The Search for Other Mexicos.

Printed Page 37 Chapter Chronology

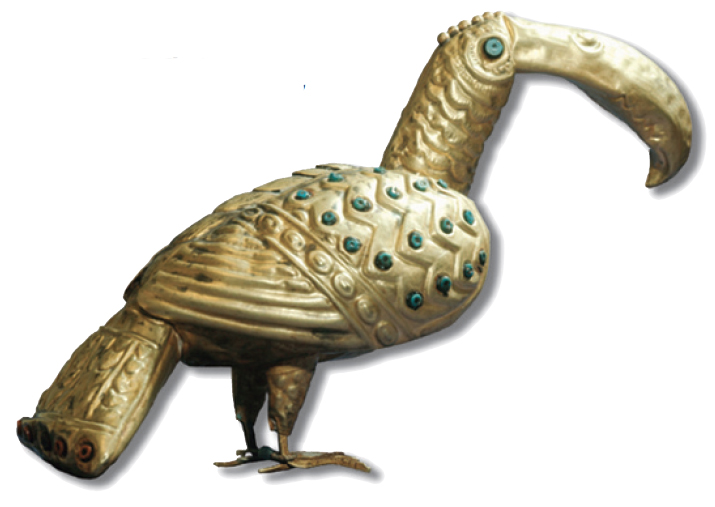

The Search for Other Mexicos. Lured by their insatiable appetite for gold, Spanish conquistadors (soldiers who fought in conquests) quickly fanned out from Tenochtitlan in search of other sources of treasure. The most spectacular prize fell to Francisco Pizarro, who conquered the Incan empire in Peru. The Incas controlled a vast, complex region that contained more than nine million people and stretched along the western coast of South America for more than two thousand miles. In 1532, Pizarro and his army of fewer than two hundred men captured the Incan emperor Atahualpa and held him hostage. As ransom, the Incas gave Pizarro the largest treasure yet produced by the conquests: gold and silver equivalent to half a century’s worth of precious-metal production in Europe. With the ransom safely in their hands, the Spaniards murdered Atahualpa. The Incan treasure proved that at least one other Mexico did indeed exist, and it spurred the Spaniards’ search for others.

conquistadors

Term, literally meaning “conqueror,” that refers to the Spanish explorers and soldiers who conquered lands in the New World.

Incan empire

A region under the control of the Incas and their emperor, Atahualpa, that stretched along the western coast of South America and contained more than nine million people and a wealth in gold and silver.

Juan Ponce de León sailed to Florida in 1521 to find riches, only to be killed in battle with Calusa Indians. A few years later, Lucas Vázquez de Ayllón explored the Atlantic coast north of Florida to present-day South Carolina. In 1526, he established a small settlement on the Georgia coast that he named San Miguel de Gualdape, the first Spanish attempt to establish a foothold in what is now the United States. This settlement was soon swept away by sickness and hostile Indians. In 1528, Pánfilo de Narváez surveyed the Gulf coast from Florida to Texas, but his expedition ended disastrously with a shipwreck near present-day Galveston, Texas.

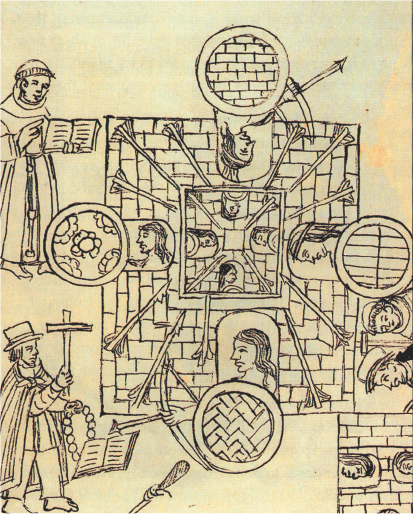

In 1539, Hernando de Soto, a seasoned conquistador, set out with more than six hundred men to find another Peru in North America. Landing in Florida, de Soto slashed his way through much of southeastern North America for three years. After brutal slaughter of many Native Americans and much hardship, de Soto died in 1542. His men buried him in the Mississippi River and turned back to Mexico, disappointed.

Tales of the fabulous wealth of the mythical Seven Cities of C'bola also lured Francisco Vásquez de Coronado to search the Southwest and Great Plains of North America. In 1540, Coronado left northern Mexico with more than three hundred Spaniards, a thousand Indians, and a priest who claimed to know the way to what he called “the greatest and best of the discoveries.” C'bola turned out to be a small Zuñi pueblo of about a hundred families. When the Zuñi shot arrows at the Spaniards, Coronado attacked the pueblo and routed the defenders after a hard battle. Convinced that the rich cities must lie somewhere over the horizon, Coronado kept moving all the way to central Kansas before deciding in 1542 that the rumors he had pursued were just that.

The same year Coronado abandoned his search for C'bola, Juan Rodr'guez Cabrillo’s maritime expedition sought to find wealth along the coast of California. Cabrillo died on Santa Catalina Island, offshore from present-day Los Angeles, but his men sailed on to Oregon, where a ferocious storm forced them to turn back toward Mexico.

These probes into North America by de Soto, Coronado, and Cabrillo persuaded other Spaniards that although enormous territories stretched northward from Mexico, their inhabitants had little to loot or exploit. After a generation of vigorous exploration, the Spaniards concluded that there was only one Mexico and one Peru.