NO CURE FOR OBESITY

Bariatric surgery isn’t for everyone. As with any major surgery, there are risks. Although bariatric surgery is much safer today than it was 10 years ago, 1 in 200 patients still dies from the surgery. Complications after surgery include blood clots, hernias, or bowel obstructions. Patients can also end up back in the hospital to repair intestinal leaks that can lead to serious infection.

Smith has had a host of complications that have put her back in the hospital. A few months after her surgery, she felt terrible cramping in her side. Tests showed that scar tissue had formed at the site where her small intestine had been cut from her stomach. Surgery to remove the tissue revealed that part of her intestine and stomach had twisted and anchored onto this scar tissue, causing her pain. Even after the surgery, she was still having stomach pains when she ate, so doctors decided to put a feeding tube into her stomach and a catheter into a vein in her arm through which she could take nutrients directly into her bloodstream. Smith spent weeks in and out of the hospital between January and April of 2010.

Smith’s health has improved since then, but she is still at risk. Since people who have gastric bypass surgery (as opposed to gastric banding) end up with part of the small intestine bypassed, they absorb fewer of the micronutrients they eat. Patients must take vitamin supplements for the rest of their lives. There may be additional micronutrient deficiencies that scientists haven’t yet recognized; only long-term follow-up of these patients will reveal how serious a problem this is. To monitor her micronutrient levels, Smith has a blood test every 3 months.

What’s more, the surgery is not a permanent cure for obesity. Most people who have the surgery regain some weight over time. The stomach and intestines can sometimes expand to allow greater ingestion of food. And hormonal changes may occur after surgery that alter body metabolism. While scientists are still studying the hormonal mechanisms of weight gain, they do know that if people do not exercise control over their diet and lifestyle, even those who have had surgery can regain significant amounts of weight.

581

Smith’s own experience with bariatric surgery has been mixed. She still struggles with nausea every day; strong smells can cause her to vomit. She also feels pain in her left side, for which she takes medication.

Despite these complications, Smith has had not “one day of regret,” she says. On her first “surgiversary”—her surgical anniversary—she wrote a letter to her surgical team in which she said: “I have been blessed with 35 birthdays but none can compare to my surgiversary. I never imagined in a year that I would lose over 100 lbs, run a 5K the day of my surgi-versary…sit sideways in a student desk, wear a size 12 pants from a 24–26 … be able to sit comfortably in a restaurant booth, and be able to stand on a table or chair without thinking, ‘My gosh, am I going to break this?’”

By March 2011, Smith had dropped down to 146 pounds. To maintain her weight loss, she wakes up at 3:30 every morning to get to the gym to exercise, and she adheres to a strict diet that is high in protein and sparse on simple sugars like sweets. “I don’t recognize myself anymore,” Smith says.

Of her strict regimen, Smith says, “The surgery is merely a tool. If you aren’t willing to make a lifestyle change, it’s not going to work for you.”

FOR COMPARISON How Do Other Organisms Digest Food?

Humans and many other animals have what’s known as a complete digestive tract—one shaped like a tube, with two openings: a mouth and an anus. Not all organisms have such a tubelike digestive tract. In fact, many organisms have no digestive tract at all and yet are still able to obtain and process food from their environment.

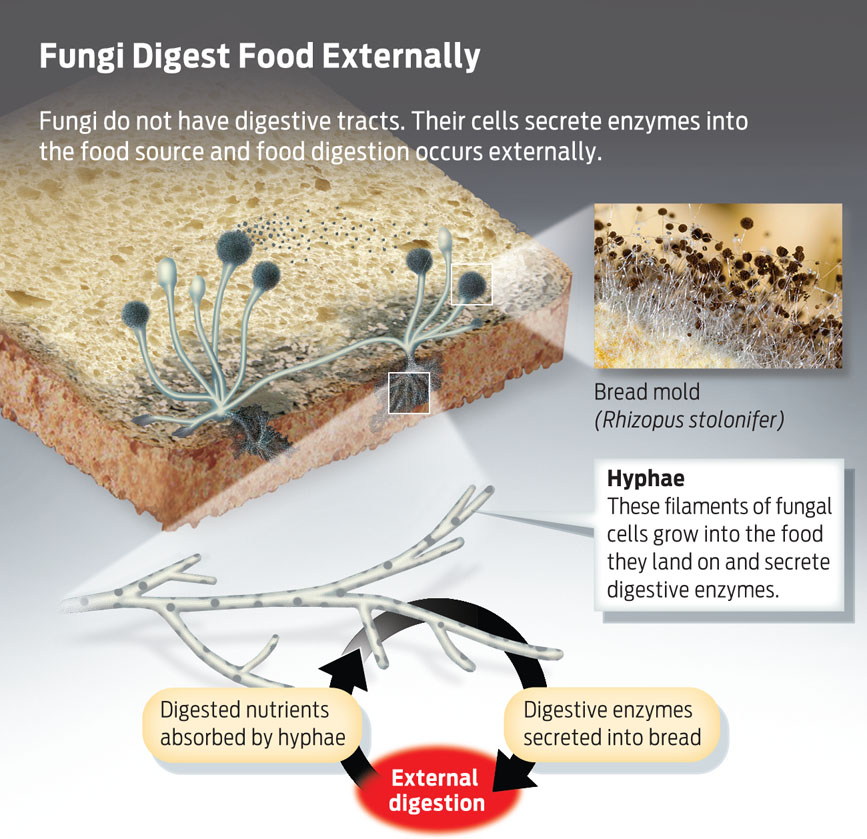

Take fungi, for example. Fungi are eukaryotic organisms. Some, such as yeasts, are unicellular, while the majority are multi-cellular. Multicellular fungi have bodies that are made up of microscopic filaments called hyphae. Their bodies do not have distinct organs or organ systems, and they do not have digestive tracts. To obtain nutrients, fungi extend hyphae into food—a piece of bread, say, or leaf litter in a forest. Individual hypha cells then release digestive enzymes directly into the food and absorb the digested nutrients directly. Since digestion occurs outside their bodies, fungi do not need a stomach or a mouth, or even a digestive tract. Rather, each cell can absorb the products of this external digestion directly.

582

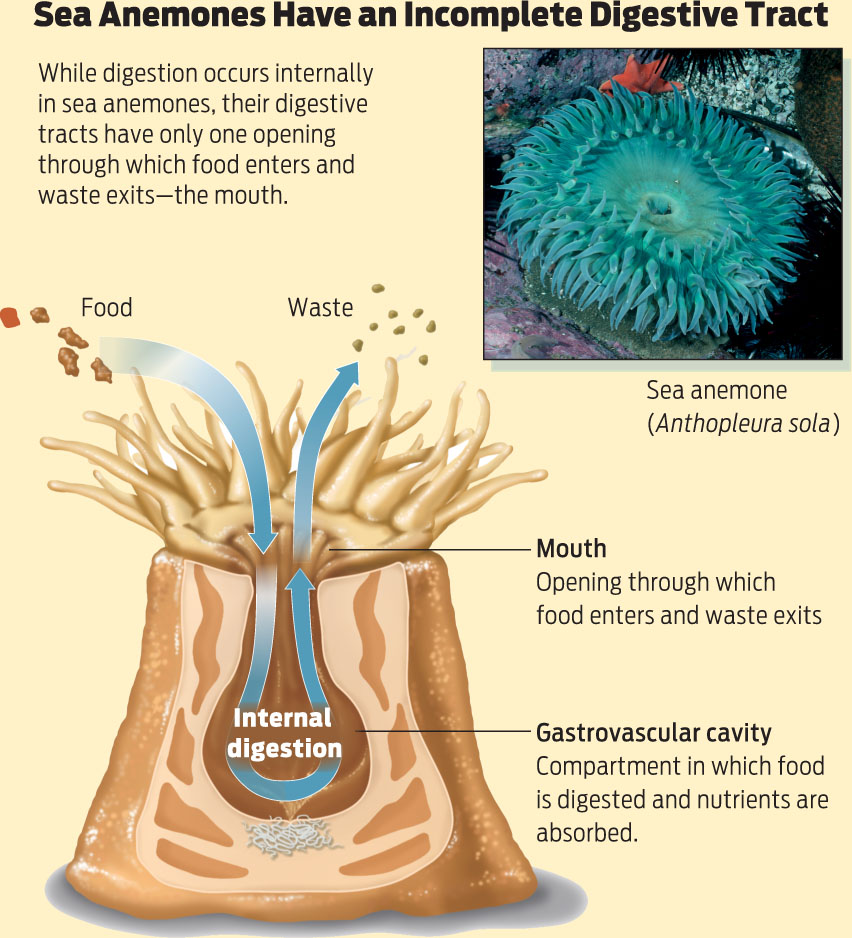

As another example, consider sea anemones, invertebrate animals that live in the oceans, attached to surfaces such as rocks. Sea anemones digest their food internally, but they don’t have a digestive tract like humans. Rather, they have a single, multifunctional digestive cavity called a gastrovascular cavity, where digestion and absorption of nutrients take place. Sea anemones capture food and shove it into this cavity using the tentacles that surround their mouths. The gastrovascular cavity has only one opening—the mouth—through which food enters and wastes exit. This is an example of an incomplete digestive tract, in contrast to our own complete digestive tract in which food flows one way from the mouth to the anus.

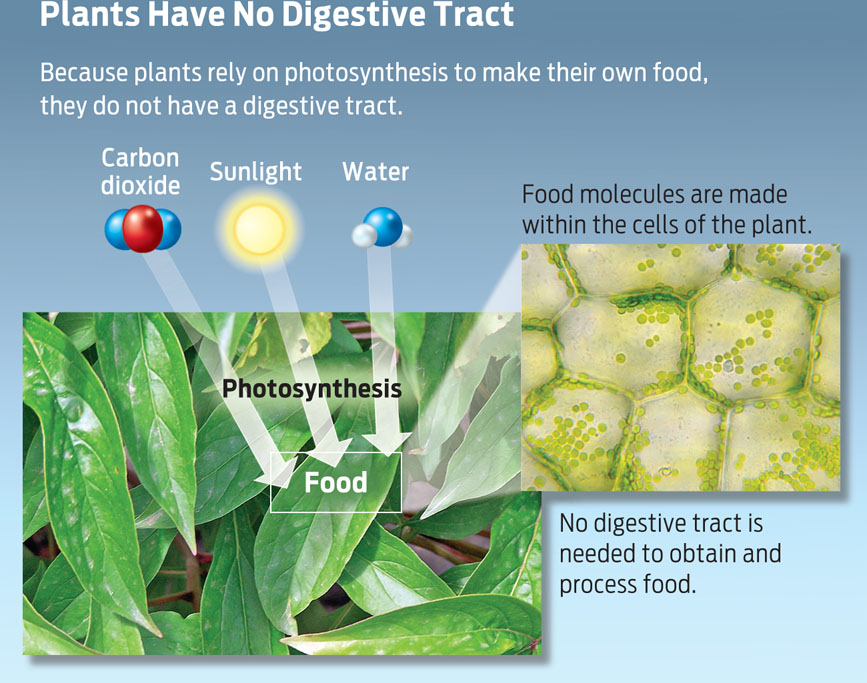

Photosynthetic organisms such as plants do not need a digestive system because they are autotrophs: they make their own food and therefore don’t need to “eat” it (see Chapter 5). Instead, they take up carbon dioxide and use water and the energy of sunlight to convert the atmospheric carbon dioxide to carbohydrates in the plant body.

583