13.1 Diagnosing Personality Disorders

It’s not unusual for children to act out in school, as Rachel Reiland did. But as children get older, they mature. In Reiland’s case, she went on to do well academically in high school and college, but in the nonacademic areas of her life, things didn’t go as well. While in high school, she developed anorexia nervosa. In high school and college, she frequently got drunk and had numerous casual sexual encounters. Moreover, she hadn’t yet grown out of the maladaptive childhood patterns of behavior that got her into so much trouble.

In her mid-20s, Reiland unintentionally became pregnant when dating a man named Tim. They decided to marry and did so, even though she had a miscarriage before the wedding. They then had two children, first Jeffrey and 2 years later, Melissa. It seemed that Reiland had straightened out her life and that her childhood problems were behind her.

She temporarily stopped working while the children were young. When they were 2 and 4years old, Reiland found herself overwhelmed—alternately angry and needy. One day during this period of her life, her husband called to say he’d be late at work and wouldn’t be home until 6 or 7 P.M. She responded by asking whether his coming home late was her fault. Reiland recounts their ensuing exchange:

“I didn’t say it’s your fault, honey. It’s just that…well, I’ve got to get some stuff done.” I began to twist the phone cord around my finger, tempted to wrap it around my neck.

“I’m a real pain in the ass, aren’t I? You’re pissed, aren’t you?” Tim tried to keep his patience, but I could still hear him sigh.

“Please, Rachel. I’ve got to make a living.”

“Like I don’t do anything around here? Is that it? Like I’m some kind of stupid housewife who doesn’t do a god-damned thing? Is that what you’re getting at?” Another sigh.

“Okay. Look, sweetheart, I’ve got to do this presentation this afternoon because it’s too late to cancel. But I’ll see if I can reschedule the annuity guy for tomorrow. I’ll be home by four o’clock, and I’ll help you clean up the house.”

“No, no, no!”

I was beginning to cry.

“What now?”

“God, Tim. I’m such an idiot. Such a baby. I don’t do a thing around this house, and here I am, wanting you to help me clean. I must make you sick.”

“You don’t make me sick, sweetheart. Okay? You don’t. Look, I’m really sorry, but I’ve got to go.”

The tears reached full strength. The cry became a moan that turned to piercing screams. Why in the hell can’t I control myself? The man has to make a living. He’s such a good guy; he doesn’t deserve me—no one should have to put up with me!

“Rachel? Rachel? Please calm down. Please! Come on. You’re gonna wake up the kids; the neighbors are gonna wonder what in the hell is going on. Rachel?”

“[Screw you!] Is that all you care about, what the neighbors think? [Screw] you, then. I don’t need you home. I don’t want you home. Let this [damn] house rot; let the [damn] kids starve. I don’t give a shit. And I don’t need your shit!”

Personality Enduring characteristics that lead a person to behave in relatively predictable ways across a range of situations.

(2004, pp. 11–12)

When Tim responds by saying he’s going to cancel all his appointments and can be home in a few minutes, she sobs, “You must really hate me…you really hate me, don’t you?” (Reiland, 2004.

Reiland’s behavior seems extreme, but is it so extreme that it indicates a personality disorder, or is it just an emotional outburst from a mother of young children who is feeling overwhelmed? In order to understand the nature of Reiland’s problems and see how a clinician determines whether a person’s problems merit a diagnosis of personality disorder, we must focus on personality, and contrast normal versus abnormal variations of personality.

403

When you describe your roommate or new friends to your parents, you usually describe his or her personality—enduring characteristics that lead a person to behave in relatively predictable ways across a range of situations. Similarly, when you imagine how family members will react to bad news you’re going to tell them, you are probably basing your predictions of their reactions on your sense of their personality characteristics. Such characteristics—or personality traits—are generally thought of as being on a continuum, with a trait’s name, such as “interpersonal warmth,” at one end of the continuum and its opposite, such as “standoffishness,” at other end of the continuum. Each person is unique in terms of the combination of his or her particular personality traits—and how those traits affect his or her behavior in various situations.

In this section we examine in more detail the DSM-5 category of personality disorders and then the specific personality disorders that it contains.

What Are Personality Disorders?

Some people consistently and persistently exhibit extreme versions of personality traits, such as being overly conscientious and rule-bound or, like Reiland, being overly emotional and quick to anger. In some cases, extreme traits are also inflexible—the person cannot easily control or modulate them. Such extreme and inflexible traits can become maladaptive and cause distress or dysfunction—characteristics of a personality disorder. In the following we examine the definition of personality disorders more closely.

As TABLE 13.1 notes, personality disorders reflect persistent thoughts, feelings, and behaviors that are significantly different from the norms in the person’s culture. Specifically, these differences involve the ABCs of psychological functioning:

- affect, which refers to the range, intensity, and changeability of emotions and emotional responsiveness and the ability to regulate emotions;

- behavior, which refers to the ability to control impulses and interactions with others; and

- cognition (mental processes and mental contents), which refers to the perceptions and interpretations of events, other people, and oneself.

|

| Reprinted with permission from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, (Copyright ©2013). American Psychiatric Association. All Rights Reserved. |

The differences in the ABCs of psychological functioning are relatively inflexible and persist across a range of situations, which highlights how central these maladaptive personality traits are to the way the person functions. This rigidity across situations in turn leads to distress or impaired functioning, as it did for Sarah, in Case 13.1. To be diagnosed with a personality disorder, the maladaptive traits typically should date back at least to early adulthood and should not primarily arise from a substance-related or medical disorder or another psychological disorder (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

We can now answer the question of whether Reiland’s difficulties were more than those of an overwhelmed mother of young children: Her problems indicate that she has a personality disorder.

404

CASE 13.1 • FROM THE INSIDE: Personality Disorder

Sarah, a 39-year-old single female, originally requested therapy at…an outpatient clinic, to help her deal with chronic depression and inability to maintain employment. She had been unemployed for over a year and had been surviving on her rapidly dwindling savings. She was becoming increasingly despondent and apprehensive about her future. She acknowledged during the intake interview that her attitude toward work was negative and that she had easily become bored and resentful in all of her previous jobs. She believed that she might somehow be conveying her negative work attitudes to prospective employers and that this was preventing them from hiring her. She also volunteered that she detested dealing with people in general….

Sarah had a checkered employment history. She had been a journalist, a computer technician, a night watch person, and a receptionist. In all of these jobs she had experienced her supervisors as being overly critical and demanding, which she felt caused her to become resentful and inefficient. The end result was always her dismissal or her departure in anger. Sarah generally perceived her co-workers as being hostile, unfair, and rejecting. However, she would herself actively avoid them, complaining that they were being unreasonable and coercive when they tried to persuade her to join them for activities outside of work. For example, she would believe that she was being asked to go for drinks purely because her co-workers wanted her to get drunk and act foolishly. Sarah would eventually begin to take “mental health” days off from work simply to avoid her supervisors and colleagues.

(Thomas, 1994, p. 211)

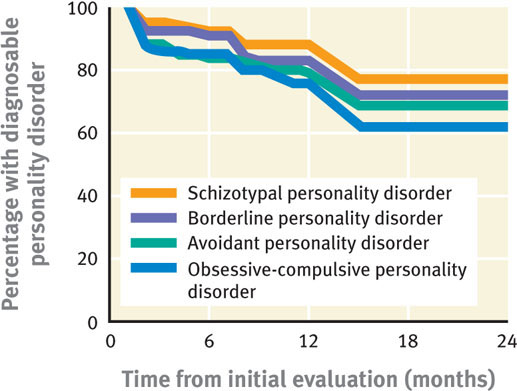

Although personality disorders are considered to be relatively stable, at least from adolescence into adulthood, research suggests that (as shown in Figure 13.1) these disorders are not as enduring as once thought (Clark, 2009; Zanarini et al., 2005); rather, symptoms can improve over time for some people (Grilo et al., 2004; Johnson et al., 2000).

As a group, people with personality disorders obtain less education (Torgersen et al., 2001) and are more likely never to have married or to be separated or divorced (Torgersen, 2005) than people who don’t have such disorders. Personality disorders are associated with suicide: Among people who die by suicide, about 30% apparently had a personality disorder; among people who attempt suicide, about 40% apparently have a personality disorder (American Psychiatric Association Work Group on Suicidal Behaviors, 2003).

Assessing Personality Disorders

Personality disorders can be difficult to diagnose in a first interview, largely because patients may not be aware of the symptoms. In many cases, people who have a personality disorder are so familiar with their lifelong pattern of emotional responses, behavioral tendencies, and mental processes and contents that the ways in which this pattern is maladaptive may not be apparent to them. In fact, most people with a personality disorder identify other people or situations as being the problem, not something about themselves.

Given that many people with personality disorders are not aware of the nature of their problems, clinicians may diagnose a patient with a personality disorder based both on what the patient says and on patterns in the way he or she says it (Skodol, 2005). For instance, Sarah, in Case 13.1, probably had specific complaints about her coworkers, but the key information lies in the pattern of her complaints—in her claim that most of her coworkers, in various companies, were hostile and rejecting. Multiple patient visits may be required to identify such a pattern and to diagnose a personality disorder, more such visits than is usually needed to diagnose other types of disorders. And more than with other diagnoses, clinicians must make inferences about the patient in order to diagnose a personality disorder. However, clinicians must be careful not to assume that their inferences are correct without further corroboration (Skodol, 2005).

405

To help assess personality disorders, clinicians and researchers may interview the patient and also have patients complete personality inventories or questionnaires. To diagnose a personality disorder, the clinician may also talk with someone in the patient’s life, such as a family member—who often describes the patient very differently than does the patient (Clark, 2007; Clifton et al., 2004). The picture that emerges of someone with a personality disorder is a pattern of chronic interpersonal difficulties or chronic problems with self, such as a feeling of emptiness (Livesley, 2001).

According to DSM-5, when clinicians assess personality disorders, they should take into account the person’s culture, ethnicity, and social background. For instance, a woman who appears to be unable to make any decisions independently (even about what to make for dinner) and constantly defers to family members might have a personality disorder. However, for some immigrants, this pattern of behavior may be within a normal range for their ethnic or religious group. When immigrants have problems that are related to the challenges of adapting to a new culture or that involve behaviors or a worldview that is typical of people with their background, a personality disorder shouldn’t be diagnosed. A clinician who isn’t familiar with a patient’s background should get more information from other sources.

DSM-5 Personality Clusters

Cluster A personality disorders Personality disorders characterized by odd or eccentric behaviors that have elements related to those of schizophrenia.

DSM-5 lists 10 personality disorders, grouped into three clusters. Each cluster of personality disorders shares a common feature. Cluster A personality disorders are characterized by odd or eccentric behaviors that have elements related to those of schizophrenia. Cluster B personality disorders are characterized by emotional, dramatic, or erratic behaviors that involve problems with emotional regulation. Cluster C personality disorders are characterized by anxious or fearful behaviors. We will discuss the specific disorders in each cluster as we progress through this chapter. TABLE 13.2 provides an overview of facts about personality disorders in general.

Cluster B personality disorders Personality disorders characterized by emotional, dramatic, or erratic behaviors that involve problems with emotional regulation.

Cluster C personality disorders Personality disorders characterized by anxious or fearful behaviors.

| Prevalence |

|

| Comorbidity |

|

| Onset |

|

| Course |

|

| Gender Differences |

|

| Source: Unless otherwise noted, American Psychiatric Association, 2000. |

In the subsequent discussions of individual personality disorders, you may notice that adding the prevalence rates for the various disorders gives a higher total than the overall prevalence rate of 14% listed in TABLE 13.2 on the next page. This mathematical discrepancy is explained by the high comorbidity, also noted in the table: Half of people who have a personality disorder will be diagnosed with at least one other personality disorder (and, in some cases, with more than one other personality disorder).

Criticisms of the DSM-5 Category of Personality Disorders

The category of personality disorders, as defined in DSM-5 (and in DSM-IV), has been criticized on numerous grounds. One criticism is that DSM-5 treats personality disorders as categorically distinct from normal personality (Widiger & Lowe, 2008). In contrast, most psychological researchers currently view normal personality and personality disorders as being on continua. In DSM-5 terms, two people might differ only slightly in the degree to which they exhibit a personality trait, but one person would be considered to have a personality disorder and the other person would not. A related criticism is that the DSM-5 criteria for personality disorders create an arbitrary cutoff on the continuum between normal and abnormal (Morey et al., 2012; Widiger & Trull, 2007). In part to address this point, newly created for DSM-5 is an alternative model of personality disorders that allows mental health professionals to rate how impaired patients are in terms of various dimensions (American Psychiatric Association, 2013).

406

Another criticism pertains to the clusters, which were organized by superficial commonalities. Research does not necessarily support the organization of personality disorders into these clusters (Sheets & Craighead, 2007). Moreover, some of the specific personality disorders are not clearly distinct from each other (Trull et al., 2012).

In addition, some personality disorders are not clearly distinct from other disorders in DSM (Harford et al., 2013; Widiger & Trull, 2007). The diagnostic criteria for avoidant personality disorder, for example, overlap considerably with those for social phobia, as we’ll discuss in the section on avoidant personality disorder. Similarly, critics point out that the general criteria for personality disorders (see TABLE 13.1) could apply to other disorders, such as persistent depressive disorder and schizophrenia (Oldham, 2005).

The process by which the DSM-IV/DSM-5 criteria were determined is another target of criticism. The minimum number of symptoms needed to make a diagnosis, as well as the specific criteria, aren’t necessarily supported by research results (Widiger & Trull, 2007). Moreover, different personality disorders require different numbers of symptoms and different levels of impairment (Livesley, 2001; Skodol, 2005; Westen & Shedler, 2000).

The high comorbidity among personality disorders invites another criticism: that the specific personality disorders do not capture the appropriate underlying problems, and so clinicians must use more than one diagnosis to describe the types of problems exhibited by patients (Widiger & Mullins-Sweatt, 2005). In fact, the most frequently diagnosed personality disorder is a nonspecific personality disorder that we’ll call other personality disorder in this chapter; this disorder is often diagnosed along with an additional personality disorder (Hopwood et al., 2012; Verheul et al., 2007; Verheul & Widiger, 2004). As with other categories of disorders, the nonspecific “other” diagnosis is used when a patient’s symptoms cause distress or impair functioning but do not fit the criteria for any of the disorders within the relevant category—in this case, one of the 10 specific personality disorders.

Understanding Personality Disorders in General

At one point, Reiland became impatient with her 4-year-old son Jeffrey and “lost it.” She slapped and then cursed him. As he cried, she commanded him to stop crying. He didn’t, and she proceeded to spank him so hard that it hurt her hand:

The reality slowly sunk in. I had beaten my child. Just as my father had beaten his. Just as I swore I never ever would. A wave of nausea rose within me. I was just like my father. Even my children would be better off without me. There was no longer any reason to stay alive.

(Reiland, 2004, p. 19)

Reiland’s realization was relatively unusual for someone with a personality disorder: She recognized in this instance that she had created a problem—she had done something wrong, although her father never recognized his responsibility. He too was quick to anger and hit her and her siblings. Do personality disorders run in families? If so, to what extent do genes and environment lead to personality disorders? How might personality disorders arise?

407

Neurological Factors in Personality Disorders: Genes and Temperament

GETTING THE PICTURE

Lisa Peardon/Getty Images

Perhaps the most influential neurological factor associated with personality disorders is genes (Cloninger, 2005; Paris, 2005). Researchers have not produced evidence that genes underlie specific personality disorders, but they have shown that genes clearly influence temperament, which is the aspect of personality that reflects a person’s typical affective state and emotional reactivity (see Chapter 2). Temperament, in turn, plays a major role in personality disorders. Genes influence temperament via their effects on brain structure and function, including neurotransmitter activity.

It is possible that the genes that affect personality traits can predispose some people to develop a personality disorder (South & DeYoung, 2013). For instance, some people are genetically predisposed to seek out novel and exciting stimuli, such as those associated with stock trading, race car driving, or bungee jumping, whereas other people are predisposed to become easily overstimulated and habitually prefer low-key, quiet activities, such as reading, writing, or walking in the woods. Such differences in temperament are the foundation on which different personality traits are built—and, at their extremes, temperaments can give rise to inflexible personality traits that are associated with personality disorders. Examples include a novelty seeker (temperament) who compulsively seeks out ever more exciting activities (inflexible behavior pattern), regardless of the consequences, and a person who avoids overstimulation (temperament) and turns down promotions because the new position would require too many activities that would be overstimulating (inflexible behavior pattern).

Reiland may well have inherited a tendency to develop certain aspects of temperament, which increased the likelihood of her behaving like her father in certain types of situations. However, her genes and her temperament don’t paint the whole picture; psychological and social factors also influenced how she thought, felt, and behaved.

408

Psychological Factors in Personality Disorders: Temperament and the Consequences of Behavior

Although an infant may be born with a genetic bias to develop certain temperamental characteristics, these characteristics—and personality traits—evolve through experience in interacting with the world. Personality traits involve sets of learned behaviors and emotional reactions to specific stimuli; what is learned is in part shaped by the consequences of behavior, including how other people respond to the behavior. The mechanisms of operant conditioning are at work whenever a person experiences consequences of behaving in a certain way: If the consequences are positive, the behavior is reinforced (and hence likely to recur); if the consequences are negative, the behavior is punished (and hence likely to be dampened down).

The consequences of behaving in a specific way not only affect how temperament develops but also influence a person’s expectations, views of others, and views of self (Bandura, 1986; Farmer & Nelson-Gray, 2005). Based on what they have learned, people can develop maladaptive and faulty beliefs, which in turn lead them to misinterpret other people’s words and actions. These (mis)interpretations reinforce their views of themselves and the world in a pervasive self-fulfilling cycle, biasing what they pay attention to and remember, which in turn reinforces their views of self and others (Beck et al., 2004; Linehan, 1993; Pretzer & Beck, 2005). The consequences of behavior can thereby lead to pervasive dysfunctional beliefs—which can form the foundation for some types of personality disorders. For instance, at one point Rachel Reiland states her belief that her husband “doesn’t deserve me—no one should have to put up with me!” (Reiland, 2004. This belief leads her to be hypervigilant for any annoyance her husband expresses or implies. She’s likely to misinterpret his actions and comments as confirming her belief that she is undeserving, and she then alternates lashing out in anger with groveling in grief.

Social Factors in Personality Disorders: Insecurely Attached

Another factor that influences whether a person will develop a personality disorder is attachment style—the child’s emotional bond and way of interacting with (and thinking about) his or her primary caretaker (Bowlby, 1969; see Chapter 1). The attachment style established during childhood often continues into adulthood, affecting how the person relates to others (Waller & Shaver, 1994). Most children develop a secure attachment style (Schmitt et al., 2004), which is characterized by a positive view of their own worth and of the availability of others. However, a significant minority of children develop an insecure attachment style, which can involve a negative view of their own worth, the expectation that others will be unavailable, or both (Bretherton, 1991). People with personality disorders are more likely to have an insecure attachment style (Crawford et al., 2006; Lahti et al., 2012).

People can develop an insecure attachment style for a variety of reasons, such as childhood abuse (sexual, physical, or verbal), neglect, or inconsistent discipline (Johnson et al., 2005; Johnson, Cohen, et al., 2006; Paris, 2001). Reiland’s father abused her physically and verbally, alternating the abuse with bouts of neglect. However, such social risk factors may lead to psychopathology in general, not personality disorders in particular (Kendler et al., 2000). A single traumatic event does not generally lead to a personality disorder (Rutter, 1999).

Feedback Loops in Understanding Personality Disorders

ONLINE

As with other kinds of psychological disorders, no one factor reigns supreme as the underlying basis of personality disorders. People must have several adverse factors—neurological, psychological, or social—to develop a personality disorder, and social adversity will have the biggest effect on those who are neurologically vulnerable (Paris, 2005).

409

Consider the fact that people with personality disorders tend to have parents with psychological disorders (Bandelow et al., 2005; Siever & Davis, 1991). The parents’ dysfunctional behavior clearly creates a stressful social environment for children, and the children may model some of their parents’ behavior (psychological factor). Moreover, they may also inherit a predisposition toward a specific temperament (neurological factor). Similarly, chronic stress and abuse, such as Reiland experienced, affects brain structure and function (neurological factor; Teicher et al., 2003), which in turn affects mental processes (psychological factor).

The specific personality disorder a person develops depends on his or her temperament and family members’ reactions to that temperament (Linehan, 1993; Rutter & Maughan, 1997). For instance, children with difficult temperaments—such as those that lead a person to be extremely passive—tend to have more conflict with their parents and peers (Millon, 1981; Rutter & Quinton, 1984), which leads them to experience a higher incidence of physical abuse and social rejection. These children may then come to expect (psychological factor) to be treated poorly by others (social factor). Thus, social factors can amplify underlying temperaments and traits so that they subsequently form the foundation for a personality disorder (Caspi et al., 2002; Paris, 1996, 2005).

Treating Personality Disorders: General Issues

People with disorders other than personality disorders often say that their problems “happened” to them—the problems are overlaid on their “usual” self. They want the problems to get better so that they can go back to being that usual self, and thus they seek treatment. In contrast, people with personality disorders don’t see the problem as overlaid on their usual self; by its very nature, a personality disorder is integral to the way such people function in the world. And so people with these disorders are less likely to seek treatment unless they also have another type of disorder—in which case, they typically seek help for the other disorder.

Addressing and reducing the symptoms of a personality disorder can be challenging because patients’ entrenched maladaptive beliefs and behaviors can lead them to be poorly motivated during treatment and not inclined to collaborate with the therapist. Treatment for personality disorders generally lasts longer than does treatment for other psychological disorders. However, there is little research on treatment for most personality disorders. The next section summarizes what is known about treating personality disorders in general; later in the chapter we discuss treatments for the specific personality disorders for which there are substantial research results.

Targeting Neurological Factors in Personality Disorders

Treatments for personality disorders that target neurological factors include antipsychotics, antidepressants, mood stabilizers, or other medications. Generally, however, such medications are only effective for symptoms of certain other disorders (such as anxiety) and are not very helpful for symptoms of personality disorders per se (Paris, 2005, 2008). Nevertheless, some of these medications may reduce temporarily some symptoms (Paris, 2003; Soloff, 2000).

Targeting Psychological Factors in Personality Disorders

Both cognitive-behavior therapy (CBT) and psychodynamic therapy have been used to treat personality disorders. Both therapies focus on core issues that are theorized to give rise to the disorders; they differ in terms of the inferred core issues. Psychodynamic therapy addresses unconscious drives and motivations, whereas CBT addresses maladaptive views of self and others and negative beliefs that give rise to the problematic feelings, thoughts, and behaviors of the personality disorder (Beck et al., 2004). CBT is intended to increase the patient’s sense of self-efficacy and mastery and to modify the negative, unrealistic beliefs that lead to maladaptive behaviors.

410

In addition, because people with personality disorders may not be motivated to address the problems associated with the disorder, treatment may employ motivational enhancement strategies to help patients identify goals and become willing to work with the therapist. Treatment that targets psychological factors has been studied in depth only for borderline personality disorder; we examine such treatment in the section discussing that personality disorder.

Targeting Social Factors in Personality Disorders

Guidelines for treating personality disorders also stress the importance of the relationship between therapist and patient, who must collaborate on the goals and methods of therapy (Critchfield & Benjamin, 2006). In fact, the relationship between patient and therapist may often become a focus of treatment as the patient’s typical style of interacting with others plays out in the therapy relationship. This relationship often provides an opportunity for the patient to become aware of his or her interaction style and to develop new ways to interact with others (Beck et al., 2004).

In addition, family education, family therapy, or couples therapy can provide a forum for family members to learn about the patient’s personality disorder and to receive practical advice about how to help the patient—for example, how to respond when the patient gets agitated or upset. Family therapy can provide support for families as they strive to change their responses to the patient’s behavior, thereby changing the reinforcement contingencies (Ruiz-Sancho et al., 2001).

Moreover, interpersonal or group therapy can highlight and address the maladaptive ways in which patients relate to others. Therapy groups also provide a forum for patients to try out new ways of interacting (Piper & Ogrodniczuk, 2005). For example, if a man thinks and acts as if he is better than others, the comments and responses of other group members can help him understand how his haughty and condescending way of interacting creates problems for him.

Thinking Like A Clinician

V.J. was 50 years old, never married, and had never been very successful professionally. He was a salesman and changed companies every few years, either because he was passed over for a promotion and quit or because he didn’t like the new rules—or the way that the rules were enforced—at the job. He’d been in love a few times, but it had never worked out. He chalked it up to difficulty finding the right woman. He had some “friends” who were really people he’d known over the years and saw occasionally. Most of his positive social interactionshappened in chat rooms or texts.

Is there anything about the information presented that would lead you to wonder whether V.J. might have a personality disorder? If so, what was the information? (And if not, why not?) Based on what you have read, how should mental health clinicians go about determining whether V.J. might have a personality disorder or whether his personality traits are in the normal range?