Confronting climate change is challenging.

Jack Rajala’s timber company owns 14,000 hectares (35,000 acres) of commercial forest land in Itasca County, Minnesota. In recent years, he’s started doing things differently—namely, deliberately thinning out his paper birches in an effort to cultivate more oaks and white pines. This is not to say that the paper birch isn’t valuable. But with massive die-offs under way throughout the region, Rajala needs to hedge his bets. “We think we can still facilitate birch,” he said. “But it may be an understory tree, not a canopy tree anymore.”

Rajala’s strategy is called resistance forestry; it includes a handful of techniques aimed at maintaining existing species in their current locations, even as the climate shifts. For example, prescribed burns that mimic historic fire patterns might bolster the ranks of fire-dependent species like paper birch, black spruce, and jack pine, allowing them to spread over a wider area and enhancing their genetic diversity. Planting seeds instead of saplings also helps species hold their ground; natural selection favors the hardiest field-grown seedlings and so may yield a population better able to survive environmental stresses.

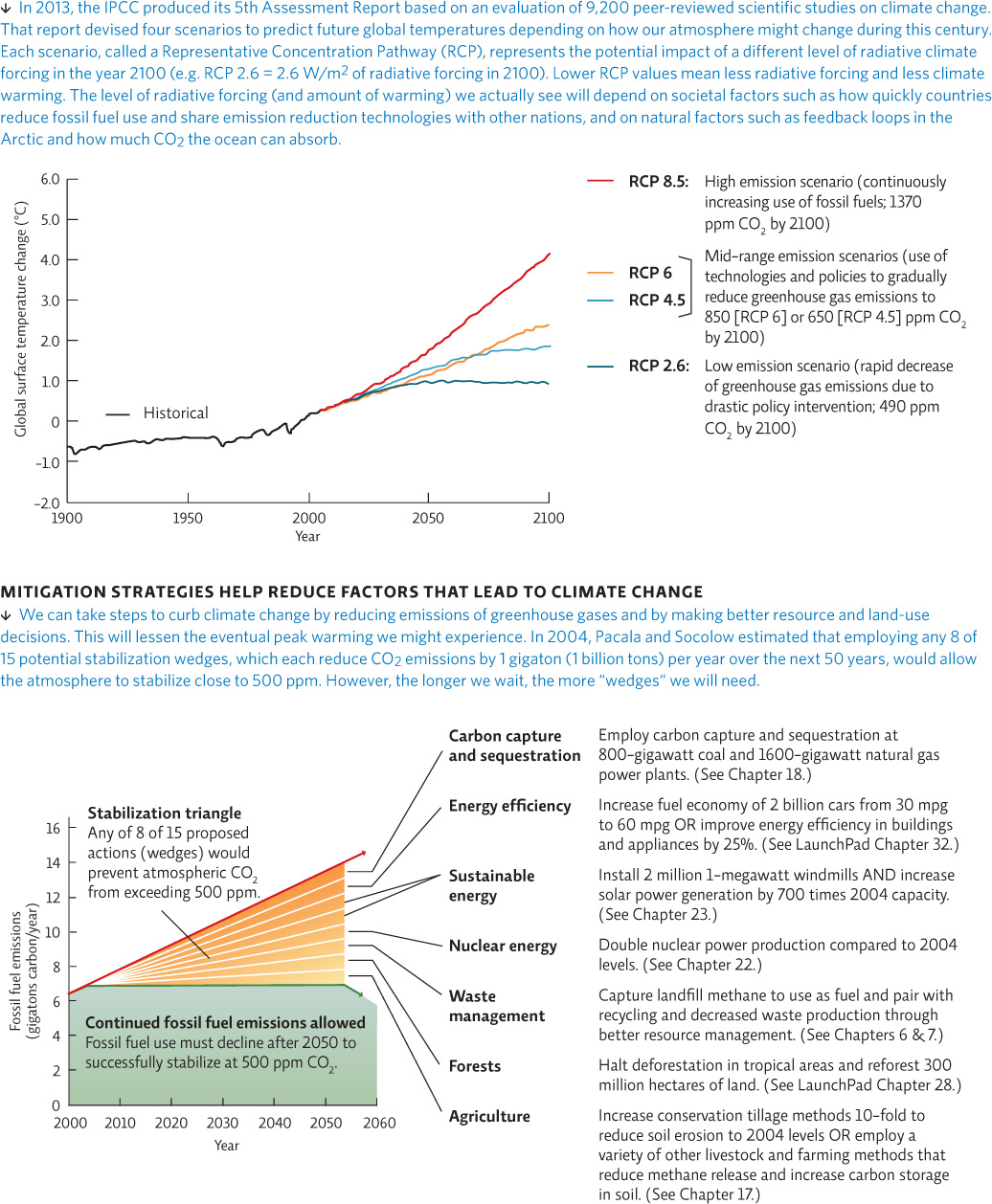

Scientists refer to such efforts, which are intended to minimize the extent or impact of climate change, as mitigation. Mitigation includes any attempt to seriously curb the amount of CO2 we are releasing into the atmosphere—either by using carbon capture techniques to remove the greenhouse gas from our air and sequester it underground or by consuming fewer fossil fuels to begin with. In 2004, Princeton University researchers Stephen Pacala and Robert Socolow proposed a “stabilization wedge” strategy—a step-by-step implementation of currently available technology; each step could prevent the release of 1 billion tons of carbon. At the time of their paper’s publication, Pacala and Socolow estimated that any 8 of the 15 steps, or “wedges,” would stabilize CO2 in the atmosphere at close to 525 ppm in the next 50 years. Today, more wedges would be needed (since more CO2 is in the air), especially if we aim for a target of 450 ppm CO2. But the good news is that we already have at our disposal the means to seriously reduce CO2 emissions. INFOGRAPHIC 21.10

FUTURE CLIMATE CHANGE DEPENDS ON OUR CURRENT AND FUTURE ACTIONS

Which stabilization wedge do you think would be the easiest to accomplish? Which would be the hardest?

Answers will vary but should be supported.

mitigation

Efforts intended to minimize the extent or impact of a problem such as climate change.

422

KEY CONCEPT 21.12

Responding to climate change will require both steps that try to reduce future warming (mitigation) and steps to deal with inevitable warming (adaptation).

On a national or global scale, mitigation efforts can be facilitated in a variety of ways, such as command-and-control regulations that limit greenhouse gas release; tax breaks; green taxes (in this case, carbon taxes); and market-driven programs such as carbon cap-and-trade (see Chapter 20). Financial incentives that encourage the development and use of non-carbon fuels and more energy-efficient technology will be critical (see Chapters 22, 23, and 24).

carbon taxes

Governmental fees imposed on activities (such as fossil fuel use) that release CO2 into the atmosphere.

No matter which strategies we employ, curbing greenhouse gas emissions will take a coordinated global effort, meaning that world superpowers like the European Union, the United States, and China will have to cooperate with the developing nations of the world. So far, efforts have been fraught with obstacles and lack of cooperation. In 1997, an international treaty called the Kyoto Protocol was ratified by every UN nation except the United States. The treaty set different but specific targets for the reduction of CO2 emissions for various countries; the United States objected because the protocol set much higher reduction requirements for developed countries (which were responsible for most of the historic emissions) than it did for developing countries.

Additional criticisms of Kyoto underscore the trouble with confronting such a global problem. Some of those who opposed Kyoto said that it went way too far in curbing greenhouse gas emissions; they argued that placing any kind of limit on CO2 would hurt the economy because it would force industries to spend money updating their infrastructure, limit the amount of work they could do, and place them at a disadvantage compared with countries that had lower reduction targets under the treaty.

Other critics said that Kyoto did not go far enough. Given the overwhelming evidence, these critics felt we needed to set much higher reduction targets to make any dent in the problem. They also felt that setting concrete, legally binding reduction targets in developed countries like the United States would actually stimulate the economy because it would force companies in those countries to develop new, cleaner, more efficient technologies that other countries would then buy.

Taking steps to address greenhouse gas emissions will certainly cost money, but a 2014 study by researchers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology showed that these steps will actually save money when the health benefits of controlling air pollution are factored in (since steps that reduce greenhouse gas emissions also reduce our exposure to particulate matter and ground-level ozone). For example, the study reported that while a carbon cap-and-trade system might cost the United States $14 billion to implement, it would save 10 times that amount thanks to decreased health care costs and fewer employee sick days. In a press release, lead author Tammy Thompson said, “If cost—benefit analyses of climate policies don’t include the significant health benefits from healthier air, they dramatically underestimate the benefits of these policies.”

Combatting climate change challenges the bedrock of modern civilization: energy use. Some argue that applying the precautionary principle now could help avoid, or at least lessen, some of the most serious consequences of a changing global climate.

precautionary principle

Acting in a way that leaves a safety margin when the data is uncertain or severe consequences are possible.

The conflicting views on Kyoto also illustrate why climate change is considered a wicked problem—one that is resistant to resolution because it is fraught with complexity, change, incomplete information, and lack of sociopolitical acceptance (see Infographic 1.3). Indeed, the contention over climate change resides in the industrial and political sphere. Energy corporations and their backers have spent millions of dollars on campaigns designed to sow seeds of doubt. Naomi Oreskes and Erik Conway, science historians at Harvard University and California Technical Institute, respectively, reported in their 2010 book, Merchants of Doubt, that these campaigns are spearheaded by some of the same individuals who, at the behest of the tobacco industry, mounted campaigns that effectively raised doubt that smoking was a health hazard. Among other things, they claimed that science had insufficient evidence to conclude that smoking was bad for one’s health.

These same tactics give fodder to climate skeptics. While an estimated 97% of scientists agree with the conclusion that climate is changing and that this change is due to human impact, a small but vocal percentage of scientists, along with individuals from industry and some conservative “think-tanks,” are managing to stymie effective or far-reaching U.S. responses to climate change. They do so by raising doubt, dragging out long-discounted arguments, demanding more certainty before acting, and spending heavily on political campaigns and lobbying efforts.

423

424

The Kyoto Protocol expired on December 31, 2012; so far, despite annual meetings, the international community has had no success in drafting a replacement treaty. The 2011 UN Climate Change Conference in Durban, South Africa, resulted in a legally binding agreement to adopt a future international climate treaty by 2015; subsequent annual conferences are laying the groundwork for a new treaty. Some nations (including Germany and the United Kingdom) have made their own progress toward CO2 reductions, but other nations (including China and India) have seen increases in annual CO2 emissions. U.S. emissions dropped slightly after the 2007 recession but are beginning to creep back up.

Meanwhile, change is coming to the North Woods. And as birches die off and maples try to expand their territory, as moose falter and pine beetles thrive, those who know the woods best say that mitigation will not be enough.

425

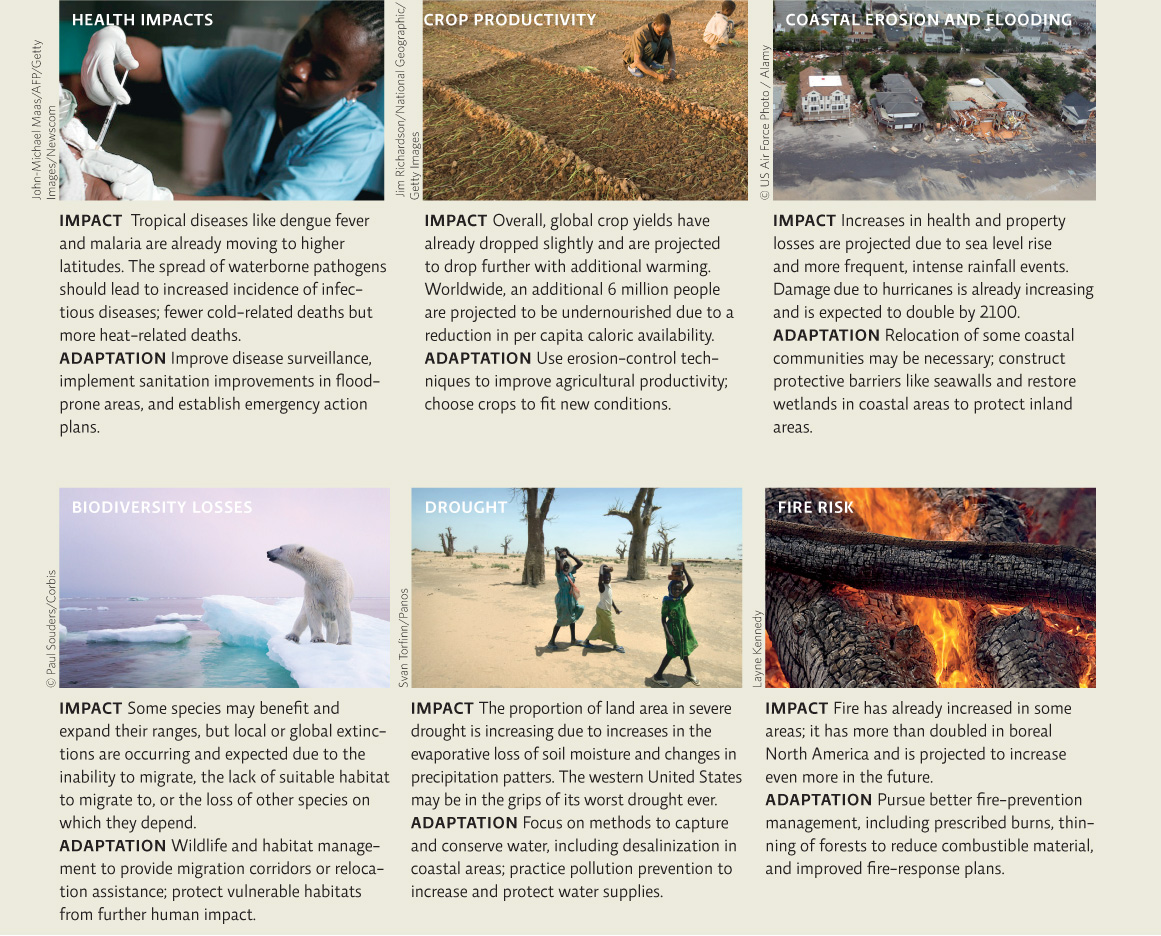

“Resisting climate change at this point is like paddling upstream,” said Frelich. “It might buy us some time, but it’s not going to save the day.” So, he said, we need to start thinking about adaptation: responding to the climate change that has already occurred or will inevitably occur. For human societies at large, this means taking steps to ensure a sufficient water supply in areas where freshwater supplies may dry up; it means planting different crops or shoring up coastlines against rising sea levels; it means preparing for heat waves and cold spells and outbreaks of infectious diseases. INFOGRAPHIC 21.11

CURRENT AND POTENTIAL CLIMATE CHANGE IMPACTS AND ADAPTATION STRATEGIES

No matter how hard we try, we will not be able to avoid some future warming, as greenhouse gases emitted in the 20th century will continue to impact climate into the future. Adaptation strategies equip us to adjust to the inevitable warming that will occur.

John-Michael Maas/AFP/Getty Images/Newscom

Jim Richardson/National Geographic/Getty Images

© US Air Force Photo/Alamy

© Paul Souders/Corbis

Svan Torfinn/Panos

Layne Kennedy

Which impacts concern you the most? Explain.

Answers will vary but should be supported.

adaptation

Efforts intended to help deal with a problem that exists, such as climate change.

In the North Woods, it might mean facilitation—moving tree species to entirely new ranges where they don’t currently grow, based on the notion that the speed of climate change will make it impossible for natural tree migratory processes, such as seed dispersal, to occur. “The idea is that if we want the forest to adapt, we will have to help it along,” said Frelich.

Facilitation has no shortage of critics, many of whom say such tinkering is both dangerous and unnecessary. “Facilitation is my nightmare,” said John Almindinger, a forest ecologist with Minnesota’s Department of Natural Resources. “That we’ll start to believe we’re smart enough to figure out how to move things. It’s sheer hubris.” Besides, he said, many if not most tree species seem to be moving just fine on their own, along traditional forest migration routes. So far, the U.S. Forest Service agrees; the agency does not allow such bold interventions as planting pines inside the wilderness.

Still, some skeptics are coming around to the idea. “We’ve changed the landscape through development and agriculture,” said Peter Reich, a colleague of Frelich at the University of Minnesota. “And we’ve changed the climate, too, with fossil fuel consumption. So we might now need to change the way we manage wild lands to compensate.”

On this much, everyone seems to agree: If northern Minnesota is to remain fully forested in the coming century, something will have to be done. “We see it already,” said Rajala. “The impact of climate change will be too big to just let nature take its course.”

Select References:

Beaubien, E., & A. Hamann. (2011). Spring flowering response to climate change between 1936 and 2006 in Alberta, Canada. BioScience, 61(7): 514–524.

Frelich, L., & P. Reich. (2010). Will environmental changes reinforce the impact of global warming on the prairie–forest border of central North America? Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment, 8(7): 371–378.

Hitch, A., & P. Leberg. (2007). Breeding distributions of North American bird species moving north as a result of climate change. Conservation Biology, 21(2): 534–539.

IPCC. (2013). Climate Change 2013: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Fifth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Stocker, T. F., et al (eds.)]. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

NOAA National Climatic Data Center. (2012). State of the Climate: Global Analysis for Annual 2012. www.ncdc.noaa.gov/sotc/global/2012/13.

Oreskes, N., & E. Conway. (2010). Merchants of Doubt. New York: Bloomsbury Press.

Pacala, S., & R. Socolow. (2004). Stabilization wedges: Solving the climate problem for the next 50 years with current technologies. Science, 305(5686): 968–972.

Thomas, C. D., et al. (2004). Extinction risk from climate change. Nature, 427(6970): 145–148.

Woodall, C. W., et al. (2009). An indicator of tree migration in forests of the eastern United States. Forest Ecology and Management, 257(5): 1434–1444.

PERSONAL CHOICES THAT HELP

The effects of climate change are already being felt by humans, other species, and ecosystems around the globe. Individuals and community groups can make choices that decrease the production of greenhouse gases and increase the removal of CO2 from the atmosphere. This will show policy makers that citizens are interested in preventing global climate change.

Individual Steps

Do your part to reduce carbon emissions by conserving energy. Walk or ride a bike instead of driving a car. Share a ride with a coworker rather than driving alone. Negotiate with your employer to telecommute. Live close to where you work or go to school. Reduce your heating and cooling energy use and always turn off electronics and lights when not in use.

If your utility company offers renewable energy, buy it.

Reduce the carbon footprint of your food by decreasing the amount of feedlot-produced meat you eat. Buy your food as locally as possible to reduce energy used in transportation.

Go to www.terrapass.com to see how you can offset your CO2 production from your car, your house, and your airplane travel.

Group action

Volunteer to help build a zero-energy Habitat for Humanity home.

Organize a community lecture on climate change with a local university expert or meteorologist as the speaker.

Organize an event at your school or community to raise awareness about global climate change and ways to prevent it. Go to http://350.org to join a current campaign and get other program ideas.

Policy Change

Consider writing, calling, or visiting the offices of your legislators and sharing your views about supporting funding for research and development of clean and renewable sources of energy. In addition, ask that they support the funding of science, especially efforts to understand and confront climate change.

426