Public policies aim to improve life in societies.

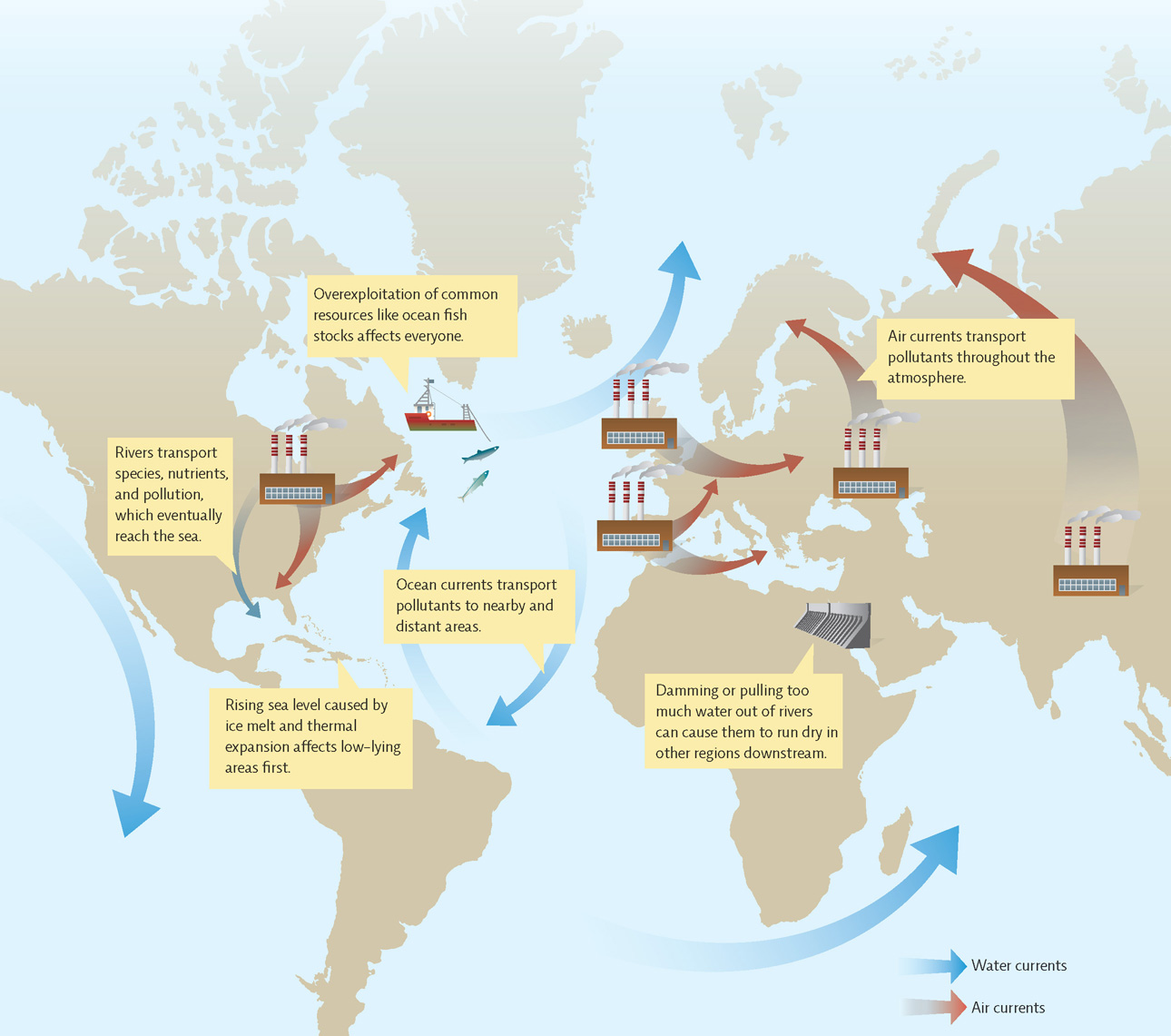

Environmental policies give us guidelines meant to restore or protect the natural environment—sometimes by repairing damaged ecosystems, other times by reducing or mitigating the impact we humans have on our planet. As discussed in Chapter 1, environmental problems are often “wicked problems,” meaning that they tend to be very complex; they have multiple causes and consequences, along with multiple stakeholders. Most of the biggest environmental issues that we now face—like pollution, species endangerment, and climate change—are also transboundary problems; they occur across state and national boundaries. Therefore, solving them requires the cooperation of individual states and countries around the world. INFOGRAPHIC 24.1

environmental policy

A course of action adopted by a government or an organization that is intended to improve the natural environment and public health or reduce human impact on the environment.

transboundary problem

A problem that extends across state and national boundaries; pollution that is produced in one area but falls in or reaches other states or nations.

ADDRESSING TRANSBOUNDARY ENVIRONMENTAL PROBLEMS REQUIRES INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION

National and international policies are needed to address global environmental problems because what happens in one area can affect another. Human impact, such as the transport of non-native species, can have far-reaching consequences. In addition, the atmosphere, rivers, and oceans can very effectively deliver pollution from one area to the next. For example, greenhouse gases released in any part of the world impact global climate. Environmental issues that affect the entire planet require a global response, guided by policies we all agree to follow.

What are some of the difficulties in trying to set and manage policy for international environmental problems?

Different worldviews may affect the definition of a problem or the preferred response so that countries may have a hard time agreeing on a suitable course of action. Political clout is also likely to influence policy making with less powerful countries losing out on policies meant to protect everyone. Enforcement of policies is more difficult on the international level than the national or local level where fines or incarceration may be suitable options but may not work on the international stage. Attributing blame and responsibility is also difficult for far reaching environmental problems with many contributors (such as identifying the sources of ocean or air pollution).

This makes environmental policy tricky. From the start, lawmakers must juggle a handful of potentially daunting factors: effectiveness, or whether the policy can attain the desired goal; the negative trade-offs that might result from the policy; who will absorb the cost burden (external and internal costs) of the policy, for both its enactment and its after-effects; and whether the policy is flexible enough to accommodate changes—the task of adaptive management. Even once all those hurdles are cleared, another remains, and it’s often the largest of the bunch: public support. Policies that may be effective, affordable, and flexible can still die before they ever have a chance to be enacted if voters and/or lawmakers don’t agree that they are necessary.

adaptive management

A plan that allows room for altering strategies as new information becomes available or as the situation itself changes.

Within the United States, policy can be set at three basic levels: local, state, and national. Before the 1960s, environmental issues mostly dealt with how best to use resources (see Chapter 1). Addressing pollution or environmental damage was not a key objective. And environmental issues were primarily handled at the state level. To be sure, there were a few environmentally focused federal laws on the books; for example, the Oil Pollution Act of 1924 banned the release of oil into coastal waters. But in general, federal environmental regulations were considered an intrusion on state sovereignty. In fact, most environmental problems were addressed only after the fact, through litigation—an arrangement that too often favored the polluters: It was even more difficult back then than it is today to prove that toxins from a factory or dump that had seeped into the water or permeated the air were killing livestock or causing human illnesses.

Eventually, though, things began to change. Industry grew, and so did pollution. As it did, environmental problems began slipping across state lines, so that water and air pollution from one state affected another. In the 1960s and 1970s, federal legislators, prompted by a massive national outcry, realized that more regulation was needed, and so they devised a new set of policies that could function across state lines: performance standards. By determining how much pollution could be released in the first place, environmental regulation shifted from after-the-fact litigation to prevention. The shift proved effective, and air pollution emissions from industry and vehicles began to drop; since 1970, emissions of the six criteria air pollutants have fallen more than 70%. (See Chapter 20 for more on criteria air pollutants.)

performance standards

Targets that specify acceptable levels of pollution that can be released or exist in ambient (outdoor) air; industries must act to meet these standards.

By 1969, the era of modern environmental policy had begun. That year, with performance standards gaining a foothold, the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) was codified into law. NEPA established environmental protection as a guiding policy for the nation, mandating that the federal government take the environment into consideration before taking any action that might affect it. It also established a process that remains central to environmental regulation where the need for legislation is determined by available scientific evidence, and where various solutions are analyzed and compared, in excruciating detail, before a decision is made.

National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA)

A 1969 U.S. law that established environmental protection as a guiding policy for the nation and required that the federal government take the environment into consideration before taking action that might affect it.

474

KEY CONCEPT 24.2

The NEPA process is a useful guideline for policy making that includes systematically considering all options before setting policy and evaluating policy after it is implemented.

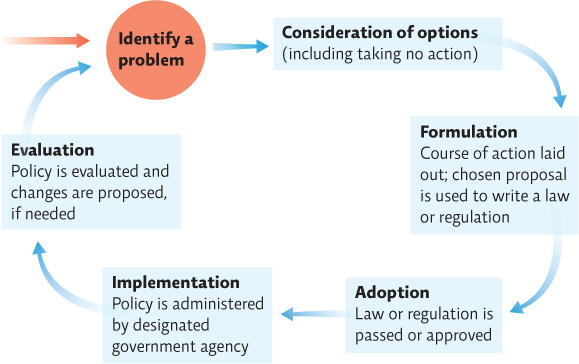

NEPA’s signature feature has been the environmental impact statement (EIS)—a report that details the likely effect of a proposed federal action, such as building a road or upgrading a nuclear facility. The goal of an EIS is to identify problems before they occur so that stakeholders can choose the most acceptable course of action (maybe move that road a few miles to the south to avoid disturbing that forest; maybe don’t build the road at all). To keep the process transparent, the findings are made available to everyone—citizens, policy makers, and special interest groups— and everyone is given a chance to respond (through letters and public hearings). INFOGRAPHIC 24.2

environmental impact statement (EIS)

A document that outlines the positive and negative impacts of a proposed action (including alternative actions and the option of taking no action); used to help decide whether that action will be approved.

POLICY DECISION MAKING—THE NEPA PROCESS

Policies are created and revised using some basic steps that allow policy makers to systematically evaluate the situation and possible responses. The process starts with identifying the problem, considering available options for responding, and evaluating the costs and benefits. A policy is then drafted, further evaluated by interested parties, and, if found acceptable, formally adopted. In the United States, bills must be passed by the House of Representatives and the Senate and then signed by the president to become law. Regulations based on those laws are proposed and administered by regulatory agencies (like the Environmental Protection Agency) in a similar manner. The process itself is responsive and allows for adaptive management—reentering the policy cycle for revision as new or changing information comes to light.

What problems can arise if the language in a U.S. law that the EPA is supposed to enforce is vague or ambiguous?

It will be hard to establish regulations that clearly carry out the intent of the law. This can lead to challenges to the regulations that can tie up proposed action for years.

475

In NEPA’s wake came a wave of iconic legislation, most of it passed with overwhelming bipartisan support. Many of the environmental laws passed in the 1970s have a mechanism that allows individual citizens (or groups—including state governments) to demand enforcement via the citizen suit provision. Violations can be reported; if they aren’t dealt with in a satisfactory manner, the citizen or group can file a lawsuit against the violator (an individual, a private company, or the government—even the regulatory agency mandated to enforce regulation) that has allegedly failed to uphold the existing law.

citizen suit provision

A provision that allows a private citizen to sue, in federal court, a perceived violator of certain U.S. environmental laws, such as the Clean Air Act, in order to force compliance.

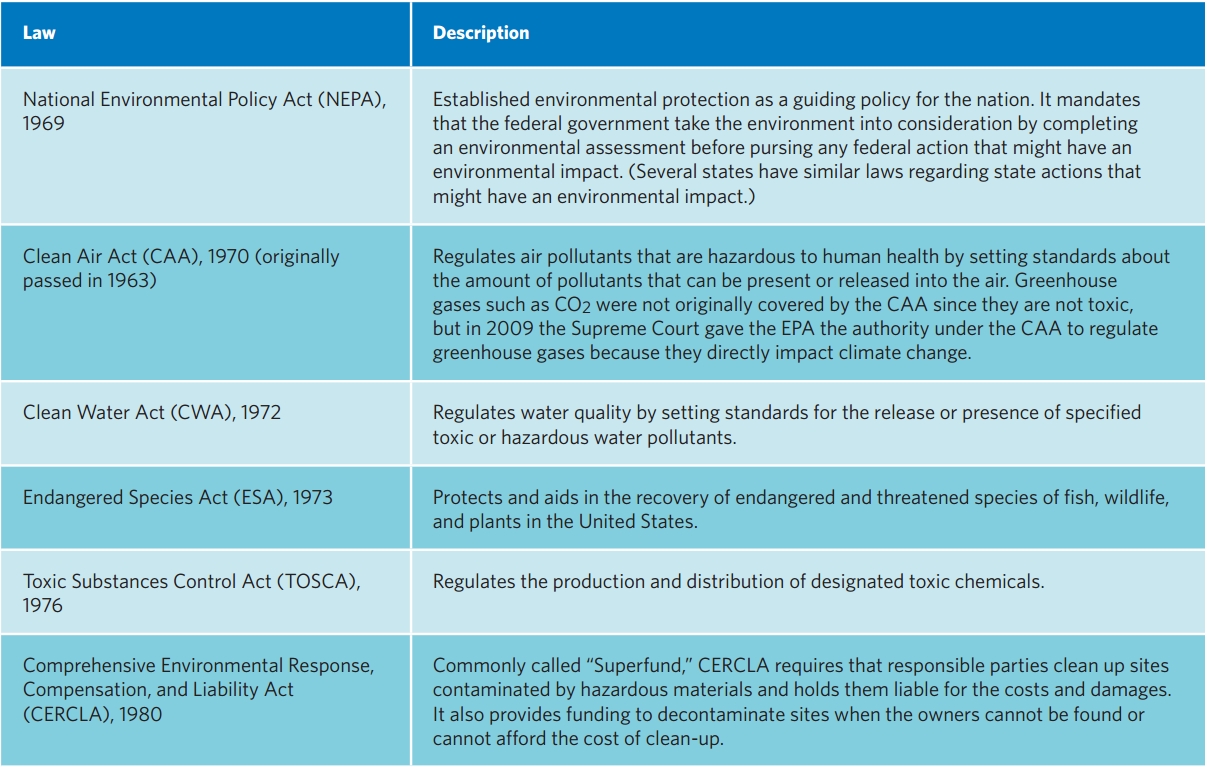

To implement and enforce all these new federal environmental laws, Congress established the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) in 1970. The EPA is a regulatory agency that establishes rules and regulations to support each environmental law as it is passed. EPA officials set the standards which ensure that the goals of any given law are met. They are also tasked with holding individual states and corporations accountable. If a given entity fails to comply with a given rule, the EPA has the authority to step in and mandate changes. It can, for example, force a power plant to make upgrades that decrease pollution, close down a factory for repeated violations, or fine an individual state for failing to curb its vehicle-generated air pollution. It can also force entities to pay clean-up costs and, in certain cases, can revoke operating permits. TABLE 24.1

KEY CONCEPT 24.3

Many iconic U.S. environmental laws originated in the 1960s and 1970s. Some of these laws allow citizens to sue violators to ensure that the laws are properly enforced.

Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)

The federal agency responsible for setting policy and enforcing U.S. environmental laws.

NOTABLE U.S. ENVIRONMENTAL LAWS

In the United States, environmental protection and regulation were originally seen as state issues, but by the middle of the 20th century, it became apparent that many environmental problems crossed state lines and would be best handled through federal legislation. These landmark environmental laws were passed, beginning in the 1960s, during a period of tremendous bipartisan cooperation and support for taking steps to ensure a clean and healthy environment. They have been amended many times to deal with changing or new environmental problems.

Do you feel that these U.S. environmental laws should be strengthened, weakened, or remain as they are?

Answers will vary but should be supported.

Of course, the EPA’s reach extends only to U.S. borders. And, as the case of the coolant factories shows, most environmental problems tend to stretch way beyond those.