16.3 Dangerousness: Legal Consequences

Andrew Goldstein’s attack on Kendra Webdale wasn’t the first time he had engaged in dangerous behavior, and his dangerous behavior wasn’t a secret:

In the two years before Kendra Webdale was instantly killed on the tracks, Andrew Goldstein attacked at least 13 other people. The hospital staff members who kept treating and discharging Goldstein knew that he repeatedly attacked strangers in public places.

He was hospitalized after assaulting a psychiatrist at a Queens clinic. [The clinic note from November 14, 1997, reads]: “Suddenly, without any warning, patient springs up and attacks one of [the] doctors, pushing her into a door and then onto the floor. He was hospitalized after threatening a woman, [again] after attacking two strangers at a Burger King [and yet again] after fighting with an apartment mate.” [A note from March 2, 1998, says]: “Broke down roommate’s door because he could not control the impulse.” And particularly chilling, six months before Kendra Webdale’s death, he was hospitalized for striking another woman he did not know on a New York subway.

(Winerip, 1999a)

Goldstein’s history indicates that he had become dangerous. Dangerousness, a legal term, refers to someone’s potential to harm self or others. Determining whether someone is dangerous, in this sense, rests on assessing threats of violence to self or to others, or establishing an inability to care for oneself. Dangerousness can be broken down into four components regarding the potential harm (Brooks, 1974; Perlin, 2000c):

- severity (how much harm might the person inflict?),

- imminence (how soon might the potential harm occur?),

- frequency (how often is the person likely to be dangerous?), and

- probability (how likely is the person to be dangerous?)

Dangerousness The legal term that refers to someone’s potential to harm self or others.

516

Evaluating Dangerousness

Clinicians are sometimes asked to evaluate how dangerous a patient may be—specifically, the severity, imminence, and likelihood of potential harm (McSherry & Keyzer, 2011; Meyer & Weaver, 2006). Such evaluations are either/or in nature—the individual is either deemed not to be dangerous (or at least not dangerous enough to violate confidentiality) or deemed to be dangerous, in which case, confidentiality is broken or the patient remains in a psychiatric facility in order to protect the individual from self-harm or to protect others (Otto, 2000; Quattrocchi & Schopp, 2005). Prior to each discharge from a hospital or psychiatric unit, Goldstein had to be evaluated for dangerousness; he was then discharged because he was deemed not dangerous, or not dangerous enough.

Researchers set out to determine the risk factors that could best identify which patients discharged from psychiatric facilities would subsequently act violently. A summary of the findings appears in TABLE 16.3.

| Patient’s Prior Arrests |

|

| Patient Experienced Child Abuse |

|

| Patient’s Father… |

|

| Patient’s Demographics |

|

| Patient’s Diagnosis |

|

| Other Clinical Information About Patient |

|

| Source: Monahan et al., 2001. For more information see the Permissions section. |

Confining people who are deemed to be dangerous involves taking away their liberty—their freedom—and is not done lightly. Loitering or yelling at “voices” should not be considered legally dangerous. Rather, the legal system allows a person to be incarcerated or hospitalized, or to continue to be incarcerated or hospitalized, in only two types of situations:

- when the person has not yet committed a violent crime but is perceived to be at imminent risk to do so, or

- when the person has already served a prison term or received mandated treatment in a psychiatric hospital and is about to be released but is perceived to be at imminent risk of behaving violently.

To prevent such people from harming themselves or others, the law provides that they can be confined as long as they continue to pose a significant danger.

Actual Dangerousness

Although we have focused on the relationship between some forms of mental illness and violence, as occurred with Goldstein, most mentally ill people are not violent. Mentally ill people who engage in criminal acts receive a lot of media attention, which may give the impression that the mentally ill commit more crimes than they really do (Pescosolido et al., 1999). In fact, criminal behavior among the mentally ill population is no more common than it is in the general population (Fazel & Grann, 2006). Indeed, when mentally ill people are in jail or prison, it is usually for minor nonviolent offenses related either to trying to survive (e.g., stealing food) or to substance abuse—the mental illness usually is not a direct cause of the incarceration (Hiday & Wales, 2003).

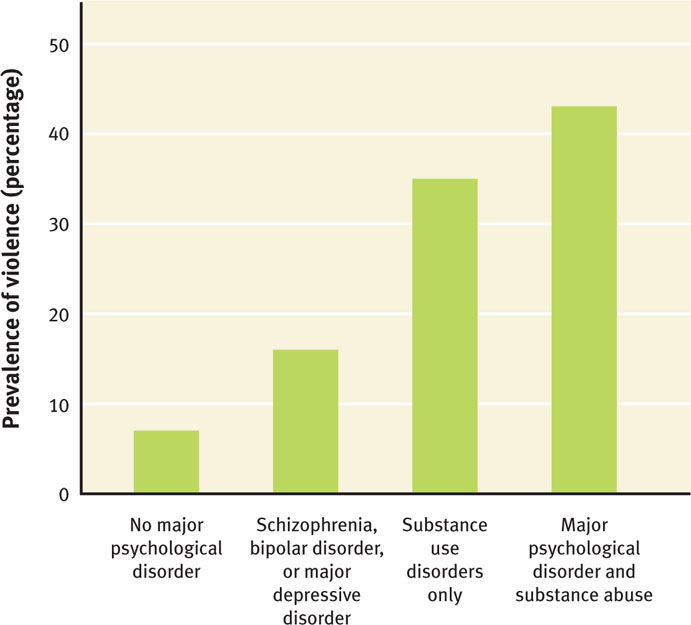

However, two sets of circumstances related to mental illness do increase dangerousness: (1) when the mental illness involves psychosis, and the person may be a danger to self as well as others (Fazel & Grann, 2006; Wallace et al., 2004)—particularly when delusions lead the mentally ill person to be angry (Coid et al., 2013), and especially (2) when serious mental illness is combined with substance abuse (Howsepian, 2011; Maden et al., 2004). The relationship between various major mental illnesses, substance use disorders, and violence is shown in Figure 16.1.

Confidentiality and the Dangerous Patient: Duty to Warn and Duty to Protect

In the 1960s, University of California college student Prosenjit Poddar liked fellow student Tatiana Tarasoff. However, his interest in her was greater than was hers in him. He became depressed by her rejection and began treatment with a psychologist. During the course of his treatment, his therapist became concerned that Mr. Poddar might hurt or kill Ms. Tarasoff. (Poddar had purchased a gun for that purpose.) The therapist informed campus police that Poddar might harm Tarasoff. The police briefly restrained him, but they determined that he was rational and not a threat to Tarasoff. Ms. Tarasoff was out of the country at the time, and neither she nor her parents were alerted to the potential danger. Two months later, Poddar killed Tarasoff.

517

Tarasoff rule A ruling by the Supreme Court of California (and later other courts) that psychologists have a duty to protect potential victims who are in imminent danger.

Her parents sued the psychologist, saying that Tarasoff should have been protected either by warning her or by having Poddar committed to a psychiatric facility. In what has become known as the Tarasoff rule, the Supreme Court of California (and later courts in other states) ruled that psychologists have a duty to protect potential victims who are in imminent danger (Tarasoff v. Regents of the University of California, 1974, 1976). This rule has been extended to other mental health clinicians.

Mental health professionals who decide that a patient is about to harm a specific person can choose to do any of the following (Quattrocchi & Schopp, 2005):

- warn the intended victim or someone else who can warn the victim,

- notify law enforcement agencies, or

- take other reasonable steps to prevent harm (depending on the situation), such as having the patient voluntarily or involuntarily committed to a psychiatric facility for an extended evaluation (that is, have the patient confined).

The Tarasoff rule effectively extended a clinician’s duty to warn of imminent harm to a duty to protect (Werth et al., 2009). The clinician must violate confidentiality in order to take reasonable care to protect an identifiable—or reasonably foreseeable—victim (Brady v. Hopper, 1983; Cairl v. State, 1982; Egley, 1991; Emerich v. Philadelphia Center for Human Development, 1998; Schopp, 1991; Thompson v. County of Alameda, 1980). Note, however, that potential danger to property is not sufficient to compel clinicians to violate confidentiality (Meyer & Weaver, 2006).

518

Maintaining Safety: Confining the Dangerously Mentally Ill Patient

A dangerously mentally ill person can be confined via criminal commitment or civil commitment.

Criminal Commitment

Criminal commitment is the involuntary commitment to a mental health facility of a person charged with a crime. This can happen before trial or after trial:

- If the defendant hasn’t yet had a trial, the time at the mental health facility is used to

- evaluate whether he or she is competent to proceed with the legal process (for instance, is the defendant competent to stand trial?) and

- provide treatment so that the defendant can become competent to participate in the legal proceedings.

- If the defendant has had a trial and was acquitted due to insanity (Meyer & Weaver, 2006).

Criminal commitment The involuntary commitment to a mental health facility of a person charged with a crime.

Based on a 1972 ruling (Jackson v. Indiana, 1972), it is illegal to confine someone indefinitely under a criminal commitment. Thus, a defendant found not competent to stand trial cannot remain in a mental health facility for life. But the law is unclear as to exactly how long is long enough. Judges have discretion about how long they can commit a defendant to a mental health facility to determine whether treatment may lead to competence to stand trial. Such treatment may last several years. If the defendant does not become competent, he or she may not remain committed for the original reason—to receive treatment in order to become competent. In this case, the process of deciding whether he or she should be released from the mental health facility proceeds just as it does for anyone who hasn’t been criminally charged. If the individual is deemed to be dangerous, however, he or she may be civilly committed.

Civil Commitment

Civil commitment The involuntary commitment to a mental health facility of a person deemed to be at significant risk of harming himself or herself or a specific other person.

When an individual hasn’t committed a crime but is deemed to be at significant risk of harming himself or herself, or of harming a specific other person, the judicial system can confine that individual in a mental health facility, which is referred to as a civil commitment. This is the more common type of commitment.

There are two types of civil commitment: (1) inpatient commitment to a 24-hour inpatient facility, and (2) outpatient commitment to some type of monitoring and/or treatment program (Meyer & Weaver, 2006). Civil commitment grows out of the idea that the government can act as a caregiver, functioning as a “parent” to people who are not able to care for themselves; this legal concept is called parens patriae.

Civil commitments can conflict with individual rights, so guidelines have been created to protect patients’ rights by establishing the circumstances necessary for an involuntary commitment, the duration of such a commitment—and who decides when it ends—as well as the right to refuse a specific type of treatment or treatment in general (Meyer & Weaver, 2006). It may seem that civil commitments are always forced or coerced, but that is not so. Some civil commitments are voluntary (that is, the patient agrees to the hospitalization); however, some “voluntary” hospitalizations may occur only after substantial coercion (Meyer & Weaver, 2006).

Many people who are civilly committed belong to a subset of the mentally ill population—those who are overrepresented in the revolving door after their release that leads to jails or hospitals. This revolving door evolved because lawmakers and clinicians wanted a more humane approach to dealing with the mentally ill, by treating them in the least restrictive setting—before their condition deteriorates to the point where they harm themselves or others (Hiday, 2003).

519

Mandated Outpatient Commitment

Mandated outpatient commitment developed in the 1960s and 1970s, along with increasing deinstitutionalization of patients from mental hospitals; the goal was to develop less restrictive alternatives to inpatient care (Hiday, 2003). Such outpatient commitment may consist of legally mandated treatment that includes some type of psychotherapy, medication, or periodic monitoring of the patient by a mental health clinician. The hope is that mandated outpatient commitment will preempt the “revolving door” cycle that occurs for many patients who have been committed: (1) getting discharged from inpatient care, (2) stopping their medication, (3) becoming dangerous, and (4) ending up back in the hospital through a criminal or civil commitment or landing in jail.

Researchers have investigated whether mandated outpatient commitment is effective: Are the patient and the public safer than if the patient was allowed to obtain voluntary treatment after discharge from inpatient care? Does mandated outpatient treatment result in less frequent hospitalizations or incarcerations for the patient? To address these questions, one study compared involuntarily hospitalized patients who either were invited to use psychosocial treatment and services voluntarily upon discharge or who were court-ordered to obtain outpatient treatment for 6 months—and made frequent use of services (between 3 and 10 visits/month) (Hiday, 2003; Swartz et al., 2001). The results indicated that those who received mandated outpatient treatment:

- went back into the hospital less frequently and for shorter periods of time,

- were less violent,

- were less likely to be victims of crime themselves, and

- were more likely to take their medication or obtain other treatment, even after the mandated treatment period ended.

Other studies have found similar benefits of mandated outpatient commitment (Hough & O’Brien, 2005). That said, it is also clear that mandated outpatient commitment is not effective without adequate funding for increased therapeutic services (Perlin, 2003; Rand Corporation, 2001). In what follows we examine what happens without adequate funding.

The Reality of Treatment for the Chronically Mentally Ill

Andrew Goldstein generally wanted to be hospitalized and repeatedly tried to make that happen:

He signed himself in voluntarily for all 13 of his hospitalizations. His problem was what happened after discharge. The social workers assigned to plan his release knew he shouldn’t have been living on his own, and so did Goldstein, but everywhere they looked they were turned down. They found waiting lists for long-term care at state hospitals, waiting lists for supervised housing at state-financed group homes, waiting lists for a state-financed intensive-case manager, who would have visited Goldstein daily at his apartment to make sure he was coping and taking his meds.

More than once he requested long-term hospitalization at Creedmoor, the state hospital nearby. In 1997, he walked into the Creedmoor lobby, asking to be admitted. “I want to be hospitalized,” he said. “I need a placement.” But in a cost-cutting drive, New York [had] been pushing hard to reduce its patient census and to shut state hospitals. Goldstein was instead referred to an emergency room, where he stayed overnight and was released.

Again, in July 1998, Goldstein cooperated with psychiatrists, this time during a month-long stay at Brookdale Hospital, in hopes of getting long-term care at Creedmoor. Brookdale psychiatrists had a well-documented case. In a month’s time, Goldstein committed three violent acts: punching the young woman on the subway; attacking a Brookdale therapist, a psychiatrist, a social worker and a ward aide; striking a Brookdale nurse in the face. This time, Creedmoor officials agreed in principle to take him, but explained that there was a waiting list, that they were under orders to give priority to mental patients from prison and that they did not know when they would have an opening. Days later, Goldstein was discharged from Brookdale.

520

(Winerip, 1999a)

Not only was Goldstein underserved by the mental health system, but so was the public at large. When appropriate services were available to him, Goldstein made good use of them. He spent a year in a residential setting on the grounds of the state hospital—he did well, was cooperative and friendly, and regularly took his medications. But personnel at state hospitals are under pressure to move patients to less expensive programs, even if the patients aren’t ready. Goldstein was considered too low-functioning to qualify for a program that provided less supervision, but he was discharged from the residential program nonetheless—to a home where he received almost no support. A year before the murder he tried, without success, to return to a supervised group but no spaces were available (Winerip, 1999a).

Goldstein’s history with the mental health system in New York is not unique. People with severe mental illness generally don’t receive the care they need (which is also in society’s interest for them to receive) unless their families are wealthy and willing to pay for needed services—long-term hospitalization, supervised housing, or intensive daytime supervision. Even when a defendant is deemed to be mentally ill and ordered to be transferred to a psychiatric facility, space may not be available in such a facility; the options then are to hold the defendant in jail or to release him or her and provide a less intensive form of mental health treatment (Goodnough, 2006).

As discussed in Chapter 12, deinstitutionalization is a reasonable option for those who can benefit from newer, more effective treatments, and providing treatment in the least restrictive alternative setting is also a good idea. However, such community-based forms of care are not adequately funded, which forces facilities to prioritize and provide treatment only to the sickest, leaving everyone else to make their own way. Thus, most people with severe mental illness lack adequate supervision, care, or housing. They may be living on their own in tiny rented rooms, on the street, in homeless shelters that are not equipped to handle mentally ill people, or they may be in jail. The law may mandate treatment for severely mentally ill individuals, but that doesn’t mean they receive it.

After the murder of Kendra Webdale, New York State passed Kendra’s law, allowing family members, roommates, and mental health clinicians to request court-mandated outpatient treatment for a mentally ill person who refuses treatment; a judge makes the final decision about mandating treatment. The unfortunate irony is that Goldstein sought further treatment. In his case, the real culprit may have been the lack of resources to provide the type of support and services that he and others like him—such as David Tarloff, described in Case 16.3—need.

CASE 16.3 • FROM THE OUTSIDE: A Failed Mandated Outpatient Treatment

On February 12, 2008, David Tarloff murdered psychologist Kathryn Faughey and injured psychiatrist Kent Shinbach in a delusional plan to steal money to fly to Hawaii with his elderly mother. Tarloff, who had been a patient of Shinbach, was hospitalized over a dozen times since 1991, when he was diagnosed with paranoid schizophrenia. In the year leading up to the murders, Tarloff received psychiatric care three times after violent or threatening behavior; he was stabilized on medication and released, despite his family’s request for continued inpatient treatment. After release each time, he stopped taking his medication. His family even made use of Kendra’s law, so that Tarloff was supposed to receive mandated outpatient treatment, but he avoided the periodic outpatient visits. He was released from a psychiatric unit 10 days before he murdered Faughey.

(Konigsberg & Farmer, 2008).

521

Sexual Predator Laws

People who are repeat sexual offenders—often referred to as sexual predators—are clearly dangerous. How do they fit into the legal concept of dangerousness? Are they to be treated as mentally ill? How do the criminal justice and mental health systems view such individuals?

The answers to these questions have evolved over time. Before the 1930s, a sexual offense was viewed as a criminal offense: The perpetrator was seen as able to control the behavior although he or she didn’t do so. In the 1930s, sexual offenses were viewed as related to mental illness (sexual psychopaths), and treatment programs for those who committed such offenses proliferated. Unfortunately, the treatments were not effective. By the 1980s, sexual offenses were again seen as crimes for which prison sentences were appropriate consequences. In the 1990s, after highly publicized cases of sexual mutilation and murder of children, some states passed additional laws to deal with sexually violent predators, who were seen as having no or poor ability to control their impulses. Rather than emphasizing treatment (which had not been effective), the new laws called for incarcerating these individuals as a preventative measure.

In 1997, the Supreme Court upheld the constitutionality of state laws regarding sexual predators (Kansas v. Hendricks, 1997); these laws are based on the concept of parens patriae, under which the government, as “parent,” has the power to protect the public from threats, as well as the duty to care for those who cannot take care of themselves (Perlin, 2000c). These laws were intended to prevent sex offenders from committing similar offences, in some cases by ensuring that offenders do not reenter society while there is a significant risk that they will reoffend. At the end of a prison term, if a sexual predator was deemed likely to reoffend and was suffering from a mental abnormality or personality disorder, that person could be committed to a psychiatric hospital indefinitely (Tucker & Brakel, 2012; Winick, 2003). In 2010, the Supreme Court extended such civil commitments to sexually violent predators in federal custody (United States v. Comstock, 2010).

However, some people viewed such laws as too restrictive, and in 2002, the Supreme Court ruled that in order to commit a sexual offender indefinitely after a jail or prison sentence has been served, it must be demonstrated that the person has difficulty controlling the behavior (Kansas v. Crane, 2002; the Supreme Court did not say how to demonstrate this, other than pointing to the individual’s past history). In prison, treatment is voluntary, whereas with commitment it is mandatory.

Thinking Like A Clinician

Tyrone was diagnosed with schizoaffective disorder when he was 25; his mother couldn’t supervise and take care of him to the extent that he needed. Cutbacks in mental health services in his community meant that he couldn’t receive adequate services outside of a hospital. By age 30, he was living on the streets or in jail for petty crimes such as stealing food from a grocery store, and he’d been treated for brief periods in a psychiatric facility. Based on what you have read, do you think Tyrone is dangerous—why or why not? Suppose, during psychotic episodes, he darts across busy streets—causing car accidents as drivers quickly brake to avoid hitting him. Would he legally be considered dangerous then—why or why not? What would be the advantages and disadvantages to him, and to society, of committing him to inpatient treatment? To outpatient treatment?