SIZE MATTERS

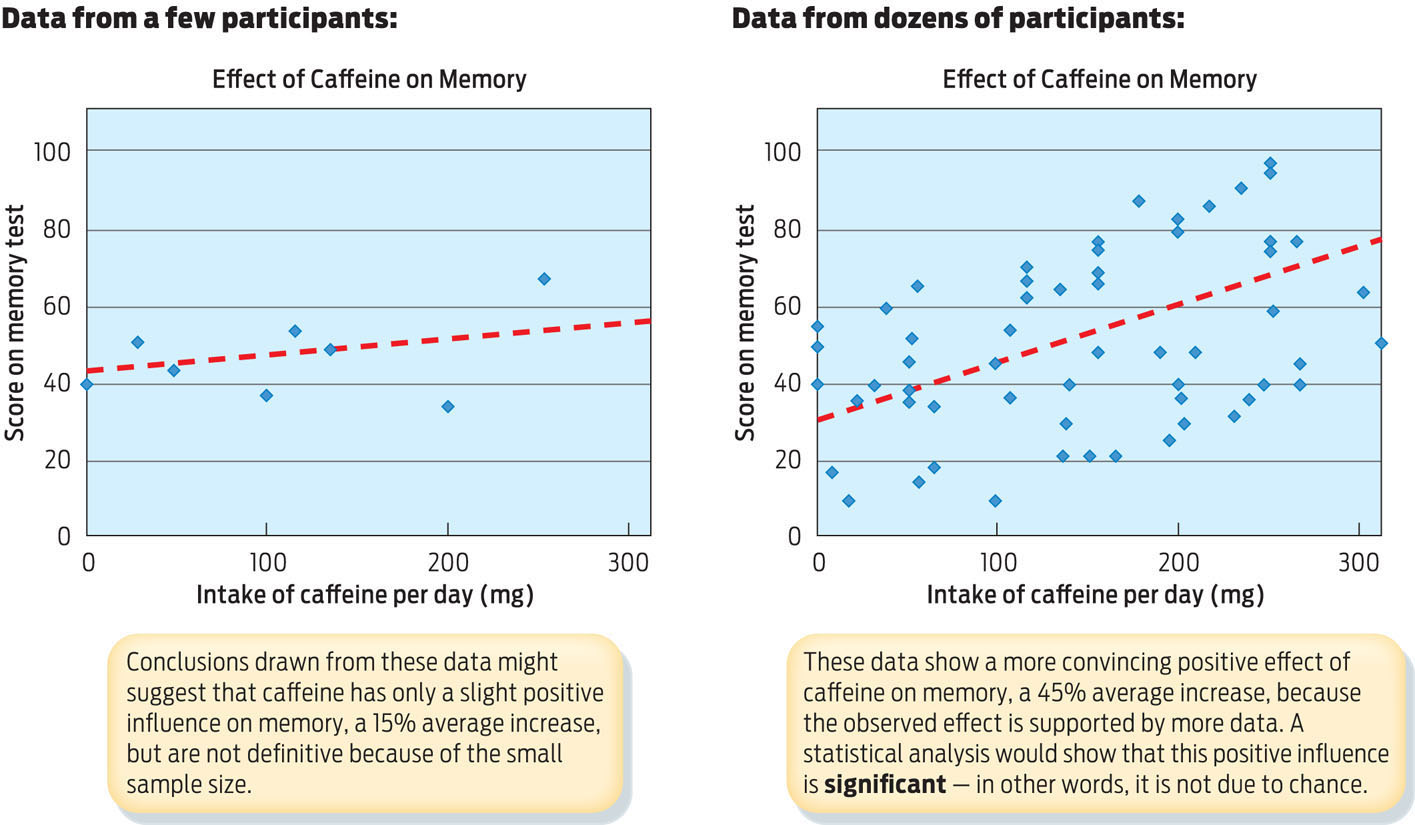

SAMPLE SIZE The number of experimental subjects or the number of times an experiment is repeated. In human studies, sample size is the number of participants.

Consider the size of Ryan’s experiment—40 people, tested on two different days. That’s not a very big study. Could the results have simply been due to chance? What if the 20 people who drank caffeinated coffee just happened to have better memory?

STATISTICAL SIGNIFICANCE A measure of confidence that the results obtained are “real” and not due to chance.

One thing that can strengthen our confidence in the results of a scientific study is sample size. Sample size is the number of individuals participating in a study, or the number of times an experiment or set of observations is repeated. The larger the sample size, the more likely the results will have statistical significance—that is, they will not be due to chance (INFOGRAPHIC 1.4).

The more data collected in an experiment, the more you can trust the conclusions.

News reports are full of statistics. On any given day, you might hear that 75% of the American public opposes a piece of legislation. Or that 15% of a group of people taking a medication experienced a certain unpleasant side effect—like nausea or suicidal thoughts—compared to, say, 8% of people taking a placebo. Are these differences significant, or important? Whenever you hear such numbers being tossed around, it’s important to keep in mind the sample size. In the case of the side effects, was this a group of 20 patients (15% of 20 patients is 3 people), or was it 2,000 (15% of 2,000 is 300)? Only with a large enough sample size can we be confident that the results of a given study are statistically significant and represent something other than chance. Moreover, it’s important to consider the population being studied. For example, do the people reporting their views on a piece of legislation represent a broad cross section of the public, or are most of them watchers of the same television network, whose views lie at one extreme? Likewise, in Ryan’s study, are the 65-year-old self-described “morning people” who regularly consume coffee representative of the wider population?

8

If you search for “caffeine and memory” on PubMed.gov (a database of medical research papers), you’ll see that the memory-enhancing properties of caffeine is a well-researched topic. Many studies have been conducted, at least some of which tend to support Ryan’s results. Generally, the more experiments that support a hypothesis, the more confident we can be that it is true.

9

Science is a way of knowing, a method of seeking answers to questions on the basis of observation and experiment.

SCIENTIFIC THEORY An explanation of the natural world that is supported by a large body of evidence and has never been disproved.

Truth in science is never final, however. What is accepted as fact today may tomorrow need to be modified or even rejected, when more evidence comes to light. Nevertheless, scientific knowledge does progress. The highest point of scientific knowledge is what’s called a scientific theory. The word “theory” in science means something very different from its colloquial meaning. In casual conversation we may say something is “just a theory,” meaning it isn’t proved. But in science, a theory is an explanation of the natural world that is supported by a large body of evidence compiled over time by numerous researchers. Far from being a fuzzy or unsubstantiated claim, a theory is a scientific explanation that has been extensively tested and has never been disproved (INFOGRAPHIC 1.5).

In everyday life, people use the word “theory” to refer to an idea that they would like to follow up. In science, a theory is a hypothesis that has never been disproved, even after many years of rigorous testing.