Making Historical Arguments: Was There a Sexual Revolution in the 1920s?

660

Was There a Sexual Revolution in the 1920s?

““Cigarette in hand, shimmying to the music of the masses, the New Woman and the New Morality have made their theatric debut upon the modern scene,” lamented one commentator in 1926. The Atlantic magazine declared that a moral chasm had opened between the generations, and the old and young in America “were as far apart in point of view, codes, and standards as if they belonged to different races.” Charlotte Perkins Gilman represented many older feminists who were disappointed with the outcome of recent advances for women: “It is sickening to see so many of the newly freed abusing that freedom in a mere imitation of masculine weakness and vice.” Older Americans wholeheartedly agreed that the younger generation was in full-

661

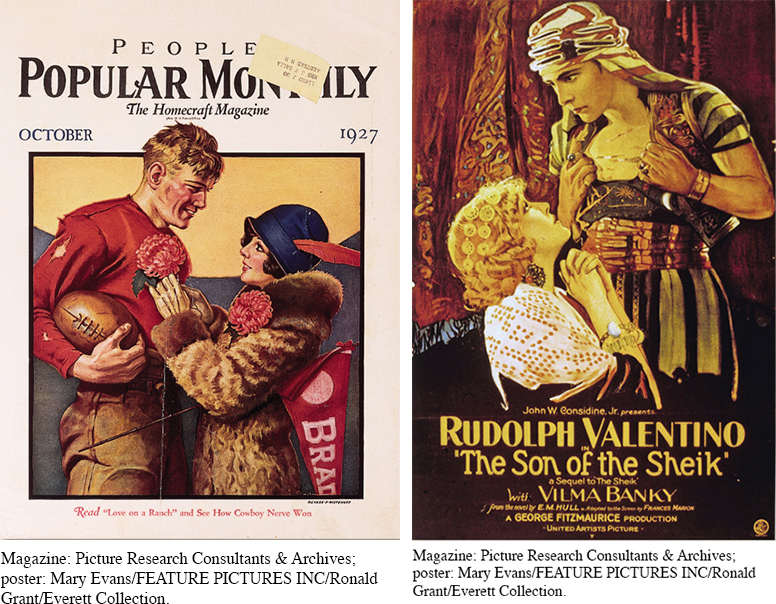

Critics had, it seemed, plenty of evidence. Between newspapers, movies, and magazines, even the small towns of America were “literally saturated with sex,” one observer complained. Flappers and college coeds claimed the privileges of men, smoking cigarettes, drinking from hip flasks, and staying out all night. When eight hundred college women met to discuss life on campus and what “nice girls” should do, they concluded, “Learn temperance in petting, not abstinence.” Anxious observers counseled intervention. The Ohio legislature debated whether to prohibit any “female over fourteen years of age” from wearing a “skirt which does not reach to that part of the foot known as the instep.” The Ladies’ Home Journal urged “legal prohibition” of jazz dancing.

But were the concerned observers correct? Was there really a sexual revolution in the 1920s? The principal movers of the new morality were youths, and without a doubt, young middle-

A good place to begin the investigation is where youth congregated: college campuses. Campus life included a self-

Like dating, petting represented a significant change in female behavior. But it was not a total rejection of traditional morality because it took place within the search for the ideal marriage partner. There was also a modest increase in premarital sexual intercourse, made possible by the widespread acceptance of contraceptives. But sexual intercourse usually took place between partners who assumed they would marry. The new woman of the 1920s, though freer sexually, continued to focus on romance, marriage, and family.

Did the new sexual behavior mark a drastic change from the past? Evidence of sexual habits before World War I is even more difficult to come by than for the 1920s, but it appears that changes in attitudes and behaviors had been under way for decades. Nineteenth-

Changes in sexual morality, therefore, were evolutionary rather than revolutionary. Still, liberal attitudes and behaviors had their greatest impact in the 1920s. American culture was being remade, and young people, especially women, were on the cutting edge. Now equal at the polling booth, women were also growing more economically independent. Changes in women’s political and economic lives were reflected in their sexual attitudes and behaviors. In place of the idea that women were naturally pure, the new morality proclaimed the equality of desire. Only the boldest women publicly rejected a “double standard” (the notion that the sexual behavior of women should be more circumscribed than that of men), but many jettisoned notions of female submission, obedience, and endless childbearing. Charges that the giddy flapper and her partner were bringing down American civilization were overblown, but young women certainly were changing the culture.

Questions for Analysis

Summarize the Argument: What is the evidence for the contention that changes in sexual behavior in the 1920s were more evolutionary than revolutionary?

Analyze the Evidence: How did changes in women’s political and economic lives affect their sexual behaviors?

Consider the Context: What was the relationship of the emergence of the “new woman” in the 1920s and the sexual habits of young women?