15.1 Normal Versus Abnormal Aging and Cognitive Functioning

The neuropsychologist assessing Mrs. B. needed to determine whether her disturbances in memory, mood, and behavior were normal for an 87-year-old, particularly one with a variety of medical problems. And, if her memory, mood, and behavior weren’t in the normal range, given her circumstances, what, specifically, were her difficulties? And what could account for them? The neuropsychologist initially assessed Mrs. B. using a clinical interview (discussed in Chapter 3), observing her as well as noting her responses to questions:

Mrs. B. arrived promptly for her appointment, accompanied by her private-duty nurse. She was well-groomed and alert but ambulated slowly, leaning against the railing on the wall to maintain her balance; she was also unsteady on rising and standing from a chair. She was fluent and willing to talk at great length about her situation, although her speech was often repetitive and tangential. Mood was…positive during the interview. She denied hallucinations, delusions, or suicidal ideation but admitted to some depression, which she felt had improved somewhat on antidepressant medication. She was able to describe some aspects of her experience at the [nursing home] and gave several examples of the types of things that annoyed her at the current board-and-care home.

(La Rue & Watson, 1998, p. 6)

Mrs. B. was able to remember aspects of her nursing home experience that she didn’t like, but she forgot other types of information, such as her upcoming plans. In the normal course of events, however, various cognitive functions tend to decline with advancing age. Even healthy older adults have some cognitive deficits, compared to their younger selves, and these must be taken into account when attempting to determine whether an older person has a disorder. Thus, the neuropsychologist must assess whether Mrs. B.’s functioning has declined and, if so, whether this decline is beyond what occurs with the normal aging process. In this section, we examine what happens to cognitive functioning during normal aging and then examine the neurological factors that can disrupt cognitive functioning.

479

Cognitive Functioning in Normal Aging

Most—although not all—aspects of cognitive functioning remain relatively stable during older adulthood.

Intelligence

GETTING THE PICTURE

© URF/AGE Fotostock

Crystallized intelligence A type of intelligence that relies on using knowledge to reason in familiar ways; such knowledge has “crystallized” from previous experience.

Let’s first examine intelligence, which can be divided into two types (Cattell, 1971): Crystallized intelligence relies on using knowledge to reason in familiar ways; such knowledge has “crystallized” from previous experience. For example, an avid fisherman can use knowledge gleaned from prior experience to reason about where fish are likely to be lurking in a stream. Normally, crystallized intelligence remains stable or actually increases with age, even among older adults; crystallized intelligence is often assessed by tests that measure verbal ability, and these tests often allow ample time for people to respond to questions. In contrast, fluid intelligence relies on the ability to create novel strategies to solve new problems, without relying solely on familiar approaches. For example, fluid intelligence would be required to devise a new way to catch fish without a hook, line, and sinker—perhaps using a shirt or basket as a net. Fluid intelligence relies on executive functions, which include the abilities to think abstractly, to plan, and to exert good judgment. Fluid intelligence is typically assessed with tests of visual-motor skills, problem solving, and perceptual speed (Salthouse, 2005). As adults age, their scores on most measures of fluid intelligence decline.

Fluid intelligence A type of intelligence that relies on the ability to create novel strategies to solve new problems, without relying solely on familiar approaches.

480

Normal cognitive decline must be judged in relation to each person’s own baseline. An older adult who starts out with a high IQ and has functioned well will probably be able to continue to function well even with the normal decline of aging. In contrast, the functioning of someone who has a lower IQ initially (such as in the low normal range, an IQ between 85 and 100) will be affected more dramatically—perhaps to the point where his or her ability to function independently is curtailed (Harvey, 2005a).

Memory

Memory is not a single ability, and various aspects of it are affected in different ways by aging.

The elderly (generally considered to be people aged 65 and older; World Health Organization [WHO], 2009) tend to have problems recalling previously stored information. To recall information is to become aware of that information after voluntarily attempting to “look it up” in memory. In contrast, healthy older people often have little difficulty with recognition; to recognize information requires first perceiving it and then comparing it to information previously stored in memory to determine whether the perceived information matches the stored information.

For example, older people sometimes have trouble recalling the names of common objects on demand. Thus, they might say, “I went to the store to buy a ‘thingamajig’ this morning.” Despite difficulty recalling the names of objects, cognitively healthy older people can describe the object or recognize the correct word when someone else says it, and may even recall the correct word a few minutes later when talking about something else (Nicholas et al., 1985).

However, in spite of these difficulties, healthy older people can often recall temporarily forgotten names of common things when given cues or hints. Moreover, with normal aging, the ability to recall personal information is preserved; people can recall important episodes from their past.

Processing Speed, Attention, and Working Memory

People generally process information more slowly as they reach old age. One explanation for this slowed processing speed is that the myelin sheaths coating the axons of neurons degrade or disappear, which then causes the neurons’ signals to dissipate—and hence communication among brain areas is impaired (Andrews-Hanna et al., 2007).

The slowed processing speed that occurs with advanced age affects many cognitive functions. For example, consider storing new information in memory: Older adults generally acquire new information at a slower rate and thus typically need more exposure to the to-be-stored material; they also need more practice in retrieving the information after they have stored it. For these reasons, elderly people may be impaired when carrying out tasks that require rapidly recalling and using stored information (Fillit et al., 2002; Salthouse, 2001).

Another cognitive function that often declines with age is attention. Attention involves selecting some information for more careful analysis: what a person pays attention to gets processed more fully than what he or she does not pay attention to. In part because processing slows down with aging, the ability to switch attention sequentially among multiple tasks (known as multitasking) is likely to decline as people age (Parasuraman et al., 1989). Thus, older adults may have a harder time performing tasks such as scanning e-mail while talking on the phone.

481

Elderly people typically have problems using working memory (De Beni & Palladino, 2004; Li, Lindenberger, & Sikström, 2001). Working memory requires keeping information activated (so that you are aware of it) while operating on it in a specific way; for example, holding the steps of a recipe in mind while cooking and progressing from one step to the next requires working memory. Working memory relies on executive functions that are implemented in the frontal lobes, which don’t operate as effectively in elderly people as they do in younger people.

Psychological Disorders and Cognition

Most older adults don’t have a psychological disorder; in fact, older adults have the lowest prevalence of psychological disorders and of significant psychological distress of any age group (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2012; Karlin et al., 2008). But when an older person does have a psychological disorder, its symptoms can impair cognitive functioning. Thus, before assuming that an older person’s deteriorated cognitive functioning is a result of a neurocognitive disorder, the clinician must first determine whether the deterioration could result from another sort of psychological disorder. For instance, Mrs. B. had a history of depression and described herself as having a “hot temper” even as a young adult. Mrs. B.’s daughter described her mother “as always somewhat self-centered and suspicious of the motives of others, but this had worsened noticeably in recent years, to the point where she had been isolated within her own home,” which led to the move to the nursing home (La Rue & Watson, 1998, p. 6).

The neuropsychologist must determine whether Mrs. B.’s memory problems might reflect a psychological disorder—such as depression, an anxiety disorder, or schizophrenia.

Depression

Older adults are less likely than their younger counterparts to be diagnosed with depression. When they are depressed, however, the symptoms often differ from those of younger adults: Older depressed adults have more anxiety, agitation, and memory problems (Segal, 2003). Thus, cognitive functioning is affected by depression both directly (memory problems) and indirectly (anxiety and agitation affect attention, concentration, and other mental processes; see TABLE 15.1).

| Information Processing Speed |

|

| Attention and Concentration |

|

| Executive Function |

|

| Memory |

|

| Source: Potter & Steffens, 2007. For more information see the Permissions section. |

In addition, a mental health clinician must determine whether symptoms of depression in an older person could be caused by a neurocognitive disorder: Some symptoms of depression, such as fatigue, may be caused by brain changes associated with a neurocognitive disorder (Puente, 2003). Mrs. B. had a history of depression and was taking antidepressant medication. However, the neuropsychologist who assessed Mrs. B.’s cognitive functioning determined that the difficulties she was having were not a result of depression (La Rue & Watson, 1998). Mr. Rosen, in Case 15.1, had cognitive problems that may or may not have been related to his depression.

482

CASE 15.1 • FROM THE OUTSIDE: Normal Aging or Something More?

Maurice Rosen was 69 when he made an appointment for a neurological evaluation. He had recently noticed that his memory was slipping and he had problems with concentration that were beginning to interfere with his work as a self-employed tax accountant. He complained of slowness and losing his train of thought. Recent changes in the tax laws were hard for him to learn, and his wife said he was becoming more withdrawn and reluctant to initiate activities. However, he was still able to take care of his personal finances and accompany his wife on visits to friends. Although mildly depressed about his disabilities, he denied other symptoms of depression, such as disturbed sleep or appetite, feelings of guilt, or suicidal ideation.

Mr. Rosen has a long history of treatment for episodes of depression, beginning in his 20s. He has taken a number of different antidepressants and once had a course of electroconvulsive therapy. As recently as 6 months before this evaluation, he had been taking an antidepressant.

(Spitzer et al., 2002, p. 70)

Anxiety Disorders

Like depression, anxiety disorders are less common among older adults than among younger adults. The anxiety disorder most prevalent among older adults is generalized anxiety disorder (Segal, 2003). About 5% of older adults have generalized anxiety disorder, most often along with depression; in about half the cases, the anxiety disorder only emerged when the person became older (Flint, 2005). The fears and worries that accompany generalized anxiety disorder can impair cognitive functioning, in part because the person may become preoccupied with fears and worries and have difficulty paying attention and concentrating.

Schizophrenia

About 15% of people with schizophrenia are older than 44 when they have their first psychotic episode (Cohen et al., 2000). Schizophrenia can involve both positive symptoms, such as delusions and hallucinations, and negative symptoms, such as an absence of initiative (avolition; see Chapter 12); these symptoms can also occur with neurocognitive disorders.

Medical Factors That Can Affect Cognition

In some cases, impaired cognitive functioning is not a result of a neurocognitive disorder but rather is caused by medical problems. We summarize some of these problems in the following sections.

Diseases and Illnesses

Various physical diseases and illnesses can affect cognition—directly or indirectly. Some medical illnesses, such as encephalitis (a viral infection of the brain) and brain tumors, directly affect the brain and, in doing so, affect cognition. The specific cognitive deficits that arise depend on the particular features of the illness, such as the size and location of a brain tumor.

Some chronic diseases or illnesses indirectly affect cognition by creating pain, which can disrupt attention, concentration, and other mental processes. For example, arthritis can cause chronic pain, and the aftermath of surgery can cause acute pain. In addition, pain can interfere with sleep, which further impairs mental processes. These detrimental effects may be temporary, so that cognitive functioning improves as the symptoms resolve or the pain recedes. In other cases, however, the person may never return to his or her prior level of functioning.

483

In still other cases, an older adult may appear to have impaired cognitive functioning but actually has undiagnosed or uncorrected sensory problems, such as hearing loss or vision problems. If someone chronically mishears what is said, he or she will seem “not with it” or “senile” when, in fact, the problem is simply that the person thinks the topic of conversation is something other than what it actually is.

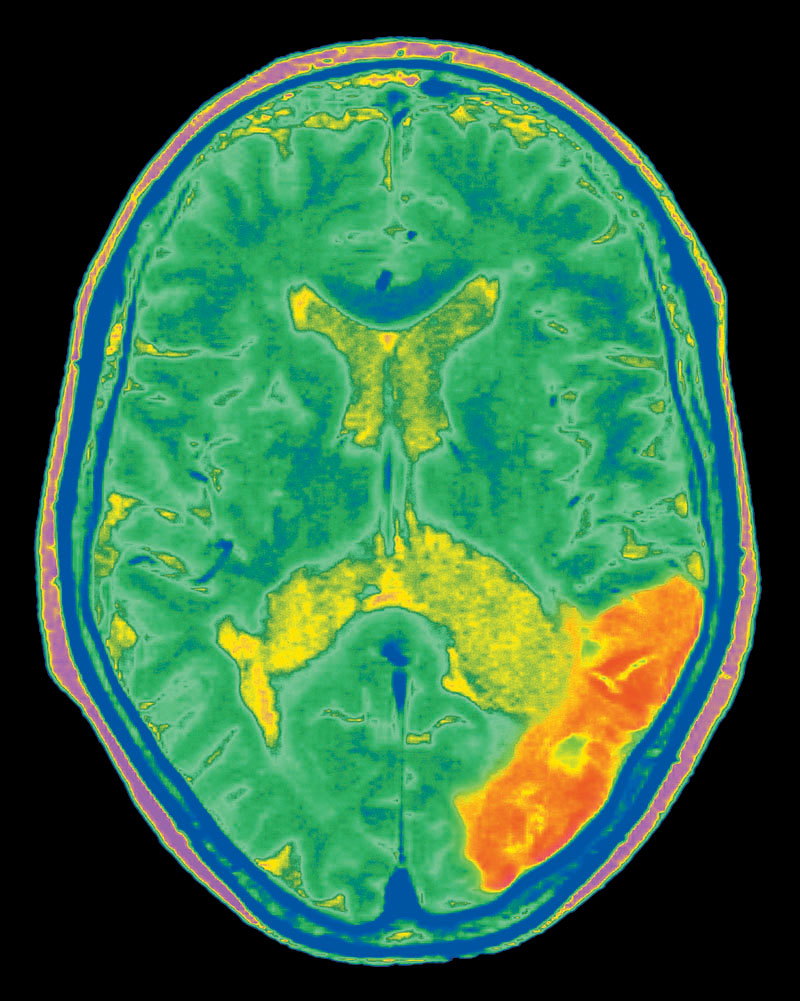

Stroke

Stroke The interruption of normal blood flow to or within the brain, which results in neuronal death.

A stroke (so named because it was originally assumed to be a “stroke of God”) is the interruption of normal blood flow to or within the brain (often because of an obstruction—such as a blood clot—in a blood vessel). The result is that part of the brain fails to receive oxygen and nutrients, and the neurons in that area die. The cognitive, emotional, and behavioral consequences of a stroke depend crucially on which specific group of neurons is affected; depending on their location in the brain, different deficits are produced. The most common deficits are discussed below.

Aphasia

Aphasia A neurological condition characterized by problems in producing or comprehending language.

Aphasia is a problem in using language. (The word aphasia literally means “an absence of speech.”) Traditionally, there are two main types of aphasia, each named after the neurologist who first characterized it in detail. Broca’s aphasia is characterized by problems producing speech. Patients with Broca’s aphasia speak haltingly, and their speech can be very telegraphic—consisting of only the main words. In contrast, Wernicke’s aphasia is characterized by problems with both comprehending language and producing meaningful utterances. Although these patients may appear to speak fluently, they often order words incorrectly and sometimes make up nonsense words.

Broca’s aphasia A neurological condition characterized by problems producing speech.

Wernicke’s aphasia A neurological condition characterized by problems comprehending language and producing meaningful utterances.

Agnosia

Patients who have agnosia have difficulty understanding what they perceive, although neither their sensory abilities nor their knowledge about objects is impaired. Many forms of agnosia can arise. For example, prosopagnosia is a particular type of agnosia in which the person cannot recognize faces—often including his or her own face in a mirror! Some forms of agnosia can lead to disorientation, which must be distinguished from disorientation that occurs with dementia (to be discussed shortly).

Apraxia

Apraxia A neurological condition characterized by problems in organizing and carrying out voluntary movements even though the muscles themselves are not impaired.

Another medical condition that can affect cognitive functioning is apraxia (Kosslyn & Koenig, 1995), which involves problems in organizing and carrying out voluntary movements even though the muscles themselves are not impaired. The problem is in the brain, not in the muscles. Apraxia can take a variety of forms. For example, some patients have trouble sequencing movements (such as the movements necessary to light a candle, that is, taking out a match, striking it, and holding the flame to the wick). Clinicians must distinguish between such problems with voluntary movements and the avolition (difficulty initiating or following through with activities) that may accompany schizophrenia (noted in Chapter 12).

484

Head Injury

Cognitive disorders may arise from head injuries—which may result from a car accident, from a fall, or in a variety of other ways. The specific cognitive deficits that develop depend on the exact nature of the head injury. The same kinds of deficits that follow a stroke can also occur after a head injury.

Substance-Induced Changes in Cognition

We saw in Chapter 9 that some people take substances (including prescribed medications) to alter their level of awareness or their emotional or cognitive state. But medications or exposure to toxic substances can produce unintended changes in attention, memory, judgment, or other cognitive functions, particularly when a person takes a high dose. In fact, older people are more sensitive than others to the effects of medications, and so a dose appropriate for a younger adult is more likely to have negative effects or side effects in an older adult (Mort & Aparasu, 2002). Even anesthesia for surgery can subsequently affect cognitive functioning (Thompson, 2003).

Thinking Like A Clinician

Evan is a first-year college student who lives with his grandmother because her home is near his school. Before he started living with her, he had spent only a few days at a time with her, usually on trips with his mother. Now that he’s spending more time with his grandmother, he has noticed that she frequently tells him the same stories from her childhood. When she asks him to do an errand, she sometimes forgets the words of the objects she wants him to bring home or the shop she wants him to visit. And sometimes when he enters a room that she’s in, she seems momentarily confused about who he is and why he’s there. Evan is concerned that there is something “not right” with his grandmother, and is wondering whether he should suggest that she be evaluated by a doctor. Based on what you’ve learned about normal versus abnormal changes with aging, what specific advice would you give to Evan to help him determine whether his grandmother’s cognitive problems are likely to be those of normal aging (and so Evan need not urgently suggest that she see her doctor)?