Turbulent Times: Election and Rebellion

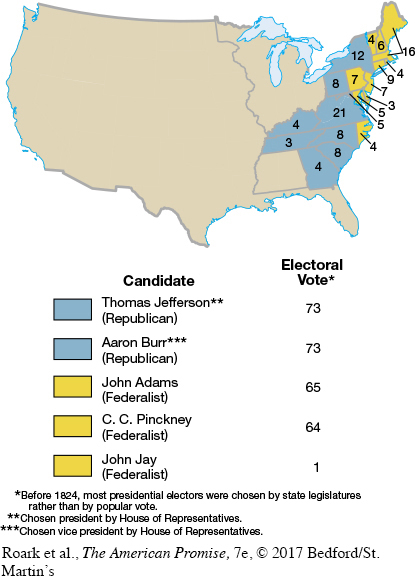

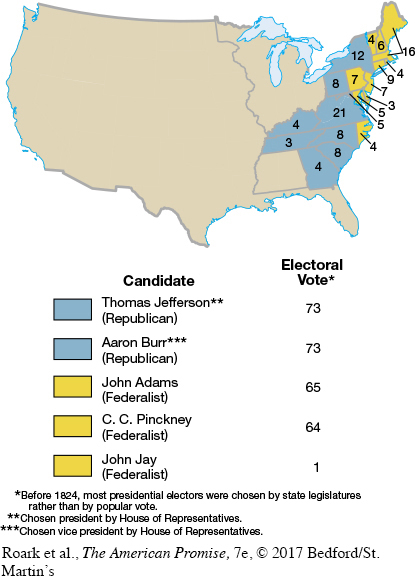

Map 10.1 The Election of 1800

The election of 1800 (Map 10.1) was historic for procedural reasons: It was the first election to be decided by the House of Representatives. Probably by mistake, Republican voters in the electoral college gave Jefferson and his running mate Senator Aaron Burr of New York an equal number of votes, an outcome possible because of the single balloting to choose both president and vice president. (To fix this problem, the Twelfth Amendment to the Constitution, adopted in 1804, provided for distinct ballots for the two offices.) That meant that the House had to choose between those two men, leaving the Federalist candidate, John Adams, out of the race. The vain and ambitious Burr declined to concede, so the sitting Federalist-dominated House of Representatives, in its waning days in early 1801, got to choose the president.

Some Federalists preferred Burr, believing that his character flaws made him susceptible to Federalist pressure. But the influential Alexander Hamilton, though no friend of Jefferson, recognized that the high-strung Burr would be more dangerous in the presidency. Jefferson was a “contemptible hypocrite” in Hamilton’s opinion, but at least he was not corrupt. (In 1804, Burr shot and killed Hamilton in a formal but illegal duel. See “Making Historical Arguments: How Could a Vice President Get Away with Murder?”)

Thirty-six ballots and six days later, Jefferson got the votes he needed to win the presidency. This election demonstrated a remarkable feature of the new government: No matter how hard fought the campaign, the leadership of the nation could shift from one group to its rivals in a peaceful transfer of power.

As the country struggled over its white leadership crisis, a twenty-four-year-old blacksmith named Gabriel, the slave of Thomas Prosser, plotted rebellion in Virginia. Inspired by the Haitian Revolution (see “The Haitian Revolution” in chapter 9), Gabriel was said to be organizing a thousand slaves to march on the state capital of Richmond and take the governor, James Monroe, hostage. On the appointed day, however, a few nervous slaves went to the authorities with news of Gabriel’s rebellion, and within days scores of implicated conspirators were jailed and brought to trial.

One of the jailed rebels compared himself to the most venerated icon of the early Republic: “I have nothing more to offer than what General Washington would have had to offer, had he been taken by the British and put to trial by them.” Such talk invoking the specter of a black George Washington worried white Virginians, and in the fall of 1800 twenty-seven black men were hanged for allegedly contemplating rebellion. Finally, Jefferson advised Governor Monroe to halt the hangings. “The world at large will forever condemn us if we indulge a principle of revenge,” Jefferson wrote.