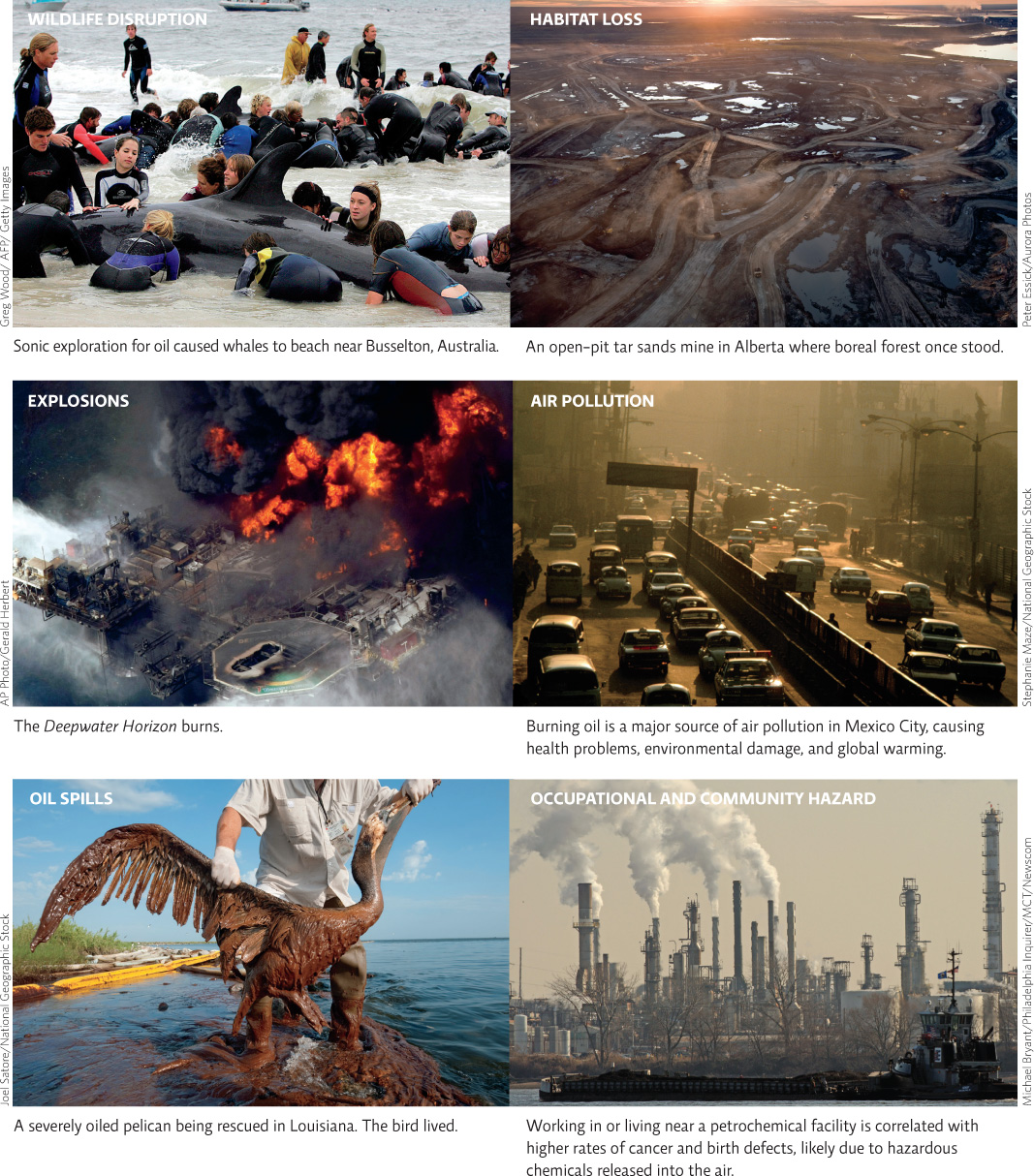

Fossil fuel extraction and use comes at a high environmental cost.

Oil extraction is not just financially expensive; it also has environmental consequences at almost every stage. In order to find oil, companies send seismic waves into the ground that bounce back to reveal the location of possible reserves. Doing this in ocean areas disorients marine wildlife; in 2009, ExxonMobile had to abandon its oil exploration in Madagascar because more than 100 whales had beached themselves, presumably as a result of these seismic exploratory methods.

368

KEY CONCEPT 19.5

Fossil fuels are incredibly useful and versatile chemicals, but their extraction, processing, transport, and use damage the environment and affect human health.

Drilling can affect wildlife, too. Politicians have long debated the merits of drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR), 8 million hectares (20 million acres) of protected wilderness that was created by Congress under the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act of 1980. The USGS estimates that parts of ANWR located on the northern Alaskan coast could harbor between 5 and 16 billion barrels of technically retrievable crude oil and natural gas reserves. But drilling there would have serious environmental consequences. The coastal area where drilling would take place is home to Arctic foxes, caribou, polar bears, and migratory birds, all of whose habitats could be disturbed by drilling.

Of course oil spills—an unintended but frequent consequence of oil drilling and transport—can have immediate and long-term effects. Thankfully, large-scale accidents like the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil platform explosion and oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico are rare, but unfortunately, they can be devastating. The Deepwater Horizon spill eventually covered 930 square kilometers (360 square miles) of ocean, impacted roughly 1,800 kilometers (1,100 miles) of coastlines, and infiltrated and damaged coastal wetlands. The oil threatened the lives of many species, including sea and shore birds; thousands of dead or oiled birds were recovered. In addition, it threatened several species of endangered sea turtles, which feed and live in the waters affected by the spill; hundreds of dead turtles were collected in the area. Exposure to spilled oil causes deformities in young fish, including important commercial species such as bluefin tuna that spawn in the area; numbers of bluefin larvae fell by 20% after the spill. Deep-water coral communities as far as 22 kilometers (14 miles) from the spill site show dead and injured coral, with damage indicative of exposure to oil. And while bacteria did help break down and digest much of the oil, a 2014 study conducted by Florida State University researchers found that the bacteria did not consume the more highly toxic chemicals in the oil (a class of chemicals known as polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons).

369

The Deepwater Horizon disaster also disrupted the livelihoods of residents and those in the fishing and tourism industries. The closure of commercial fisheries resulted in an estimated loss of more than $4 billon, about 40% of an average year’s revenue. Some fisheries, notably the oyster fishery, have yet to recover their pre-disaster productivity. Tourism was also affected: Although it’s difficult to really put a price on the financial losses to all the large and small business affected, losses were estimated at $3.8 billion over a 3-year period. Litigation and criminal trials are still under way regarding the Deepwater Horizon disaster.

The hazards of oil are not limited to exploration, extraction, and transportation of oil. Burning fossil fuels releases a variety of air pollutants that are linked to negative ecosystem and health impacts. It is also the number-one anthropogenic contributor to climate change. (See Chapter 20 for more on air pollution and Chapter 21 for more on climate change.) In addition, working with oil is a hazardous undertaking, even when the required precautions are taken. Workers in the petroleum chemical industry have much higher rates of cancer, rashes, heart disease, and various other health problems than the general population. This hazard extends to people living near oil refineries and petrochemical plants; rates of cancer, birth defects, headaches, and asthma in such areas exceed national averages. The reality is that working with fossil fuels is a hazardous undertaking, even when state and federal regulations are met, and they often are: Most workers do not intentionally or carelessly expose communities or the nearby environment to hazards. INFOGRAPHIC 19.6

ENVIRONMENTAL COSTS OF OIL

Oil has environmental costs at every stage—from exploration for reserves, to extraction, processing, transportation, and burning. If these, often externalized, costs were added to the price of our fuel and petroleum-based goods, the prices of these products would be much higher.

Greg Wood/AFP/Getty Images

Peter Essick/Aurora Photos

AP Photo/Gerald Herbert

Stephanie Maze/National Geographic Stock

Joel Satore/National Geographic Stock

Michael Bryant/Philadelphia Inquirer/MCT/Newscom

What could be done to decrease each of the impacts shown here?

Answers may vary but might include: WILDLIFE DISRUPTION BY SONIC EXPLORATION: development of new methods that use sonic exploration in frequencies not heard by wildlife; HABITAT LOSS: pursue only those methods with a smaller “footprint” (this pretty much eliminates tar sands mining); AIR POLLUTION and OCCUPATIONAL/COMMUNITY HAZARDS: clean up emissions before release and decrease overall use of oil and natural gas; EXPLOSIONS, OIL SPILLS, and OCCUPATIONAL/COMMUNITY HAZARDS: better safety protocols and oversight.

Natural gas (predominantly methane) is an important alternative to oil for some purposes, like generating electricity and heat. But according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), which tracks and analyzes energy data for the Department of Energy, natural gas consumption is expected to increase more than 18% by 2030, an increase with which our current conventional reserves just can’t keep up.

The extracting and processing methods for natural gas and oil are very similar. Natural gas sometimes flows freely up wells due to underground pressure, but most natural gas contains impurities and must be refined before it can be used. It is often “flared off” at the oil well in areas where capturing the gas is uneconomical (usually because the wells are not close to pipelines or processing facilities that could transport and process the captured gas), a waste of a potentially useful resource. Natural gas is considered the cleanest fossil fuel because it releases much less carbon dioxide (a greenhouse gas linked to climate change) and other air pollutants than oil or coal do when burned. Ironically, natural gas is itself a potent greenhouse gas. Capturing it or flaring it off is preferable to releasing it into the atmosphere.