Reclaiming a closed mining site helps repair the area but can never re-create the original ecosystem.

In some ways, closed mines—those where all the coal has been harvested—look even more alien than do active sites like Hobet 21. Instead of the natural sweep of rolling hills, staircase-shaped mounds covered with what looks like lime-green spray paint join one mountain to the next. Atop some of them, gangly young conifers, evenly spaced, strain toward the Sun. The spray paint is really hydroseed, and most of the gangly trees are loblolly pine, a non-native hybrid that foresters are trying to grow in the region.

Such efforts represent the coal industry’s attempt to honor the U.S. Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act, which in 1977 mandated that areas that have been surface mined for coal be “reclaimed” once the mine closes. Reclamation requires that the area be returned to a state close to its pre-mining condition.

reclamation

The process of restoring a damaged natural area to a less damaged state.

KEY CONCEPT 18.8

Surface coal mines must undergo reclamation once they are closed; this reduces the environmental damage of mining but does not eliminate it.

At some surface mines, at least, reclamation is straightforward (albeit labor-intensive) work: If the mined area was originally fairly flat, the reclamation process includes filling the site with the stockpiled overburden and contouring the site to match the surrounding land. This relaid rock is then covered with topsoil saved from the original dig. Sometimes, alkaline material such as limestone powder is sprinkled overtop to neutralize acids that have leached into the soil. Vegetation, usually grass, is then planted, leaving other local vegetation to move in on its own. According to the Mineral Information Institute, more than 1 million hectares (2.5 million acres) of coal-mined area have been successfully reclaimed using this strategy.

356

But reclamation has always been a controversial idea. For one thing, the Appalachian forests were created over eons. In fact, in some ways, they were born of the same calamity that laid the coal beneath the mountains. As the supercontinent drifted, carrying the Appalachian range well north of the equator, a temperate hardwood forest replaced the swamps and grew over time into one of the most biologically diverse ecosystems on the planet. In some areas, a single mountainside may host more tree species than can be found in all of Europe, not to mention songbirds, snails, and salamanders that exist nowhere else on Earth. No amount of human restoration can re-create the mountain habitat or bring back the species diversity and nuanced ecosystem relationships born of millions of years of evolution.

From a practical point of view, rebuilding a mountain is considerably more difficult than filling in a strip mine where the original land was relatively flat. Critics say that so far, there’s no evidence that a site as expansive and as thoroughly destroyed as Hobet 21 could ever be truly reclaimed. In one survey, Rutgers ecologist Steven Handel found that trees from neighboring remnant forests did not readily move in to recolonize mountaintop removal sites, largely because of problems with the soil: At some mines, there was simply not enough of it; at others, it has not been packed densely enough for trees to take root. Those problems have technical solutions, Handel says but so far, the seemingly simple act of changing reclamation protocols has been stymied by politics.

And trees are just one facet of reclamation. What about all those streams that were buried? The 1973 Clean Water Act prohibits the discharge of materials that bury a stream or, if unavoidable, requires mitigation efforts that return the stream close enough to its original state such that the overall impact on the stream ecosystem is “nonsignificant.” Federal regulations also require that damaged streams be restored. Industry reps argue that they are indeed working to rebuild streams: Once the overburden has been reshaped and smoothed over, they dig drainage ditches and line them with stones in a way that resembles a stream or river. But so far, research shows—and most ecologists agree—that such channels don’t perform the ecological functions of a stream. “They may look like streams,” says ecologist Margaret Palmer from the University of Maryland. “But form is not function. The channels don’t hold water on the same seasonal cycle, or support the same aquatic life, or process contaminants out of the water—all things a natural stream does.” INFOGRAPHIC 18.8

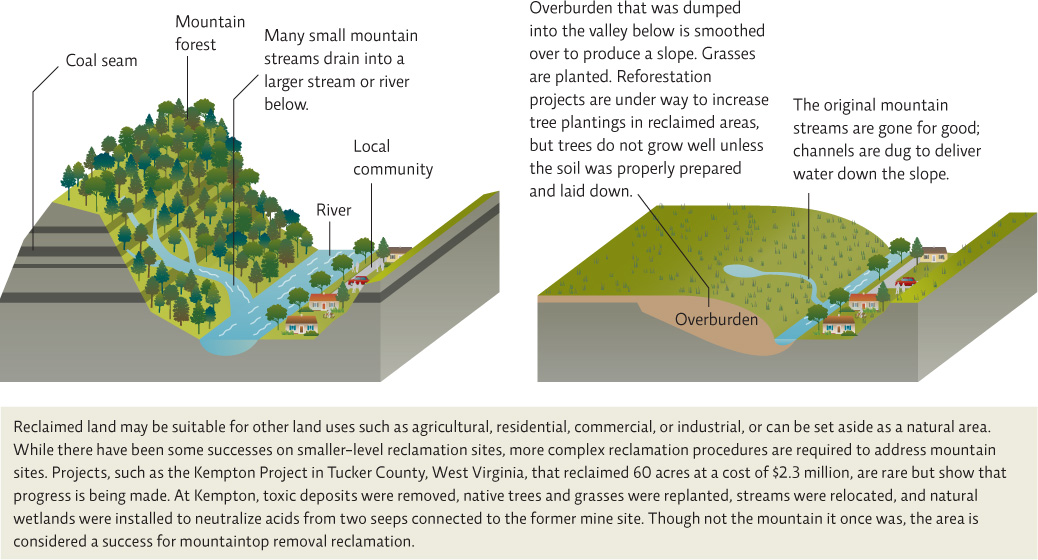

MINE SITE RECLAMATION

U.S. federal law requires that after a surface coal mine ceases operations, the land must be restored to close to its original state. However, mining sites never truly or fully recover. After the coal is removed, the area is recontoured to produce a slope, and grasses are planted. To replace the mountain streams that were buried by the mining removal process, new channels are constructed to accommodate water flow— but these channels do not support the diverse biological communities that once existed. No matter how much care goes into reclamation, the area will not support a mountain forest community like it once did. However, if done well, a new ecological community may develop.

If you lived near an areas where mountaintop removal mining was being done, would you be satisfied with the reclamation process ‘and final product? What are the advantages and disadvantages of this type of reclamation?

Answer: Answers will vary regarding satisfaction. Advantages include having flatter land that can be used for other purposes such as industry or recreations (many very mountainous areas have little industry do to the lack of suitable space to build industrial sites.) Disadvantages include the loss of cultural and community ties to the original mountain and stream habitat, loss of tourism, and potential that the area may still be contaminated.

357

In Appalachia, the arguments over when and where and how to mine for coal are quickly boiling down to a single intractable question: Once it’s all gone, how will we clean up the mess we’ve made? For a story that has played out over geologic time, the question is more immediate than one might think. In West Virginia, coal reserves are expected to last another 50 years, at best. That means no matter what regulations the government imposes, or what methods the coal companies resort to, the day of reckoning will soon be upon us.

Select References:

Ahern, M., et al. (2011). The association between mountaintop mining and birth defects among live births in central Appalachia, 1996—2003. Environmental Research, 111(6): 838—846.

Ahern, M., & M. Hendryx. (2012). Cancer mortality rates in Appalachian mountaintop coal mining areas. Journal of Environmental and Occupational Science, 1(2): 63—70.

Bernhardt, E. S., & M. A. Palmer. (2011). The environmental costs of mountaintop mining valley fill operations for aquatic ecosystems of the central Appalachians. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1223(1): 39—57.

Epstein, P.R., et al. (2011). Full cost accounting for the life cycle of coal. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences: Ecological Economics Review, 1219(1): 73—98.

Hendryx, M., & Ahern, M. (2008). Relations between health indicators and residential proximity to coal mining in West Virginia. American Journal of Public Health, 98(4): 669—671.

Inman, M. (2013). The true cost of fossil fuels. Scientific American, 308(4): 58—61.

Pond, G., et al. (2008). Downstream effects of mountaintop coal mining: Comparing biological conditions using family- and genus-level macroinvertebrate bioassessment tools. Journal of the North American Benthological Society, 27: 717—737.

United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). (2013). Global Mercury Assessment 2013: Sources, Emissions, Releases and Environmental Transport. Geneva, Switzerland: UNEP Chemicals Branch.

U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. (2005). Final Programmatic Environmental Impact Statement on Mountaintop Mining/Valley Fills in Appalachia. Philadelphia, PA: EPA.

Weakland, C. A., & P. B. Wood. (2005). Cerulean warbler (Dendroica cerulea) microhabitat and landscape-level habitat characteristics in southern West Virginia. The Auk, 122(2): 497—508.

PERSONAL CHOICES THAT HELP

Although coal is one of our most abundant fossil fuels, its drawbacks are significant. They include CO2 emissions, the release of air pollutants that cause environmental problems such as acid rain, health problems such as asthma and bronchitis, and massive environmental damage from the mining process. One way to minimize the impact of coal is to reduce consumption of electricity.

Individual Steps

Always conserve energy at home and in your workplace.

Turn off or unplug electronics when not in use.

Put outside lights on timers or motion detectors so that they come on only when needed.

Dry clothes outdoors in the sunshine.

Turn the thermostat up or down a couple of degrees in summer and winter to save energy and money.

Group Action

Organize a movie screening of Coal Country or Kilowatt Ours, which present issues related to coal mining and mountaintop removal from many perspectives.

Policy Change

The Appalachian Regional Reforestation Initiative is a great example of how groups, sometimes with very different objectives, can work toward a common goal. Go to http://arri.osmre.gov to see how this coalition of the coal industry, citizens, and government agencies are working to restore forest habitat on lands used for coal mining. Visit http://beyondcoal.org to find out about events in your state and for the opportunity to weigh in on the decommissioning of outdated coal power plants and the building of new ones in the United States.

358