Plant Defenses

Why are some plants poisonous?

Why are some plants poisonous?

ANSWER: From juicy peaches and succulent strawberries to zesty basil and peppery arugula, many plants are incontestably delicious. Humans aren’t the only ones who think so. Many herbivores such as insects, birds, rodents, and other small mammals find plant parts tasty and irresistible. This is both helpful and hurtful to a plant. On the one hand, plants rely on animals to eat their fruits and disperse their seeds. On the other hand, plants must ensure that only noncrucial parts of the plants are eaten by other organisms. Eating a plant’s fruit is one thing; eating all of its leaves is quite another.

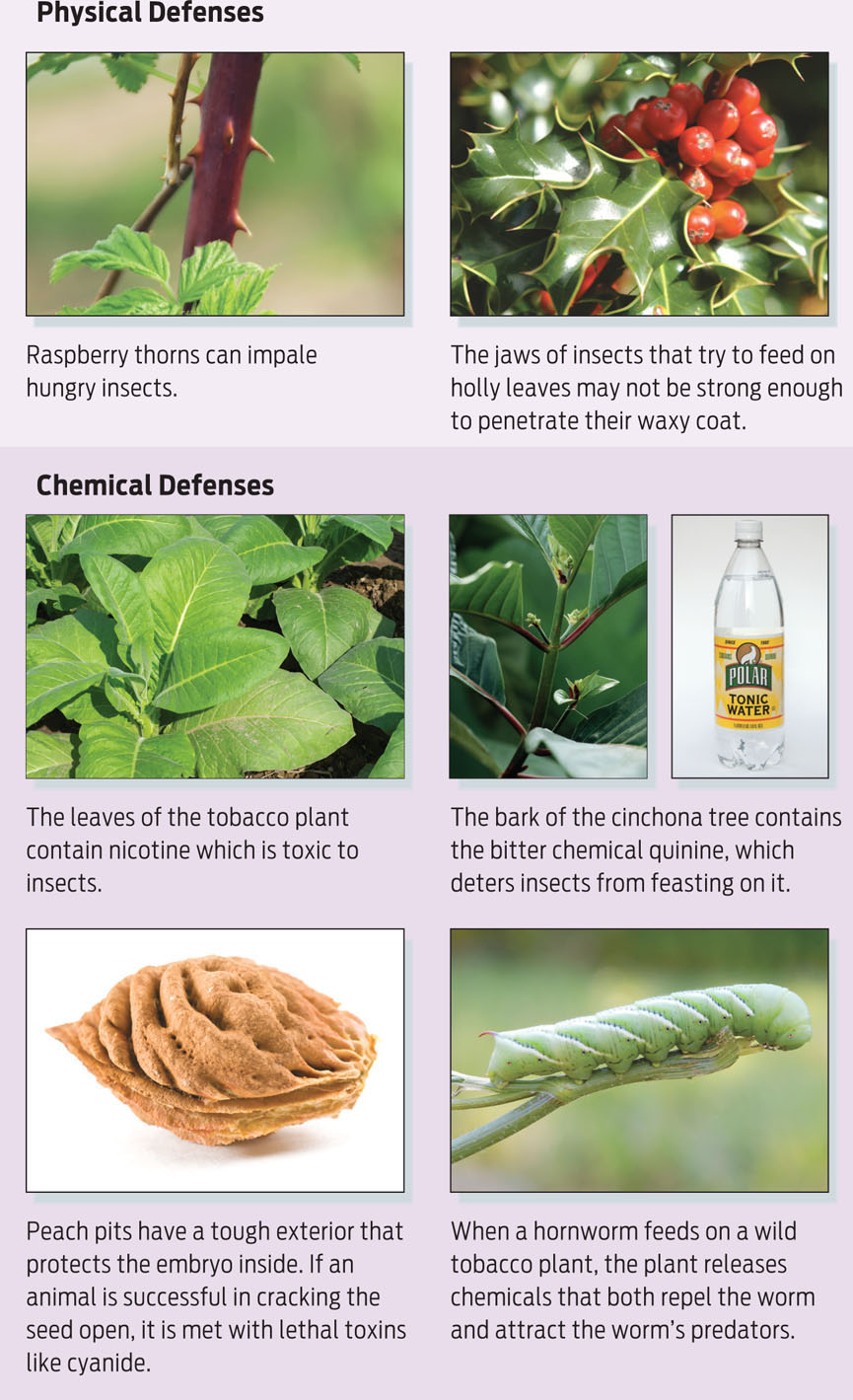

Plants have evolved many defenses to protect their important parts from an herbivore’s chomping. Some defenses are mechanical: the stems of a raspberry plant are covered in prickly spines to prevent unwanted chewing; holly leaves are waxy and difficult for insect jaws to grasp. Other defenses are chemical: leaves of the tobacco plant produce nicotine, which is toxic to insects; the bark of the South American evergreen cinchona tree produces quinine, an extremely bitter substance that many animals find distasteful (except certain humans, who use it in their gin and tonics). Such antiherbivory chemicals are a highly effective way to deter pests from eating a plant’s leaves.

While a plant’s fruits are often tasty and meant to be digested, seeds generally are not. The seed contains a new plant, and therefore it must be protected. Many seeds are encased within an indigestible shell that prevents them from being destroyed by an animal’s stomach juices. The unlucky animal that succeeds in breaking open the shell and eating the seed is in for an unwelcome surprise. Seeds are sources of some of the most potent poisons on Earth, including ricin, cyanide, and strychnine. Ricin, found in castor beans, can be lethal to animals in quantities as little as two beans. Cyanide, which is found in small doses in the seeds of peaches, apricots, and apples, kills by interrupting cellular respiration in mitochondria; unable to make ample amounts of the short-term energy-storage molecule ATP, nerve and muscle tissues quickly shut down.

733

Plants also use chemicals to combat other plants. Blue gum eucalyptus trees (Eucalyptus globulus), for example, secrete a sticky gumlike substance that acts as a deterrent to the germination and growth of noneucalyptus plants in the nearby vicinity.

Perhaps the most interesting method of deterrence that plants use is a kind of unwitting alliance. Some plants, such as wild tobacco, emit potent vapors when they are eaten by insect pests. The vapors, in turn, attract natural predators of the insects, which are thus enlisted in the plant’s defense. This “enemy of my enemy” approach is an example of mutualism (see Chapter 22) (INFOGRAPHIC 32.11).

Individual plants can even communicate with other individuals of their species and unite against a common enemy. At the first sign of grazing by a hungry giraffe or antelope, for example, African acacia trees release a bad-tasting poison into their leaves. At the same time, they release a gaseous chemical—the versatile hormone ethylene—which drifts out of the stomata of their leaves. Other acacias in a 50-yard radius detect the gas and are prompted to start releasing poison in their leaves, too.

Although antiherbivory chemicals complicate an herbivore’s life, they are often quite useful to humans. Some of our most important medicines are extracts of plant chemical defenses, including aspirin, morphine, digitalis, and the anticancer drug Taxol, which was originally obtained from the bark of the Pacific yew tree (see Chapter 8).

734