Life in the Village

In 1999, having spent 5 years working in a hospital in Malawi, Manary took an unusual step for an American-trained doctor: he left the hospital and went to live in a rural village for 10 weeks. He wanted to get a first-hand view of the way people lived and the obstacles they faced. The thing that struck him the most was the sheer monotony of village life.

“Every day is the same,” he says. “It starts with going to the water pump, hauling water. Then it's finding firewood. Then it's cooking food.... It's work all day, 365 a year.”

Instantly, he understood why childhood malnutrition is such a terrible trap for families. Families live perilously close to the edge of sufficiency, and any slight change in their circumstances can push them over; even one extra mouth to feed can create food shortages. Moreover, for many rural populations, the nearest hospital is miles away. Taking a sick kid to the hospital is a major disruption to family life, so most mothers do it only as a last resort, when the child is already quite sick. Lastly, telling mothers—as they routinely were told by hospital doctors—that they needed to feed their malnourished child seven times a day was not a workable solution. As Manary explains, “It'd be like me telling you “Hey, you need to walk back and forth [from New York] to Connecticut every day.'” It just wasn't realistic.

Malnutrition problems usually start when children are 6 months old. Kids younger than 6 months old are sustained easily by breast-feeding alone. Breast milk is a perfect food for children at this age, explains Manary. It is nutritionally appropriate for what their bodies can handle, and it also confers protection against infections and disease. Since 2001, the World Health Organization has recommended that women breast-feed exclusively until a child is 6 months old (and they are encouraged to continue for 2 years and beyond, even after infants begin to eat other food). Virtually all women in Malawi breast-feed.

10

At 6 months, however, children's growing bodies require more nourishment than breast milk can provide, but no other food is as plentiful or accessible. Malnutrition due to chronic undereating sets in after a period of time, usually between ages 1 and 3.

Scientists sometimes refer to the first 1,000 days of life, from gestation to age 2, as the “golden interval.” “Babies go through a huge amount of physical and cognitive development during this period of 1,000 days,” says Mary Arimond, a nutrition expert at the University of California, Davis, who studies nutrition in the developing world. “If deficits occur in this “window,' they are difficult to reverse, especially in continued conditions of poverty.”

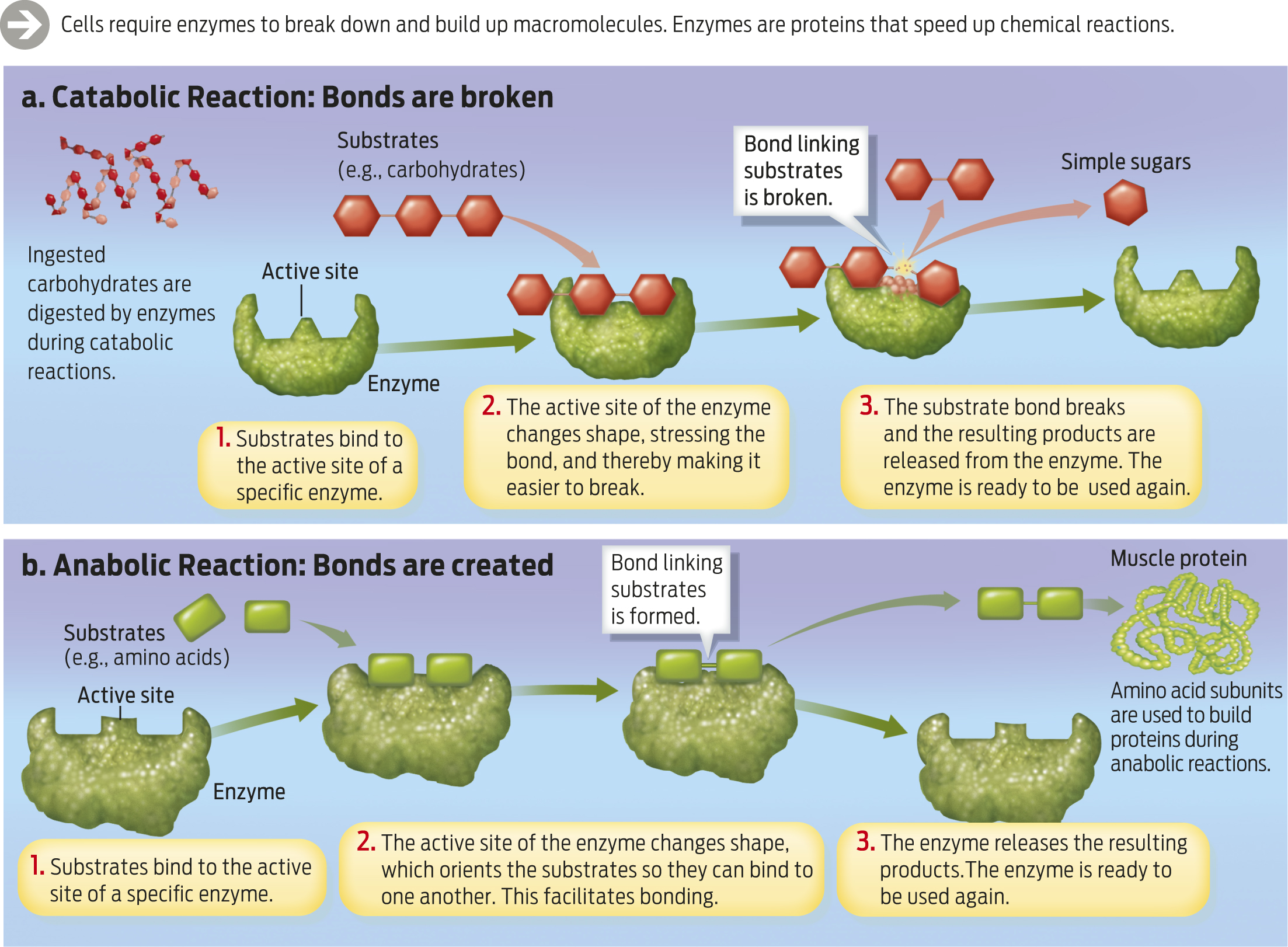

An underfed child, one that has gone without adequate nutrition for an extended period of time, will lack the raw material for growth and development. That's because growth and development are, essentially, a series of chemical reactions requiring nutrients as starting materials. These reactions begin as soon as the digestion of food begins: reactions that break down larger structures into smaller ones are called catabolic reactions. Reactions that build new structures from smaller subunits are called anabolic reactions. Together, all the chemical reactions occurring in the body constitute metabolism.

11

To proceed normally, metabolism requires the assistance of helper molecules called enzymes. Nearly every chemical reaction in the body requires enzymes. For example, digestive enzymes made by cells in the digestive tract help us digest food molecules into their constituent subunits. When cells divide—for instance in bone marrow to generate new blood cells, or in skin to replace cells lost to death or injury—they rely on a suite of enzymes to carry out a variety of processes, including copying the DNA in cells. Similarly, enzymes produced by cells in bone carry out anabolic reactions that contribute to the formation of new bone.

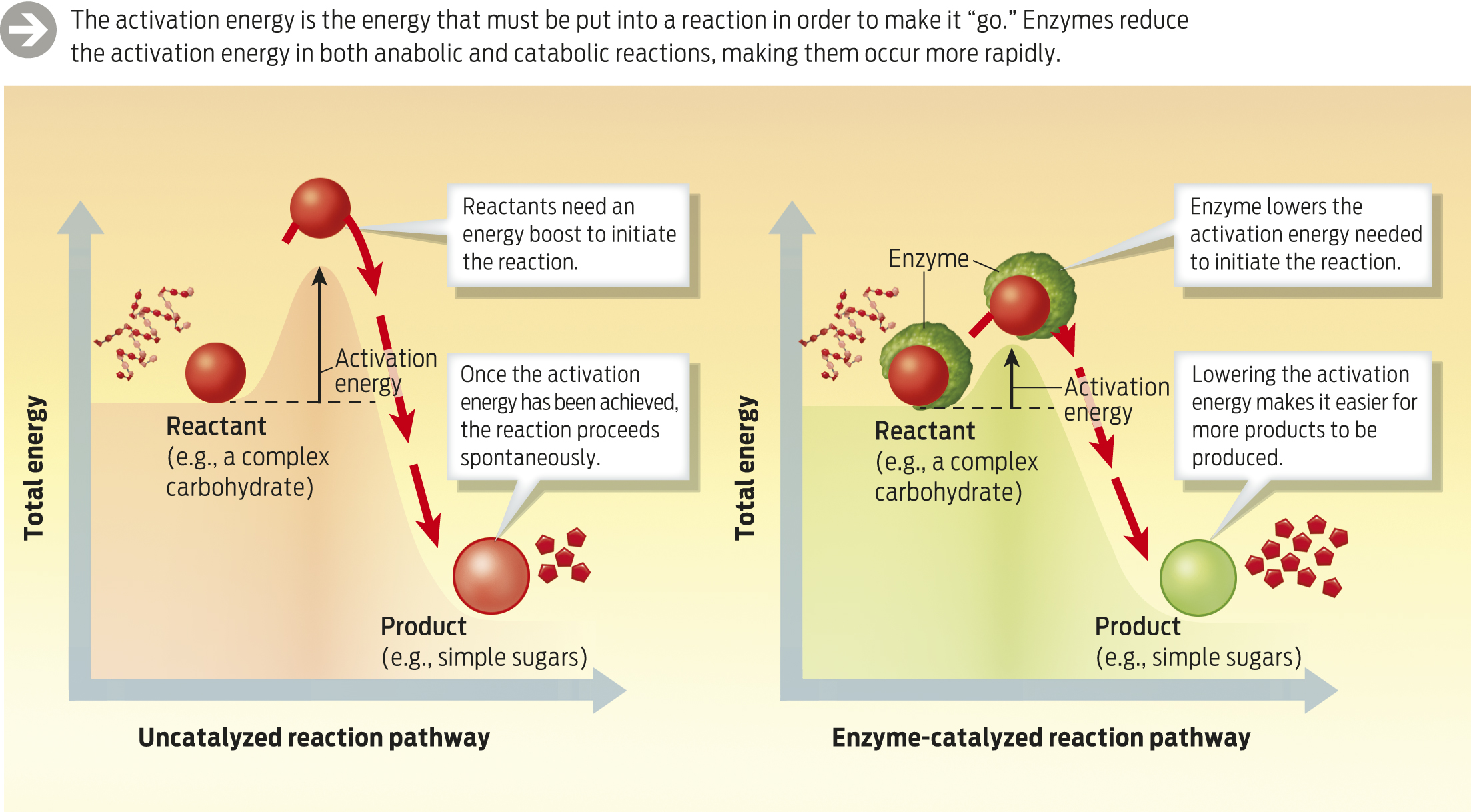

Enzymes work by speeding up, or catalyzing, chemical reactions (the process is called catalysis). In order to accelerate a reaction, the enzyme must bind to molecules involved in the reaction. The molecules that enzymes bind to are called substrates. The part of the enzyme that binds to substrates is its active site. Each enzyme has an active site that fits only one particular substrate molecule or molecules. An enzyme that breaks down carbohydrates, for example, cannot break down proteins (INFOGRAPHIC 4.4).

Enzymes catalyze reactions by lowering the amount of energy required to nudge a chemical reaction into motion. Enzymes substantially reduce this activation energy, allowing the reaction to occur more easily. For example, when complex carbohydrates are ingested, enzymes in our digestive tract help break the bonds that hold the molecules together, releasing simple sugars—a reaction that would not otherwise occur (INFOGRAPHIC 4.5).

12

Babies go through a huge amount of physical and cognitive development during this period of 1,000 days.

—MARY ARIMOND

If a child doesn't get enough to eat, the enzymes that carry out the anabolic reactions necessary for growth do not have substrates to act on, so these anabolic reactions do not occur. In fact, catabolic reactions often begin to break down existing structures—for example, muscle protein—to obtain amino acids. The results are the telltale signs of malnutrition: thin arms with skin wrinkling over wasted muscle; painful swelling of the legs and feet caused by a buildup of fluid; blond or rust-colored hair resulting from a deficiency of protein; and a distended, bloated stomach, a sign of nutrient deficiency.

Because a healthful diet requires a balance of many different kinds of nutrients, it's not only the sheer quantity of food that is important, but also the specific type of food that matters. Some nutrients can be missing from a diet, even if a child is well fed.