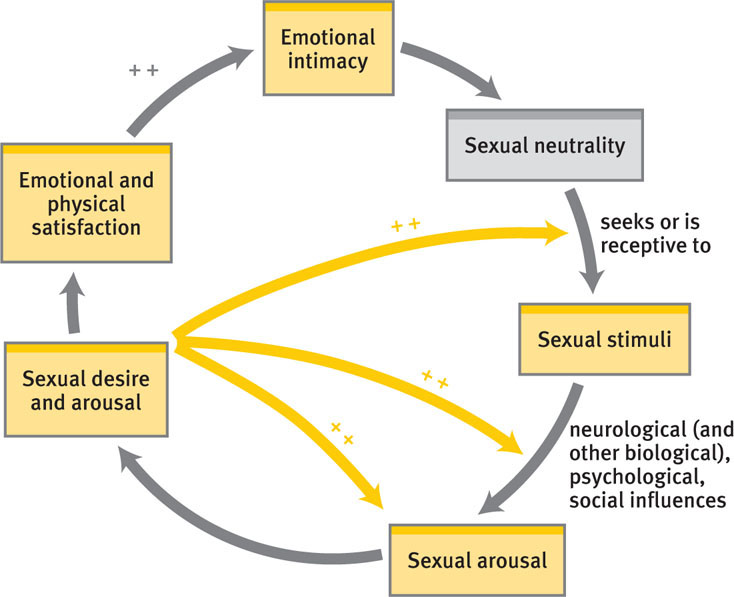

- The sexual dysfunctions are implicitly based on the progression in Masters and Johnson’s model of the sexual response cycle. However, this may not be the best model for understanding sexual dysfunctions in women. As illustrated in the alternative female sexual response cycle (Figure 11.3), emotional and physical satisfaction may include orgasm but not all women need to have an orgasm to feel satisfied.

FIGURE 11.3 • An Alternative Female Sexual Response Cycle An alternative model of the female sexual response cycle (Basson, 2001)—in the context of relationships—is analogous to a circle. The cycle starts with sexual neutrality: not feeling very sexual, but with an openness to seek or be receptive to sexual stimuli. In turn, such sexual stimuli may, depending on neurological (and other biological), psychological, and social factors operating at that moment, lead to sexual arousal, which in turn leads to a sense of desire and further arousal. The desire creates positive feedback loops (++) that lead to heightened arousal, which then leads to emotional and physical satisfaction. This satisfaction in turn produces a sense of emotional intimacy with her partner, making her more likely to be receptive to or seek out sexual stimuli in the future. She may also feel spontaneous sexual desire, which leads to positive feedback loops among the first three phases. Orgasm is not necessary for satisfaction.Source: Adapted from Basson, 2001.

FIGURE 11.3 • An Alternative Female Sexual Response Cycle An alternative model of the female sexual response cycle (Basson, 2001)—in the context of relationships—is analogous to a circle. The cycle starts with sexual neutrality: not feeling very sexual, but with an openness to seek or be receptive to sexual stimuli. In turn, such sexual stimuli may, depending on neurological (and other biological), psychological, and social factors operating at that moment, lead to sexual arousal, which in turn leads to a sense of desire and further arousal. The desire creates positive feedback loops (++) that lead to heightened arousal, which then leads to emotional and physical satisfaction. This satisfaction in turn produces a sense of emotional intimacy with her partner, making her more likely to be receptive to or seek out sexual stimuli in the future. She may also feel spontaneous sexual desire, which leads to positive feedback loops among the first three phases. Orgasm is not necessary for satisfaction.Source: Adapted from Basson, 2001. - The emphasis is on orgasm—in both men and women—as the conclusion of sexual activity (Tiefer, 1991). Sexual activity that does not end in orgasm is implicitly considered not satisfying (Kleinplatz, 2001).

- The DSM-5 criteria rest on a cultural definition of “normal” to define abnormal sexual functioning (Moynihan, 2003). Critics note that the norm promoted by American culture is that of an adolescent male, ever ready for sexual encounters and able to have erections on demand (Kleinplatz, 2001). As women and men age, they are more likely to meet the criteria for a sexual dysfunction even when there is no real “dysfunction”—only the body’s growing older (Tiefer, 1987, 1991).

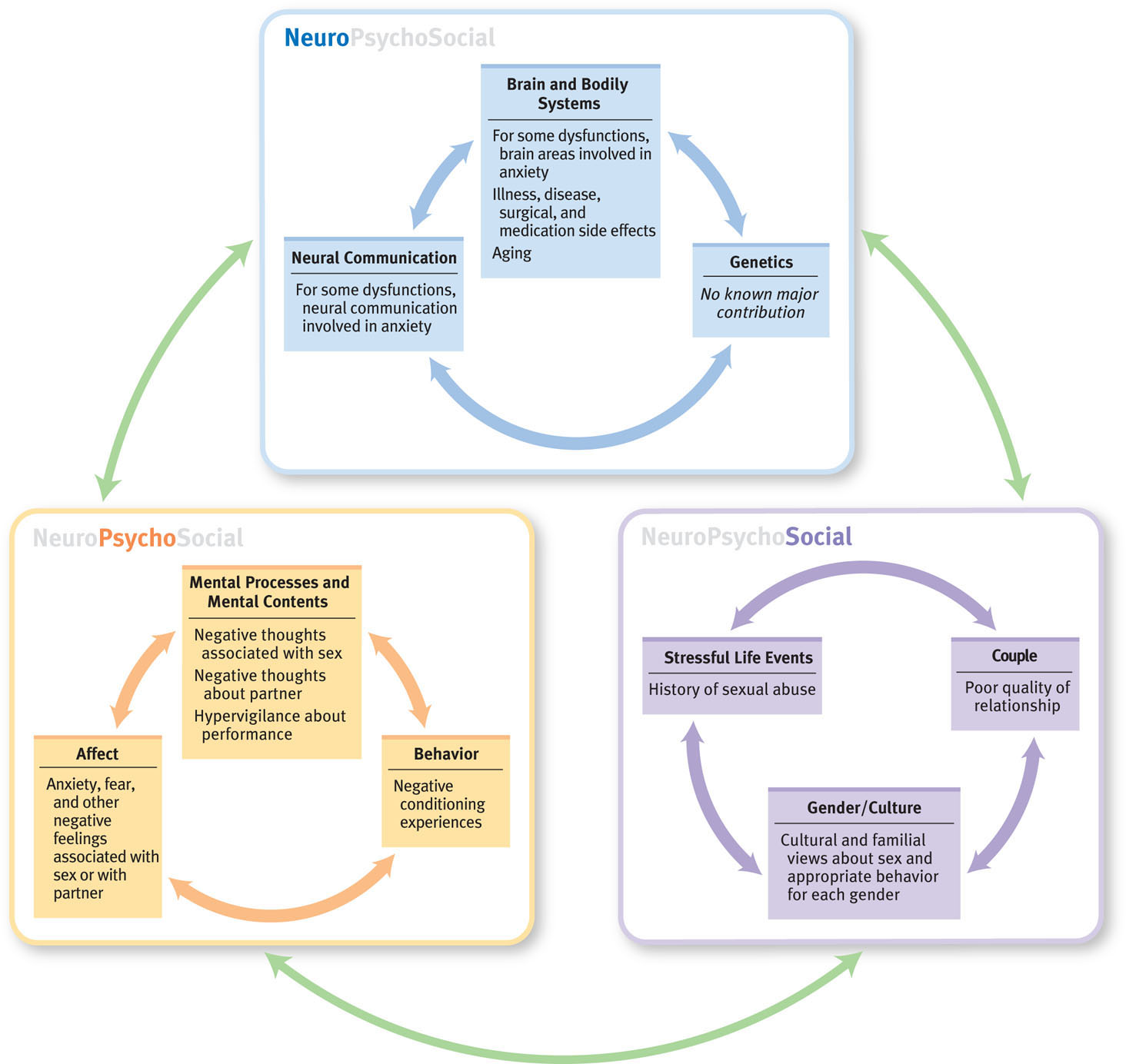

Understanding Sexual Dysfunctions

We can view Laura’s lack of sexual desire as being related, at least in part, to Mike’s sexual difficulties: As Mike became more distant, Laura’s desire for sexual intimacy with Mike waned. Their experiences highlight the fact that sexuality and any problems related to it develop through feedback loops among neurological (and other biological), psychological, and social factors.

Neurological and Other Biological Factors

In this section, we first consider how disease, illness, surgery, and medication can, directly and indirectly, disrupt normal sexuality. We then turn to the effects of normal aging, which can produce sexual difficulties.

Sexual Side Effects: Disease, Illness, Surgery, and Medication

Disease or illness can produce sexual dysfunction directly, as occurs with prostate or cervical cancer, and indirectly, as occurs with diabetes or circulation problems that limit blood flow to genital areas. In addition, surgery can lead to sexual problems: Half of women who survive major surgeries for gynecological-related cancer develop sexual difficulties that do not improve over time (Andersen et al., 1989).

355

Some medications can interfere with normal sexual response, including:

- SSRIs and dopamine-blocking medications such as traditional antipsychotics,

- beta-blockers and other medications that treat high blood pressure,

- anti-seizure medication,

- estrogen and progesterone medications,

- HIV medications, and

- narcotics and sedative-hypnotics.

Alcohol can also disrupt the normal sexual response cycle.

Aging

Researchers have found that normal aging can affect sexual functioning among older people (George & Weiler, 1981). For instance, older women often produce less vaginal lubrication after menopause; when this dryness is not addressed (for instance, with an over-the-counter lubricant such as Astroglide or K-Y Jelly), the dryness can cause intercourse to be painful and lead to genito-pelvic pain/penetration disorder.

In addition, as men age, their testosterone levels decrease significantly, which may lead them to require prolonged tactile stimulation before they can attain an erection. Older men are likely to experience reduced penile hardness, decreased urgency to reach orgasm, and a longer refractory period (Butler & Lewis, 2002; Masters & Johnson, 1966).

In addition to the normal biological changes that arise with age, older people of both sexes may develop illnesses or diseases that make sexual activity physically more challenging. They also may take medications that have side effects that interfere with their sexual response. However, most older people report that they continue to enjoy sex.

Psychological Factors in Sexual Dysfunctions

Certain beliefs and experiences can predispose people to develop sexual dysfunctions (see TABLE 11.8). In addition, a woman may believe that women in general lose their sexual desire as they age, and a man may believe that “real men” have intercourse at least twice a day and that only rock-hard erections will satisfy women (Nobre & Pinto-Gouveia, 2006). Such beliefs can lead to a self-fulfilling prophecy if they produce the perception of a dysfunction and that perception in turn leads to a real dysfunction. For example, a man who believes that women are only satisfied by very hard erections may develop a problem as he ages: He may notice that his erections are not as hard as they were when he was younger and then become self-conscious and preoccupied during sex, which does in fact lead him to fail to satisfy his partner.

| Event | Effect |

|---|---|

| The view that sex is dirty and sinful | Early learning of such negative attitudes toward sex and misinformation leads to fears and inhibitions, which can lead to problems of desire, arousal, orgasm, and pain. |

| Early negative conditioning experiences | In men, premature ejaculation can develop after hurrying to have an orgasm quickly for fear of being “caught.” In women, a fear of pregnancy or being “caught” can lead to anxiety that contributes to sexual dysfunction. |

| Sexual trauma | Sexual trauma can produce negative conditioning and can lead to a fear of sex, as well as arousal and desire problems. |

| Sources: Bartoi & Kinder, 1998; Becker & Kaplan, 1991; Kaplan, 1981; Laumann et al., 1999; LoPiccolo & Friedman, 1988; Masters & Johnson, 1970; Silverstein, 1989. | |

Having been sexually abused as a child also predisposes a person to develop sexual dysfunctions. Consider the fact that male victims of childhood sexual abuse are three times more likely to have problems with their erections and twice as likely to have problems of desire and premature ejaculation as their peers who did not experience childhood sexual abuse (Laumann et al., 1999). Similarly, women who were victims of childhood sexual abuse are more likely than women who were not abused to report sexual problems (although not necessarily problems that meet the DSM-5 criteria for sexual dysfunctions; Staples et al., 2012).

356

Psychological factors that precipitate, or trigger, sexual dysfunctions generally involve the following sorts of preoccupations:

- focusing attention on sex-related fears and worries, which distract and detract during a sexual encounter;

- feeling uncomfortable with how one’s body may look or feel to a partner (Berman & Berman, 2001); and

- worrying about nonsexual matters, such as work or family problems.

Once someone has a problem with desire, arousal, orgasm, or pain, he or she may become anxious that it will happen again, which sets up a self-fulfilling prophecy and becomes a maintaining factor. For instance, when a single sexual experience was perceived as a “failure,” a person may become anxious during subsequent sexual experiences, monitoring his or her responsiveness (and so thinking about the sexual response rather than experiencing it)—which in turn can interfere with a normal sexual response and create a sexual dysfunction (Bach et al., 1999; Quinta Gomes & Nobre, 2012).

Social Factors

© Alex Mares-Manton/AGE Fotostock

Although sexuality involves how we see ourselves, it usually also involves other people. (Woody Allen once said that his favorite part of masturbation was the cuddling afterwards. Think about why this is funny.) The sexual relations of a couple are influenced by how the partners relate to each other, specifically: (1) how they express and resolve a conflict, (2) how they communicate their needs and desires, their likes and dislikes, (3) how they handle stress, and (4) how strongly attracted they each are to each other (Tiefer, 2001). For women in particular, satisfaction with their relationship plays a big part in sexual desire, arousal, and orgasm (Burri et al., in press). For example, Mike’s sexual secret led him to pull away from Laura sexually, which led her to think that he wasn’t interested in sex. From her vantage point, he appeared to have a sexual desire problem, and she herself then lost interest.

Feedback Loops in Understanding Sexual Dysfunctions

Just as neurological, psychological, and social factors influence each other and contribute to a normal sexual response, feedback loops among these factors can contribute to sexual dysfunctions (see Figure 11.4). Such feedback loops best explain why some people, and not others, develop sexual dysfunctions. For instance, people’s sexual beliefs (“I won’t be able to have an orgasm”; psychological factor) can influence other factors: The beliefs create fears and anxieties that can lead to high levels of sympathetic nervous system activity (neurological factor), which then interfere with sexual arousal and orgasm (Apfelbaum, 2001; Kaplan, 1981; Masters & Johnson, 1970). Current problems in a relationship (social factor) similarly affect sexual functioning, as can having been sexually abused (Bartoi & Kinder, 1998; DiLillo, 2001; Laumann et al., 1999). And the influences also run in the opposite direction: If the body does not respond appropriately, this will affect not only a person’s beliefs but also his or her relationships.

357

Kevin Mazur/WireImage for MTV/Getty Images

Familial and cultural views of sexuality (social factors) can also influence sexual functioning: We are all taught about sexuality both directly (what our parents, teachers, religious leaders, and peers tell us) and indirectly (through observations of family members or friends and from television, movies, books, and the Internet). Some people are taught that sexual relations outside of marriage are wrong, whereas other people are taught that sexual experimentation before marriage is a good thing. Such direct and indirect lessons help shape each person’s concepts of appropriate or normal sexuality. Depending on what a person learns about sex, he or she may be primed to have sexual difficulties in some situations.

Thus, neurological, psychological, and social factors influence each other in ways that predispose some people to develop a sexual dysfunction, and that precipitate and maintain it once it develops.

358

Treating Sexual Dysfunctions

After the specific nature of a sexual problem has been determined, treatment can target the relevant factors. Patients may see a sex therapist, usually a mental health clinician who has been trained to assess and treat problems related to sexuality and sexual dysfunction. Depending on the nature of the problem and the types of treatments the patient—and his or her partner—are interested in, treatment may include medication, cognitive-behavioral therapy, sex therapy (which may provide specific guidance and techniques to treat sexual problems), couples therapy, or some other type of therapy (Moser & Devereux, 2012).

Targeting Neurological and Other Biological Factors: Medications

There has been an increasing trend toward the medicalization of sex therapy, a tendency to target neurological and other biological factors (see TABLE 11.9) and pay less attention to psychological and social factors. In the 1990s, medical treatments for erectile dysfunction began in earnest, with the advent of the drug Viagra and the marketing campaign for it, which brought the topic of erectile dysfunction from a rarely discussed but relatively common problem among older men to a topic of everyday conversation. Viagra (sildenafil citrate) is one of the class of drugs called phosphodiesterase type 5 inhibitors, or PDE-5 inhibitors. Viagra doesn’t cause an erection directly; instead, the drug operates by increasing the flow of blood to the penis only when a man is sexually excited. Viagra (and its competitors, such as Cialis) is not a cure but a treatment for erectile dysfunction, and it is effective only if the man takes a pill before sexual activity.

| Sexual phase | Female | Male |

|---|---|---|

| Desire | Female sexual arousal disorder: PDE-5 inhibitors when arousal problems have a medical cause. Wellbutrin (bupropion) may counteract diminished desire that is a side effect of SSRIs taken for another disorder | Male hypoactive sexual desire disorder: Testosterone pills or cream. |

| Arousal | Erectile disorder: PDE-5 inhibitors | |

| Orgasm | Female orgasmic disorder: (Medications have not reliably proved effective in studies that include a placebo group.) |

Delayed ejaculation: (Medications have not reliably proved effective in studies that include a placebo group.) Premature ejaculation: SSRIs |

| Pain | Genito-pelvic pain/penetration disorder: Estrogen cream for menopause related dryness; anti-anxiety medication for anticipatory anxiety about penetration. |

359

Some women with arousal disorders use PDE-5 inhibitors because these medications can have an analogous effect on the clitoris. However, PDE-5 inhibitors are most effective with women who—for medical reasons—have reduced blood flow to the clitoral area, which leads to decreased physical arousal (Berman et al., 2001). Critics point out that prescribing this type of medication for a woman will not improve sexual functioning when the problem is with her relationship, not her anatomy (Bancroft, 2002).

Targeting Psychological Factors: Shifting Thoughts, Learning Behaviors

Sensate focus exercises A behavioral technique that is assigned as homework in sex therapy, in which a person or couple seeks to increase awareness of pleasurable sensations that do not involve genital touching, intercourse, or orgasm.

Two types of treatments directly target psychological factors: Sex therapy and psychological therapies—such as CBT or psychodynamic therapy—that address feelings and thoughts about oneself and others and how they may relate to sexual problems.

One of the goals of treatments that directly target psychological factors related to sexual dysfunctions is to educate patients about sexuality and the human sexual response. Another goal is to help patients develop strategies to counter negative thoughts, beliefs, or attitudes that may interfere with sexual desire, arousal, or orgasm (Carey & Gordon, 1995). For instance, during sexual activity, some people are preoccupied with nonsexual thoughts that prevent them from reaching full arousal or orgasm. These nonsexual thoughts might be work-related worries, thoughts about household tasks that need to be done, or being alert for someone who would interrupt the sexual encounter. Cognitive treatment may involve teaching a patient how to filter out such thoughts and (re)focus on the sexual interaction. The therapist might teach the patient to apply standard cognitive methods to sexual encounters, such as problem solving (“You could turn the phone off”) or cognitive restructuring (“Are you likely to think of a solution to your work problem while making love? If not, you can let your mind focus on the physical sensations you are experiencing”).

GETTING THE PICTURE

© Shades of Naughty/Alamy

In addition to addressing very specific sex-related thoughts and feelings, the treatment may also address the patient’s view of himself or herself. Sometimes the sense of being dysfunctional or inadequate generalizes from the sexual realm to the whole self, and the person with a sexual dysfunction comes to have low self-esteem and self-doubts generally. In such cases, the therapy may use cognitive and behavioral methods to address such dysfunctional thoughts and feelings.

Treatment that relies on CBT typically involves “homework.” Depending on the nature of the problem, the homework may be completed by the patient or by the patient and his or her partner together. Homework for women with female orgasmic disorder (as well as other sexual dysfunctions) may include masturbation in order to learn more about which sensations and fantasies facilitate arousal and orgasm (Meston et al., 2004). For many patients, a first step is to begin to (re)discover pleasurable sensations through specific homework exercises. At the beginning of behavioral treatment, homework may include sensate focus exercises, which increase awareness of pleasurable sensations while prohibiting genital touching, intercourse, or orgasm; rather, partners take turns touching other parts of each other’s bodies so that each can discover what kinds of stimulation feel most enjoyable (Baucom et al., 1998; LoPiccolo & Stock, 1986).

360

The goals of behavioral techniques are to help patients develop a more relaxed awareness of their bodies and increase their orgasmic responses and control. Treatment may also involve a realistic look at a person’s or couple’s daily work schedule, followed by a discussion of how to have sexual encounters during which the partners are not too tired or distracted.

Targeting Social Factors: Couples Therapy

The sex therapy techniques discussed in the previous section may be implemented alone (by the person with a sexual dysfunction) or with a partner. Sex therapy may involve teaching couples specific cognitive and behavioral techniques. However, implementing such techniques with a partner requires motivation and willingness to be open with the partner about sexual matters and to experiment sexually. Moreover, how a couple interacts sexually occurs against the backdrop of their overall relationship. Treatment may focus on the issues in the couple’s relationship (couples therapy, rather than sex therapy per se) and include teaching communication, intimacy, and relationship skills (Baucom et al., 1998; Beck, 1995; Heiman, 2002b); such skills include assertiveness, problem solving, negotiation, and conflict management. Couples therapy may also address issues of power, control, and lifestyle as they relate to the sexual dysfunction; for example, the therapist may employ techniques from systems therapy to focus on assertiveness within the sexual aspects of the relationship. Treatment for a partner’s sexual dysfunction in a lesbian or gay couple may also address special issues that affect their sexual relationship, such as living “in the closet” or sexual intimacy when one partner is HIV positive (Nichols, 2000).

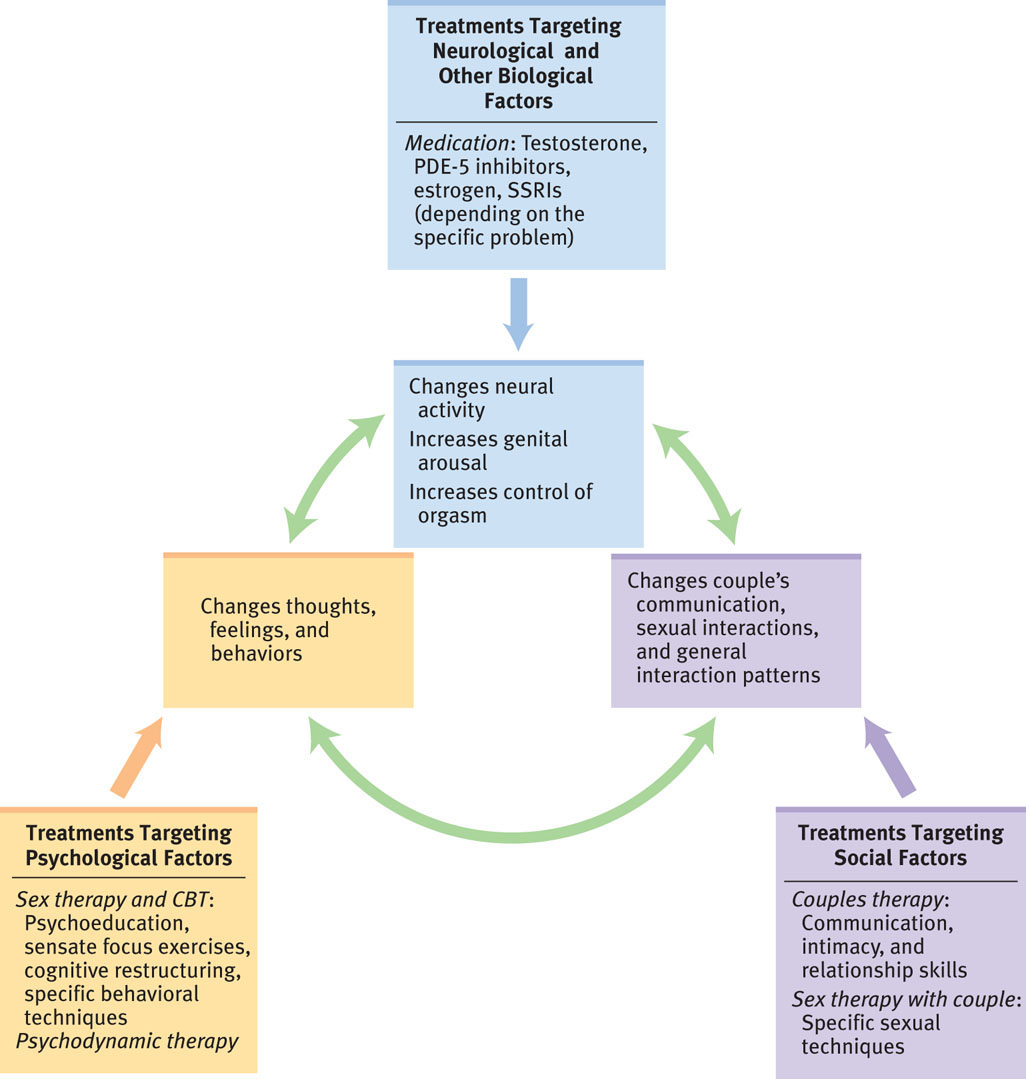

Feedback Loops in Treating Sexual Dysfunctions

Like successful treatment for any other psychological disorder, successful treatment of sexual dysfunctions ultimately affects all the neuropsychosocial factors (see Figure 11.5). For instance, CBT for female orgasmic disorder targets psychological factors (the thoughts, beliefs, and feelings related to sex or orgasm and behaviors such as masturbation) (Frühauf et al., in press; Heiman, 2002a). In turn, changes in psychological factors lead, through feedback loops, to changes in neurological and other biological factors (which underlie arousal and orgasm) as well as social factors (the meaning for both partners of a sexual interaction or an orgasm and the changes in their relationship). A similar set of feedback loops occurs with CBT for genito-pelvic pain/penetration disorder (ter Kuile et al., 2007): CBT changes thoughts and feelings about penetration, which in turn changes the responses of the vaginal muscles, making vaginal intercourse with a partner possible—which then affects the nature of the relationship.

361

Although all the techniques mentioned may alleviate sexual dysfunctions, the definition of “success” is less clear-cut than for treatments of most other psychological disorders. As we noted at the beginning of this chapter, sexuality and sexual dysfunctions typically involve other people, and a treatment that the patient views as successful may not be perceived that way by the partner. Consider an older man whose erectile dysfunction was treated with Viagra. He may have been pleased by his response to the drug treatment, only to discover that his wife was now unhappy about his sustained erections and more frequent desire for intercourse (Althof et al., 2006). She, then, might be diagnosed with a sexual desire problem. However, she might explain that when her husband had difficulty with his erections, he was much more affectionate, sexually attentive to her, and creative in their sexual interactions. Now he is goal-directed, focusing almost exclusively on intercourse; solving his erectile dysfunction led to changes in the couple’s sexual relations that were not viewed as positive by his wife. Treatments—such as medication—that directly target only one type of factor may seem to resolve the problem for the patient but instead can (via feedback loops among the three types of factors) have unexpected negative consequences for the couple.

362

Thinking Like A Clinician

Chi-Ling and Yinong were in their 30s and had been trying to have a baby for a year. Their sexual relations were strained: They had sex when the ovulation predictor test kit indicated that they should, and each month’s attempt and subsequent failure made them anxious. There was no joy or love in their sexual relations, and most of the time Chi-Ling was barely aroused and lubricated; she rarely had orgasms anymore. She just wanted Yinong to hurry up and ejaculate, and he was finding it increasingly difficult to do so. Based on what you have read, do you think that Chi-Ling or Yinong has a sexual dysfunction, and if so, which one(s)? Support your position. If you could obtain additional information before you decide, what would you want to know, and why?