14.4 Disorders of Disruptive Behavior and Attention

In addition to Javier Enriquez’s apparent difficulties reading, his teacher has commented—not very positively—on Javier’s high energy level. He doesn’t always stay in his chair during class, and when he’s working on a group project, other kids seem to get annoyed at him: “He can get ‘in their face’ a bit.” Javier’s mother, Lela, and his father, Carlos, acknowledge that Javier is a very active, energetic boy. But Carlos says, “I was that way when I was a kid, but I grew out of it as I got older.” Javier’s teacher recently mentioned the possibility of his having attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.

In contrast, Javier’s sister, 8-year-old Pia, is definitely not energetic. Like her brother, Pia is clearly bright, but her teacher says she seems to “space out” in class. The teacher thinks that Pia simply does not apply herself, but her parents wonder whether she’s underachieving because she’s bored and understimulated in school. At home, Pia has defied her parents increasingly often—not doing her chores or performing simple tasks they ask her to do. At other times, Pia is off in her own world, “kind of like an absent-minded professor.” Is Pia’s behavior in the normal range, or does it signal a problem? If so, what might the problem be?

And what about Javier’s behavior—is it in the normal range? Most children are disruptive some of the time. But in some cases, the disruptive behavior is much more frequent and obtrusive and becomes a cause for concern. Even if disruptive behaviors do not distress the children who perform them, they often distress other people or violate social norms (Christophersen & Mortweet, 2001). The most common reason that children are referred to a mental health clinician is because they engage in disruptive behavior at home, at school, or both (Frick & Silverthorn, 2001). The clinician must distinguish between normal behavior and pathologically disruptive behavior and, if the behavior falls outside the normal range, determine which disorder(s) might be the cause.

Three disorders are associated with disruptive behavior: conduct disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, and attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder (which is characterized mainly by problems with attention but sometimes by disruptive behavior as well). Although DSM-5 does not put attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in the category of disruptive disorders (but rather puts it in category of neurodevelopmental disorders), we discuss it here both because the symptoms can include disruptive behavior and because symptoms of these three disorders commonly—though not always—occur together.

460

What Is Conduct Disorder?

Conduct disorder A psychological disorder that typically arises in childhood and is characterized by the violation of the basic rights of others or of societal norms that are appropriate to the person’s age

The hallmark of conduct disorder is a violation of the basic rights of others or of societal norms that are appropriate to the person’s age (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). As outlined in TABLE 14.8, 15 types of behaviors are listed in the diagnostic criteria for conduct disorder; these behaviors are sorted into four categories.

|

| Reprinted with permission from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, (Copyright ©2013). American Psychiatric Association. All Rights Reserved. |

DSM-5 requires the presence of at least 3 out of the 15 types of behavior within the past 12 months and at least 1 type of such behavior must have occurred during the past 6 months. Although the diagnosis requires impaired functioning in some area of life, it does not require distress.

Just as the criteria for antisocial personality disorder (Chapter 13) focus almost exclusively on behavior that violates the rights of others, so do the criteria for conduct disorder. However, people diagnosed with conduct disorder also often have outbursts of anger, recklessness, and poor frustration tolerance. Most people diagnosed with conduct disorder are under 18 years old; if the behaviors persist into adulthood, the person usually meets the criteria for antisocial personality disorder.

Like people with antisocial personality disorder, people with conduct disorder appear to lack empathy and concern for others, and they don’t exhibit genuine remorse for their misdeeds. In fact, when the intent of another person’s behavior is ambiguous, a person with conduct disorder is likely to misconstrue the other’s motives as threatening or hostile and then feel justified in his or her own aggressive behavior. People with conduct disorder typically blame others for their inappropriate behaviors (“He made me do it”).

461

DSM-5 specifies three levels of intensity for the symptoms of conduct disorder: mild (few behaviors or causing minimal harm), moderate, and severe (many behaviors or causing significant harm). Symptoms may progress from mildly disruptive to severely disruptive.

People with conduct disorder are also likely to use—and abuse—substances at an earlier age than are people without this disorder. Similarly, they are more likely to have problems in school (such as suspension or expulsion), legal problems, unplanned pregnancies and sexually transmitted diseases, and physical injuries that result from fights. Because of their behavioral problems, children with conduct disorder may live in foster homes or attend special schools. They may also have poor academic achievement and score lower than normal on verbal intelligence tests. Problems with relationships, financial woes, and other psychological disorders may persist into adulthood (Colman et al., 2009).

When clinicians assess whether conduct disorder might be an appropriate diagnosis for a person, they will of course talk with him or her; however, the nature of conduct disorder is such that a child or an adult patient may not provide complete information about his or her behavior. Thus, when diagnosing a child, clinicians try to obtain additional information from other sources, usually school officials or parents, although even these people may not know the full extent of a child’s conduct problems. By the same token, when diagnosing adults, clinicians try to obtain additional information from family members, peers, or coworkers. Usually, the behaviors that characterize conduct disorder are not limited to one setting but occur in a variety of settings: in school or work, at home, in the neighborhood. This was true for Brad, as described in Case 14.4.

CASE 14.4 • FROM THE OUTSIDE: Conduct Disorder

Brad was [a teenager and] small for his age but big on fighting. For him, this had gone beyond schoolyard bullying. He had four assault charges during the previous 6 months, including threatening rape and beating up a much younger boy who was mentally challenged. The family was being asked to leave their apartment complex because of Brad’s aggressive behavior and several stealing incidents. Other official arrests included burglaries and trespassing. Brad had participated in a number of outpatient services, including anger management classes in which he had done well, but obviously he was not applying what he had learned to everyday life. He was referred to [a treatment] program by the juvenile court judge.

Prior to placement, Brad had lived with his mother and older brother. Their family life had been characterized by many disruptions, including contact with several abusive father figures and frequent moves. Brad’s older brother also had a record with the juvenile authorities, but his offenses were confined to property crimes and the use of alcohol. He had graduated from an inpatient substance abuse program. Brad and his brother had a history of physical fighting. Prior to the boys’ births, Mrs. B had had two children removed from her custody by state protective services. Mrs. B was very protective of Brad. She felt that the police and schools had it “in for him” and regularly defended him as having been provoked or blamed falsely. Although she was devastated at having Brad removed from her home, Mrs. B reported that she could no longer deal with Brad’s aggression.

(Chamberlain, 1996, pp. 485–486)

DSM-5 uses the timing of onset to define two types of conduct disorder, which typically have different courses and prognoses:

- adolescent-onset type, in which no symptoms were present before age 10; and

- childhood-onset type, which is more severe and in which the first symptoms appeared when the child was younger than 10 years old.

462

As noted in TABLE 14.9, various characteristics of conduct disorder that develop in childhood are different from those of the conduct disorder that develops in adolescence. In the following sections we examine them in more detail.

| Prevalence |

|

| Onset |

|

| Comorbidity |

|

| Course |

|

| Gender Differences |

|

| Source: Unless otherwise noted, the source for information is American Psychiatric Association, 2013. |

Adolescent-Onset Type

For people with adolescent-onset type, the symptoms of conduct disorder emerge after—but not before—puberty, considered in DSM-5 to occur at 10 years of age. The disruptive behaviors are not likely to be violent and typically include minor theft, public drunkenness, and property offenses rather than violence against people and robbery, which are more likely with childhood-onset type (Moffitt et al., 2002). The behaviors associated with adolescent-onset type conduct disorder can be thought of as exaggerations of normal adolescent behaviors (Moffitt & Caspi, 2001). With this type, the disruptive behaviors are usually transient, and adolescents with this disorder are able to maintain relationships with peers. This type of conduct disorder has been found to have a small sex difference; the male to female ratio is 1.5 to 1 (Moffitt & Caspi, 2001).

Childhood-Onset Type

Research has shown that people with the childhood-onset type of conduct disorder can be further divided into two categories: Those who are callous and/or unemotional (Caputo et al., 1999; Frick et al., 2000), which are features of psychopathy (discussed in Chapter 13), and those who are not.

Childhood-Onset Type, Neither Callous nor Unemotional

People with childhood-onset conduct disorder who are not callous and display feelings of guilt or remorse for their deeds are less likely to be aggressive in general; when they are aggressive, it is usually as a reaction to a perceived or real threat—it is not premeditated (Frick et al., 2003). People with this sort of conduct disorder have difficulty regulating their negative emotions: They have high levels of emotional distress (Frick & Morris, 2004; Frick et al., 2003), and they react more strongly to other people’s distress and to negative emotional stimuli generally (Loney et al., 2003; Pardini et al., 2003).

In addition, such people process social cues less accurately than normal and so are more likely to misperceive such cues and respond aggressively when (mis)perceiving threats (Dodge & Pettit, 2003). Because of their problems in regulating negative emotions, they are more likely to act aggressively and antisocially in impulsive ways when distressed. They often feel bad afterward but still can’t control their behavior (Pardini et al., 2003). Children with this disorder may fall into a negative interaction pattern with their parents: When a parent brings up the child’s past or present misconduct, the child becomes agitated and then doesn’t appropriately process what the parent says, becomes more distressed, and impulsively behaves in an aggressive manner. The parent may respond with aggression (verbal or physical), creating a vicious cycle (Gauvain & Fagot, 1995).

463

Childhood-Onset Type, With Callous and Unemotional Traits

Although not consider a “subtype” in DSM-5, the manual allows mental health professionals to specify when someone with childhood-onset conduct disorder has callous and unemotional features (specified in DSM-5 as with limited prosocial emotions). This group of people has some unique characteristics: Like adults with psychopathy, these young people seek out exciting and dangerous activities, are relatively insensitive to threat of punishment, and are strongly oriented toward the possibility of reward (Frick et al., 2003; Pardini et al., 2003). Moreover, they react less strongly to threatening or distressing stimuli (Frick et al., 2003; Loney et al., 2003).

Researchers propose that the decreased sensitivity to punishment—associated with low levels of fear—underlies the unique constellation of callousness and increased aggression (Frick, 2006; Pardini et al., 2006). People with this sort of conduct disorder are not concerned about the negative consequences of their violent behaviors. And being insensitive to punishment, they don’t learn to refrain from certain behaviors and thereby fail to internalize social norms or develop a conscience or empathy for others (Frick & Morris, 2004; Pardini, 2006; Pardini et al., 2003). In fact, people with conduct disorder with callous and unemotional traits are less likely to recognize emotional expressions of sadness (Blair et al., 2001). This variant of conduct disorder has the highest heritability and is associated with more severe symptoms (Viding et al., 2005).

What Is Oppositional Defiant Disorder?

Oppositional defiant disorder A disorder that typically arises in childhood or adolescence and is characterized by angry or irritable mood, defiance or argumentative behavior, or vindictiveness.

The defining characteristics of oppositional defiant disorder are angry or irritable mood, defiance or argumentative behavior, or vindictiveness. As noted in TABLE 14.10, for a diagnosis of oppositional defiant disorder, DSM-5 requires that the person exhibit four out of eight symptoms, many of which are confrontational behaviors, such as arguing with authority figures, intentionally annoying others, and directly refusing to comply with an authority figure’s or adult’s request, which were true of Josh, in Case 14.5. (However, according to DSM-5, such behavior with a sibling is not grounds for diagnosing the disorder.) Young children with oppositional defiant disorder may have intense and frequent temper tantrums. Pia did not comply with her parents’ requests to complete her chores or help with other tasks; her teacher has commented on a similar behavior pattern at school.

|

| Reprinted with permission from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, (Copyright ©2013). American Psychiatric Association. All Rights Reserved. |

These behaviors must have occurred for at least 6 months, more frequently than would be expected for the person’s age and developmental level, and must impair functioning.

CASE 14.5 • FROM THE OUTSIDE: Oppositional Defiant Disorder

At school and with friends, Josh behaves like a perfectly normal ten-year-old boy. At home, however, it’s a very different story. Josh pushes every limit possible. He often swears at his parents and harasses his siblings. Forget about asking Josh to do things around the house—he refuses to do even the most routine chores without serious resistance toward his parents. Communication between Josh and his parents consists of a series of arguments, leaving them all exhausted, angry, and tense.

(Bernstein, 2006, p. 2)

464

The disruptive behaviors of oppositional defiant disorder are different in several important ways from those characterizing conduct disorder. Oppositional defiant disorder involves only a subset of the symptoms of conduct disorder—the overtly defiant behaviors—and these are often verbal. The disruptive behaviors of oppositional defiant disorder are:

- generally directed toward authority figures;

- not usually violent and do not usually cause severe harm; and

- in children, often exhibited only in specific situations with parents or other adults the children know well (Christophersen & Mortweet, 2001).

The clinician must obtain information from others when assessing disruptive behaviors and must keep in mind any cultural factors that might influence which sorts of behaviors are deemed acceptable or unacceptable.

According to DSM-5, if a person meets the diagnostic criteria for both oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder, both disorders would be diagnosed. TABLE 14.11 lists additional facts about oppositional defiant disorder.

| Prevalence |

|

| Onset |

|

| Comorbidity |

|

| Course |

|

| Gender Differences |

|

| Cultural Differences |

|

| Source: Unless otherwise noted, the source for information is American Psychiatric Association, 2013. |

What Is Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder?

Attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) A disorder that typically arises in childhood and is characterized by inattention, hyperactivity, and/or impulsivity.

People who have oppositional defiant disorder or conduct disorder intend to defy rules, authority figures, or social norms, and hence behave disruptively. But people may unintentionally behave disruptively because they have another disorder, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), which is characterized by six or more symptoms of inattention, hyperactivity, and/or impulsivity (five or more in people 17 years old or greater). People diagnosed with this disorder vary in which set of symptoms is most dominant; some primarily have difficulty maintaining attention, whereas others primarily have difficulty with hyperactivity and impulsivity. Still others have all three types of symptoms. To meet the criteria for the diagnosis (see TABLE 14.12), the symptoms must impair functioning in at least two settings, such as at school and at work or at work and at home, and some symptoms must have been present by age 12. The impulsivity and hyperactivity are most noticeable and disruptive in a classroom setting. Javier’s difficulty staying in his chair at school, which disrupted the class, may have reflected this disorder. In Case 14.6, an adult recounts how he recognized his own ADHD.

|

| Reprinted with permission from the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition, (Copyright ©2013). American Psychiatric Association. All Rights Reserved. |

465

466

CASE 14.6 • FROM THE INSIDE: Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder

Attention-deficit disorder (ADD) was the term used in the third edition of the DSM. In his book Driven to Distraction: Recognizing and Coping with Attention Deficit Disorder from Childhood Through Adulthood, psychiatrist Edward Hallowell recounts what happened when he learned about the disorder:

I discovered I had ADD when I was thirty-one years old, near the end of my training in child psychiatry at the Massachusetts Mental Health Center in Boston. As my teacher in neuropsychiatry began to describe ADD in a series of morning lectures during a steamy Boston summer, I had one of the great “Aha!” experiences of my life.

“There are some children,” she said, “who chronically daydream. They are often very bright, but they have trouble attending to any one topic for very long. They are full of energy and have trouble staying put. They can be quite impulsive in saying or doing whatever comes to mind, and they find distractions impossible to resist.”

So there’s a name for what I am! I thought to myself with relief and mounting excitement. There’s a term for it, a diagnosis, an actual condition, when all along I’d thought I was just slightly daft…. I wasn’t all the names I’d been called in grade school—“a daydreamer,” “lazy,” “an underachiever,” “a spaceshot”—and I didn’t have some repressed unconscious conflict that made me impatient and action-oriented.

What I had was an inherited neurological syndrome characterized by easy distractibility, low tolerance for frustration or boredom, a greater-than-average tendency to say or do whatever came to mind…and a predilection for situations of high intensity. Most of all, I had a name for the overflow of energy I so often felt—the highly charged, psyched-up feeling that infused many of my waking hours in both formative and frustrating ways.

(Hallowell & Ratey, 1994, pp. ix–x)

Symptoms of hyperactivity may be different in females than in males: Girls who have hyperactive symptoms may talk more than other girls or may be more emotionally reactive, rather than hyperactive with their bodies (Quinn, 2005). Some researchers propose that ADHD is underdiagnosed in girls, who are less likely to have behavioral problems at school and so are less likely to be referred for evaluation (Quinn, 2005). In fact, female teenagers with ADHD are likely to be diagnosed with and treated for depression before the ADHD is diagnosed (Harris International, 2002, cited in Quinn, 2005).

Because the sets of symptoms of ADHD vary, clinicians find it useful to classify ADHD into different forms (“presentations” to use the DSM-5 term). The predominantly hyperactive/impulsive form is associated with disruptive behaviors, accidents, and rejection by peers, whereas the inattentive form of ADHD is associated with academic problems that are typical of deficits in executive functions: difficulty remembering a sequence of behaviors, monitoring and shifting the direction of attention, organizing material to be memorized, and inhibiting interference during recall. Some patients may have a combination of the two types of symptoms.

However, symptoms may change over time; as some children get older, the particular set of symptoms they exhibit can shift, most frequently from hyperactive/impulsive to the type that has a combination of the two sets of symptoms (Lahey, Pelham, et al., 2005). Children with ADHD often have little tolerance for frustration, as was true of Edward Hallowell in Case 14.6; such children tend to have temper outbursts, changeable moods, and symptoms of depression. Once properly diagnosed and treated, such symptoms often decrease.

Problems with attention are likely to become more severe in group settings, where the person receives less attention or rewards, in settings when sustained attention is necessary, or when a task is thought to be boring—which is what happened to Javier. Various psychological and social factors can reduce symptoms, including:

467

- frequent rewards for appropriate behavior;

- close supervision;

- being in a new situation or setting;

- doing something interesting; and

- having someone else’s undivided attention.

Socially, people with ADHD may initiate frequent shifts in the topic of a conversation, either because they are not paying consistent attention to the conversation or because they are not following implicit social rules. People with symptoms of hyperactivity may talk so much that others can’t get a word in edgewise, or they may inappropriately start conversations. These symptoms can make peer relationships difficult. In addition, symptoms of impulsivity can lead to increased risk of harm. As the child heads into adulthood, hyperactive and impulsive symptoms tend to decrease but not disappear. Symptoms of inattention, however, do not tend to decrease as much. Additional facts about ADHD are presented in TABLE 14.13.

| Prevalence |

|

| Comorbidity |

|

| Onset |

|

| Course |

|

| Gender Differences |

|

| Cultural Differences |

|

| Source: Unless otherwise noted, the source for information is American Psychiatric Association, 2000. |

468

Understanding Disorders of Disruptive Behavior and Attention

Given the high comorbidity and overlap of symptoms among the three disorders—conduct disorder, oppositional defiant disorder, and ADHD—we’ll focus on the disorder that is best understood, ADHD. Studies of factors related to oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder probably include participants who also have ADHD, which makes it difficult to determine which factors are uniquely associated with oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder and not ADHD.

Neurological Factors

Research has revealed that people who have ADHD have abnormal brain structure and function, and research also has begun to characterize the roles of neurotransmitters and genes in these brain abnormalities.

ADHD: Brain Systems and Neural Communication

The behavioral problems that characterize people with ADHD may arise in part from impaired frontal lobe functioning. This hypothesis is consistent with the fact that people with ADHD often cannot perform functions well that rely on the frontal lobes, such as various executive functions (e.g., formulating and following plans; Kiliç et al., 2007) and estimating time accurately, which affects their ability to plan and follow through on commitments (Barkley et al., 2001; McInerney & Kerns, 2003; Riccio et al., 2005).

Studies have shown that children and adolescents with this disorder have smaller brains than do children and adolescents without the disorder, and the deficit in size is particularly marked in the frontal lobes (Schneider, Retz et al., 2006; Sowell et al., 2003; Valera et al., 2007). Indeed, particular parts of the frontal lobes have been shown to be relatively small in adults with ADHD (Durston et al., 2004; Hesslinger et al., 2002).

Although research findings implicate the frontal lobes, they also indicate that it is not the sole culprit that underlies ADHD. In particular, people with ADHD also have smaller cerebellums, which is noteworthy because this brain structure is crucial to attention and timing; in fact, the smaller this structure, the worse the symptoms of ADHD are (Castellanos et al., 2002; Mackie et al., 2007).

Studies have also shown that ADHD is not a result of impaired functioning in any single brain area but rather emerges from how different areas interact. Neuroimaging studies have revealed many patterns of abnormal brain functioning in people who have ADHD (Rubia et al., 2007; Stevens et al., 2007; Vance et al., 2007). In general, neural structures involved in attention tend not to be activated as strongly (during relevant tasks) in people with this disorder as in people without it (Stevens et al., 2007; Schneider, Retz, et al., 2006; Vance et al., 2007). However, virtually every lobe in the brains of people with ADHD has been shown not to function normally during tasks that draw on their functions (Mulas et al., 2006; Vance et al., 2007).

Moreover, abnormal brain functioning can influence the autonomic nervous system (see Chapter 2): ADHD (and some types of conduct disorder) has been associated with unusually low arousal in response to normal levels of stimulation (Crowell et al., 2006), a response that could explain some of the stimulation-seeking behavior seen in people with this disorder. That is, these people could engage in stimulation-seeking behavior in order to obtain an optimal level of arousal.

People with ADHD have lower-than-normal levels of dopamine—which is a key neurotransmitter used in the frontal lobes and in many other brain areas. However, the overall pattern of difficulties that characterizes ADHD suggests problems with multiple neurotransmitters—including serotonin and norepinephrine—that are involved in coordinating and organizing cognition and behavior (Arnsten, 2006; Volkow et al., 2007). Given the number of brain areas that are involved, problems with multiple neurotransmitters are probably associated with the disorder.

469

ADHD and Genetics

Genes may be one reason why people with ADHD have abnormal brain systems and disrupted neural communication. Indeed, not only does this disorder run in families, but also parent and teacher reports indicate that it is highly correlated among monozygotic twins (with correlations ranging from 0.60 to 0.90). In addition, a large set of data reveals that this disorder is among the most heritable of psychological disorders (Martin et al., 2006; Stevenson et al., 2005; Waldman & Gizer, 2006).

However, as with most other psychological disorders that are influenced by genes, a combination of genes—not a single gene—probably contributes to it (Faraone et al., 2005). In fact, over a dozen different genes have so far been identified as possibly contributing to this disorder (Guan et al., 2009; Swanson et al., 2007; Waldman & Gizer, 2006).

Moreover, as usual, genes are not destiny: The effects of the genes depend in part on the environment. For example, children whose mothers smoked while pregnant are much more likely to develop ADHD than are children whose mothers did not smoke (Braun et al., 2006), and this relationship appears to be particularly strong for children who have a specific gene (Neuman et al., 2007).

Psychological Factors: Recognizing Facial Expressions, Low Self-Esteem

In addition to problems with attention and executive function, people with ADHD may have other, perhaps less obvious, difficulties. In particular, as with ASD, people with ADHD have difficulty recognizing emotions in facial expressions (Demopoulos et al., 2013)—but not all emotions; they have problems recognizing anger and sadness in particular. Why? The answer isn’t known, but one suggestion is that these people might have had very negative experiences with others who are sad or angry, and these unpleasant experiences motivate them to tune out such expressions (Pelc et al., 2006).

In addition, children with ADHD appear to have an attributional style that leaves them vulnerable to low self-esteem. In one study (Milich, 1994), children with ADHD initially overestimated their ability to succeed in a challenging task, and—when confronted with failure—boys with ADHD became more frustrated and were less likely to persist with the challenging task than were boys in a control group. Moreover, in another study (Collett & Gimpel, 2004), children with ADHD attributed the cause of negative events to global and stable characteristics about themselves (“I am a failure”) rather than external, situational factors (“That was a very hard task”). Conversely, children with ADHD were more likely than children without a psychological disorder to attribute positive events to external, situational causes. These attribution patterns were observed regardless of whether children were taking medication for ADHD. Such patterns are often seen in people who experience low self-esteem (Sweeney et al., 1986; Tennen & Herzberger, 1987).

Low self-esteem among those with ADHD isn’t restricted to children. One study compared college students with and without ADHD and matched them to control participants who had comparable demographic variables and grade-point averages. Students with ADHD reported lower self-esteem and social skills than did students without ADHD (Shaw-Zirt et al., 2005). Other studies report lower self-esteem among adolescents with ADHD (Slomkowski et al., 1995).

Social Factors: Blame and Credit

The low self-esteem of children with ADHD may also be related to social factors, in particular to their parents’ attributions: Although parents don’t necessarily blame their children for ADHD-related behaviors, they don’t give their children as much credit for positive behaviors as do parents of children without ADHD (Johnston & Freeman, 1997). The parents of children with ADHD tend to attribute children’s positive behaviors to random situational factors.

470

In addition, social factors can indirectly influence the development of this disorder. For example, children typically are raised in homes selected by their parents—based on various social factors, such as parents’ financial status, proximity to extended family, and community resources. If children are raised in a house where lead paint has been applied, they may be more vulnerable to ADHD. In fact, children whose hair contains higher levels of lead (which is a measure of exposure to lead, perhaps from lead paint in one’s home environment) are more likely to have ADHD than are children who have lower levels of lead in their hair (Tuthill, 1996). Even children who were exposed to very low levels of lead in their environment are more likely to develop ADHD than are children who were not exposed (Nigg, 2006b).

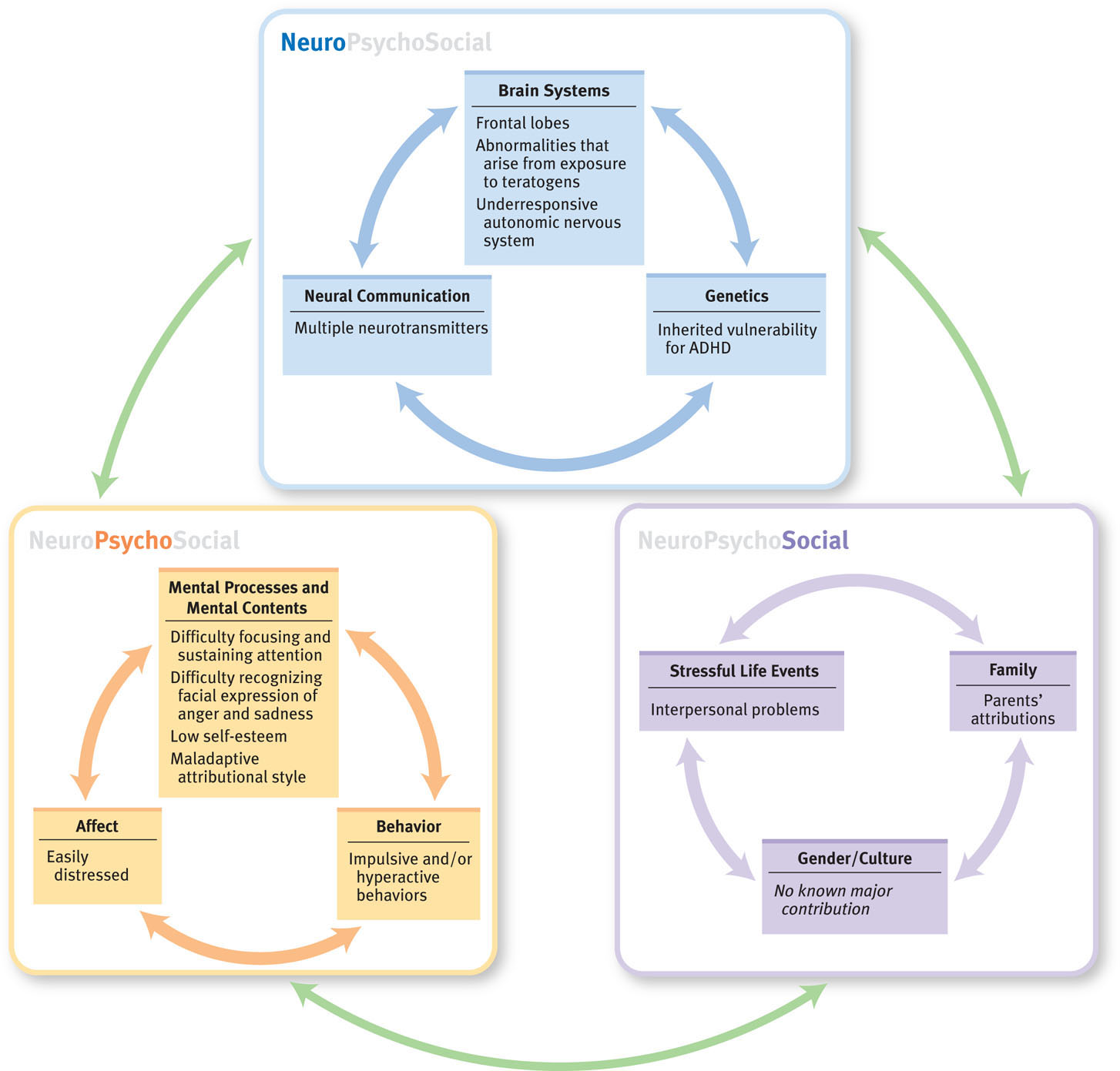

Feedback Loops in Understanding Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder

In this section, we examine how the different factors related to ADHD create feedback loops (see Figure 14.1). Current research suggests that psychological and social factors contribute to the development of ADHD in people whose genes lead them to be neurologically vulnerable to the disorder.

Consider the finding that children with ADHD are less accurate at recognizing sad and angry facial expressions (Pelc et al., 2006). Such deficits, particularly difficulty in recognizing anger, are associated with more interpersonal problems. These results suggest that when peers or adults (typically parents or teachers) show—rather than tell—their displeasure to a child who has ADHD, that child is less likely to perceive (psychological factor) the social cue (social factor) than is a child who does not have the disorder. This difficulty in perceiving others’ displeasure in turn creates additional tension for both the child and those who interact with him or her. In fact, children with ADHD are more likely than those without the disorder to be rejected by their peers (Mrug et al., 2009). Moreover, other people’s responses to the child’s behavior (social factor) in turn influence how the child comes to feel about himself or herself (psychological factor; Brook & Boaz, 2005).

Other research results suggest that the family environment is associated with ADHD. In particular, family conflict is higher in families that include a child with ADHD than in control families (Pressman et al., 2006). However, do family environments that are higher in conflict play a role in causing a child to develop ADHD? Or do the symptoms of the disorder—inattention, hyperactivity, or impulsivity—create more tension in the family? Or do difficulties associated with the disorder, such as difficulty in recognizing angry or sad facial expressions, increase family tension? It may be that all these possible influences occur.

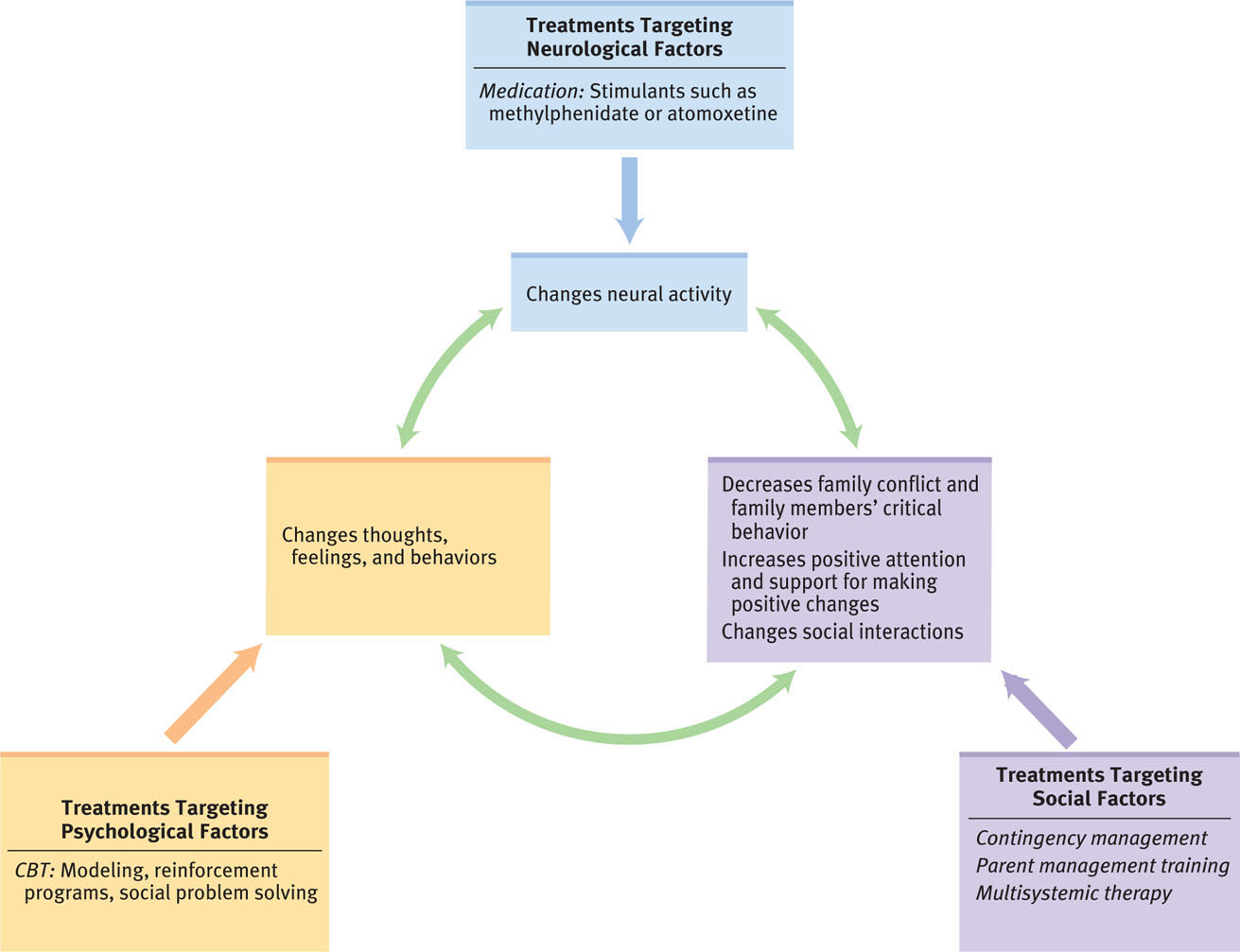

Treating Disorders of Disruptive Behavior and Attention: Focus on ADHD

Treatments for disorders of disruptive behavior and attention are usually comprehensive, targeting more than one type of factor and sometimes all three types of factors. And children with ADHD may be legally entitled to special services and accommodations in school. Specific treatments for ADHD focus both on attentional symptoms and, when present, on hyperactivity/impulsivity symptoms.

Targeting Neurological Factors: Medication

Medication for ADHD often treats symptoms of both ADHD and also comorbid oppositional defiant disorder or conduct disorder. One type of medication for ADHD targets dopamine, which plays a key role in the functioning of the frontal lobes (Solanto, 2002). Many of these medications are stimulants, which may sound counterintuitive because people with ADHD don’t seem to need more stimulation. However, these stimulants increase attention and reduce general activity level and impulsive behavior. Although the mechanism that produces these effects is not entirely understood, the medications appear to have their effects by disrupting the reuptake of dopamine, leaving more dopamine in the synapse and thus correcting at least some of the imbalance in this neurotransmitter that has been observed in the brains of people with ADHD (Volkow et al., 2005). In addition, this disorder may arise in part because the person is understimulated and hence seeks additional stimulation; by providing stimulation internally, the medications reduce the need to seek it externally.

471

Stimulant medications for ADHD may contain methylphenidate (such as Ritalin, Concerta, and Focalin) or an amphetamine (such as Adderall) and are available in relatively short-acting formulas (requiring two or three daily doses) and in a timed-release formula (requiring only one dose per day). Methylphenidate is also available as a daily skin patch. About 65–75% of people with ADHD who receive stimulants improve (compared to 4–30% of controls who receive placebos), and the side effects are not severe for most people (Pliszka, 2007; Pliszka et al., 2006). In fact, stimulants have been shown to improve the functioning of various brain areas that are impaired in this disorder (Bush et al., 2008; Clarke et al., 2007; Epstein et al., 2007).

472

Another medication for ADHD is atomoxetine (Strattera); it is a noradrenaline reuptake inhibitor, not a stimulant. Atomoxetine has effects and side effects similar to those of the stimulant medications (Kratochvil et al., 2002) and currently is the medication of choice for people with both ADHD and substance abuse.

Medications for ADHD reduce impulsive behaviors, which seems to decrease related aggressive behaviors (Frick & Morris, 2004). This effect can have wide-ranging consequences. As noted earlier, the symptoms of ADHD can give rise to feedback loops with a child’s family or with peers, and these feedback loops can cause disruptive behaviors to escalate. Successful treatment with medication disrupts these feedback loops, reducing the frequency and intensity of disruptive behaviors, which in turn leads family members and peers not to become as irritated and angry, which thereby reduces their undercutting the child’s self-esteem (Frick & Muñoz, 2006; Hinshaw et al., 1993; Jensen et al., 2001).

Targeting Psychological Factors: Treating Disruptive Behavior

Treatments that target psychological factors have been developed for all three disruptive disorders. These treatments usually employ behavioral and cognitive methods to address disruptive behaviors. One reason for such behaviors is that children with any of these disorders tend to have low frustration tolerance and difficulty in working for delayed—rather than immediate—reward. Thus, behavioral methods may focus on helping such children restrain their behavior and accept a delayed reward. Specific techniques include a reinforcement program that uses concrete rewards, such as a toy, and social rewards, such as praise or special time with a parent. These methods slowly increase the delay until the child receives either a concrete reward (“Now you can have that toy”) or a social reward (“You did a great job, I’m proud of you”), which should motivate the child to control behavior for a delayed reward in the future (Sonuga-Barke, 2006).

Behavioral methods for treating all three disorders may also be used to modify social behaviors, such as not responding to others aggressively or not interrupting others. For example, when children enter preschool or kindergarten, this may be the first time they have to sit quietly for a length of time and wait for a turn to participate. Often the teacher will ask children to raise a hand and wait until called on to answer a question. A child with ADHD will be more likely than other children to speak out of turn or to keep vigorously waving a raised hand, trying to get the teacher’s attention. A program of rewarding the child for increasingly longer times of not speaking out or waving frantically can teach the child to behave with more restraint, which can ease relations with classmates.

Cognitive methods seek to enhance children’s social problem-solving abilities. Specifically, the therapist helps the child interpret social cues in a more realistic way—for instance, acknowledging that the other person may not have hostile motives when he asked you to move your backpack—and develop more appropriate social goals and responses (Dodge & Pettit, 2003). Through skills-building, modeling, and role-playing, the treatment also helps the child to learn how to inhibit angry or impulsive reactions and to learn more effective ways to respond to others. The therapist praises the child’s successes in these areas. To enhance the generalizability of the new skills to life outside the therapy session, parents and teachers may be asked to help with role-playing and modeling and to use praise in their contacts with the child. CBT for adults with ADHD (which focuses on helping the person with planning, organization, and coping with distractions) is also effective (Safren et al., 2010).

473

Targeting Social Factors: Reinforcement in Relationships

Most of the treatments that target social factors are designed to help parents—and teachers, when necessary—to use operant conditioning principles to shape a child’s prosocial behavior and decrease defiant or impulsive behavior.

Contingency Management: Changing Parents’ Behavior

Contingency management A procedure for modifying behavior by changing the conditions that led to, or are produced by, it.

Contingency management is a procedure for modifying behavior by changing the conditions that lead to, or are produced by, the behavior. Treatment may target parents of children with ADHD to help them set up a contingency management program with their child—particularly in cases in which the parents have been inconsistent in their use of praise (and other reinforcers) or punishment (Frick & Muñoz, 2006).

The first step of contingency management training with parents is psychoeducation—teaching the parents that the symptoms are not the result of intentional misbehavior but part of a disorder (Barkley, 1997, 2000). The subsequent training then is intended to:

- change parents’ beliefs about the reasons for their child’s behavior so that parents approach their child differently and develop realistic goals for their child’s behavior;

- help parents to institute behavior modification, which includes paying attention to desired behaviors, being consistent and clear about directions, and developing reward programs; and

- teach parents to respond consistently to misbehavior.

Parent training targets social factors—interactions between parents and child. Changes in the way parents think about and interact with their child, in turn, change the child’s ability to control behavior (psychological factor). Parent training may be the best treatment for families who have children with mild ADHD or preschoolers with ADHD (Kratochvil et al., 2004).

Parent Management Training

Parent management training is designed to combine contingency management techniques with additional techniques that focus on improving parent–child interactions generally—improving communication and facilitating real warmth and positive interest in the parent for his or her child (Kazdin, 1995).

Multisystemic Therapy

Multisystemic therapy (Henggeler et al., 1998) is based on family systems therapy and focuses on the context in which the child’s behavior occurs: with peers, in school, in the neighborhood, and in the family. This comprehensive treatment may involve family and couples therapy, interventions with peers, CBT with the child, and an intervention in the school (such as meeting with the child’s teacher or directly assisting in the classroom to help the child manage his or her behavior). The specific techniques employed are tailored to change systems in the child’s life in order to manage his or her behavior better.

Feedback Loops in Treating Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder

At first glance, medication might seem to have its effects solely through neurological mechanisms, but this isn’t so. Taking medication (neurological factor) not only leads to increased control of attention and hyperactive or impulsive behaviors, but it is also associated with higher levels of self-esteem (psychological factor; Frankel et al., 1999), which can lead a child not to seek attention as vigorously. Moreover, such increased control of attention and behavior also improves social functioning (social factor; Chacko et al., 2005). And better social functioning feeds back to improve self-esteem.

Other feedback loops originate from programs for parents or the family (which target social factors); such interventions in turn create feedback loops with psychological factors—improving the child’s thoughts, feelings, and behaviors. Figure 14.2 illustrates feedback loops among the various factors that are used to treat ADHD.

474

Thinking Like A Clinician

Nikhil has some first-hand familiarity with oppositional defiant disorder and conduct disorder: He went to a large middle school and large high school, where some kids always acted up and got into trouble. And during high school and college, some of his friends and then one of his roommates had ADHD. Even though Nikhil may think he knows something about disruptive behavior disorders and ADHD, based on what you have read, what information about these disorders should he be given before he begins to teach, and why?