12.2 Understanding Schizophrenia

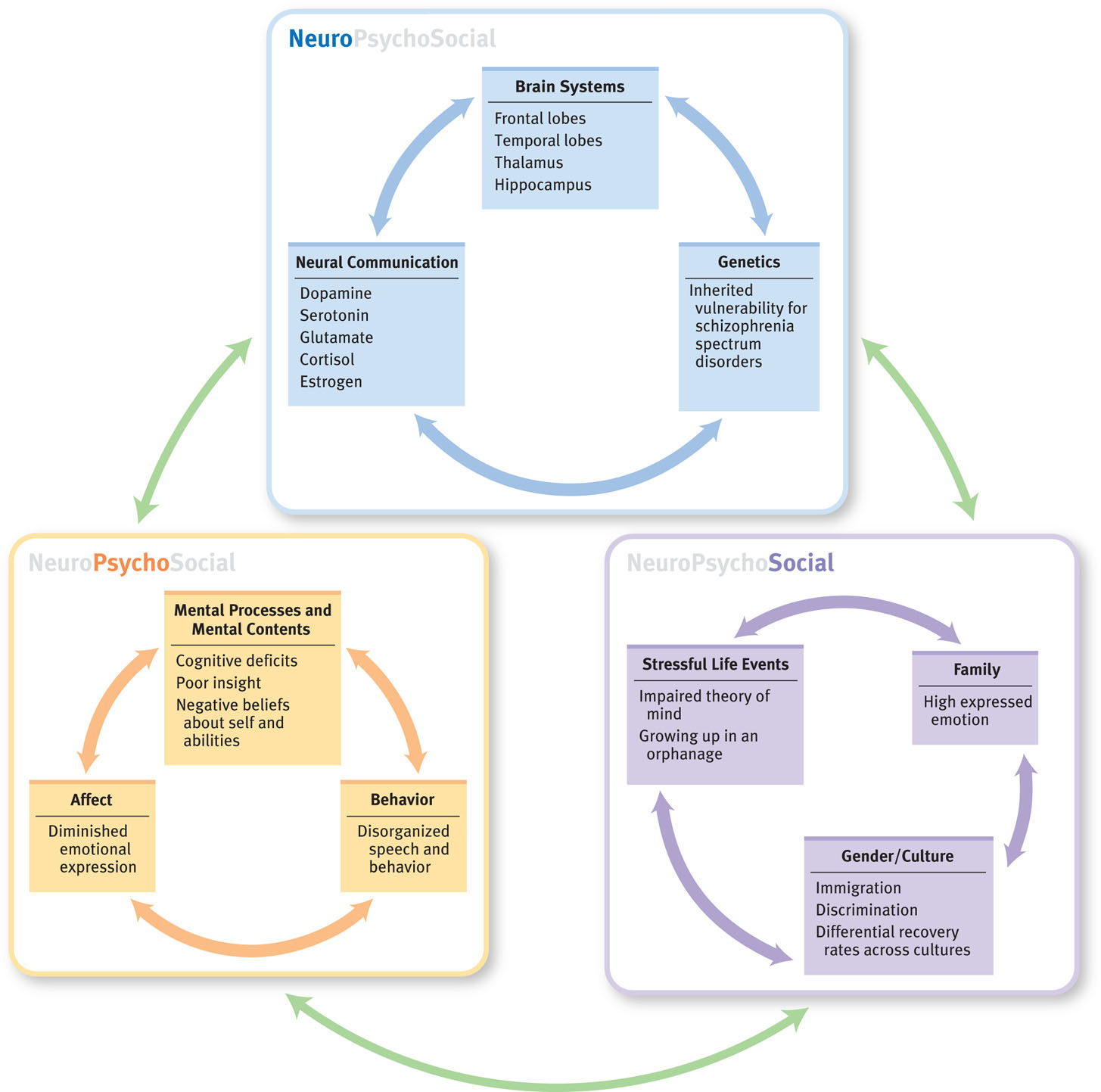

Despite the low odds that all four of the Genain quads would develop schizophrenia, it did happen. Why? The neuropsychosocial approach helps us to understand the factors that lead to schizophrenia and how these factors influence each other. As we shall see, although neurological factors (including genes) can make a person vulnerable to the disorder, psychological and social factors also play key roles—which may help explain not only why all four Genain quads ended up with schizophrenia but also why the disorder affected them differently.

The quads shared virtually all the same genes, looked alike, and, at least in their early years, were generally treated similarly, especially by Mrs. Genain. However, Hester was smaller and frailer than the others; she weighed only 3 pounds at birth and could not always keep up with her sisters. Because of Hester’s difficulties, it wasn’t always possible to treat the four girls the same, and so Mr. and Mrs. Genain sometimes treated them as two pairs of twins: Nora and Myra were paired together (they were seen as most competent), and Iris—who in fact was almost as competent as Nora and Myra—was paired with Hester.

In the following we will examine the specific neurological, psychological, and social factors that give rise to schizophrenia and then examine how these factors affect one another.

Neurological Factors in Schizophrenia

Perhaps more than for any other psychological disorder, neurological factors play a crucial role in the development of schizophrenia. These factors involve brain systems, neural communication, and genetics.

Brain Systems

People who have schizophrenia have abnormalities in the structure and function of their brains. The most striking example of a structural abnormality in the brains of people with schizophrenia is enlarged ventricles, which are cavities in the center of the brain that are filled with cerebrospinal fluid (Vita et al., 2006). Larger ventricles means that the size of the brain itself is reduced. Thus, people who later develop schizophrenia have brains that are smaller than normal even before they develop the disorder. This occurs, in part, because their brains never grew to “full” size. In addition, research suggests that schizophrenia causes parts of the brain to shrink (DeLisi et al., 1997; Gur et al., 1997; Rapoport et al., 1999).

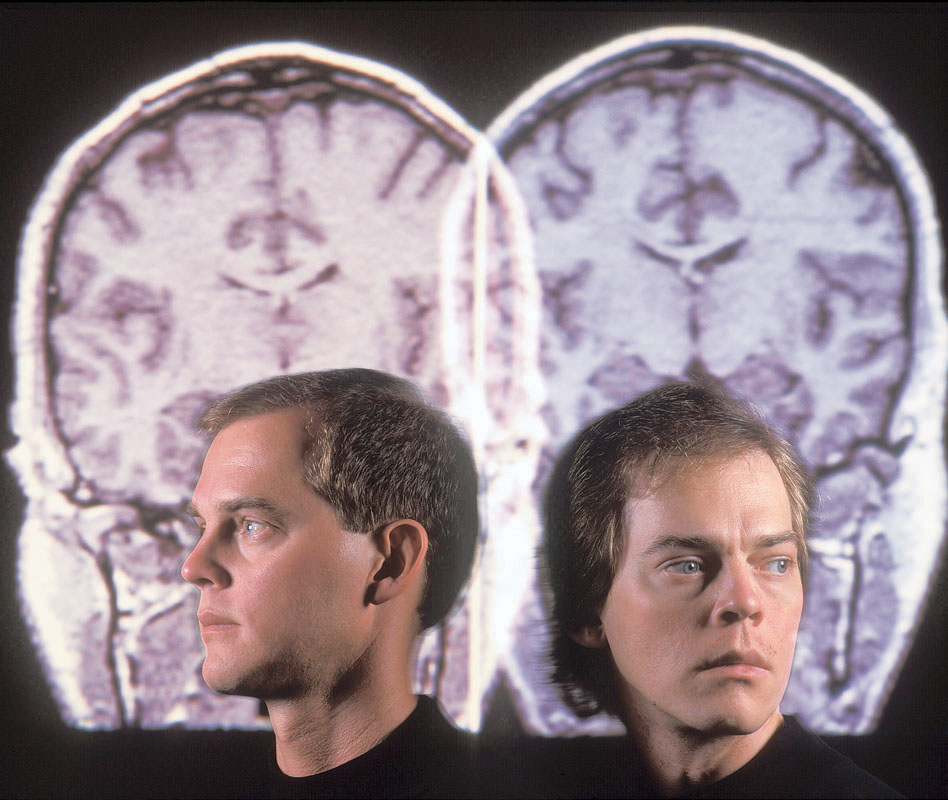

In 1981, the Genain sisters, then 51 years old, returned to NIMH for a 3-month evaluation; during that time, they were taken off their medications. CT scans of the quads showed similar brain abnormalities in all four sisters (Mirsky & Quinn, 1988). However, even though they were basically genetically identical, their performance on neuropsychological tests varied: Nora and Hester showed more evidence of neurological difficulties, and they were more impaired in their daily functioning when not taking medication. Thus, once again, we see that genes are not destiny and that brain function cannot be considered in isolation. The brain is a mechanism, but how it performs depends in part on how it is “programmed” by learning and experience—which are psychological factors.

In the following sections, we consider the likely role of specific brain abnormalities and possible causes of such abnormalities, and then we examine telltale neurological, bodily, or behavioral signs that may indirectly reveal that a person is vulnerable to developing the disorder.

381

A Frontal Lobe Defect?

Based on the specific cognitive deficits exhibited by people with schizophrenia, many researchers have hypothesized that such people have impaired frontal lobe functioning. The root of this impairment may lie in the fact that the human brain has too many connections among neurons at birth, and part of normal maturation is the elimination, or pruning, of unneeded connections (Huttenlocher, 2002). Research results suggest that an excess of such pruning takes place during adolescence for people who develop schizophrenia: Too many of the neural connections in the frontal lobes are eliminated, which may account for some of the neurocognitive deficits that typically accompany this disorder (Pantelis et al., 2003; Walker et al., 2004).

Impaired Temporal Lobe and Thalamus?

Enlarged ventricles are associated with decreased size of the temporal lobes. This is significant for people with schizophrenia because the temporal lobes process auditory information, some aspects of language, and visual recognition (Levitan et al., 1999; Sanfilipo et al., 2002). Abnormal functioning of the temporal lobes may underlie some positive symptoms, notably auditory hallucinations, in people with schizophrenia. The thalamus, which transmits sensory information to other parts of the brain, also appears to be smaller and to function abnormally in people with schizophrenia (Andrews et al., 2006; Guller et al., 2012). Abnormal functioning of the thalamus is associated with difficulties in focusing attention, in distinguishing relevant from irrelevant stimuli, and in particular types of memory difficulties, all of which are cognitive deficits that can arise with schizophrenia.

Abnormal Hippocampus?

The hippocampus—a subcortical brain structure crucially involved in storing new information in memory—is smaller in people with schizophrenia and their first-degree relatives (parents and siblings) than in control participants (Seidman et al., 2002; Vita et al., 2006). This abnormal characteristic may contribute to the deficits in memory experienced by people with schizophrenia (Olson et al., 2006; Yoon et al., 2008).

Interactions Among Brain Areas

Some researchers propose that schizophrenia arises from disrupted interactions among the frontal lobes, the thalamus, and the cerebellum—which may act as a timekeeper, synchronizing and coordinating signals from many brain areas (Andreasen, 2001; Andreasen et al., 1999). According to this theory, the thalamus fails to screen out sensory information, which overwhelms subsequent processing—and thus the form and content of the person’s thoughts become confused.

Possible Causes of Brain Abnormalities

How might these brain abnormalities arise? Researchers have identified several possible causes, some of which could affect the developing brain of a fetus or a newborn:

- maternal malnourishment during pregnancy, particularly during the first trimester (Brown, van Os, et al., 1999; Wahlbeck et al., 2001).

- maternal illness during the 6th month of pregnancy. During fetal development, neurons travel to their final destination in the brain and establish connections with other neurons (in a process called cell migration). If the mother catches the flu or another viral infection in the second trimester, this may disrupt cell migration in the developing fetus’s brain, which causes some neurons to fall short of their intended destinations. Because the neurons are not properly positioned, they form different connections than they would have formed if they had been in the correct locations—leading to abnormal neural communication (Brown, Begg, et al., 2004; Green, 2001; McGlashan & Hoffman, 2000). In general, an immune challenge to the developing fetus in turn can affect brain development (Meyer, 2013; Watanabe et al., 2010).

- oxygen deprivation, which can arise from prenatal or birth-related medical complications (McNeil et al., 2000; Zornberg et al., 2000). Studies have shown that people with schizophrenia who did not receive enough oxygen at specific periods before birth have smaller hippocampi than do people with schizophrenia who were not deprived of oxygen during or before birth (van Erp et al., 2002)—which may be related to memory problems.

382

Biological Markers

Biological marker A neurological, bodily, or behavioral characteristic that distinguishes people with a psychological disorder (or a first-degree relative with the disorder) from those without the disorder.

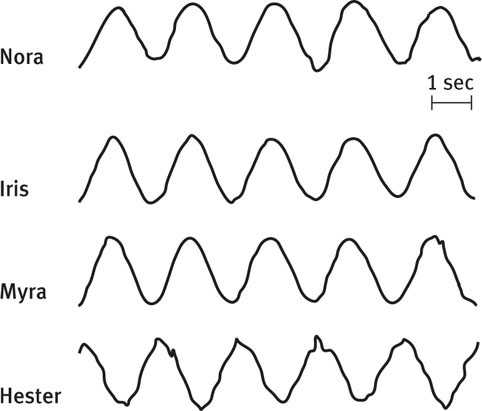

When a neurological, bodily, or behavioral characteristic distinguishes people with a psychological disorder (or people with a first-degree relative with the disorder) from people who do not have the disorder, it is said to be a biological marker for the disorder. One biological marker for schizophrenia, but not other non-psychotic psychological disorders, is difficulty maintaining smooth, continuous eye movements when tracking a light as it moves across the visual field; such tracking is called smooth pursuit eye movements (Holzman et al., 1984; Iacono et al., 1992). This difficulty reflects underlying neurological factors and is associated with irregularities in brain activation while people visually track moving objects (Hong et al., 2005). Although it is not clear exactly why people with schizophrenia and their family members have this specific difficulty, researchers believe that it can help to identify people who are at risk to develop schizophrenia. Figure 12.2 shows the results of smooth pursuit eye movement recordings for the Genain sisters.

Another biological marker for schizophrenia is sensory gating (Freedman et al., 1996), which is assessed as follows: Participants hear two clicks, one immediately after the other. Normally, the brain responds less strongly to the second click than to the first. However, people with schizophrenia and their first-degree relatives don’t show the normal large drop in the brain’s response to the second click. This has been interpreted as a manifestation of the difficulties that people with schizophrenia can have in filtering out unimportant stimuli.

A third type of biological marker for schizophrenia has been reported by researchers who performed careful analyses of home movies of children who were later diagnosed with schizophrenia (Grimes & Walker, 1994; Walker et al., 1993). They found that children who went on to develop schizophrenia were different from their siblings: They made more involuntary movements, such as writhing or excessive movements of the tongue, lips, or arms. This tendency for involuntary movement was particularly evident from birth to age 2 but could be seen even through adolescence in people who later developed the disorder (Walker et al., 1994). Moreover, those who displayed more severe movements of this type later developed more severe symptoms of schizophrenia (Neumann & Walker, 1996).

383

Neural Communication

Schizophrenia is likely to involve a complex interplay of many brain systems, neurotransmitters, and hormones.

Dopamine

One neurotransmitter that is clearly involved in schizophrenia is dopamine. The dopamine hypothesis proposes that an overproduction of dopamine or an increase in the number or sensitivity of dopamine receptors is responsible for schizophrenia. According to this hypothesis, the excess dopamine or extra sensitivity to this neurotransmitter triggers a flood of unrelated thoughts, feelings, and perceptions. Delusions are then attempts to organize these disconnected events into a coherent, understandable experience (Kapur, 2003).

Consistent with the dopamine hypothesis, neuroimaging studies of people with schizophrenia have found abnormally low numbers of dopamine receptors in their frontal lobes (Okubo et al., 1997), as well as increased production of dopamine (possibly to compensate for the reduced numbers of receptors in the frontal lobes) in the striatum (parts of the basal ganglia that produce dopamine; Heinz, 2000). Nevertheless, research has definitively documented that the dopamine hypothesis was an oversimplification (McDermott & de Silva, 2005). Dopamine affects, and is affected by, other neurotransmitters that, in combination with the structural and functional abnormalities of various brain areas, give rise to some of the symptoms of schizophrenia (Vogel et al., 2006; Walker & Diforio, 1997).

Serotonin and Glutamate

Medications that affect serotonin levels can decrease both positive and negative symptoms in people with schizophrenia. However, this finding does not imply that serotonin levels per se are the culprit. Research studies suggest complex interactions among serotonin, dopamine, and glutamate (Andreasen, 2001). For example, serotonin has been shown to enhance the effect of glutamate, which is the most common fast-acting excitatory neurotransmitter in the brain (Aghajanian & Marek, 2000). Studies have found unusually high levels of glutamate in people with schizophrenia, particularly in the frontal lobe (Abbott & Bustillo, 2006; van Elst et al., 2005); such an excess of glutamate may disrupt the timing of neural activation in the frontal lobe, which in turn may impair cognitive activities (Lewis & Moghaddam, 2006).

Stress and Cortisol

Research findings suggest that stress can contribute to schizophrenia because stress affects the production of the hormone cortisol, which in turn affects the brain. In fact, children who are at risk for developing schizophrenia react more strongly to stress, and their baseline levels of cortisol are higher than those of other children (Walker et al., 1999). The relationship between stress, cortisol, and symptoms of schizophrenia has also been noted during adolescence, the time when prodromal symptoms often emerge: A 2-year longitudinal study of adolescents with schizotypal personality disorder found that cortisol levels—and symptoms of schizophrenia—increased over the 2 years (Walker et al., 2001). Even after adolescence, people with schizophrenia have higher levels of stress-related hormones, including cortisol (Zhang et al., 2005).

Thus, people who develop schizophrenia appear to be unusually biologically reactive to stressful events. A hypothesized mechanism for this relationship is that the biological changes and stressors of adolescence promote higher levels of cortisol, which may then affect dopamine activity. The relationship between cortisol and schizophrenia is supported by research indicating that anti-inflammatory medications (such as aspirin or other types of drugs referred to as COX-2 inhibitors), which indirectly reduce the levels of cortisol, reduce the symptoms of schizophrenia (Keller et al., 2013).

Effects of Estrogen

GETTING THE PICTURE

© Jon Feingersh Photography/SuperStock/Corbis

We noted earlier that when women develop schizophrenia, they often have different symptoms than men do, and they tend to function better. Such findings have led to the estrogen protection hypothesis (Seeman & Lang, 1990). According to this hypothesis, the hormone estrogen, which is present at higher levels in women than in men, protects against symptoms of schizophrenia via its effects on serotonin and dopamine. This protection may explain why women typically develop the disorder later in life than do men. Evidence for the estrogen protection hypothesis comes from two sources. One is the finding that women with schizophrenia who had higher levels of estrogen also had better cognitive functioning (Hoff et al., 2001). The other is the finding that constant doses of estrogen provided by a skin patch (in addition to antipsychotic medication) reduced the positive symptoms of women with severe schizophrenia more than did antipsychotic medication without supplementary estrogen (Kulkarni et al., 2008).

384

Genetics

Various twin, family, and adoption studies indicate that genes play a role in schizophrenia (Aberg et al., 2013; Tienari et al., 2006; Wicks et al., 2010; Wynne et al., 2006). The more genes a person shares with a relative who has schizophrenia, the higher the risk that that person will also develop schizophrenia (see TABLE 12.7). However, even for those who have a close relative with schizophrenia, the chance of developing the disorder is still relatively low: More than 85% of people who have one parent or one sibling (who is not a twin) with the disorder do not go on to develop it themselves (Gottesman & Moldin, 1998)—and this percentage is even higher for people with a grandparent, aunt, or uncle (second-degree relatives) with the disorder (Gottesman & Erlenmeyer-Kimling, 2001). Nonetheless, a family history of schizophrenia is still the strongest known risk factor for developing the disorder (Hallmayer, 2000).

| Family member(s) with schizophrenia | Risk of developing schizophrenia |

|---|---|

| First cousin | 2% |

| Half-sibling | 6% |

| Full sibling | 9% |

| One parent | 13% |

| Two parents | 46% |

| Fraternal twin | 14–17% |

| Identical twin | 46–53% |

| Sources: Gottesman, 1991; Kendler, 1983. | |

If the cause of schizophrenia were entirely genetic, then when one identical twin developed the disorder, the co-twin would also develop the disorder; that is, the co-twin’s risk of developing schizophrenia would be 100%. But this is not what happens; the actual risk of a co-twin’s developing schizophrenia ranges from 46 to 53% (in different studies), as shown in TABLE 12.7.

385

However, identical twins have the same predisposition for developing schizophrenia, although only one of them may develop it. This means that even if only one twin in a pair develops the disorder, the children of both twins (the one with the disorder and the one without) have the same genetic risk of developing it. That is, both the affected and the unaffected twin transmit the same genetic vulnerability to their offspring (Gottesman & Bertelsen, 1989).

As evident from the studies of twins, genes alone do not determine whether someone will develop schizophrenia; rather, the interaction between genes and environment is crucial (Owen et al., 2011). For example, in one illustrative study, researchers tracked two groups of adopted children: those whose biological mothers had schizophrenia and those whose biological mothers did not (considered the control group). None of the adoptive parents of these children had schizophrenia, but some adoptive families were dysfunctional—and the children often experienced stress (Tienari et al., 1994, 2006). In the control group, the incidence of schizophrenia was no higher than in the general population, regardless of the characteristics of the adoptive families. In contrast, the children whose biological mothers had schizophrenia and whose adoptive families were dysfunctional were much more likely to develop schizophrenia than were the children whose biological mothers had schizophrenia but whose adoptive families were not dysfunctional. Thus, better parenting appeared to protect children who were genetically at risk for developing schizophrenia.

Psychological Factors in Schizophrenia

We have seen that schizophrenia is not entirely a consequence of brain structure, brain function, or genetics. As the neuropsychosocial approach implies, schizophrenia arises from a combination of different sorts of factors. For example, the neurocognitive deficits that plague people with schizophrenia also affect how they perceive the social world, and their perceptions affect their ability to function in that world (Sergi et al., 2006). If we understand their experiences, their behaviors may not appear so bizarre. However, not every person with schizophrenia experiences each type of difficulty we discuss in the following sections (Walker et al., 2004).

Mental Processes and Cognitive Difficulties: Attention, Memory, and Executive Functions

We’ve already noted problems with attention, working memory, and executive function in schizophrenia. Let’s now consider how such problems may contribute to the disorder.

The difficulties with attention—specifically in being able to focus on relevant stimuli and ignore irrelevant stimuli—occur even when the person is taking medication and isn’t psychotic (Cornblatt et al., 1997). This attentional problem can make it hard for people with schizophrenia to discern which stimuli are important and which aren’t; such people may feel overwhelmed by a barrage of stimuli. This leads to problems in organizing what they perceive and experience, which would contribute to their difficulties with perception and memory (Sergi et al., 2006).

Another cognitive problem common to people with schizophrenia is that they often don’t realize that they are having unusual experiences or behaving abnormally; this inability is referred to as a lack of insight. Thus, they are unaware of their disorder or the specific problems it creates for themselves and others (Amador & Gorman, 1998) and see no need for treatment (Buckley et al., 2007). In Case 12.2, psychologist Fred Frese discusses his lack of insight into his own schizophrenia and its effects.

386

CASE 12.2 • FROM THE INSIDE: Schizophrenia

Psychologist Fred Frese describes his history with schizophrenia:

I was 25 years old, and I was in the Marine Corps at the time, and served two back to back tours in the Far East, mostly in Japan. And when I came back I was a security officer in charge of a Marine Corps barracks with 144 men. And we had responsibilities for security for atomic weapons…and a few other duties. About 6 months into that assignment, I made a discovery—to me it was a discovery—that somehow the enemy had developed a new weapon by which they could psychologically hypnotize certain high-ranking officials. And I became very confident that I had stumbled onto this discovery. And because it was a psychological sort of thing I would share this with a person who would be likely to know most about this kind of stuff and that was the base psychiatrist. So I called him up and he agreed to see me right away, and I went down and told him about my discovery, and he listened very politely and when I got finished to get up and leave there were these two gentlemen in white coats on either side of me—either shoulder. And I often say I think one of them looked like he might be elected governor of Minnesota somewhere along the way. But they escorted me down into a seclusion padded room [sic]. And within a day or two I discovered that they had me labeled as paranoid schizophrenic. Of course I immediately recognized that the psychiatrist was under the control of the enemies with their new weapons. I spent about 5 months mostly in Bethesda, which is the Navy’s major hospital, and was discharged with a psychiatric condition. However, that was my discovery that I was diagnosed with…schizophrenia. The way the disorder works is, I didn’t have a disorder, I had “made this discovery”. So it was a number of years before I came to this conclusion that there was something wrong here and I was hospitalized about ten times, almost always involuntarily…over about a 10-year period of time.

(WCPN, 2003).

To develop a sense of the consequences of having such cognitive difficulties, imagine the experience of a man with these deficits who tries to go shopping for ingredients for dinner. He may find himself in the supermarket, surrounded by hundreds of food items; because of his attentional problems, each item on a shelf may capture the same degree of his attention. Because of deficits in executive functioning, he loses track of why he is there—what was he supposed to buy? And if he remembers why he is there (“I need to get chicken, rice, and vegetables”), he may not be able to exercise good judgment about how much chicken to buy or which vegetables. Or, because of the combination of his cognitive deficits, he may find the whole task too taxing and leave without the dinner ingredients.

Beliefs and Attributions

Cognitive deficits that are present before symptoms occur affect what the person comes to believe. For example, because children with such cognitive deficits may do poorly in school and often are socially odd, they may be ostracized or teased by their classmates; they may then come to believe that they are inferior and proceed to act in accordance with that belief, perhaps by withdrawing from others (Beck & Rector, 2005).

In addition, if people with schizophrenia have delusional beliefs, the delusions almost always relate to themselves and their extreme cognitive distortions (e.g., “The FBI is out to get me”). These distortions influence what they pay attention to and what beliefs go unchallenged. People with schizophrenia may be inflexible in their beliefs or may jump to conclusions, and their actions based on their beliefs can be extreme (Garety et al., 2005). Moreover, they may be very confident that their (false) beliefs are true (Moritz & Woodward, 2006). For example, a man with paranoid schizophrenia might attribute a bad connection on a cell phone call to interference by FBI agents or aliens; he searches for and finds “confirming evidence” of such interference (“There’s a bad connection when I call my friend and they want to listen in, but there’s no static when I call for a weather report and there’s no need for them to listen in”). Disconfirming evidence—that cell phone service is weak in the spot where he was standing when he made the call to his friend—is ignored (Beck & Rector, 2005).

387

Similarly, people with schizophrenia who have auditory hallucinations do not generally try to discover where the sounds of the hallucinations are coming from. For example, they don’t check whether the radio is on or whether people are talking in the hallway. They are less likely to question the reality of an unusual experience (that is, whether it arises from something outside themselves) and so do not correct their distorted beliefs (Johns et al., 2002).

Negative symptoms can also give rise to unfounded beliefs; specifically, people who have negative symptoms generally overestimate the extent of their deficits and are particularly likely to have low expectations of themselves. Although such low expectations could indicate an accurate assessment of their abilities, research suggests that this is generally not the case. When cognitive therapy successfully addresses the negative self-appraisals of people with schizophrenia, their functioning subsequently improves (Rector et al., 2003). This finding suggests that the negative self-appraisals are distorted beliefs that became self-fulfilling prophecies (Beck & Rector, 2005).

Emotional Expression

Paul Ekman, Ph.D., Paul Ekman Group, LLC

Paul Ekman, Ph.D., Paul Ekman Group, LLC

Paul Ekman, Ph.D., Paul Ekman Group, LLC

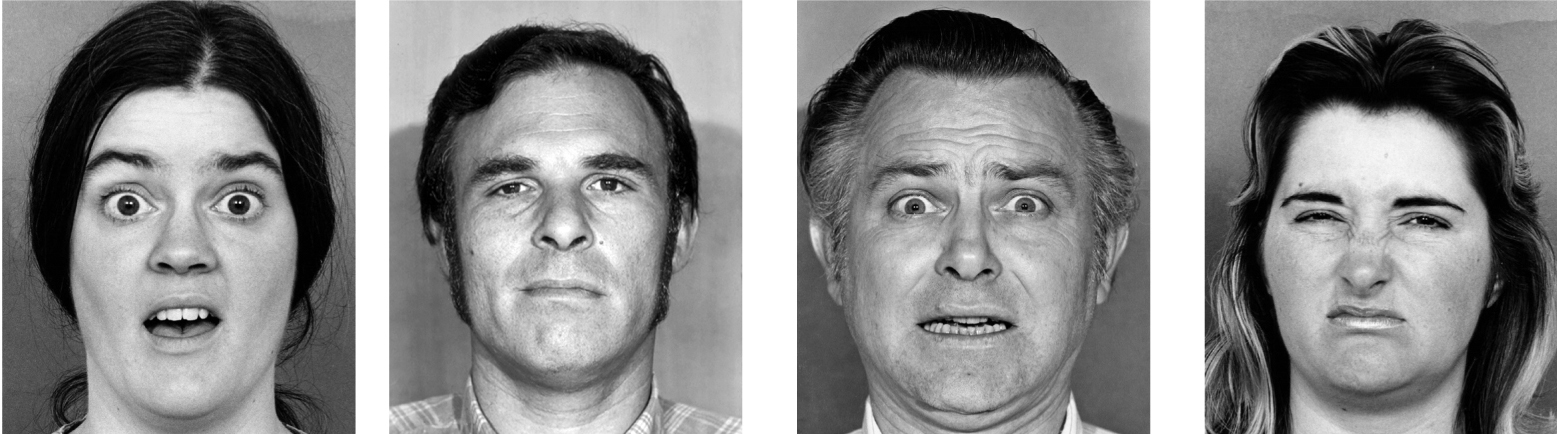

Another psychological factor is the facial expressions of people with schizophrenia, which are less pronounced than those of people who do not have the disorder (Brozgold et al., 1998). Moreover, people with schizophrenia are less accurate than control participants in labeling the emotions expressed by faces they are shown (Penn & Combs, 2000; Schneider-Axmann et al., 2006). Part of the explanation for problems related to emotional expression may be the cognitive deficits. Because they cannot “read” nonverbal communication well, they are confused when someone’s words and subsequent behavior are at odds; people with schizophrenia are likely to miss the nonverbal communication that helps most people make sense of the apparent inconsistency between what others say and what they do (Greig et al., 2004). In fact, even biological relatives of people with schizophrenia tend to have problems understanding other people’s nonverbal communication (Janssen et al., 2003), which suggests that neurological factors are involved.

Social Factors in Schizophrenia

We’ve seen that schizophrenia often includes difficulty in understanding and navigating the social world. We’ll now examine this difficulty in more detail and also consider the ways that economic circumstances and cultural factors can influence schizophrenia.

388

Understanding the Social World

Theory of mind A theory about other people’s mental states (their beliefs, desires, and feelings) that allows a person to predict how other people will react in a given situation.

Each of us develops a theory of mind—a theory about other people’s mental states (their beliefs, desires, feelings) that allows us to predict how they will behave in a given situation. People with schizophrenia have difficulty with tasks that require an accurate theory of mind (Russell et al., 2006) and may thus find relating to others confusing. Because people with schizophrenia have difficulty interpreting emotional expression in others, they don’t fully understand the messages people convey. The symptoms of paranoia and social withdrawal in people with schizophrenia may directly result from this social confusion (Frith, 1992). To a person with schizophrenia, other people can seem to behave in random and unpredictable ways. Thus, it makes sense that such a person tries to explain other people’s seemingly odd behavior (persecutory delusion) or else tries to minimize contact with others because their behavior seems inexplicable.

Despite the fact that they were basically genetically identical, the Genain quads did not have the same level of social skills or ability to navigate the social world. For instance, Myra had markedly better social skills and social desires than her sisters, and was able to work as a secretary for most of her life—a job that requires social awareness and social skills (Mirsky et al., 2000).

Stressful Environments

Orphanages are notoriously stressful environments, which may be one reason why being raised in an orphanage increases the likelihood of later developing schizophrenia in those who are genetically vulnerable. In fact, children born to a parent with schizophrenia are more likely to develop schizophrenia as adults if they were raised in an institution than if they were raised by the parent with schizophrenia (Mednick et al., 1998).

High expressed emotion (high EE) A family interaction style characterized by hostility, unnecessary criticism, or emotional overinvolvement.

Stress also contributes to whether someone who recovered from schizophrenia will relapse (Gottesman, 1991). Almost two thirds of people hospitalized with schizophrenia live with their families after leaving the hospital. These families can create a stressful environment for a person with schizophrenia, especially if the family is high in expressed emotion. The concept of high expressed emotion (high EE) is not aptly named: It’s not just that the family with this characteristic expresses emotion in general but rather that family members express critical and hostile emotions and are overinvolved (for example, by frequently criticizing or nagging the patient to change his or her behavior; Wuerker et al., 2002). In fact, hospitalized patients who return to live with a family high in EE are more likely to relapse than patients who do not return to live with such a family (Butzlaff & Hooley, 1998; Kavanagh, 1992). The Genain quads certainly experienced significant stress, and their family would be considered high in EE.

The relationship between high EE and relapse of schizophrenia is a correlation. High EE probably does not cause schizophrenia in the first place, but it may contribute to a relapse. However, it is also possible that the causality goes the other way—that people whose symptoms of schizophrenia are more severe between episodes elicit more attempts by their family members to try to minimize the positive or negative symptoms. And then these behaviors lead the family to be classified as high in EE. This explanation may apply, in part, to the Genain family: Among the four sisters, Hester’s symptoms were the most chronic and debilitating. She received the most physical punishment, including being whipped and having her head dunked in water, often in response to behaviors that her father wanted her to stop.

Researchers have also discovered ethnic differences in how patients perceive critical and intrusive family behaviors. Among Black American families, for instance, behaviors by family members that focus on problem solving are associated with a better outcome for the person with schizophrenia, perhaps because such behaviors are interpreted as reflecting caring and concern (Rosenfarb et al., 2006). Thus, what is important is not the family behavior in and of itself but how such behavior is perceived and interpreted by family members.

389

Immigration

A well-replicated finding is that schizophrenia is more common among immigrants than among people who stayed in the immigrants’ original country and people who are natives in the immigrants’ adopted country (Cantor-Graae & Selten, 2005; Lundberg et al., 2007; Veling et al., 2012). This higher rate of schizophrenia among immigrants occurs among people who have left a wide range of countries and among people who find new homes in a range of European countries. In fact, one meta-analysis found that being an immigrant was the second largest risk factor for schizophrenia, after a family history of this disorder (Cantor-Graae & Selten, 2005). Both first-generation immigrants—that is, those who left their native country and moved to another country—and their children have relatively high rates of schizophrenia; this is especially true for immigrants and their children who have darker skin color than the natives of the adopted country, which is consistent with the role of social stressors (discrimination in particular) in schizophrenia (Selten et al., 2007). For instance, the increased rate of schizophrenia among African-Caribbean immigrants to Britain (compared to British and Caribbean residents who are not immigrants) may arise from the stresses of immigration, socioeconomic disadvantage, and racism (Jarvis, 1998). Researchers have sought to rule out potential confounds such as illness or nutrition, and have found that such factors do not explain the higher risk of schizophrenia among immigrants. Case 12.3 describes the symptoms of schizophrenia of an immigrant from Haiti to the United States.

CASE 12.3 • FROM THE OUTSIDE: Schizophrenia

Within a year after immigrating to the United States, a 21-year-old Haitian woman was referred to a psychiatrist by her schoolteacher because of hallucinations and withdrawn behavior. The patient was fluent in English, although her first language was Creole. Her history revealed that she had seen an ear, nose, and throat specialist in Haiti after her family doctor could not find any medical pathology other than a mild sinus infection. No hearing problems were noted and no treatment was offered. Examination revealed extensive auditory hallucinations, flat affect, and peculiar delusional references to voodoo. The psychiatrist wondered if symptoms of hearing voices and references to voodoo could be explained by her Haitian background, although the negative symptoms seem unrelated. As a result, he consulted with a Creole-speaking, Haitian psychiatrist.

The Haitian psychiatrist interviewed the patient in English, French, and Creole. Communication was not a problem in any language. He discovered that in Haiti, the patient was considered “odd” by both peers and family, as she frequently talked to herself and did not work or participate in school activities. He felt that culture may have influenced the content of her hallucinations and delusions (i.e., references to voodoo) but that the bizarre content of the delusions, extensive hallucinations, and associated negative symptoms were consistent with the diagnosis of schizophrenia.

(Takeshita, 1997, pp. 124–125)

390

In Case 12.3, notice that, although the women had odd and prodromal behaviors in Haiti, her full-blown symptoms did not emerge until she immigrated to the United States. These symptoms could have emerged when she got older even if she had stayed in Haiti. As compelling as single cases can be, full-scale studies—with adequate controls—must play a central role in helping us understand psychological disorders.

Economic Factors

Social selection hypothesis The hypothesis that people who are mentally ill “drift” to a lower socioeconomic level because of their impairments; also referred to as social drift.

Another social factor associated with schizophrenia is socioeconomic status. A disproportionately large number of people with schizophrenia live in urban areas and among lower economic classes (Hudson, 2005; Mortensen et al., 1999). As discussed in Chapter 2, researchers have offered two possible explanations for this association between the disorder and economic status: social selection and social causation (Dauncey et al., 1993). The social selection hypothesis proposes that people who are mentally ill “drift” to a lower socioeconomic level because of their impairments (and hence social selection is sometimes called social drift). Consider a young woman who grows up in a middle-class family and moves to a distant city after college, and where, after she graduates, she supports herself reasonably well working full time. She subsequently develops schizophrenia but refuses to return home to her family, who cannot afford to send her much money. Her income now consists primarily of meager checks from governmental programs—barely enough to cover food and housing in a poor section of town where rent is cheapest. She has drifted from the middle class to a lower class.

Social causation hypothesis The hypothesis that the daily stressors of urban life, especially as experienced by people in a lower socioeconomic class, trigger mental illness in those who are vulnerable

Another possible explanation is the social causation hypothesis: The daily stressors of urban life, especially for the poor, trigger mental illness in people who are vulnerable (Freeman, 1994; Hudson, 2005). Social causation would explain cases of schizophrenia in people who grew up in a lower social class. The stressors these people experience include poverty or financial insecurity, as well as living in neighborhoods with higher crime rates. Both hypotheses—social selection and social causation—may be correct.

Cultural Factors: Recovery in Different Countries

Although the prevalence of schizophrenia is remarkably similar across countries and cultures, the same cannot be said about recovery rates. Some studies report that people in developing countries have higher recovery rates than do people in industrialized countries (Kulhara & Chakrabarti, 2001), although this was not found in all earlier studies (Edgerton & Cohen, 1994; von Zerssen et al., 1990).

If the results from the more recent studies can be replicated, what might account for this cultural difference? The important distinction may not be the level of industrial and technological development of a country but how individualist its culture is. Individualist cultures stress values of individual autonomy and independence. In contrast, collectivist cultures emphasize the needs of the group, group cohesion, and interdependence. Collectivist cultures may more readily help people with schizophrenia be a part of the community at whatever level is possible. And in fact, people with schizophrenia in collectivist cultures, such as those of Japan, Hong Kong, and Singapore, have a more favorable course and prognosis than people with schizophrenia in individualist cultures such as the United States (Lee et al., 1991; Tsoi & Wong, 1991).

391

The collectivist characteristics of a culture may help a patient to recover for several reasons. Consider that people in collectivist countries may:

- be more tolerant of people with schizophrenia and therefore less likely to be critical, hostile, and controlling toward them. In particular, the families of patients with schizophrenia may be more likely to have lower levels of expressed emotion, decreasing the risk of relapse and leading to better recoveries (El-Islam, 1991).

- elevate the importance of community and, in so doing, provide a social norm that creates more support for people with schizophrenia and their families.

- have higher expectations of people with schizophrenia—believing that such people can play a functional role in society—and these expectations become a self-fulfilling prophecy (Mathews et al., 2006).

Thus, collectivism—and the strong family values that usually accompany it—may best explain the better recovery rates in less developed countries, which are generally more collectivist (Weisman, 1997). In fact, for Latino patients, increasing their perception of the cohesiveness of the family is associated with fewer psychiatric symptoms and less distress (Weisman et al., 2005).

Feedback Loops in Understanding Schizophrenia

No individual risk factor by itself accounts for a high percentage of the cases of schizophrenia. Genetics, prenatal environmental events (such as maternal malnutrition and maternal illness), and birth complications that affect fetal development (neurological factors) can increase the likelihood that a person will develop schizophrenia. But many people who have these risk factors do not develop the disorder. Similarly, cognitive deficits (psychological factors) can contribute to the disorder because they create cognitive distortions, but such factors do not actually cause schizophrenia. And a dysfunctional family or another type of stressful environment (social factors), again, can contribute to, but do not cause, schizophrenia.

As usual, in determining the origins of psychopathology, no one factor reigns supreme in producing schizophrenia; instead, the feedback loops among the three types of factors provide the best explanation (Mednick et al., 1998; Tienari et al., 2006). To get a more concrete sense of the effects of the feedback loops, consider the fact that economic factors (which are social) can influence whether a pregnant woman is likely to be malnourished, which in turn affects the developing fetus (and his or her brain). And various social factors create stress (and not simply among immigrants or among children raised in an orphanage—but for all of us). The degree of stress a person experiences (a psychological factor) in turn can trigger factors that affect brain function, including increased cortisol levels. Coming full circle, as shown in Figure 12.3, these psychological and neurological factors are affected by culture (a social factor), which influences the prognosis, how people with schizophrenia are viewed, and how they come to view themselves (psychological factors).

The Genain quads illustrate the effects of these feedback loops. A family history of schizophrenia as well as prenatal complications made the quads neurologically vulnerable to developing schizophrenia. They were socially isolated, were teased by other children, and experienced physical and emotional abuse. Had the Genain quads grown up in a different home environment, with parents who treated them differently, it is possible that some of them might not have developed schizophrenia, and those who did might have suffered fewer relapses.

392

Thinking Like A Clinician

Using the neuropsychosocial approach, explain in detail how the three types of factors and their feedback loops may have led all four Genain sisters to develop schizophrenia —and formulate a hypothesis to explain why they had some different symptoms.