1.2 Preface

This is an exciting time to study psychopathology. Research on the entire range of psychological disorders has blossomed during the last several decades, producing dramatic new insights about psychological disorders and their treatments. However, the research results are outpacing the popular media’s ability to explain them. We’ve noticed that when study results are explained in a news report or an online magazine article, “causes” of mental illness are often reduced to a single factor, such as genes, brain chemistry, irrational thoughts, or social rejection. But that is not an accurate picture. Research increasingly reveals that psychopathology arises from a confluence of three types of factors: neurological (brain and body, including genes), psychological (thoughts, feelings, and behaviors), and social (relationships, communities, and culture). Moreover, these three sorts of factors do not exist in isolation, but rather mutually influence each other. It’s often tempting to seek a single cause of psychopathology, but this effort is fundamentally misguided.

We are a clinical psychologist (Rosenberg) and a cognitive neuroscientist (Kosslyn) who have been writing collaboratively for many years. Our observations about the state of the field of psychopathology—and the problems with how it is sometimes portrayed—led us to envision an abnormal psychology textbook that is guided by a central idea, which we call the neuropsychosocial approach. This approach allows us to conceptualize the ways in which neurological, psychological, and social factors interact to give rise to mental disorders. These interactions take the form of feedback loops in which each type of factor affects every other type. Take depression, for instance, which we discuss in Chapter 5: Someone who attributes the cause of a negative event to his or her own personal characteristics or behavior (such attributions are a psychological factor) is more likely to become depressed. But this tendency to attribute the cause of negative events to oneself is influenced by social experiences, such as being criticized or abused. In turn, such social factors can alter brain functioning (particularly if one has certain genes), and abnormalities in brain functioning affect one’s thoughts and social interactions, and so on—round and round.

The neuropsychosocial approach grew out of the venerable biopsychosocial approach—but instead of focusing broadly on biology, we take advantage of the bountiful harvest of findings about the brain that have filled the scientific journals over the past two decades. Specifically, the name change signals a focus on the brain itself; we derive much insight from the findings of neuroimaging studies, which reveal how brain systems function normally and how they have gone awry with mental disorders, and we also learn an enormous amount from findings regarding neurotransmitters and genetics.

Although mental disorders cannot be fully understood without reference to the brain, neurological factors alone cannot explain these disorders; rather, mental disorders develop through the complex interaction of neurological factors with psychological and social factors. Without question, psychopathology cannot be reduced to “brain disease,” akin to a problem someone might have with his or her liver or lungs. Instead, we show that the effects of neurological factors can only be understood in the context of the other two types of factors addressed within the neuropsychosocial approach. (In fact, an understanding of a psychological disorder cannot be reduced to any single type of factor, whether genetics, irrational thoughts, or family interaction patterns.) Thus, we present cutting-edge neuroscience research results and put them in context, explaining how they illuminate issues in psychopathology.

Our emphasis on feedback loops among neurological, psychological, and social factors led us to reconceptualize and incorporate the classic diathesis-stress model (which posits a precondition that makes a person vulnerable and an environmental trigger—the diathesis and stress, respectively). In the classic view, the diathesis was almost always treated as a biological state, and the stress was viewed as a result of environmental events. In contrast, after describing the conventional diathesis-stress model in Chapter 1, we explain how the neuropsychosocial approach provides a new way to think about the relationship between diathesis and stress. Specifically, we show how one can view any of the three sorts of factors as a potential source of either a diathesis or a stressor. For example, living in a dangerous neighborhood, which is a social factor, creates a diathesis for which psychological events can serve as the stressor, triggering an episode of depression. Alternatively, being born with a very sensitive amygdala (a brain structure involved in fear and other strong emotions) may act as a diathesis for which social events—such as observing someone else being mugged—can serve as a stressor that triggers an anxiety disorder.

xviii

Thus, the neuropsychosocial approach is not simply a change in terminology (“bio” to “neuro”), but rather a change in basic orientation: We do not view any one sort of factor as “privileged” over the others, but regard the interactions among the factors—the feedback loops—as paramount. In our view, this approach incorporates what was best about the biopsychosocial approach and the diathesis-stress model.

Our new approach should lead students who use this textbook to think critically about theories and research on etiology, diagnosis and treatment of mental disorders. We want students to come away from the course with the knowledge and skills to understand why no single type of findings alone can explain psychopathology, and to have compassion for people suffering from psychological disorders. One of our goals is to put a “human face” on mental illness, which we do by using case studies to illustrate and make concrete each disorder. These goals are especially important because this course will be the last psychology course many students take—and this might be the last book about psychology they read.

The new approach we have adopted led naturally to a set of unique features, as we outline next.

Unique Coverage

By integrating cutting-edge neuroscience research and more traditional psychosocial research on psychopathology and its treatment, this textbook provides students with a sense of the field as a coherent whole, in which different research methods illuminate different aspects of abnormal psychology. Our integrated neuropsychosocial approach allows students to learn not only how neurological factors affect mental processes (such as executive functions) and mental contents (such as distorted beliefs), but also how neurological factors affect emotions, behavior, social interactions, and responses to environmental events—and vice versa.

The 16 chapters included in this book span the traditional topics covered in an abnormal psychology course. The neuropsychosocial theme is reflected in both the overall organization of the text and the organization of its individual chapters. We present the material in a decidedly contemporary context that infuses both the foundational chapters (Chapters 1–4) as well as the chapters that address specific disorders (Chapters 5–15).

In Chapter 2, we provide an overview of explanations of abnormality and discuss neurological, psychological, and social factors. Our coverage is not limited merely to categorizing causes as examples of a given type of factor; rather, we explain how a given type of factor influences and creates feedback loops with other factors. Consider depression again: The loss of a relationship (social factor) can affect thoughts and feelings (psychological factors), which—given a certain genetic predisposition (neurological factor)—can trigger depression. Using the neuropsychosocial approach, we show how disparate fields of psychology and psychiatry (such as neuroscience and clinical practice) are providing a unified and overarching understanding of abnormal psychology.

xix

Our chapter on diagnosis and assessment (Chapter 3) uses the neuropsychosocial framework to organize methods of assessing abnormality. We discuss how abnormality may be assessed through measures that address the different types of factors: neurological (e.g., neuroimaging data or certain types of blood tests), psychological (e.g., clinical interviews or questionnaires), and social (e.g., family interviews or a history of legal problems).

The research methods chapter (Chapter 4) also provides unique coverage. We explain the general scientific method, but we do so within the neuropsychosocial framework. Specifically, we consider methods used to study neurological factors (e.g., neuroimaging), psychological factors (e.g., self-reports of thoughts and moods), and social factors (e.g., observational studies of dyads or groups or of cultural values and expectations). We show how the various measures themselves reflect the interactions among the different types of factors. For instance, when researchers ask participants to report family dynamics, they are relying on psychological factors—participants’ memories and impressions—to provide measures of social factors. Similarly, when researchers use the number of items checked on a stressful-life events scale to infer the actual stress experienced by a person, social factors provide a proxy measure of the psychological and neurological consequences of stress. We also discuss research on treatment from the neuropsychosocial framework.

The clinical chapters (Chapters 5–15), which address specific disorders, also rely on the neuropsychosocial approach to organize the discussions of both etiology and treatment of the disorders. Moreover, when we discuss a particular disorder, we address the three basic questions of psychopathology: What exactly constitutes this psychological disorder? What neuropsychosocial factors are associated with it? How is it treated?

Pedagogy

All abnormal psychology textbooks cover a lot of ground: Students must learn many novel concepts, facts, and theories. We want to make that task easier, to help students come to a deeper understanding of what they learn and to consolidate that material effectively. The textbook uses a number of pedagogical tools to achieve this goal.

Feedback Loops Within the Neuropsychosocial Approach

This textbook highlights and reinforces the theme of feedback loops among neurological, psychological, and social factors in several ways:

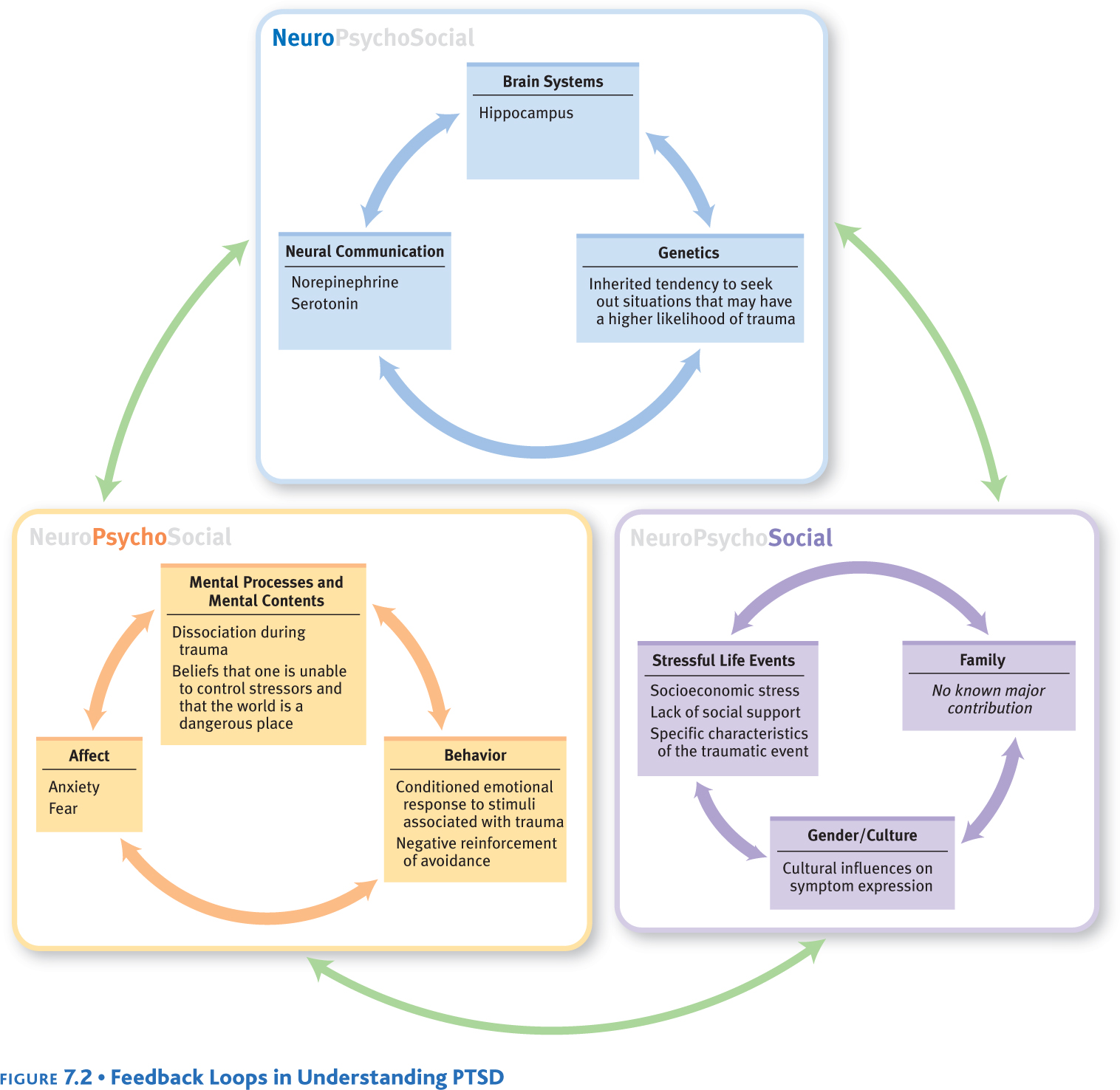

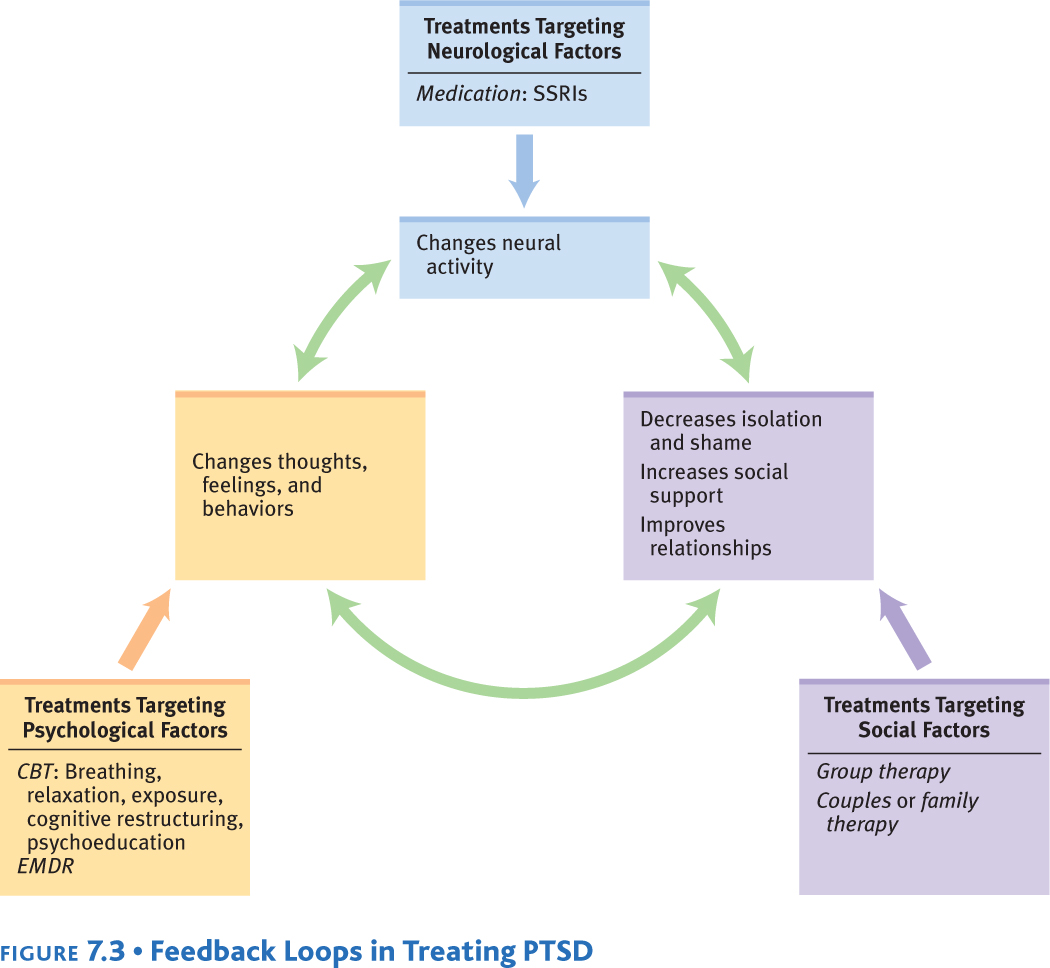

- In each clinical chapter, we include a section on “Feedback Loops in Understanding,” which specifically explores how disorders result from interactions among the neuropsychosocial factors. We also include a section on “Feedback Loops in Treating,” which specifically explores how successful treatment results from interactions among the neuropsychosocial factors.

- We include neuropsychosocial “Feedback Loop” diagrams as part of these sections. For example, in Chapter 7 we provide a Feedback Loop diagram for understanding posttraumatic stress disorder and another for treating posttraumatic stress disorder. These diagrams illustrate the feedback loops among the neurological, psychological, and social factors. Additional feedback loop diagrams can be found on the book’s website at: www.worthpublishers.com/launchpad/rkabpsych2e.

xx

- The Feedback Loops in Understanding diagrams serve several purposes: (1) they provide a visual summary of the most important neuropsychosocial factors that contribute to various disorders; (2) they illustrate the interactive nature of the factors; (3) because their overall structure is the same for each disorder, students can compare and contrast the specifics of the feedback loops across disorders.

xxi

- Like the Feedback Loops in Understanding diagrams, the Feedback Loops in Treating diagrams serve several purposes: (1) they provide a visual summary of the treatments for various disorders; (2) they illustrate the interactive nature of successful treatment (the fact that a treatment may directly target one type of factor, but changes in that factor in turn affect other factors); (3) because their overall structure is the same for each disorder, students can compare and contrast the specifics of the feedback loops across disorders.

Clinical Material

Abnormal psychology is a fascinating topic, but we want students to go beyond fascination; we want them to understand the human toll of psychological disorders—what it’s like to suffer from and cope with such disorders. To do this, we’ve incorporated several pedagogical elements. The textbook includes three types of clinical material: chapter stories—each chapter has a story woven through, traditional third-person cases (From the Outside), and first-person accounts (From the Inside).

Chapter Stories: Illustration and Integration

Each chapter opens with a story about a person (or, in some cases, several people) who has symptoms of psychological distress or dysfunction. Observations about the person or people are then woven throughout the chapter. These chapter stories illustrate the common threads that run throughout the chapter (and thereby integrate the material), serve as retrieval cues for later recall of the material, and show students how the theories and research presented in each chapter apply to real people in the real world; the stories humanize the clinical descriptions and discussions of research presented in the chapters.

xxii

The chapter stories present people as clinicians and researchers often find them—with sets of symptoms in context. It is up to the clinician or researcher to make sense of the symptoms, determining which of them may meet the criteria for a particular disorder, which may indicate an atypical presentation, and which may arise from a comorbid disorder. Thus, we ask the student to see situations from the point of view of clinicians and researchers, who must sift through the available information to develop hypotheses about possible diagnoses and then obtain more information to confirm or disconfirm these hypotheses.

In the first two chapters, the opening story is about a mother and daughter—Big Edie and Little Edie Beale—who were the subject of a famous documentary in the 1970s and whose lives have been portrayed more recently in the play and HBO film Grey Gardens. In these initial chapters, we offer a description of the Beales’ lives and examples of their very eccentric behavior to address two questions central to psychopathology: How is abnormality defined? Why do psychological disorders arise?

The stories in subsequent chapters focus on different examples of symptoms of psychological disorders, drawn from the lives of other people. For example, in Chapter 6 we discuss football star Earl Campbell (who suffered from symptoms of anxiety); in Chapter 7 we discuss the reclusive billionaire Howard Hughes (who suffered from symptoms of obsessive-compulsive disorder and who experienced multiple traumatic events); and in Chapter 12 we discuss the Genain quadruplets—all four of whom were diagnosed with schizophrenia.

We return often to these stories throughout each chapter in an effort to illustrate the complexity of mental disorders and to show the human side of mental illness, how it can affect people throughout a lifetime, rather than merely a moment in time.

From the Outside

The feature called From the Outside provides third-person accounts (typically case presentations by mental health clinicians) of disorders or particular symptoms of disorders. These accounts provide an additional opportunity for memory consolidation of the material (because they mention symptoms the person experienced), an additional set of retrieval cues, and a further sense of how symptoms and disorders affect real people; these cases also serve to expose students to professional case material. The From the Outside feature covers an array of disorders, such as cyclothymic disorder, panic disorder, transvestic disorder, and separation anxiety disorder. Often several From the Outside cases are included in a chapter.

From the Inside

In every chapter in which we address a disorder in depth, we present at least one first-person account of what it is like to live with that disorder or particular symptoms of it. In addition to providing high-interest personal narratives, these From the Inside cases help students to consolidate memory of the material, provide additional retrieval cues, and are another way to link the descriptions of disorders and research findings to real people’s experiences. The From the Inside cases illuminate what it is like to live with disorders such as agoraphobia, obsessive-compulsive disorder, illness anxiety disorder, alcohol use disorder, gender dysphoria, and schizophrenia, among others.

xxiii

Learning About Disorders: Consolidated Tables to Consolidate Learning

In the clinical chapters, we provide two types of tables to help students organize and consolidate information related to diagnosis: DSM-5 diagnostic criteria tables, and Facts at a Glance tables.

DSM-5 Diagnostic Criteria Tables

The American Psychiatric Association’s manual of psychiatric disorders—the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition (DSM-5)—provides tables of the diagnostic criteria for each of the listed disorders. For each disorder that we discuss at length, we present the DSM-5 diagnostic criteria table; we also explain and discuss the criteria—and criticisms of them—in the body of the chapters themselves.

Facts at a Glance Tables for Disorders

Another important innovation is our summary tables for each disorder, which provide key facts about prevalence, comorbidity, onset, course, and gender and cultural factors. These tables are clearly titled with the name of the disorder, which is followed by the term “Facts at a Glance” (for instance, Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder Facts at a Glance). These tables give students the opportunity to access this relevant information in one place and to compare and contrast the facts for different disorders.

New Features

This edition has two new features: Current Controversy boxes and Getting the Picture critical thinking photo sets.

Current Controversies

New to this edition, each clinical chapter includes a brief discussion about a current controversy related to a disorder—its diagnosis or its treatment. Examples include whether the new diagnoses in DSM-5 of mild and major neurocognitive disorders are net positive or negative changes from DSM-IV, and whether eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) provides additional benefit beyond that of other treatments for posttraumatic stress disorder. These discussions help students understand the iterative and sometimes controversial nature of classifying “problems” and symptoms as disorders, and whether and when treatments might be appropriate. Many of these discussions were contributed by instructors who teach Abnormal Psychology—including: Ken Abrams, Carleton College; Randy Arnau, University of Southern Mississippi; Glenn Callaghan, San Jose State University; Richard Conti, Kean University; Patrice Dow-Nelson, New Jersey City University; James Foley, College of Wooster; Rick Fry, Youngstown State University; Farrah Hughes, Francis Marion University; Meghana Karnik-Henry, Green Mountain College; Kevin Meehan, Long Island University; Jan Mendoza, Golden West College; Meera Rastogi, University of Cincinnati, Clermont College; Harold Rosenberg, Bowling Green State University; Anthony Smith, Baybath College; and Janet Todaro, Salem State University.

Getting the Picture

GETTING THE PICTURE

© PhotoAlto sas/Alamy

Also new to this edition are brief visual features that help to consolidate learning, which we call Getting the Picture: We offer two photos and ask students to decide which one best illustrates a clinical phenomenon described in the chapter. Each chapter contains several of these features.

xxiv

Summarizing and Consolidating

We include two more key features to help students learn the material: end-of-section application exercises and end-of-chapter summaries (called Summing Up).

{em}Thinking Like a Clinician{/em}: End-of-Section Application Exercises

At the end of each major section in the clinical chapters, we provide Thinking Like a Clinician questions. These questions ask students to apply what they have learned to other people and situations. These questions allow students to test their knowledge of the chapter’s material; they may be assigned as homework or used to foster small-group or class discussion.

End-of-Chapter Review: {em}Summing Up{/em}

The end-of-chapter review is designed to help students further consolidate the material in memory:

- Section Summaries: These summaries allow students to review what they have learned in the broader context of the entire chapter’s material.

- Key Terms: At the end of each chapter we list the key terms used in that chapter—the terms that are presented in boldface in the text and are defined in the marginal glossaries—with the pages where the definitions can be found.

- At the very end of Summing Up, students are directed to the online study aids and resources pertinent to the chapter.

Integrated Gender and Cultural Coverage

We have included extensive culture and gender coverage, and integrated it throughout the entire textbook. You’ll find a complete list of this coverage on the book’s catalog page. Some of our coverage of culture and gender include:

- Facts at a Glance tables provide relevant cultural and gender data for each specific disorder

- Cultural differences in evaluating symptoms of disorders in psychological research, 63, 66

- Cultural differences in assessing social factors in psychological assessment, 75, 103–104

- Gender and cultural consideration in depressive disorders, 127

- Suicide—cultural factors, 150

- Cultural influence of substance abuse, 263

- Alcoholism rate variations by gender and culture, 271–273, 411

- Gender and culture differences in schizophrenia, 377

- Oppositional defiant disorder—cultural considerations for diagnosis, 468

- Gender differences in different types of dementia (TABLE 15.9), 501

Media and Supplements

The second edition of our book features a wide array of multimedia tools designed to meet the needs of both students and teachers. For more information about any of the items below, visit Worth Publishers’ online catalog at www.worthpublishers.com.

LAUNCHPAD WITH LEARNINGCURVE QUIZZING A comprehensive Web resource for teaching and learning psychology, LaunchPad combines rich media resources and an easy-to-use platform. For students, it is the ultimate online study guide with videos, e-Book, and the LearningCurve adaptive quizzing system. For instructors, LaunchPad is a full course space where class documents can be posted, quizzes are easily assigned and graded, and students’ progress can be assessed and recorded. The LaunchPad for our second edition can be previewed at: www.worthpublishers.com/launchpad/rkabpsych2e. You’ll find the following in our LaunchPad:

The LearningCurve quizzing system was designed based on the latest findings from learning and memory research. It combines adaptive question selection, immediate and valuable feedback, and a game-like interface to engage students in a learning experience that is unique to them. Each LearningCurve quiz is fully integrated with other resources in LaunchPad through the Personalized Study Plan, so students will be able to review with Worth’s extensive library of videos and activities. State-of-the-art question analysis reports allow instructors to track the progress of individual students as well as the class as a whole. The many questions in LearningCurve have been prepared by a talented team of instructors including Kanoa Meriwether from the University of Hawaii, West Oahu, Danielle Gunraj from the State University of New York at Binghamton, and Anna Aulette Root from the University of Capetown.

- Diagnostic Quizzing developed by Diana Joy of Denver Community College and Judith Levine from Farmingdale State College includes more than 400 questions for every chapter that help students identify their areas of strength and weakness.

- An interactive e-Book allows students to highlight, bookmark, and make their own notes, just as they would with a printed textbook. Digital enhancements include full-text search and in-text glossary definitions.

xxvi

- Student Video Activities include more than 60 engaging and gradeable video activities, including archival footage, explorations of current research, case studies, and documentaries.

- The Scientific American Newsfeed delivers weekly articles, podcasts, and news briefs on the very latest developments in psychology from the first name in popular science journalism.

COURSESMART E-BOOK The CourseSmart e-Book offers the complete text in an easy-to-use, flexible format. Students can choose to view the CourseSmart e-Book online or download it to a personal computer or a portable media player, such as a smart phone or iPad. The CourseSmart e-Book for Abnormal Psychology, Second Edition, can be previewed and purchased at www.coursesmart.com.

Also Available for Instructors

The Abnormal Psychology video collection on Flash Drive and DVD. This comprehensive collection of more than 130 videos includes a balanced set of cases, experiments, and current research clips. Instructors can play clips to introduce key topics, to illustrate and reinforce specific core concepts, or to stimulate small-group or full-classroom discussions. Clips may also be used to challenge students’ critical thinking skills—either in class or via independent, out-of-class assignments.

INSTRUCTOR’S RESOURCE MANUAL, by Kanoa Meriwether, University of Hawaii, West Oahu and Meera Rastogi, University of Cincinnati: The manual offers chapter-by-chapter support for instructors using the text, as well as tips for explaining to students the neuropsychosocial approach to abnormal psychology. For each chapter, the manual offers a brief outline of learning objectives and a list of key terms. In addition, it includes a chapter guide, including an extended chapter outline, point-of-use references to art in the text, and listings of class discussions/activities, assignments, and extra-credit projects for each section.

xxvii

TEST BANK, by James Rodgers from Hawkeye Community College, Joy Crawford, University of Washington, and Judith Levine, Farmingdale State College: The test bank offers over 1700 questions, including multiple-choice, true/false, fill-in, and essay questions. The Diploma-based CD version makes it easy for instructors to add, edit, and change the order of questions.

PRESENTATION SLIDES are available in three formats that can be used as they are or can be customized. One set includes all the textbook’s illustrations and tables. The second set consists of lecture slides that focus on key themes and terms in the book and include text illustrations and tables. A third set of PowerPoint slides provides an easy way to integrate the supplementary video clips into classroom lectures. In addition, we have lecture outline slides correlated to each chapter of the book created by Pauline Davey Zeece from University of Nebraska-Lincoln.

Acknowledgments

We want to thank the following people, who generously gave of their time to review one or more—in some cases all—of the chapters in this book. Their feedback has helped make this a better book.

REVIEWERS OF THE FIRST EDITION

- Eileen Achorn, University of Texas at San Antonio

- Tsippa Ackerman, Queens College

- Paula Alderette, University of Hartford

- Richard Alexander, Muskegon Community College

- Leatrice Allen, Prairie State College

- Liana Apostolova, University of California, Los Angeles

- Hal Arkowitz, University of Arizona

- Randolph Arnau, University of Southern Mississippi

- Tim Atchison, West Texas A&M University

- Linda Bacheller, Barry University

- Yvonne Barry, John Tyler Community College

- David J. Baxter, University of Ottawa

- Bethann Bierer, Metropolitan State College of Denver

- Dawn Bishop Mclin, Jackson State University

- Nancy Blum, California State University, Northridge

- Robert Boland, Brown University

- Kathryn Bottonari, University at Buffalo/SUNY

- Joan Brandt Jensen, Central Piedmont Community College

- Franklin Brown, Eastern Connecticut State University

- Eric Bruns, Campbellsville University

- Gregory Buchanan, Beloit College

- Jeffrey Buchanan, Minnesota State University–Mankato

- NiCole Buchanan, Michigan State University

- Danielle Burchett, Kent State University

- Glenn M. Callaghan, San Jose State University

- Christine Calmes, University at Buffalo/SUNY

- Rebecca Cameron, California State University, Sacramento

- Alastair Cardno, University of Leeds

- Kan Chandras, Fort Valley State University

- Jennifer Cina, University of St. Thomas

- Carolyn Cohen, Northern Essex Community College

- Sharon Cool, University of Sioux Falls

- Craig Cowden, Northern Virginia Community College

- Judy Cusumano, Jefferson College of Health Sciences

- Daneen Deptula, Fitchburg State College

- Dallas Dolan, The Community College of Baltimore County

- Mitchell Earleywine, University at Albany/SUNY

- Christopher I. Eckhardt, Purdue University

- Diane Edmond, Harrisburg Area Community College

- James Eisenberg, Lake Erie College

- Frederick Ernst, University of Texas–Pan American

- John P. Garofalo, Washington State University–Vancouver

- Franklin Foote, University of Miami

- Sandra Jean Foster, Clark Atlantic University

- Richard Fry, Youngstown State

- Murray Fullman, Nassau Community College

- Irit Gat, Antelope Valley College

- Marjorie Getz, Bradley University

- Andrea Goldstein, South University

- Steven Gomez, Harper College

- Carol Globiana, Fitchburg State University

- Cathy Hall, East Carolina University

- Debbie Hanke, Roanoke Chowan Community College

- Sheryl Hartman, Miami Dade College

- Wanda Haynie, Greenville Technical College

- Brian Higley, University of North Florida

- Debra Hollister, Valencia Community College

- Kris Homan, Grove City College

- Farrah Hughes, Francis Marion University

- Kristin M. Jacquin, Mississippi State University

- Annette Jankiewicz, Iowa Western Community College

- Paul Jenkins, National University

- Cynthia Kalodner, Towson University

- Richard Kandus, Mt. San Jacinto College

- Jason Kaufman, Inver Hills Community College

- Jonathan Keigher, Brooklyn College

- Mark Kirschner, Quinnipiac University

- Cynthia Kreutzer, Georgia Perimeter College, Clarkston

- Thomas Kwapil, University of North Carolina at Greensboro

- Kristin Larson, Monmouth College

- Dean Lauterbach, Eastern Michigan University

- Robert Lichtman, John Jay College of Criminal Justice

- Michael Loftin, Belmont University

- Jacquelyn Loupis, Rowan-Cabarrus Community College

- Donald Lucas, Northwest Vista College

- Mikhail Lyubansky, University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign

- Eric J. Mash, University of Calgary

- Janet Matthews, Loyola University

- Dena Matzenbacher, McNeese State University

- Timothy May, Eastern Kentucky University

- Paul Mazeroff, McDaniel University

- Dorothy Mercer, Eastern Kentucky University

- Paulina Multhaupt, Macomb Community College

- Mark Nafziger, Utah State University

- Craig Neumann, University of North Texas

- Christina Newhill, University of Pittsburgh

- Bonnie Nichols, Arkansas NorthEastern College

- Rani Nijjar, Chabot College

- Janine Ogden, Marist College

- Randall Osborne, Texas State University–San Marcos

- Patricia Owen, St. Mary’s University

- Crystal Park, University of Connecticut

- Karen Pfost, Illinois State University

- Daniel Philip, University of North Florida

- Skip Pollack, Mesa Community College

- William Price, North Country Community College

- Linda Raasch, Normandale Community College

- Christopher Ralston, Grinnell College

- Lillian Range, Our Lady of Holy Cross College

- Judith Rauenzahn, Kutztown University

- Jacqueline Reihman, State University of New York at Oswego

- Sean Reilley, Morehead State University

- David Richard, Rollins College

- Harvey Richman, Columbus State University

- J.D. Rodgers, Hawkeye Community College

- David Romano, Barry University

- Sandra Rouce, Texas Southern University

- David Rowland, Valparaiso University

- Lawrence Rubin, St. Thomas University

- Stephen Rudin, Nova Southeastern University

- Michael Rutter, Canisius College

- Thomas Schoeneman, Lewis and Clark College

- Stefan E. Schulenberg, University of Mississippi

- Christopher Scribner, Lindenwood University

- Russell Searight, Lake Superior State University

- Daniel Segal, University of Colorado at Colorado Springs

- Frances Sessa, Pennsylvania State University, Abington

- Fredric Shaffer, Truman State University

- Eric Shiraev, George Mason University

- Susan J. Simonian, College of Charleston

- Melissa Snarski, University of Alabama

- Jason Spiegelman, Community College of Beaver County

- Michael Spiegler, Providence College

- Barry Stennett, Gainesville State College

- Carla Strassle, York College of Pennsylvania

- Nicole Taylor, Drake University

- Paige Telan, Florida International University

- Carolyn Turner, Texas Lutheran University

- MaryEllen Vandenberg, Potomac State College of West Virginia

- Elaine Walker, Emory University

- David Watson, MacEwan University

- Karen Wolford, State University of New York at Oswego

- Shirley Yen, Brown University

- Valerie Zurawski, St. John’s University

- Barry Zwibelman, University of Miami

REVIEWERS OF THE SECOND EDITION

- Mildred Cordero, Texas State University

- Brenda East, Durham Technical Community College

- Jared F. Edwards, Southwestern Oklahoma State University

- Rick Fry, Youngstown State University

- Kelly Hagan, Bluegrass Community & Technical College

- Jay Kosegarten, Southern New Hampshire University

- Katherine Lau, University of New Orleans

- Linda Lelii, St. Josephs University

- Tammy L. Mahan, College of the Canyons

- David McAllister, Salem State University

- Kanoa Meriwether, University of Hawaii, West Oahu

- Bryan Neighbors, Southwestern University

- Katherine Noll, University of Illinois-Chicago

- G. Michael Poteat, East Carolina University

- Kimberly Renk, University of Central Florida

- JD Rodgers, Hawkeye Community College

- Eric Rogers, College of Lake County

- Ty S. Schepis, Southwest Texas State University

- Gwendolyn Scott-Jones, Delaware State University

- Jason Shankle, Community College of Denver

- Jeff Sinkele, Anderson University

- Marc Wolpoff, Riverside Community College

xxxi

Many thanks also go to our Advisory Board for the helpful insights and suggestions:

- Randy Arnau, University of Southern Mississippi

- Carolyn Cohen, Northern Essex Community College

- Christopher Dyszelski, Madison Area Technical College

- Brenda East, Durham Technical Community College

- Rick Fry, Youngstown State University

- Jeff Henriques, University of Wisconsin

- Katherine Noll, University of Illinois at Chicago

- Marilee Ogren, Boston College

- Linda Raasch, Normandale Community College

- Judith Rauenzahn, Kutztown University

- Susan Simonian, College of Charleston

For double checking our DSM-5 information, we want to give a loud shout out of thanks to:

- Rosemary McCullough, New England Counseling Associates

- Jim Foley, College of Wooster

Although our names are on the title page, this book has been a group effort. Special thanks to a handful of people who did armfuls of work in the early stages of bringing the book to life in the first edition: Nancy Snidman, Children’s Hospital Boston, for help with the chapter on developmental disorders; Shelley Greenfield, McLean Hospital, for advice about the etiology and treatment of substance abuse; Adam Kissel, for help in preparing the first draft of some of the manuscript; Lisa McLellan, senior development editor, for conceiving the idea of “Facts at a Glance” tables; Susan Clancy for help in gathering relevant literature; and Lori Gara-Matthews and Anne Perry for sharing a typical workday of a pediatrician and a school psychologist, respectively.

To the people at Worth Publishers who have helped us bring this book from conception through gestation and birth, many thanks for your wise counsel, creativity, and patience. Specifically, for the second edition, thanks to: Jessica Bayne, our acquisitions editor and rock; Thomas Finn, our development editor who went over and over and over each chapter with good humor, patience, and a needed “outside” eye; Jim Strandberg, our pre-development editor, whose advice, support, and amazing attention to detail were sorely appreciated; Christine Cervoni and her crew at TSI Graphics for getting the manuscript ready to become a book; Babs Reingold (again), art director, for her out-of-the-box visual thinking. We’d also like to thank Roman Barnes and Robin Fadool for their help with photo research; Eileen Lang and Catherine Michaelsen for helping prepare the manuscript for turnover; Anthony Casciano for helping to wrangle our supplements and media packages; and Kate Nurre for marketing our book. And a special note of thanks to Carlise Stembridge for organizing and helping us with our advisory board.

On the personal side, we’d like to thank our children—Neil, David, and Justin—for their unflagging love and support during this project and for their patience with our foibles and passions. We also want to thank: our mothers—Bunny and Rhoda—for allowing us to know what it means to grow up with supportive and loving parents; Steven Rosenberg, for numerous chapter story suggestions; Merrill Mead-Fox, Melissa Robbins, Jeanne Serafin, Amy Mayer, Kim Rawlins, and Susan Pollak, for sharing their clinical and personal wisdom over the last three decades; Michael Friedman and Steven Hyman, for answering our esoteric pharmacology questions; and Jennifer Shephard and Bill Thompson, who helped track down facts and findings related to the neurological side of the project.

Robin S. Rosenberg

Stephen M. Kosslyn

xxxii

xxxiii