Experiencing the American Promise: The Quest for Home Ownership in Segregated Detroit

The Quest for Home Ownership in Segregated Detroit

Owning a place of one’s own has always been important in America. In the nineteenth century, with the rise of industry and cities, the goal of a family farm gave way to the goal of a single-family house. Home ownership has been widely realized today, with a little less than two-thirds of Americans (with the assistance of mortgage companies) owning their own homes.

In the 1920s, decent housing was in short supply in Detroit, America’s great boomtown, as thousands poured in to work in Henry Ford’s automobile factories. Arriving before World War I, blue-collar German, Irish, and Polish immigrants found homes in working-class neighborhoods scattered around the city center. The property owners resolved to keep their neighborhoods all-white by channeling the great migration of southern blacks into Black Bottom, the downtown ghetto. Although the U.S. Supreme Court had struck down a law mandating segregated housing in 1917, inventive white homeowners created other means to draw racial boundaries. Real estate agents refused to show blacks houses in white neighborhoods. Banks turned down blacks for mortgages. Whites signed restrictive covenants, promising not to sell their homes to blacks. If a black family managed to slip through their defenses, whites resorted to violence.

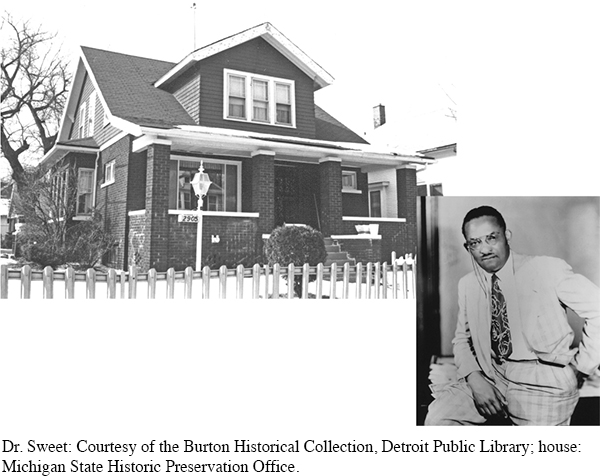

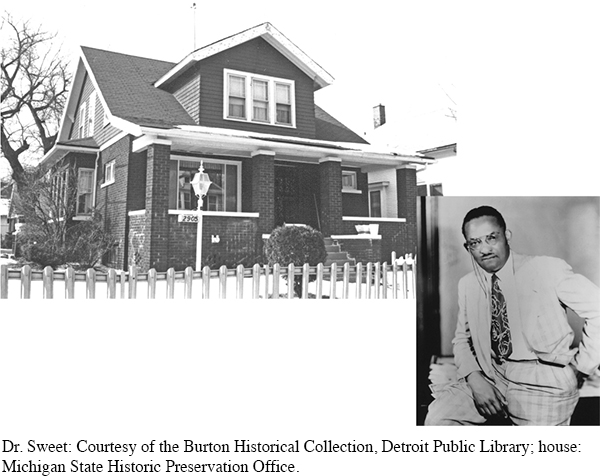

Dr. Ossian Sweet, a black physician, arrived in Detroit in 1921. He set up his medical practice in Black Bottom and prospered. He soon had the down payment for a home, but he refused to settle his wife and baby daughter in the congested, rat-infested ghetto. In 1925, Sweet bought a substantial bungalow at 2905 Garland Avenue, several blocks inside a working-class white neighborhood. His brother said later, “He wasn’t looking for trouble. He just wanted to bring up his little girl in good surroundings.” Sweet understood the danger; whites had recently run other black professionals out of their Detroit neighborhoods. “Well, we have decided we are not going to run,” Sweet told a friend. “We’re not going to look for any trouble, but we’re going to be prepared to protect ourselves if trouble arises.” When Gladys and Ossian Sweet moved into their home on September 8, 1925, nine friends and family members accompanied them. The moving van that brought their furniture also carried a shotgun, two rifles, six pistols, and four hundred rounds of ammunition.

Hundreds of white men quickly filled the streets, greatly outnumbering the few police who hoped to keep the peace. Shouting that they would send the “niggers” back where they belonged, the mob began throwing rocks, breaking windows, and advancing. Suddenly, gunfire erupted from the second story of the Sweet house, and two white men were shot; one was killed. The police kept the mob away long enough for a paddy wagon to haul the eleven blacks to the police station, where they were all indicted for murder.

Asked why he wanted to move to a white neighborhood, where there was likely to be trouble, Sweet said, “Because I bought the house, and it was my house, and I felt I had a right to live in it.” The NAACP, which saw the case as an opportunity to strike a legal blow in favor of self-defense against racial violence, hired Clarence Darrow to defend the accused. Darrow was the most celebrated defense lawyer in the country and fresh from the Scopes trial in Tennessee (see “The Scopes Trial”). Darrow told the jury that the facts were simple: “When they defended their home, they were arrested and charged with murder.” He reminded the all-white jury that “every man’s home is his castle, which even the king may not enter. Every man has a right to kill to defend himself or his family, or others, either in defense of the home, or in defense of themselves.” A split jury caused the judge to declare a mistrial. A second trial ended in not guilty verdicts for all the defendants.

Over the next several decades, blacks succeeded in breaking out of the inner cities and moving into the suburbs, where today more than one-third of African Americans live. But breaching city boundaries did not mean leaving residential segregation behind. Of all the nation’s segregated cities, none was more segregated than Detroit. As late as 1963, Martin Luther King Jr. declared: “I have a dream this afternoon that one day right here in Detroit Negroes will be able to buy a house or rent a house anywhere their money will carry them.” As for Sweet, he moved back into his home on Garland Avenue in 1928, but without his wife and daughter, both of whom had died of tuberculosis, perhaps contracted while in jail. He stayed in the bungalow for more than twenty-five years, and when he left, the neighborhood around him was still largely white.

Dr. Ossian Sweet and His House Dr. Ossian Sweet’s substantial two-story brick home is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. In September 1925, Sweet tried to move his family into the then all-white Detroit suburb where the house is located. Residents reacted violently, determined to uphold “the present high standards of the neighborhood.”

Dr. Sweet: Courtesy of the Burton Historical Collection, Detroit Public Library; house: Michigan State Historic Preservation Office.

Recognize Viewpoints: Why did whites in Sweet’s neighborhood oppose his living there?

Analyze the Evidence: Why was Clarence Darrow’s defense so effective before an all-white jury?

Consider the Context: What does the case of Ossian Sweet reveal about the aspirations of middle-class black Americans during the 1920s?