From New Era to Great Depression, 1920–1932

Printed Page 620 Chapter Chronology

From New Era to Great Depression, 1920-1932

QUICK START

Quickly learn what is important in this chapter by doing the following:

- READ the Chapter Outline to see how the chapter is organized.

- SKIM the Chronology to see what will be covered.

When you are ready, download the Guided Reading Exercise, then read the chapter and the Essential Questions for each section and complete the Guided Reading Exercise as you go. Then use LearningCurve and the Chapter Review to check what you know.

Americans in the 1920s cheered Henry Ford as an authentic American hero. When the decade began, he had already produced six million automobiles; by 1927, the figure reached fifteen million. In 1920, a Ford car cost $845; in 1928, the price was less than $300, within range of most of the country's skilled workingmen. Henry Ford put America on wheels, and in the eyes of most Americans he was an honest man who made an honest car: basic, inexpensive, and reliable.

Born in 1863 on a farm in Dearborn, Michigan, Ford at sixteen fled rural life for Detroit, where he became a journeyman machinist. His ambition, he said, was to "make something in quantity." The product he chose reflected American restlessness. "Everybody wants to be someplace he ain't," Ford declared. "As soon as he gets there he wants to go right back." In 1903, Ford gathered twelve workers in a 250-by-50-foot shed and created the Ford Motor Company.

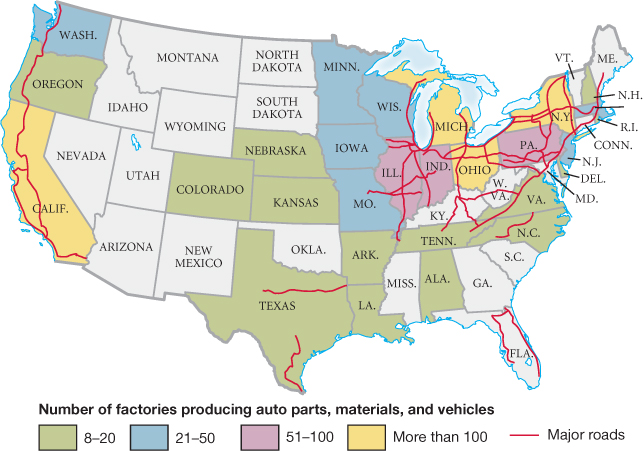

Ford's early cars were custom-made one at a time. By 1914, his cars were being built along a continuously moving assembly line. Ford made only one kind of car, the Model T, which became synonymous with mass production. Throughout the rapid expansion of the automotive industry, the Ford Motor Company remained the industry leader, peaking in 1925, when it outsold all its rivals combined (Map 23.1).

Map Activity 1 for Chapter 23

When Henry Ford began his rise, progressive critics condemned the industrial giants of the nineteenth century as "robber barons" who lived in luxury while reducing their workers to wage slaves. Ford, however, identified with the common folk and saw himself as the benefactor of average Americans. But like the age in which he lived, Henry Ford was more complex and more contradictory than this simple image suggests.

A man of genius whose compelling vision of modern mass production led the way in the 1920s, Ford was also cranky, tight-fisted, and mean-spirited. He hated Jews and Catholics, bankers and doctors, and liquor and tobacco, and his money allowed him to act on his prejudices. His automobile plants made him a billionaire, but their regimented assembly lines reduced workers to near robots. On the cutting edge of modern technology, Ford nevertheless remained nostalgic about rural values. He sought to revive the past in Greenfield Village, where he relocated buildings from a bygone era, including his parents' farmhouse. His museum contrasted sharply with the roaring Ford assembly plant at River Rouge. Yet if Americans remained true to their agrarian past and managed to be modern and scientific at the same time, Ford insisted, all would be well.

Tension between traditional values and modern conditions lay at the heart of the conflicted 1920s. For the first time, more Americans lived in urban than in rural areas, and cities seemed to harbor everything rural people opposed. While millions admired urban America's sophisticated new style and consumer products, others condemned postwar society for its loose morals and vulgar materialism. The Ku Klux Klan and other champions of an older America resorted to violence as well as words when they chastised the era's "new woman," "New Negro," and surging immigrant populations. Those who sought to dam the tide of change proposed prohibition, Protestantism, and patriotism.

The public, disillusioned with the outcome of World War I, turned away from the Christian moralism and idealism of the Progressive Era. In the 1920s, Ford and businessmen like him replaced political reformers such as Theodore Roosevelt and Woodrow Wilson as the models of progress. The U.S. Chamber of Commerce crowed, "The American businessman is the most influential person in the nation." The fortunes of the era rose, then in 1929 crashed, according to the values and practices of the business community. When prosperity collapsed, the nation entered the most serious economic depression of all time.