Making Historical Arguments: Did Terrorists Sink the Maine?

Did Terrorists Sink the Maine?

At 9:40 p.m. on the evening of February 15, 1898, the U.S. battleship Maine blew up in Havana harbor. “The shock threw us backward,” reported one eyewitness. “From the deck forward of amidships shot a streak of fire as high as the tall buildings on Broadway. Then the glare of light widened out like a funnel at the top, and down through this bright circle fell showers of wreckage and mangled sailors.” In all, 267 sailors drowned or burned to death in one of the worst naval catastrophes to occur during peacetime.

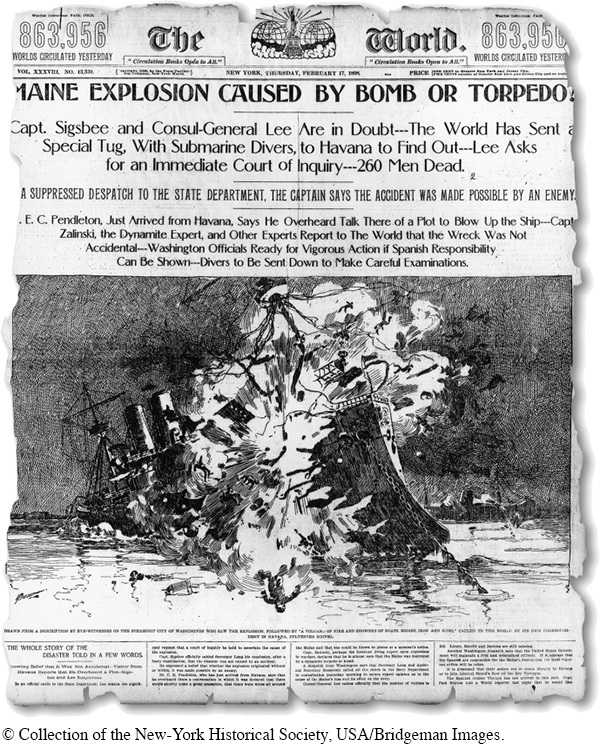

Captain Charles Dwight Sigsbee, the last man to leave the burning ship, filed a terse report saying that the Maine had blown up and “urging [that] public opinion should be suspended until further report.” But the yellow press, led by William Randolph Hearst’s New York Journal, ran banner headlines proclaiming, “The War Ship Maine Was Split in Two by an Enemy’s Secret Infernal Machine!”

Public opinion quickly divided between those who suspected foul play and those who believed the explosion had been an accident. Foremost among the accident theorists was the Spanish government, along with U.S. business interests who hoped to avoid war. The “jingoes,” as proponents of war were called, rushed to blame Spain. Even before the details were known, Assistant Secretary of the Navy Theodore Roosevelt wrote, “The Maine was sunk by an act of dirty treachery on the part of the Spaniards I believe; though we shall never find out definitely, and officially it will go down as an accident.”

In less than a week, the navy formed a court of inquiry, and divers inspected the wreckage. The panel reported on March 25, 1898, that a mine had exploded under the bottom of the ship, igniting gunpowder in the forward magazine. The panel could not determine whether the mine had been planted by the Spanish government or by recalcitrant followers of Valeriano Weyler. The infamous Weyler had been ousted after the American press dubbed him “the Butcher” for his harsh treatment of the Cubans.

As time passed, however, more people came to view the explosion of the Maine as an accident. European experts concluded that the Maine had exploded accidentally, from a fire in the coal bunker adjacent to the reserve gunpowder. Perhaps poor design, not treachery, had sunk the Maine.

In 1910, New York congressman William Sultzer put it succinctly: “The day after the ship was sunk, you could hardly find an American who did not believe that she had been foully done to death by a treacherous enemy. Today you can hardly find an American who believes Spain had anything to do with it.” The Maine still lay in the mud of Havana harbor, a sunken tomb containing the remains of many sailors. The Cuban government asked for the removal of the wreck, and veterans demanded a decent burial for the sailors. So in March 1910, Congress voted to raise the Maine and reinvestigate.

The “Final Report on Removing the Wreck of Battleship Maine from the Harbor of Habana, Cuba” appeared in April 1913. This report confirmed that the original naval inquiry was in error, but it ruled out the accident theory by concluding that the nature of the initial explosion indicated a homemade bomb—

Controversy over the Maine proved harder to sink. In the Vietnam era, when faith in the “military establishment” plummeted, Admiral Hyman Rickover launched yet another investigation. Viewing the 1913 “Final Report” as a cover-

Two decades later, the pendulum swung back. A 1995 study of the Maine published by the Smithsonian Institution concluded that zealot followers of General Weyler sank the battleship: “They had the opportunity, the means, and the motivation, and they blew up the Maine with a small low-

Questions for Analysis

Summarize the Argument: How have explanations for the sinking of the Maine changed over time? Has the evidence changed, or have interpretations of the evidence shifted?

Analyze the Evidence: Why were jingoists so quick to blame Spain for the sinking of the Maine?

Consider the Context: In 1995, the Smithsonian panel judged the sinking of the Maine a result of terrorism perpetrated by followers of the deposed General Weyler. Was their use of the word terrorism as inflammatory then as it is today?