Plant Hormones

Can plants see?

Can plants see?

PHOTOTROPISM The growth of the stem of a plant toward light.

ANSWER: Observe an old building and you’ll likely see ivy scaling up its walls. Keep houseplants next to a window and you’ll find them bending toward the sunlight. How does a plant know where it’s going? While plants don’t have eyes and therefore cannot see, they are quite adept at sensing and responding to their environment, which they do through various kinds of tropism (from the Greek tropos, meaning “turn”).

AUXIN A plant hormone that causes elongation of cells as one of its effects.

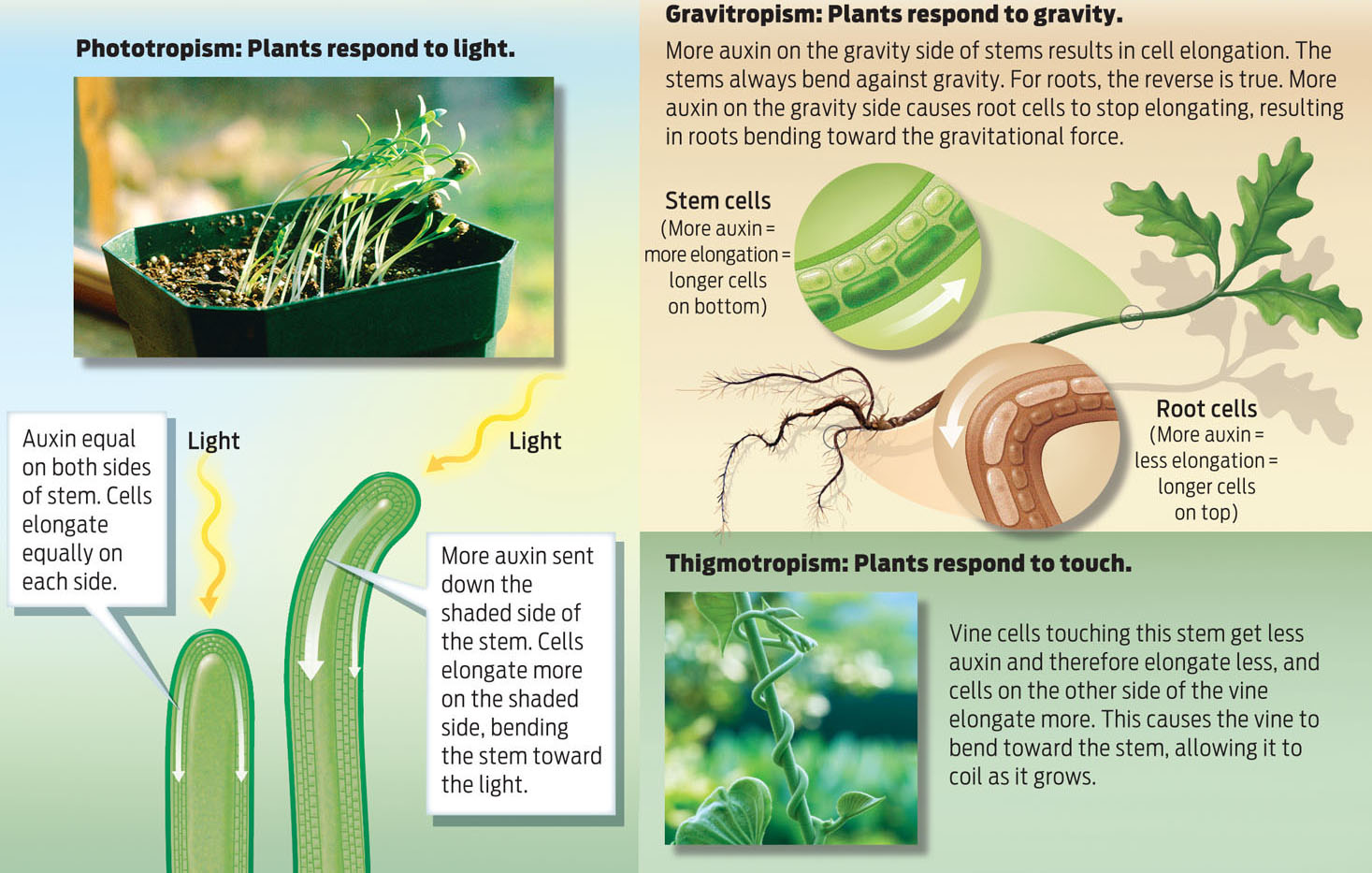

The growth of a plant shoot toward light is called phototropism. This is how leaves get the sunlight they need for photosynthesis, and it’s why ivy climbs up walls and houseplants lean into the window. Shoots grow toward the light because of auxin, a plant hormone that promotes cell elongation as one of its effects. When light hits one side of a plant shoot, auxin moves to the shaded side, creating a gradient of the hormone in the stem. The side receiving the most direct sunlight contains the least auxin, while the shaded side contains the most. Auxin promotes elongation of cells on the shady side of the stem. This causes the shaded side to elongate faster than the sunny side, pushing the stem toward the sun. The whole stem doesn’t sense light and produce auxin, though—just the tip of the stem. Cover the tip of a young plant and it won’t turn toward the light, but will instead grow straight up because, in the absence of sunlight, auxin is not differentially localized to one side of the stem.

GRAVITROPISM The growth of plants in response to gravity. Roots grow downward, with gravity; shoots grow upward, against gravity.

Other mechanisms help a plant sense where it is and orient itself in space. Gravitropism is the growth of plants in response to gravity—roots grow downward, with the force of gravity, and shoots grow upward, against it. Auxin is again the main player in this mechanism. When a plant is placed on its side, more auxin is sent to the down side of the stem, in the direction of gravity. This causes the cells on the down side to elongate more. Stems begin to curve away from gravity. Root cells, however, respond the opposite way to auxin: more auxin on the gravity side of roots inhibits root cell elongation on the down side, so roots bend toward gravity. Gravitropism allows a planted seed to send its shoots toward the light and its roots toward the soil.

THIGMOTROPISM The response of plants to touch and wind.

730

A plant’s sense of touch is called thigmotropism; it’s how vines sense their way around poles or trellises and carnivorous plants sense their prey. Touch-sensitive growth is also controlled by auxin. Vine cells touching a pole, for example, get less auxin and consequently elongate less, while cells on the other side elongate more. The result is another kind of lopsided growth in the shoot, which eventually causes the vine to coil around whatever it’s touching. A plant’s sense of touch can be exquisitely sensitive—more sensitive than a human’s. A human can detect the presence of a thread weighing 0.002 mg laid across the arm. By contrast, the feeding tentacle of the insectivorous sundew plant can sense a thread of less than half that weight. The legs of a single gnat are enough to trigger the tentacle into swift action (INFOGRAPHIC 32.8).

Plants can respond to a variety of stimuli, including light, touch, and gravity. Many of these responses are mediated by a plant hormone called auxin. Unequal distribution of auxin leads to a corresponding unequal pattern of cell elongation in stems and roots, and thus growth in a particular direction.