12.3 Treating Schizophrenia

The Genain sisters were treated at NIMH and then subsequently in hospitals, residential settings, and community mental health centers. During the early years of the quads’ illness, antipsychotic medications were only just beginning to be used, and treatments that target psychological and social factors have changed substantially since then. Today, treatment for schizophrenia occurs in steps, with different symptoms and problems targeted in each step (Green, 2001):

393

STEP 1: When the patient is actively psychotic, first reduce the positive symptoms.

STEP 2: Reduce the negative symptoms.

STEP 3: Improve neurocognitive functioning.

STEP 4: Reduce the person’s disability and increase his or her ability to function in the world.

As we’ll see, the last step is the most challenging.

Targeting Neurological Factors in Treating Schizophrenia

At present, interventions targeting neurological factors generally focus on the first two steps of treatment: reducing positive and negative symptoms. However, some such treatments address on the third step: improving cognitive function.

Medication

Doctors began to use medication to treat symptoms of schizophrenia in the 1950s, with the development of the first antipsychotic (also called neuroleptic) medication, thorazine. Since then, various antipsychotic medications have been developed, and two general types of these medications are now used widely, each with its own set of side effects.

Traditional Antipsychotics

Thorazine (chlorpromazine) and other similar antipsychotics are dopamine antagonists, which effectively block the action of dopamine. Positive symptoms—hallucinations and delusions—diminish in approximately 75–80% of people with schizophrenia who take such antipsychotic medications (Green, 2001). Since their development, traditional antipsychotics have been the first step in treating schizophrenia. When taken regularly, they can reduce the risk of relapse: Only 25% of those who took antipsychotic medication for 1 year had a relapse, compared to 65–80% of those not on medication for a year (Rosenbaum et al., 2005). Traditional antipsychotics quickly sedate patients; above and beyond such sedation, psychotic symptoms start to improve anywhere from 5 days to 6 weeks after the patient begins to take the medication (Rosenbaum et al., 2005).

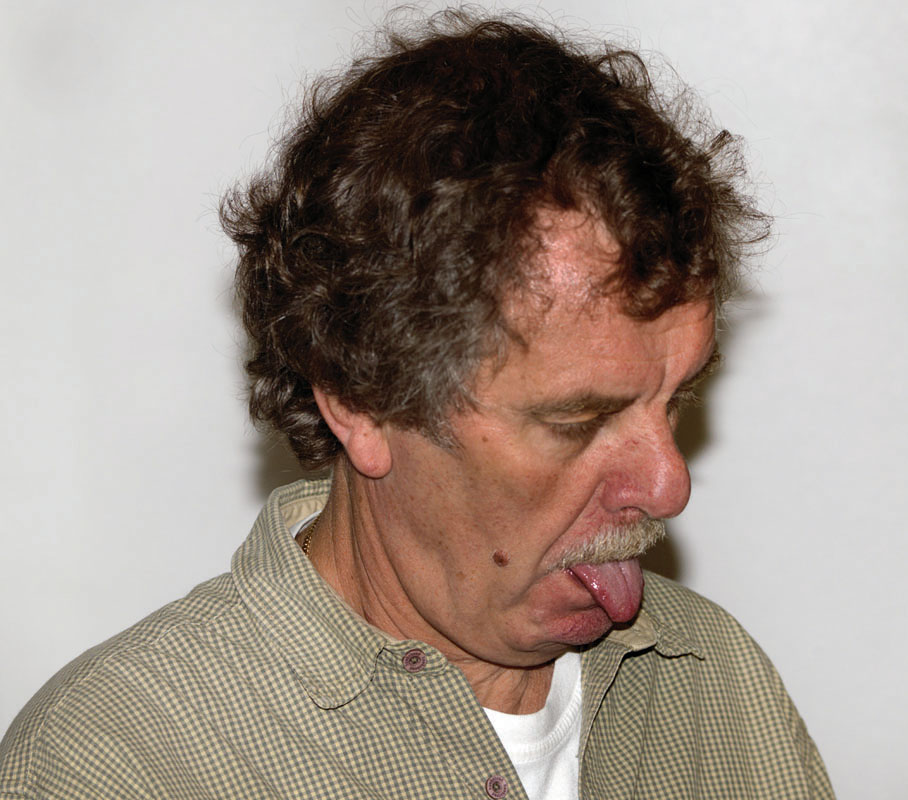

Tardive dyskinesia An enduring side effect of traditional antipsychotic medications that produces involuntary lip smacking and odd facial contortions as well as other movement-related symptoms.

Some of the side effects of traditional antipsychotics create problems when a person takes them regularly for an extended period of time. For example, patients can develop tardive dyskinesia, an enduring side effect that produces involuntary lip smacking and odd facial contortions as well as other movement-related symptoms. Although tardive dyskinesia typically does not go away even when traditional antipsychotics are discontinued, its symptoms can be reduced with another type of medication. Other side effects of traditional antipsychotics include tremors, weight gain, and a sense of physical restlessness.

Atypical Antipsychotics: A New Generation

Atypical antipsychotics A relatively new class of antipsychotic medications that affects dopamine and serotonin activity; also referred to as second-generation antipsychotics.

More recently, doctors have been able to use a different class of medications to treat schizophrenia: Atypical antipsychotics (also referred to as second-generation antipsychotics) affect dopamine and serotonin. Examples of atypical antipsychotics include Risperdal (risperidone), Zyprexa (olanzapine), and Seroquel (quetiapine). Atypical antipsychotics also can reduce comorbid symptoms of anxiety and depression (Marder et al., 1997). Like traditional antipsychotics, they decrease the likelihood of relapse, at least for 1 year (which is the longest period studied; Csernansky et al., 2002; Lauriello & Bustillo, 2001). However, any benefits of newer antipsychotics must be weighed against medical costs: Side effects include changes in metabolism that cause significant weight gain and increased risk of heart problems, and these side effects can become so severe or problematic that some people won’t or shouldn’t continue to use these medications (McEvoy et al., 2007). In addition, atypical antipsychotics, like traditional antipsychotics, sometimes cause tardive dyskinesia (Woods et al., 2010).

394

Either type of antipsychotic medication is considered “successful” when it significantly reduces symptoms and the side effects can be tolerated. However, sometimes medication is not successful because it isn’t really given a fighting chance: Patients often stop taking their prescribed medication without consulting their doctor, which is referred to as noncompliance. Many people who stop taking their medication—whether in consultation with their doctor or not—cite significant unpleasant side effects as the main reason (Lieberman et al., 2005).

Discontinuing Medication

Given how often patients stop taking their medication (up to two thirds in one study; Lieberman et al., 2005), we need to understand the effects of discontinuing medication: When people with schizophrenia discontinue their medication, they are more likely to relapse. One study found that among those who were stable for over 1 year and then stopped taking their medication, 78% had symptoms return within 1 year after that, and 96% had symptoms return after 2 years (Gitlin et al., 2001). And even up to 5 years after discharge, patients who had been hospitalized for schizophrenia and then discontinued their medication were five times as likely to relapse as those who didn’t (Robinson et al., 1999).

Brain Stimulation: ECT

Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT) was originally used to treat schizophrenia but generally was not successful. Although currently used only infrequently to treat this disorder, a course of ECT may be administered to people with active schizophrenia who are not helped by medications. ECT may reduce symptoms, but its effects are short lived; furthermore, “maintenance” ECT—that is, regular although less frequent treatments—may be necessary for long-term improvement (Keuneman et al., 2002). Three of the Genain sisters—Nora, Iris, and Hester—received numerous sessions of ECT before antipsychotic medication was available. After ECT, their symptoms improved at least somewhat but, usually within months, if not weeks, worsened again until the symptoms were so bad that a course of ECT was again administered (Mirsky et al., 1987; Rosenthal, 1963).

In experimental studies with small numbers of patients, transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) appears to decrease hallucinations, at least in the short term (Brunelin, Poulet et al., 2006; Poulet et al., 2005). However, not all studies have found this positive effect (McNamara et al., 2001; Saba et al., 2006). The specifics of ECT and TMS administration are discussed in Chapter 5.

Targeting Psychological Factors in Treating Schizophrenia

Treatments for schizophrenia that target psychological factors address three of the four general treatment steps; they (1) reduce psychotic symptoms through cognitive-behavior therapy (CBT); (2) reduce negative symptoms of schizophrenia through CBT; and (3) improve neurocognitive functioning (and quality of life) through psychoeducation and motivational enhancement (Tarrier & Bobes, 2000).

Cognitive-Behavior Therapy

CBT addresses the patient’s symptoms and the distress they cause. Treatment may initially focus on understanding and managing symptoms, by helping patients to:

- learn to distinguish hallucinatory voices from people actually speaking,

- highlight the importance of taking effective medications,

- address issues that interfere with compliance, and

- develop more effective coping strategies.

When a therapist uses CBT to address problems arising from delusions, he or she does not try to challenge the delusions themselves but instead tries to help the patient move forward in life, despite these beliefs. For instance, if a man believes that the CIA is after him, the CBT therapist might focus on the effects of that belief: What if the CIA were following him? How can he live his life more fully, even if this were the case? Patient and therapist work together to implement new coping strategies and monitor medication compliance. In fact, such uses of CBT not only improve overall functioning (Step 4) but also can decrease positive (Pfammatter et al., 2006; Rector & Beck, 2002a, 2002b) and negative symptoms (Grant et al., 2012; Turkington et al., 2006).

395

Treating Comorbid Substance Abuse: Motivational Enhancement

Because many people with schizophrenia also abuse drugs or alcohol, recent research has focused on developing treatments for people with both schizophrenia and substance use disorders; motivational enhancement is one facet of such treatment. As we discussed in Chapter 10, patients who receive motivational enhancement therapy develop their own goals, and then clinicians help them meet those goals. For people who have both schizophrenia and substance use disorders, one goal might be to take medication regularly (Lehman et al., 1998). For people who have two disorders, treatment that targets both of them appears to be more effective than treatment that targets one or the other alone (Barrowclough et al., 2001).

Targeting Social Factors in Treating Schizophrenia

Treatments that target social factors address three of the four general treatment steps: They identify early warning signs of positive and negative symptoms through family education and therapy; when necessary, such treatments involve hospitalizing people who cannot care for themselves or are at high risk of harming themselves or others. These treatments also reduce certain negative symptoms through social skills training and improve overall functioning (and quality of life) through community-based interventions. Community-based interventions include work-related and residential programs (Tarrier & Bobes, 2000).

Family Education and Therapy

By the time a person is diagnosed with schizophrenia, family members typically have struggled for months—or even years—to understand and help their loved one. Psychoeducation for family members can provide practical information about the illness and its consequences, how to recognize early signs of relapse, how to recognize side effects of medications, and how to manage crises that may arise. Such education can decrease relapse rates (McWilliams et al., 2012; Pfammatter et al., 2006). In addition, family-based treatments may provide emotional support for family members (Dixon et al., 2000). Moreover, family therapy can create more adaptive family interaction patterns:

In 1989, my older sister and I joined Mom in her attempts to learn more about managing symptoms of her illness. Mom’s caseworkers met with us every 6 to 8 weeks for over 8 years. Mom, who had never been able to admit she had an illness, now told us that she did not want to die a psychotic. This was one of the many positive steps that we observed in her recovery. Over the years, other family members have joined our group…. With the help of the treatment team, we can now respond effectively to Mom’s symptoms and identify stress-producing situations that, if left unaddressed, can lead to episodes of hospitalization. With Mom’s help we have identified the different stages of her illness. In the first stage, we listed withdrawal, confusions, depression, and sleeping disorder. Fifteen years ago when mom reported her symptoms to me, I just told her everything would be okay. Today we respond immediately. For 8 years she has maintained a low dosage of medications, with increases during times of stress.

(Sundquist, 1999, p. 620)

Family therapy can also help high EE families change their pattern of interaction, so that family members are less critical of the patient, which can lower the relapse rate from 75% to 40% (Leff et al., 1990).

Group Therapy: Social Skills Training

Given the prominence of social deficits in many people with schizophrenia, clinicians often try to improve a patient’s social skills. Social skills training usually occurs in a group setting, and its goals include learning to “read” other people’s behaviors, learning what behaviors are expected in particular situations, and responding to others in a more adaptive way. Social skills training teaches these skills by breaking complex social behaviors into their components: maintaining eye contact when speaking to others, taking turns speaking, learning to adjust how loudly or softly to speak in different situations, and learning how to behave when meeting someone new. The leader and members of a group take turns role-playing these different elements of social interaction.

396

In contrast to techniques that focus specifically on behaviors, cognitive techniques focus on group members’ irrational beliefs about themselves, their knowledge of social conventions, the beliefs that underlie their interactions with other people, and their ideas about what others may think; such beliefs often prevent people with schizophrenia from attempting to interact with others. Each element of the training is repeated several times, to help patients overcome their neurocognitive problems when learning new material.

Inpatient Treatment

Short-term or long-term hospitalization is sometimes necessary for people with schizophrenia. A short-term hospital stay may be required when someone is having an acute schizophrenic episode (that is, is actively psychotic, extremely disorganized, or otherwise unable to care for himself or herself) or is suicidal or violent. The goal is to reduce symptoms and stabilize the patient. Once hospitalized, the patient will probably receive medication and therapy. The patient may participate in various therapy groups, such as a group to discuss side effects of medications. Once the symptoms are reduced to the point where appropriate self-care is possible and the risk of harm is minimized, the patient will probably be discharged. Long-term hospitalization may occur only when treatments have not significantly reduced symptoms and the patient needs full-time intensive care.

Legal measures have made it difficult to hospitalize people against their will (Torrey, 2001). Although these tougher standards protect people from being hospitalized simply because they do not conform to common social conventions (see Chapter 1), they also have downsides: People who have a disorder that by its very nature limits their ability to comprehend that they have an illness may not receive appropriate help until their symptoms have become so severe that they are dangerous to themselves or others, or they are unable to take care of themselves adequately. Early intervention for ill adults who do not want help but do not realize that they are ill is legally almost impossible today. This issue will be discussed in more detail in Chapter 16.

Minimizing Hospitalizations: Community-Based Interventions

In Chapter 1 we noted that asylums and other forms of 24-hour care, treatment, and containment for those with severe mental illness have met with mixed success over the past several hundred years. Traditionally, people with chronic schizophrenia were likely to end up in such institutions. However, beginning in the 1960s, with the widespread use of antipsychotic medications, the U.S. government established the social policy of deinstitutionalization—trying to help those with severe mental illness live in their communities rather than remain in the hospital. Not everyone thinks that deinstitutionalization is a good idea, at least not in the way it has been implemented. The main problem is that the patients were sent out into communities without adequate social, medical, or financial support. It is now common in many U.S. cities to see such people on street corners, begging for money or loitering, with no obvious social safety net.

Community care Programs that allow mental health care providers to visit patients in their homes at any time of the day or night; also known as assertive community treatment.

The good news is that some communities have adequately funded programs to help people with chronic schizophrenia (and other chronic and debilitating psychological disorders) live outside institutions. Community care (also known as assertive community treatment) programs allow mental health staff to visit patients in their homes at any time of the day or night (Mueser, Bond, et al., 1998). Patients who receive such community care report greater satisfaction with their care; however, such treatment may not necessarily lead to better outcomes (Killaspy et al., 2006).

397

Residential Settings

Some people with schizophrenia may be well enough not to need hospitalization but are still sufficiently impaired that they cannot live independently or with family members. Alternative housing for such people includes a variety of supervised residential settings. Some of these patients live in highly supervised housing, in which a small number of people live with a staff member. Residents take turns shopping for and making meals. They also have household chores and attend house meetings to work out the normal annoyances of group living. Those able to handle somewhat more responsibility may live in an apartment building filled with people of similar abilities, with a staff member available to supervise any difficulties that arise. As patients improve, they transition to less supervised settings.

Vocational Rehabilitation

Various types of programs assist people with schizophrenia to acquire job skills; such programs are specifically aimed at helping patients who are relatively high functioning but have residual symptoms that interfere with functioning at, or near, a normal level. For instance, patients who are relatively less impaired may be part of supported employment programs, which place people in regular work settings and provide an onsite job coach to help them adjust to the demands of the job itself and the social interactions involved in having a job (Bustillo et al., 2001). Examples of supported employment jobs might include work in a warehouse, packaging items for shipment or restocking items in an office or a store (“Project search,” 2006). Those who are more impaired may participate in sheltered employment, working in settings that are specifically designed for people with emotional or intellectual problems who cannot hold a regular job. For example, people in such programs may work in a hospital coffee shop or create craft items that are sold in shops.

What predicts how well a patient with schizophrenia can live and work in the world? Researchers have found that a person’s ability to live and perhaps work outside a hospital is associated with a specific cognitive function: his or her ability to use working memory (Dickinson & Coursey, 2002).

Details of the treatment that the Genain sisters received are only available for their time at NIMH in the 1950s, when less was known about the disorder and how to treat it effectively. During the sisters’ stay at NIMH, therapists tried to reduce the parents’ level of emotional expressiveness and criticism; however, such attempts do not appear to have been effective. After their departure from NIMH, the sisters lived in a variety of settings: Nora lived first with Mrs. Genain and subsequently in a supervised apartment with Hester. Iris was less able to live independently and lived in the hospital, in supervised residential settings, or at home with Mrs. Genain; she died in 2002. Myra, long divorced, generally lived independently; after Mrs. Genain died in 1983, Myra moved into her mother’s house with her older son. Like Iris, Hester spent many years in the hospital and then with Mrs. Genain. She lived with Nora in a supervised apartment until she died in 2003 (Mirsky & Quinn, 1988; Mirsky et al., 1987, 2000).

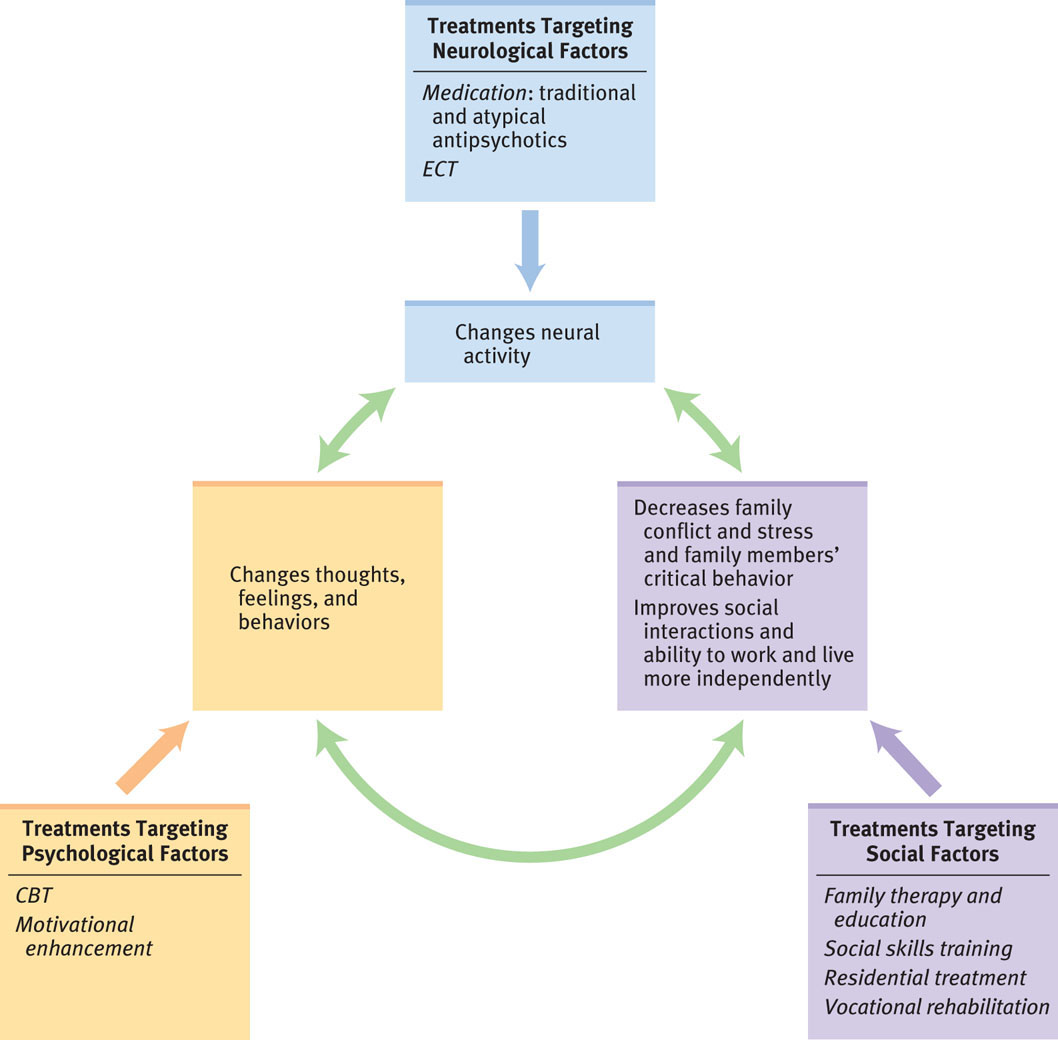

Feedback Loops in Treating Schizophrenia

To be effective, treatment for people with schizophrenia must employ interventions that induce interactions among neurological, psychological, and social factors (see Figure 12.4). When successful, medication (treatment targeting neurological factors) can reduce the positive and negative symptoms and even help improve cognitive functioning. These changes in neurological and psychological factors, in turn, make it possible for social treatments, such as social skills training and vocational rehabilitation, to be effective. If patients are not psychotic and have improved cognitive abilities, they can better learn social and vocational skills that allow them to function more effectively and independently. Moreover, to the extent that the patients function more effectively, they may experience less stress, which reduces cortisol levels—which in turn affects neurological functioning. And such improved neurological functioning can further facilitate cognitive functioning, which helps the patients live in the social world.

398

Thinking Like A Clinician

Suppose you are designing a comprehensive treatment program for people with schizophrenia. Although you’d like to provide each program participant with many types of services, budgetary constraints mean that you have to limit the types of treatments your program offers. Based on what you have read about the treatment of schizophrenia, what would you definitely include in your treatment program, and why? Also list the types of treatment you’d like to include if you had a bigger budget.