Air pollution is responsible for myriad health and environmental problems.

Outdoor air pollution, in all forms, is one of the most dramatic contributors to asthma. When the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) started regulating air pollution, the agency did not know the extent to which air pollution could affect health; in fact, the EPA administrator noted at the time that the agency’s clean air regulations were “based on investigations conducted at the outer limits of our capability to measure connections between levels of pollution and effects on man.” Nevertheless, in 1971, the EPA set standards for the most common but problematic pollutants—known as criteria air pollutants. Five of these were chemical air pollutants: carbon monoxide, sulfur dioxide (SO2), nitrogen oxides (NOx), lead, and the secondary pollutant ground-level ozone; standards were also set for particulate matter (PM)—particles or droplets small enough to remain aloft in the air for long periods of time. Although all particulates reduce visibility, it is the smallest particles—those with a diameter less than 2.5 micrometers (μm), about 1/40 the diameter of a human hair—that aggravate asthma and other chronic lung diseases and increase the risk for death. INFOGRAPHIC 20.2

OUTDOOR AIR POLLUTION

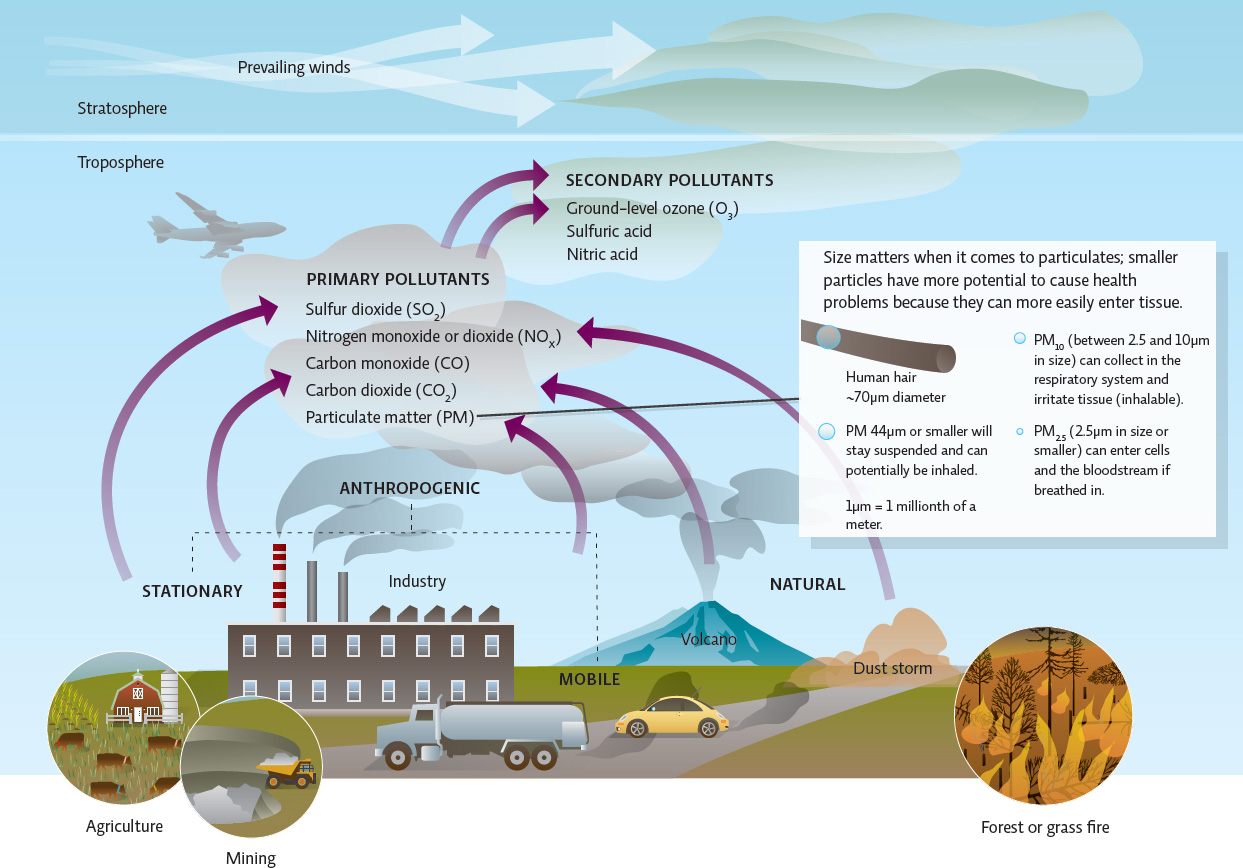

There are many sources of outdoor air pollution, both natural and anthropogenic. These sources release primary pollutants, some of which may be converted to different chemicals (secondary pollutants). Prevailing winds transport pollution that reaches the upper troposphere or stratosphere around the globe; no area is immune to air pollution. Agricultural and industrial pollutants have been found in Arctic and Antarctic air, delivered by these prevailing winds.

Identify the sources of pollution shown in this infographic as either natural or anthropogenic.

Natural sources are volcanos, dust storms and forest or grass fires. Anthropogenic sources are industry, vehicles, agriculture, and mining.

particulate matter (PM)

Particles or droplets small enough to remain aloft in the air for long periods of time.

387

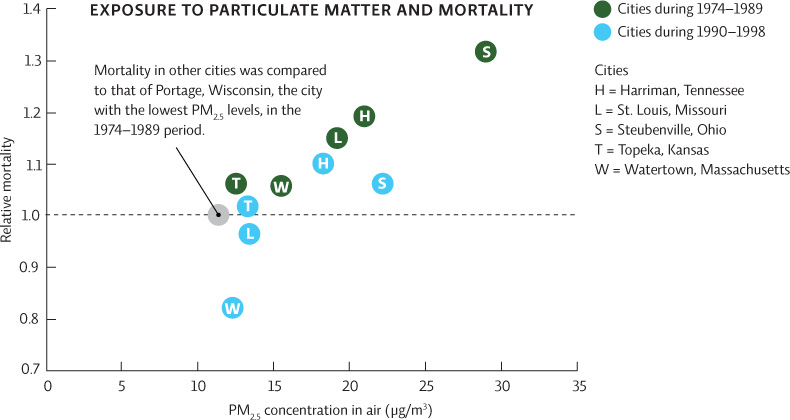

With the exception of lead (whose levels have dropped significantly since the passage of the Clean Air Act), these criteria pollutants are still considered the most problematic and health-threatening pollutants in the United States. A 1993 study published by Harvard University researchers helped establish the link between air pollution and impaired health. A follow-up study in 2006 estimated that particulate pollution—which includes soot, ash, dust, smoke, pollen, and small, suspended droplets (aerosols)—accounts for 75,000 premature deaths per year and showed a clear dose-response effect: The higher the air pollution, the higher the risk for death. INFOGRAPHIC 20.3

THE HARVARD SIX CITIES STUDY LINKED AIR POLLUTION TO HEALTH PROBLEMS

To see if there was a link between health and small particulate pollution (PM2.5; that is, particulate matter smaller than 2.5 micrometers), researchers at Harvard University compared death rates and PM2.5 levels in six U.S. cities. The data reveal that as particulate pollution increases, so does the mortality (death) rate. PM2.5 pollution and deaths went down in every city between the two sampling periods evaluated—likely a result of stricter pollution limits in the 1990s.

In this graph, what does it mean to say that the relative mortality rate of Steubenville, Ohio, was 1.3? Identify the concentration of particulate matter in Steubenville, Ohio, during the first time period (1974–1989) and the morality relative to the comparison city, Portage, Wisconsin. Now do the same for Steubenville in the second time period (1990–1998). How much did each parameter change over the course of the study? For every 100 people who died in Portage between 1990–1998, how many died in Steubenville?

A relative mortality rate of 1.3 means that for every person who died in Portage, WI (the comparison city), 1.3 died in Steubenville. (Or, since 1.3 people cannot die, you could say: For every 10 people who die in Portage, 13 died in Steubenville.) Between 1974-1989, Steubenville’s particulate pollution level was about 28 µg/m2; its mortality relative to Portage was slightly more than 1.3. In 1990-1998, its particulate pollution level was about 22 µg/m2; its morality relative to Portage was about 1.08. Particulate pollution fell by 6 µg/m2 and relative mortality fell by 0.22. This means, compared to 100 deaths in Portage, only 108 died in Steubenville, rather than the 130 who would have died in the earlier time period.

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 8 million people die prematurely each year as a result of exposure to air pollution. Respiratory ailments are common because particulates from soot and smog damage respiratory tissue and increase susceptibility to infection. In addition, research has shown that asthma rates are higher in people who breathe polluted air—and children are particularly sensitive because they breathe in more air for their size than adults do and because developing tissue is more vulnerable.

Delfino’s team of researchers followed up their first study with a second in 2007 that included 53 students with asthma (ages 9–18) with air monitors strapped to their backs. The students also had to breathe into detectors that recorded how much air they were able to blow out from their lungs at once—a measure of lung function. The results suggested that high levels of particulate pollution actually decrease lung function. More recent studies have shown a positive correlation between the amount of air pollution exposure and lung inflammation as well as the number of hospital visits.

KEY CONCEPT 20.3

Air pollution causes health problems, damages structures, reduces visibility, and contributes to stratospheric ozone depletion and climate change.

Lungs are particularly vulnerable to these small particulates because they get so much exposure (we breathe all the time) and the tissue itself is delicate. Irritants like particles, dust, and pollen can cause the lungs to produce excess mucus in an attempt to trap and expel the irritant. The lining of the airways can become inflamed and swell; in people with asthma, the irritation may trigger muscle contractions that close off the airway completely. Particles smaller than 2.5 μm can actually penetrate cells of the lungs or enter the bloodstream, where they are delivered to other cells of the body. If these particles come from the combustion of fossil fuels or other industrial sources, they may contain toxic substances, leading to problems associated with toxic exposure.

388

The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 8 million people die prematurely each year as a result of exposure to air pollution.

Since the cardiovascular system depends on the respiratory system to provide oxygen for the body, anything that impairs the lungs also harms the cardiovascular system, which might explain the fact that people living in polluted areas also have higher rates of heart attacks and strokes. Cancer rates are higher in people exposed to air pollution, too; exposure to secondhand smoke and exposure to radon are the leading environmental causes of lung cancer, and exposure to smog and vehicle emissions is linked to increased risk for lung and breast cancer.

Researchers have also found that air pollution affects not only the adults and children who breathe it in but it also affects unborn babies. Maternal exposure to air pollution causes babies to be born prematurely and with low birth weight, in part due to the fact that air pollution increases the risk that a pregnant woman will suffer from preeclampsia, a form of pregnancy-related hypertension. Prenatal exposure to polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs)—air pollutants released as by-products from the combustion of wood, tobacco, coal, or diesel—is linked to birth defects. “We have learned that PAHs end up in the placenta and fetus,” explains Beate Ritz, an epidemiologist at the University of California, Los Angeles, School of Public Health.

389

But humans aren’t the only creatures suffering the ill effects of air pollution. Many animals suffer the same respiratory distress as humans: All lung (and gill) tissue is very vulnerable to air pollution. Invertebrates as a group, especially aquatic ones, seem to be more directly impacted by air pollution (toxic effects or reproductive declines) than are vertebrates. But aquatic vertebrates like fish and amphibians are certainly feeling severe impacts. Declines in North Atlantic salmon populations have been linked to air pollution-induced water acidity. The higher acidity causes aluminum to build up in water; aluminum is toxic to fish, especially juvenile salmon.

Plant tissues are also vulnerable to pollutants like smog and ozone, which cause direct damage to sensitive cell membranes. Exposure can damage a leaf’s ability to photosynthesize, preventing healthy growth and compromising its survival. Lichens are particularly vulnerable to air pollution such as nitrogen emissions (NOx), and their decline is seen as a warning of the potential for damage to forests and crops. Together with changes in soil chemistry—which can hinder plant growth—pollution damage to plant crops will ultimately cause global crop yields to fall. Estimates of crop yields predict decreases for soybean, wheat, and maize ranging from 4% to 26% by 2030, amounting to dollar losses in the billions.

Finally, pollution damages buildings and monuments. Acid in polluted rain literally eats away at limestone and marble structures; it can etch glass and damage steel and concrete, causing billions of dollars of damage per year. Smog, SO2, and ground-level ozone pollution also lower visibility by creating haze, a concern for areas that depend on tourism. On hazy days, for instance, it can be impossible to see across the Grand Canyon.