Legally mandated protection can aid in species conservation

Whether African elephants represent one species or two has huge implications for conservation biology. The Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES)—an international treaty that regulates global trade of selected species—banned the trade of African elephant ivory in 1990. Since then, various governing bodies across Africa and Asia have been lobbying to ease those restrictions. So far, they have had little success, but with two distinct species, Blake says, they may finally have their way. “The forest elephant has been gravely imperiled by poaching,” he says. “But the savanna elephant, by many accounts, is doing just fine. So, if they are two different species, CITES could now open the trade in savanna elephants.” Demand would then rise, he says. And ivory prices would, too. “Rising demand and rising prices will make it even more profitable for black marketers to operate, and ultimately, the forest elephants will suffer even greater decimation.”

Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES)

An international treaty that regulates the global trade of selected species.

There are also international treaties that protect species and ecosystems around the world. The 1992 Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) attempts to reach even further than CITES, supporting conservation and sustainable use of all biological diversity, not just endangered species. But because CBD is less concrete than CITES—it does not outline any specific targets or provide a mechanism to reach its goals, leaving it up to each signatory to determine how best to proceed—it has been less successful.

Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD)

An international treaty that promotes sustainable use of ecosystems and biodiversity.

National laws also protect endangered species. The two main laws in the United States are the Marine Mammal Protection Act and the better-known Endangered Species Act (ESA). Passed in 1973, the ESA mandates that listed species—those that have been officially declared threatened or endangered—be protected through a range of federally funded and scientifically proven strategies. Those strategies include the conservation of natural habitats as well as the breeding, relocation, and/or reintroduction of captive animals into the wild. The law has been controversial since its passage. It has certainly succeeded in bringing back several iconic species from the brink of extinction—the bald eagle and the American alligator, to name just two. But its effectiveness has also been perpetually hampered by a variety of constraints— including landowner disputes and what critics describe as colossal funding shortfalls. TABLE 13.1

Endangered Species Act (ESA)

The primary federal law that protects biodiversity in the United States.

LEGAL PROTECTION FOR SPECIES

U.S. environmental laws like the ESA are considered “citizen laws”—citizens or citizen groups (like nonprofit organizations) can sue the federal government to enforce the law if they feel it is not doing so. The Canadian version of this law (Species at Risk Act) does not have this provision. Which law do you think is stronger (i.e., more successful at protecting species)?

Answers will vary but should be supported. In general, the ESA is considered the stronger law due to the ability of citizens or citizen groups (like nonprofit organizations) to litigate for its enforcement.

Of course, CITES has troubles of its own—especially where the African forest elephant is concerned. Member nations meet every few years to review the status of various species and to modify their regulation, if necessary—a process that critics say is as fraught as the ESA’s with political maneuvering, budget woes, and other practical difficulties.

250

KEY CONCEPT 13.7

Legal protection for threatened species includes national laws and international treaties as well as the establishment of protected areas.

At a 2010 conference, Zambia and Tanzania petitioned CITES for permission to sell their stockpiled ivory—that which had come from elephants that died naturally or that were killed before the ban was implemented. The ivory was just sitting there, the countries’ representatives argued. The elephants were already dead, and the countries themselves could really use the money.

In the past, several African nations had, with permission from CITES, auctioned off their confiscated and stockpiled ivory (some of which had come from culled animals—those killed off deliberately when herds exceed park capacity). Selling this ivory was supposed to help elephant conservation efforts by reducing the market for illegally killed animals (and by increasing funds for conservation initiatives). But in the end, poaching only increased.

Opponents to the Zambian and Tanzanian request argued that such allowances would only bolster the illegal trade, which they said was already rampant in both of the petitioning nations. Zambia and Tanzania denied the charge, insisting that poaching had been all but eliminated within their borders. The conference grew heated, and the two sides quickly reached an impasse.

And then Wasser presented his data: DNA analysis showing that much of the ivory seized that year—more than 60% of that which had been smuggled to ports in China and Thailand and New York—did indeed come from Tanzania and Zambia.

The petition was quashed. Since that time several countries, including China and the United States, have destroyed many tons of ivory stockpiles (by crushing and/or burning), hoping to send a clear message to potential poachers or consumers that ivory trafficking will not be tolerated.

251

Protected areas provide another legal avenue for conservation. Protected areas are clearly defined geographic spaces on land or at sea that are recognized, dedicated, and managed to achieve long-term conservation of nature. Every nation in the world has protected areas. They include a range of designations. National parks are set aside primarily for human recreation. Wildlife refuges and wilderness areas are generally open to visitors, as well as to hunting and fishing, but are not commercially developed (i.e., they have no restaurants, hotels, or other human accommodations). Nature preserves (also called nature or game reserves) are closed to hunting and fishing; their main goal is to protect wildlife.

protected areas

Geographic spaces on land or at sea that are recognized, dedicated, and managed to achieve long-term conservation of nature.

Evidence is mounting that protected areas are helping. For example, after a serious coral bleaching event, Kanton Island reef in the South Pacific was designated a marine protected area. Its remarkable recovery (in less than a decade) is attributed to the protection of the entire ecological community (see LaunchPad Chapter 29). Likewise, the African white rhinoceros, a species once believed to be extinct, is thriving in protected areas; its conservation status has been upgraded to vulnerable. INFOGRAPHIC 13.6

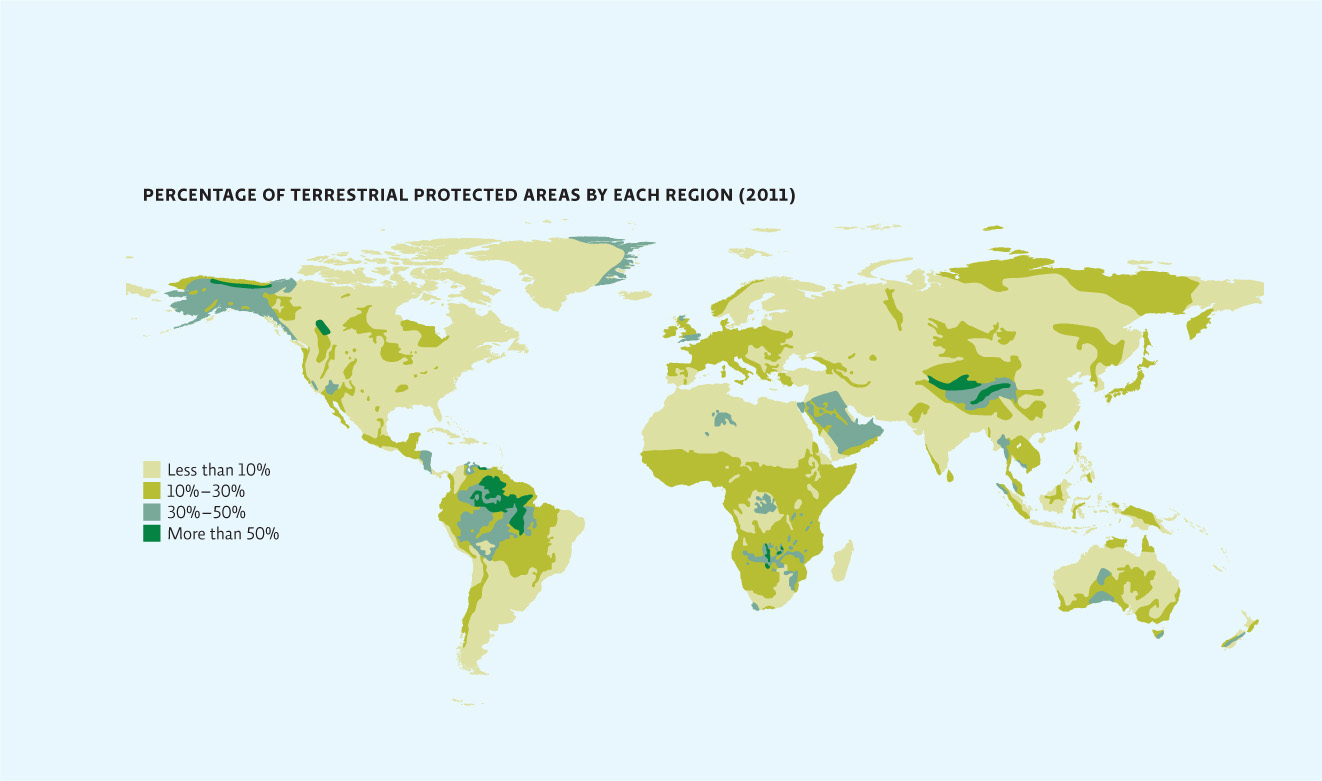

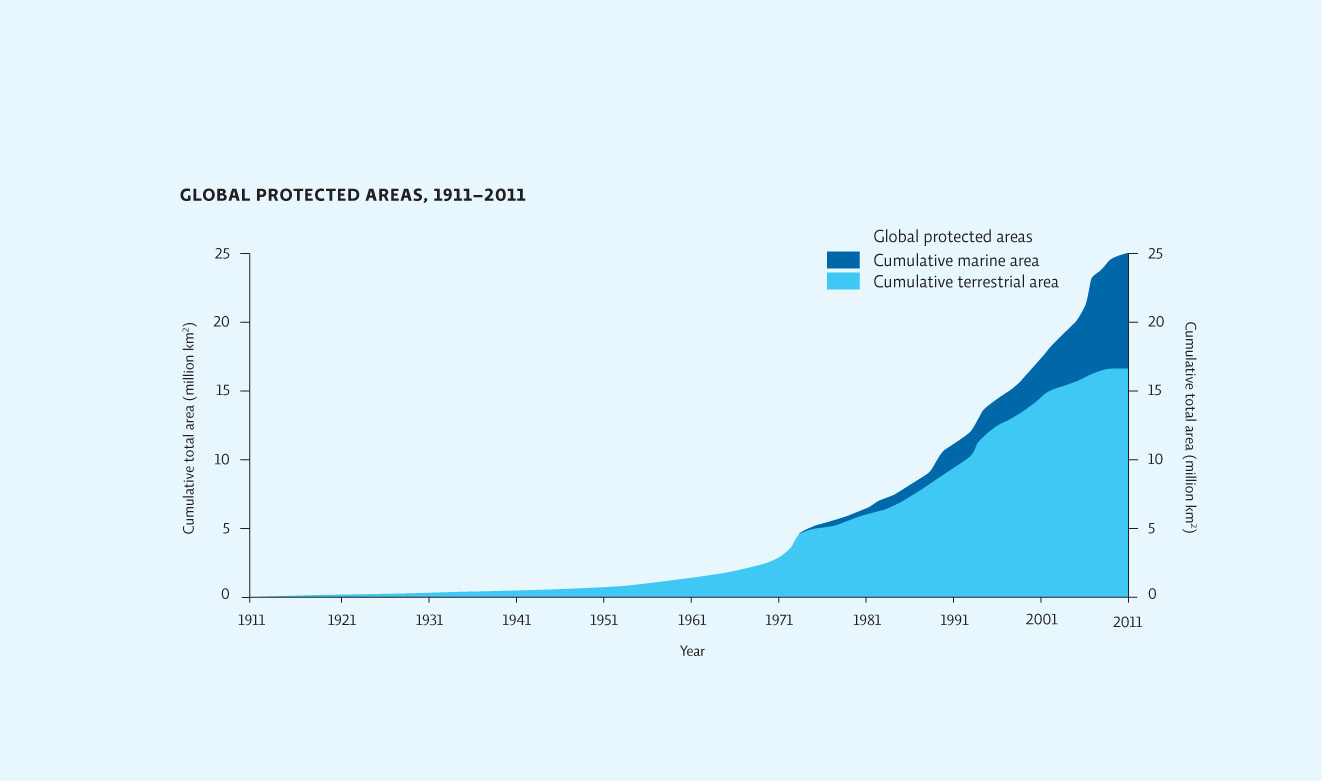

GLOBAL PROTECTED AREAS

Protected areas come in all shapes and sizes and vary according to what level of protection the area receives (e.g., a wildlife refuge that allows hunting of some species versus a nature preserve that does not allow any hunting). About 13% of land on Earth has some protected status (only 1.6% of the oceans are protected; see LaunchPad Chapters 29 and 31 for more on marine protected areas).

Which area of the United States has the highest percentage of protected area? Why do you suppose this area has the most protection?

Alaska has the highest percentage of area that is protected (30-50%). This may be because much of Alaska is wilderness with high conservation value (many important or threatened species). It may also be that much of Alaska is sparsely settled so the residents or government was willing to set aside land for protection.

Starting with 1961–1971, estimate how many million square kilometers were added in each 10-year period. In which decade was the most land area designated as protected?

From 1961-1971, about 1.5 million km2 were added; from 1971-1981, about 3 million km2 were added; from 1981-1991, about 4 million km2 were added; from 1991-2001, about 5 million km2 were added; from 2001-2011 about 3 million km2 were added. Therefore, 1991-2001 saw the greatest amount of land designated as protected.

252

As with legal safeguards like the ESA and CITES, protected areas have limits. According to the WCS, elephant poaching is lower—and overall elephant populations are dramatically higher—in national parks and game reserves, especially in the eastern and southern regions of Africa, where the savanna elephant is thriving. But most experts agree that protected areas are not enough to save much of anything in the long run. The physical condition of such reserves, and the type and amount of species that can survive inside them, are changing, says Evans. “Whether it’s because of global warming, or road building, or other factors, we’ve already got huge percentages of elephants living outside these protected areas. And what happens then? When those protected areas become places that they can’t live? We haven’t yet thought about what we are going to do when that happens.”

For its part, the WCS is urging private logging and mining companies to curb illegal hunting in their concessions, especially when those concessions are near protected areas. “We need to start moving away from that idea of distinct areas, towards a place of coexistence,” Evans says. And that will never happen without the support of local communities.