Humanity faces some challenges in dealing with environmental issues.

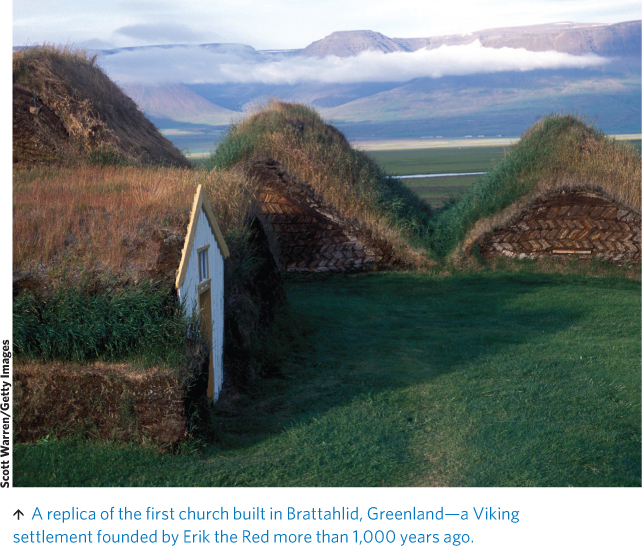

Experts agree that if the Greenland Vikings had simply switched from cows to fish, they might have avoided their own demise. Such a switch would have saved at least some of the pastureland, not to mention the tremendous amount of time and labor it took to raise cattle in such an ill-suited environment. But cows were a status symbol in Europe, beef was a coveted delicacy, and for reasons that still elude researchers, the Vikings had a cultural taboo against fish. It was a taboo they clung to, even as they starved to death.

KEY CONCEPT 1.7

Environmental literacy helps us understand and respond to environmental problems. Impediments to solving environmental problems include social traps, wealth inequities, and conflicting worldviews.

“It’s clear that the Vikings’ decisions made them especially vulnerable to the climatic and environmental changes that descended upon them,” says McGovern. “When you’re building wooden cathedrals in a land without trees, when you create a society reliant on imports in a situation where it’s difficult to travel back and forth between the homeland, when you absolutely refuse to collaborate with your neighbors in such a harsh, unforgiving environment, you are setting yourself up for trouble.” Ultimately, he says, the decisions this society made played as much of a role in its demise as the actual environmental changes did.

The problem, McGovern says, is not that the Greenland Vikings made so many mistakes in their early days but that they were unwilling to change later on. “Their conservatism and rigidity, which we can see in many different aspects, seems to have kept them on the same path, maybe even prodded them to try even harder—build bigger churches, etc.—instead of trying to adapt.”

“It’s clear that the Vikings’ decisions made them especially vulnerable to the climatic and environmental changes that descended upon them.”

—Thomas McGovern.

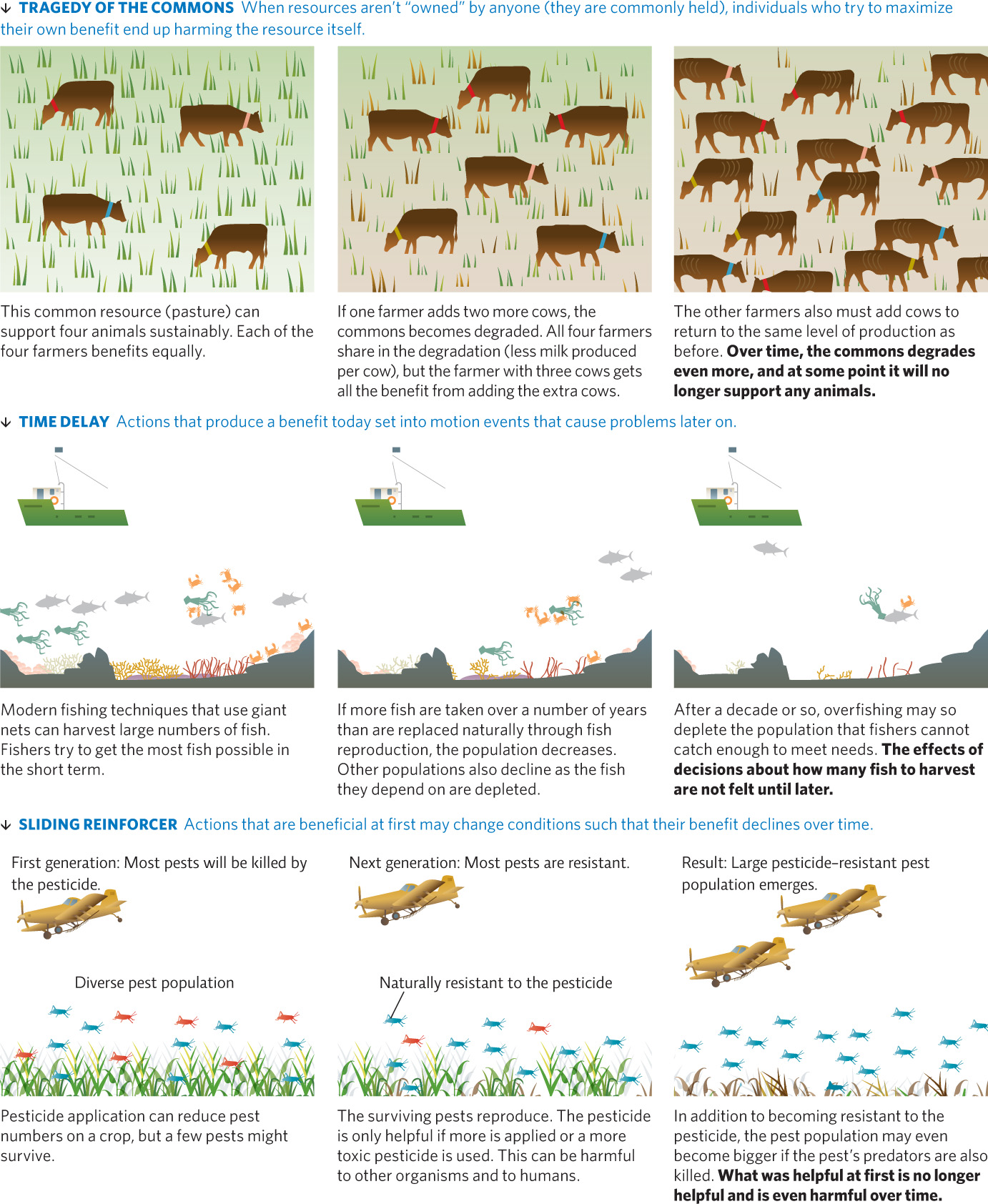

Decisions by individuals or groups that seem good at the time and produce a short-term benefit but that hurt society in the long run are called social traps. The tragedy of the commons is a social trap, first described by ecologist Garrett Hardin, that often emerges when many people are using a commonly held resource, such as water or public land. Each person will act in a way to maximize his or her own benefit, but as everyone does this, the resource becomes overused or damaged. Herders might put more animals on a common pasture because they are driven by the idea that “if I don’t use it, someone else will.” We do the same thing today as we overharvest forests and oceans and as we release toxins into the air and water. Other social traps include the time delay and sliding reinforcer traps—actions that, like the tragedy of the commons, have a negative effect later on. INFOGRAPHIC 1.7

social traps

Decisions by individuals or groups that seem good at the time and produce a short-term benefit but that hurt society in the long run.

tragedy of the commons

The tendency of an individual to abuse commonly held resources in order to maximize his or her own personal interest.

time delay

Actions that produce a benefit today and set into motion events that cause problems later on.

sliding reinforcer

Actions that are beneficial at first but that change conditions such that their benefit declines over time.

SOCIAL TRAPS

Social traps are decisions that seem good at the time and produce a short-term benefit but that hurt society (usually in the long run).

Why do you suppose humans are so prone to being caught in these social traps?

We tend to focus on the short term, rather than the long term. As a social species, we also tend to identify with our own “group” (community, state, country) and are willing to undermine the needs of other “groups” if it advances our own.

Education is our best hope for avoiding such traps. When people are aware of the consequences of their decisions, they are more likely to examine the trade-offs to determine whether long-term costs are worth the short-term gains and, hopefully, to make different choices when necessary. In the United States, environmental laws, such as the Clean Air Act, Clean Water Act, and Endangered Species Act, have gone a long way toward protecting our natural environment from various social traps, but enforcing those laws is a constant challenge.

14

15

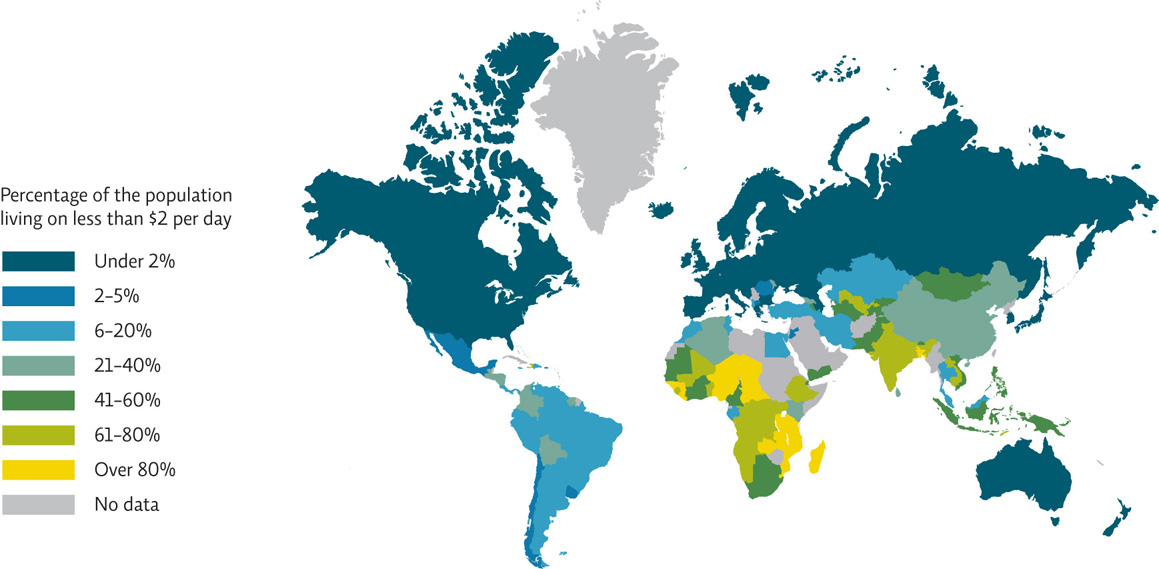

Social traps are not the only challenge societies face. Another obstacle to sustainable growth is wealth inequality—the unequal distribution of wealth (and power) in a community or society. In the Greenland Viking colony, wealth at first insulated the people in power from the environmental problems, and they didn’t feel the strain of the decline (as other, less powerful colony members undoubtedly did) until it was too late. In the same way, wealthier nations today are less affected by resource availability, while 2 billion or more people lack adequate resources to meet their needs. In fact, just 20% of the population controls roughly 80% of all the world’s resources. On one hand, the affluent minority (of which the United States is a part) uses more than its share. Deep pockets allow us to exploit resources for wants, not just needs, and to exploit them all over the world, so that we can spare our own natural environments at the expense of someone else’s. For example, our demand for mahogany furniture drives deforestation in Central and South America, where the tree flourishes. Because we are far away from the trees, the environmental fallout is easy to ignore at the moment, but as it did for the Vikings, it may reach a point where it affects everyone.

On the other hand, the underprivileged also exploit the environment in an unsustainable way. With limited access to external resources, they are often forced to overexploit their immediate surroundings just to survive. The above example applies here, too. For an impoverished landowner in Costa Rica or Brazil, chopping down trees may be the only way she can feed her family; to her, harvesting the forest is more valuable than preserving it.

There are societal costs, as well, to this inequality. A growing gap between the haves and have-nots exacerbates tension and strife all over the world. In fact, fighting over resources has long been one of the contributing factors to societal decline and collapse. INFOGRAPHIC 1.8

WEALTH INEQUALITY

Wealth and power was not evenly distributed in the Greenland Viking colony; a few powerful leaders made decisions that impacted everyone. The same is true today in many regions of the world. The World Bank estimates that about 40% of the world’s population lives on less than $2 a day; almost half of the 2.2 billion children worldwide live in poverty. A small percentage of our population (perhaps 20%) controls 80% of all resources. Actions by the wealthy today that degrade the environment degrade it for all sooner or later.

How might environmental problems differ between wealthy and poorer nations?

Problems in wealthy nations often arise out of the overuse of resources whereas in poorer nations, problems arise out of the lack of resources.

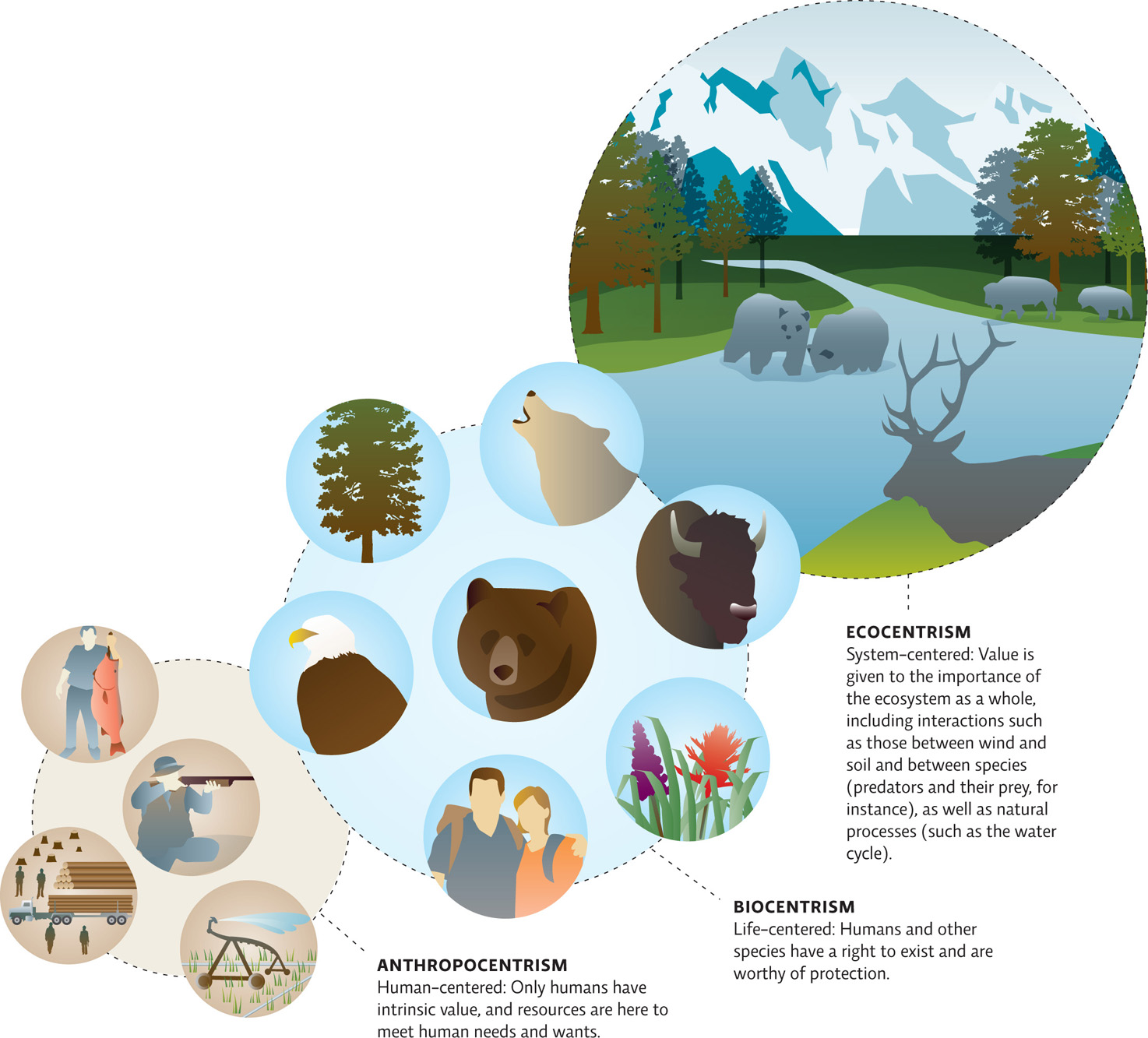

Conflicting worldviews are another challenge to sustainable living. Because our worldviews—the windows through which we view our world and existence—are influenced by cultural, religious, and personal experiences, they vary across countries and geographic regions, even within a society. People’s worldviews determine their environmental ethic, or how they interact with their natural environment; worldviews also impact how people respond to environmental problems. When different people or groups, with different worldviews, approach environmental problems, they are bound to draw very different conclusions about how best to proceed.

worldview

The window through which one views one’s world and existence.

environmental ethic

The personal philosophy that influences how a person interacts with his or her natural environment and thus affects how one responds to environmental problems.

16

The Vikings had an anthropocentric worldview—one where only human lives and interests are important. Meanwhile, the Vikings saw other species as having instrumental value—meaning the Vikings valued them only for what they could get out of them. Forests were nothing more than a source of timber; grasslands a source of home insulation and a feeding ground for cattle.

anthropocentric worldview

A human-centered view that assigns intrinsic value only to humans.

instrumental value

The value or worth of an object, an organism, or a species, based on its usefulness to humans.

A biocentric worldview values all life. From a biocentric standpoint, every organism has an inherent right to exist, regardless of its benefit (or harm) to humans; each organism has intrinsic value. This worldview would lead us to be mindful of our choices and avoid actions that indiscriminately harm other organisms or put entire species in danger of extinction. An ecocentric worldview values the ecosystem as an intact whole, including all of the ecosystem’s organisms and the nonliving processes that occur within the ecosystem. Considering the same forests and grassland from an ecocentric worldview, the Vikings might have decided to protect both, not just for the resources they could harvest but to protect the complex processes that can produce those resources only when they remain intact. INFOGRAPHIC 1.9

biocentric worldview

A life-centered approach that views all life as having intrinsic value, regardless of its usefulness to humans.

intrinsic value

The value or worth of an object, an organism, or a species, based on its mere existence.

ecocentric worldview

A system-centered view that values intact ecosystems, not just the individual parts.

WORLDVIEWS AND ENVIRONMENTAL ETHICS

People’s environmental worldviews describe how they see themselves in relation to the world around them. Their worldview influences their environmental ethic, which in turn influences how they interact with the natural world. We present three common worldviews here (there are others).

What is your own environmental worldview? Does it fall squarely into one of these camps, or is it a combination of two or more?

Answers will vary. This is a good question for student essays or in-class discussion. It is also a good question to revisit at the end of the semester. Worldviews may not change but the individual’s own understanding of why they feel the way they do should deepen. Essays re-written at the end of the semester tend to have more depth and support.

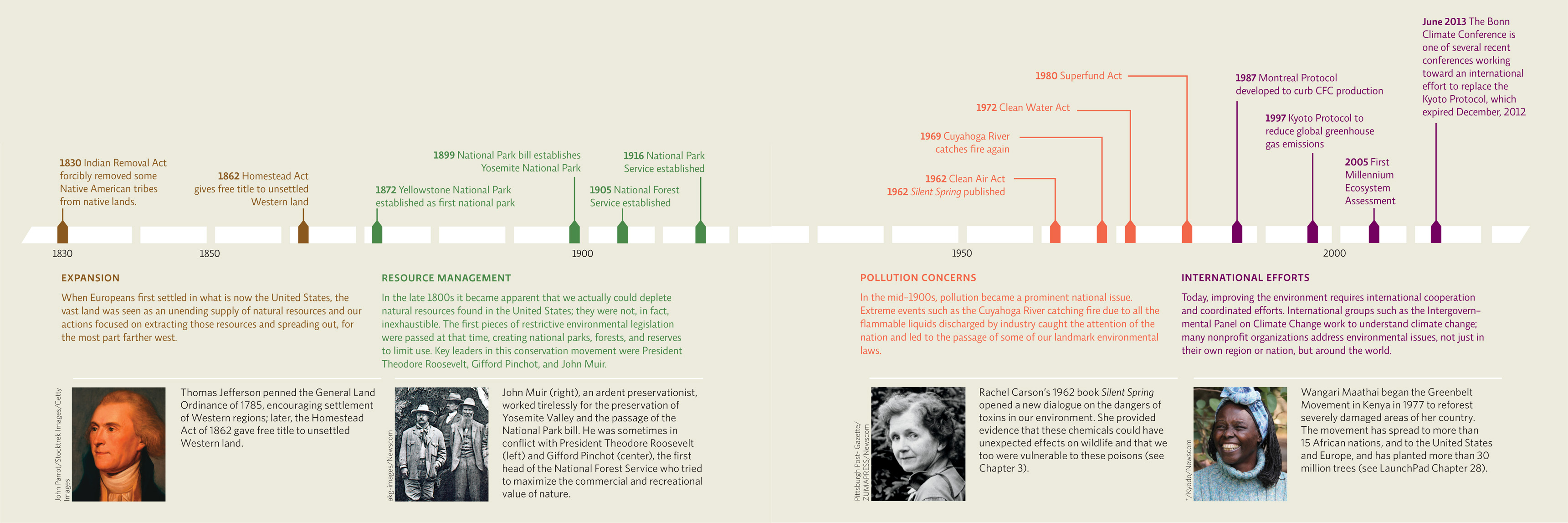

Each of these worldviews may be found among citizens of the United States today, but we can also trace a historical and gradual change in the way a modern nation such as the United States has viewed the natural world. In fact, we can see these worldviews expressed in the ethical positions of many prominent environmental scientists, politicians, and citizens whose actions are associated with landmark events in environmental history. INFOGRAPHIC 1.10

U.S. ENVIRONMENTAL HISTORY

The predominant worldview of a society shapes its actions and the choices made by its citizens at any given point in time. Throughout history, notable individuals with different worldviews have greatly influenced the evolution of our relationship with the natural world. The gradual shift from unrestrained use to focus first on conservation and later on sustainability that was seen in United States and some other developed countries has now become an international movement.

John Parrot/Stocktrek Images/Getty Images

akg-images/Newscom

Pittsburgh Post- Gazette/ZUMAPRESS/Newscom

*/Kyodo/Newscom

How might differing worldviews influence international efforts to address environmental problems?

Differing worldviews could lead to conflict if different groups or nations view problems and solutions differently. Acknowledging the viewpoints of others could be critical in identifying why disagreements occur and better equip us to reach acceptable solutions.

17

18

Back in Greenland, in the silt-covered ruins of a Viking farmhouse, archaeologists found the bones of a hunting dog and a newborn calf, dating back several centuries. The knife marks covering both indicate that the animals were butchered and eaten. “It shows how desperate they were,” says McGovern. “They would not have eaten a baby calf, or a hunting dog, unless they were starving.” By then, it was probably far too late for the Greenland Vikings to adapt in any meaningful way. Their tale had already been written—in ice cores and mud cores and in hundreds of years’ worth of midden heaps.

Our own story is being written now, in much the same way. But unlike our forebears, we still have enough time to shape our own narrative. Will it be dug up, 1,000 years hence, from the ruins of what we leave behind? Or will it be passed down by the voices of our successors, who continue to thrive long after we are gone? Ultimately, the answer is up to us.

Select References:

Benyus, J. (1997). Biomimicry. New York: William Morrow and Company.

Diamond, J. (2005). Collapse. New York: Viking Press.

McGovern, T. H. (1980). Cows, harp seals, and churchbells: Adaptation and extinction in Norse Greenland. Human Ecology, 8(3), 245–275.

19

PERSONAL CHOICES THAT HELP

The concept of sustainability unites three main goals: environmental health, economic profitability, and social and economic equity. All sorts of people, philosophies, policies, and practices contribute to these goals; concepts of sustainable living apply on every level, from the individual to the society as a whole. In other words, every one of us participates. Throughout this book, you will have the opportunity to learn about personal actions that can help address environmental issues, but a good starting place is to learn about your own environment and the place you call home.

Individual Steps

Discover your local environment. What parks or natural areas are close by? Does your campus have any natural areas? Visit one and spend a little time observing nature and your own reactions. Write down your thoughts or share you experiences with a friend.

Are there restaurants, grocery stores, or other retail venues accessible through public transportation or within walking distance of your campus or home? For a week or two, try walking or riding a bike or bus to these businesses instead of driving to others farther away. Is this a reasonable option for you? Why or why not?

Group Action

Discover your own interests. There is a group for every interest—from outdoor recreation, wildlife viewing and preservation, and environmental education, to transportation and air-quality issues. Get involved with organizations working to improve environmental issues or address social change and human rights. One person can make a difference, but a group of people can cause a sea of change.

Policy Change

Discover what’s happening in your community. Read the newspapers and monitor blogs covering environmental and quality-of-life issues. Alert your local, regional, and national representatives about the issues you care about and vote for government officials who support the causes you support.

20