66

67

DRIVING QUESTIONS

- What does endosymbiosis say about the origin of organelles such as mitochondria and chloroplasts?

- What evidence supports the proposed origin of organelles such as mitochondria and chloroplasts?

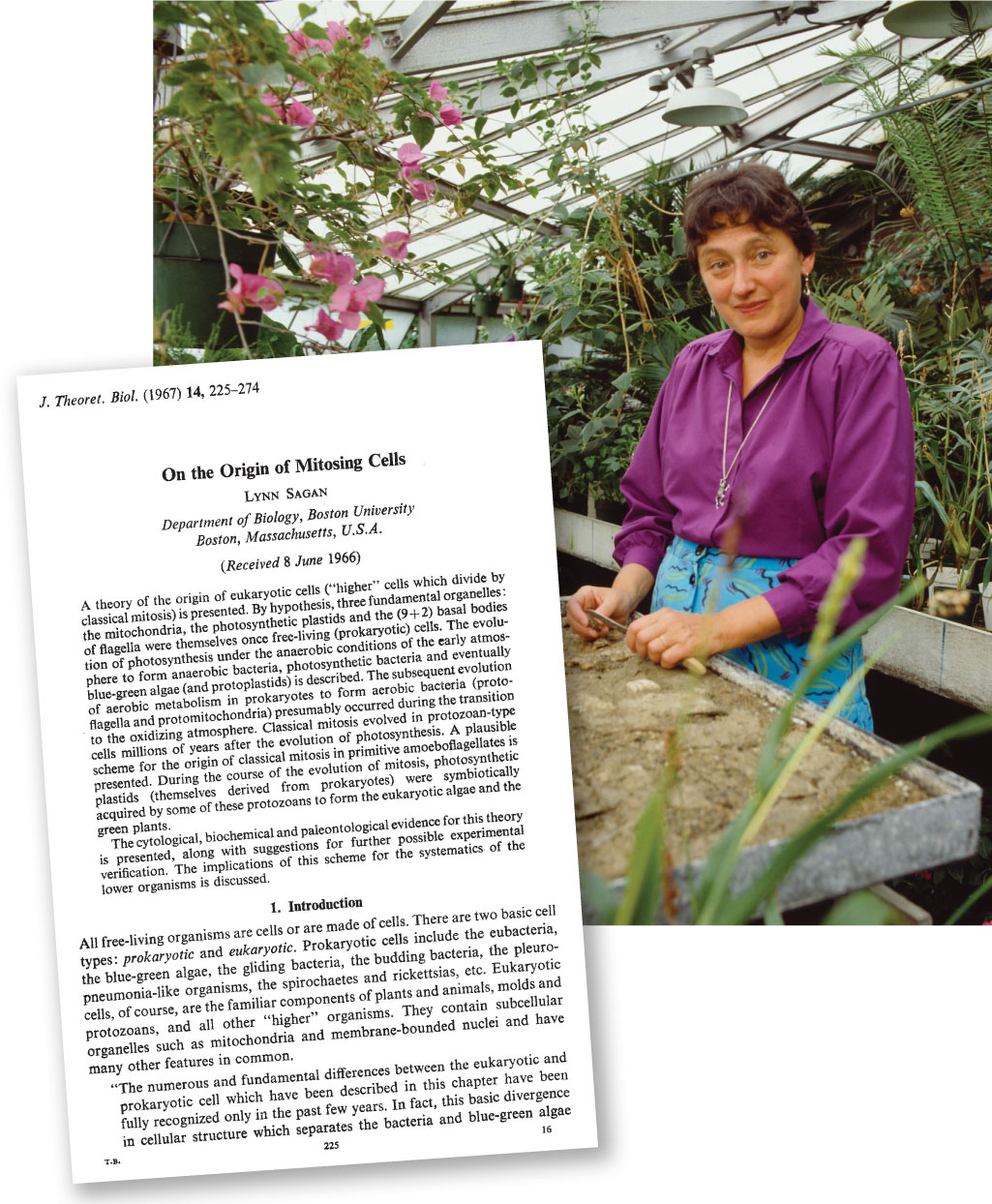

YNN MARGULIS NEVER MET A MICROBE SHE DIDN’T LIKE. From the time she first peered through a microscope as a teenager at the University of Chicago and witnessed the vast microcosm of unicellular organisms swimming in a drop of pond water, she was hooked. Other biologists were impressed by the adaptations of plants and animals, but Margulis was smitten with the world of microscopic life. Long before there were animals on the planet, she pointed out, there were microbes, and if it weren’t for them, we humans wouldn’t be here.

YNN MARGULIS NEVER MET A MICROBE SHE DIDN’T LIKE. From the time she first peered through a microscope as a teenager at the University of Chicago and witnessed the vast microcosm of unicellular organisms swimming in a drop of pond water, she was hooked. Other biologists were impressed by the adaptations of plants and animals, but Margulis was smitten with the world of microscopic life. Long before there were animals on the planet, she pointed out, there were microbes, and if it weren’t for them, we humans wouldn’t be here.

“Life on Earth is such a good story you can’t afford to miss the beginning,” Margulis said in an interview with the University of Wisconsin alumni magazine. “Do historians begin their study of civilization with the founding of Los Angeles? This is what studying natural history is like if we ignore the microcosm.”

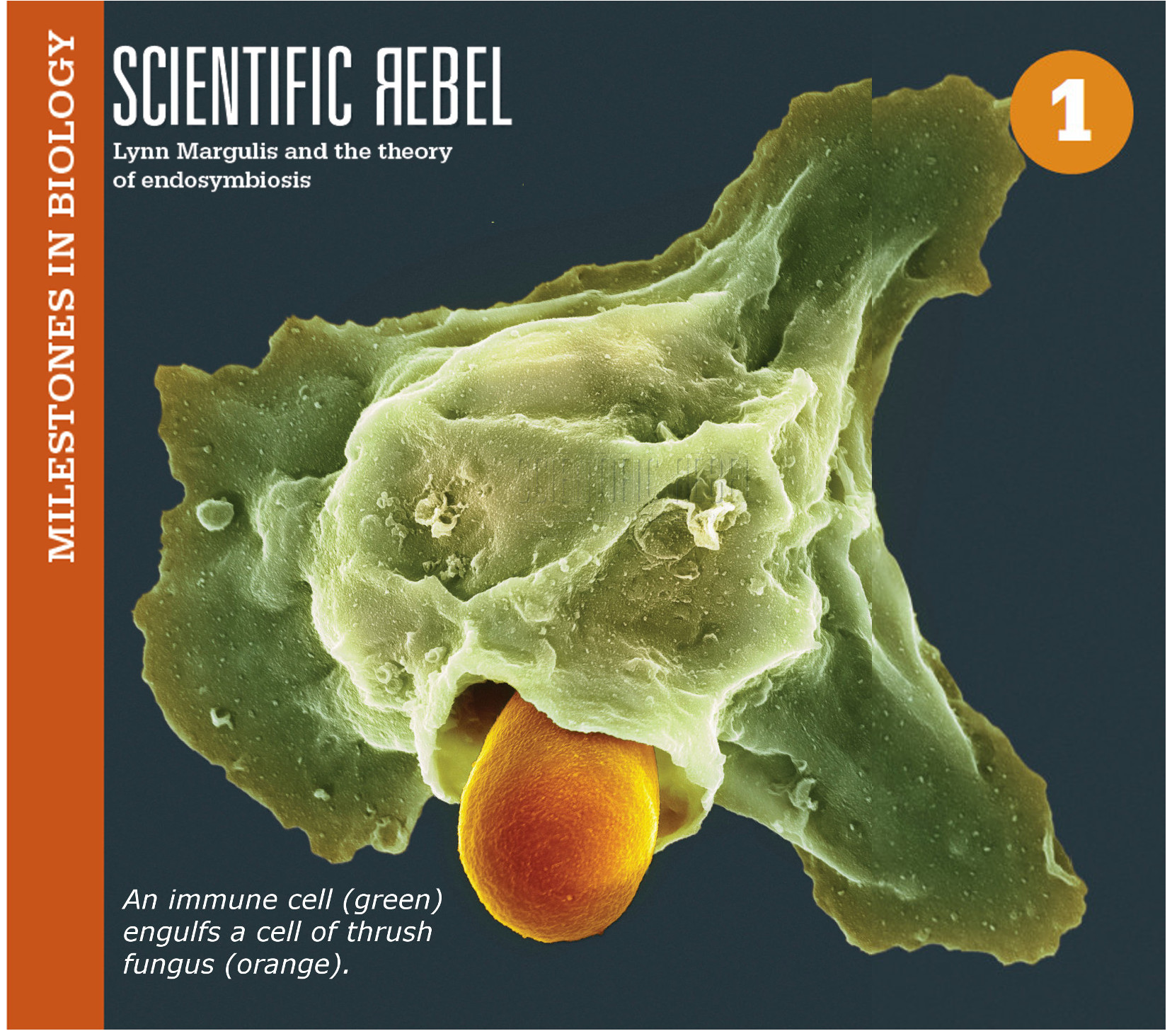

In 1966, when she was 28, Margulis used her knowledge of the microcosm to propose a radical hypothesis about how cells had come to be. What distinguishes eukaryotic cells from prokaryotic cells, Margulis knew, was the presence in eukaryotic cells of internal membrane-bound organelles (see Chapter 3). Margulis proposed that eukaryotic cells, with their internal organelles, had formed when one prokaryotic cell engulfed another–essentially eating it for lunch. Instead of being digested, the ingested cell survived and took up residence in its new host. Eventually, the two cells formed a mutually beneficial relationship, and the result was a complex eukaryotic cell. Margulis called her idea endosymbiosis (from the Greek “endo” meaning “within,” and “symbiosis” meaning “living together”).

68

Many scientists dismissed the idea outright as a crackpot notion. The paper she wrote proposing the idea, which she titled “On the Origin of Mitosing Cells,” was rejected by about 15 scientific journals before finally being accepted by the Journal of Theoretical Biology, in 1967. But an interesting thing happened after it was published: people couldn’t stop talking about it.

Life on Earth is such a good story you can’t afford to miss the beginning.

–LYNN MARGULIS