Making Historical Arguments: How Could a Vice President Get Away with Murder?

256

How Could a Vice President Get Away with Murder?

On July 11, 1804, Vice President Aaron Burr shot Alexander Hamilton, the architect of the Federalist Party, in a duel on the cliffs of Weehawken, New Jersey, across the Hudson River from New York City. The pistol blast tore through a rib, demolished Hamilton’s liver, and splintered his spine. Hamilton died the next day in agonizing pain.

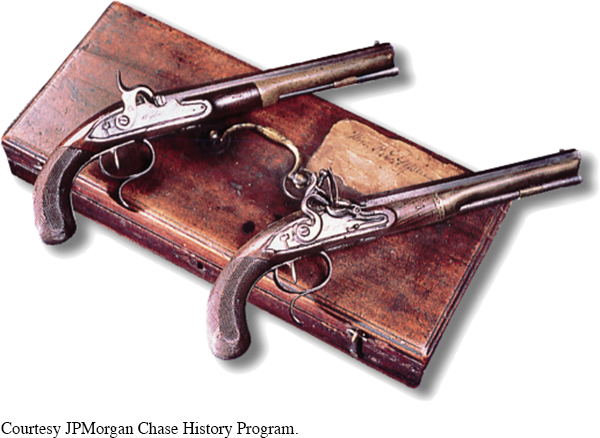

How was it that a sitting vice president and a prominent political leader could put themselves at such risk? Two eminent attorneys, skilled in the legal negotiations meant to substitute for violent resolution of disputes, fired .54-

Burr challenged Hamilton in late June after learning about a months-

Quite possibly, he was right. Suspecting that Jefferson would dump him from the federal ticket in the 1804 election, Burr decided to run for New York’s highest office. He needed the support of New York’s Federalist leadership, and he appeared to have it—

So on June 18, Burr challenged Hamilton to a duel if he did not disavow his comment. For three weeks, the men exchanged letters clarifying the nature of the insult that had aggrieved Burr. Hamilton the lawyer evasively quibbled over words, but at heart, he could neither deny the insult nor spurn the challenge without injury to his own reputation. Both Burr and Hamilton were locked in a highly ritualized procedure meant to uphold a gentleman’s code of honor.

Each man had a trusted “second,” in accord with the code of dueling, to deliver the letters and to assist at the duel. Only a handful of close friends knew of the challenge, and no one tried to stop it. Hamilton did not tell his wife. He wrote her a tender farewell letter, to be opened in the event of his death. He knew full well the pain dueling brought to loved ones, for three years earlier his nineteen-

News of Hamilton’s death spread quickly throughout the nation. New York shut down for the funeral, and the city council declared a six-

Northern newspapers expressed indignation over the illegal duel; not so in the South, where dueling was accepted as an extralegal remedy for insult. Many northern states had recently criminalized dueling, treating a challenge as a misdemeanor and a dueling death as a homicide. Even after death, the loser of an illegal duel could endure a range of penalties—

A coroner’s jury in New York soon indicted Burr on misdemeanor charges for issuing a challenge, and a grand jury in New Jersey indicted him for murder. By that time, Burr was a fugitive from justice hiding out in South Carolina.

But not for long. Amazingly, he returned to Washington, D.C., in November 1804 to resume presiding over sessions of the Senate, a role he continued to perform until his term ended in March 1805. Federalists snubbed him, but eleven Republican senators petitioned New Jersey to drop its indictment on the grounds that “civilized nations” do not treat dueling deaths as “common murders.” New Jersey did not pursue the murder charge. Burr freely visited New Jersey and New York for three more decades, paying no penalty for killing Hamilton.

Few would doubt that Burr was a scoundrel, albeit a brilliant one. A few years later, he was indicted for treason for a plot to break off part of the United States and start his own country in the Southwest. (He dodged that bullet, too.) Hamilton certainly thought Burr a scoundrel, and when that opinion reached print, Burr had cause to defend his honor under the etiquette of dueling. The accuracy of Hamilton’s charge was of no account. Dueling redressed questions of honor, not questions of fact.

Dueling held sway in the South for several more decades, but in the North the custom became extremely rare by the 1820s, discouraged by the tragedy of Hamilton’s death and by the rise of a legalistic society that now preferred evidence, interrogation, and monetary judgments to avenge injury.

Questions for Analysis

Summarize the Argument: For what injury or insult did Burr challenge Hamilton to a duel? Why did Hamilton accept?

Analyze the Evidence: Why might these men, trained as professional lawyers, go outside the law and resort to an illegal method to settle their differences?

Consider the Context: How might differences between the North and the South—