Policy making involves many players.

There are currently more than 500 international environmental agreements in effect. They go by a range of names (conventions, accords, agreements, treaties, and so on), regulate a range of human activities, and protect a litany of environmental issues—whaling, fishing, endangered species, and the ozone layer, to name a few. The vast majority of them do what they were intended to do: influence human behavior in ways that protect the natural environment. “Overall, it’s a very methodical and well-done process,” says Stephen Andersen, co-chair of the economic assessment panel for the 1987 Montreal Protocol, which is an international treaty that successfully phased out most ozone-depleting substances (see Chapter 2).

476

Ideally, environmental policy begins with scientific insights gleaned through careful measurement and observation. Those insights come to policy makers through a range of venues: congressional hearings with expert witnesses; federal advisory committees; federally funded research organizations, like the American Association for the Advancement of Science or the Oak Ridge National Laboratory; and in many cases, international scientific organizations like the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the World Meteorological Organization, and the United Nations Environment Programme.

Once a problem (say, a hole in the ozone layer, or an endangered species, or a rapidly warming planet) is identified, legislators and scientists work together to arrive at a set of policy recommendations. Oftentimes they use statistical analyses to gauge uncertainty— that is, how sure or unsure scientists are about future outcomes—and determine whether the precautionary principle should be employed. As various policy options are vetted, the judiciary weighs in about the constitutionality of the options.

precautionary principle

Acting in a way that leaves a safety margin when the data is uncertain or severe consequences are possible.

477

But policy is determined by much more than science. Political lobbying also plays a large role. In the United States and even on the international stage, political lobbying—contacting elected officials in support of a particular position—is part of the democratic process. (We have access to our elected officials and can share our opinions with them.) Citizens and private organizations (e.g., nonprofits, labor unions, and industry groups) lobby for or against specific proposals, based on their own interests—which can range from the health of the environment to the health of the economy (or their own bottom line) to the future of the planet. Critics say that professional lobbying has grown alarmingly sophisticated and well financed, making individual voices harder to hear and potentially interfering with policy makers’ judgment. Not only do industries run ad campaigns promulgating ideas that serve their own best interests (“clean” coal, for example, is not as clean as it sounds; it still creates heavy pollution and environmental damage), they also contribute large sums of money to candidates for elected office, hoping to influence those candidates, if elected, to act in ways favorable to the industry.

political lobbying

Contacting elected officials in support of a particular position; some professional lobbyists are highly organized, with substantial financial backing.

KEY CONCEPT 24.4

Policy decision making should be influenced by sound science, but political lobbies, public opinion, and the press also strongly influence the process.

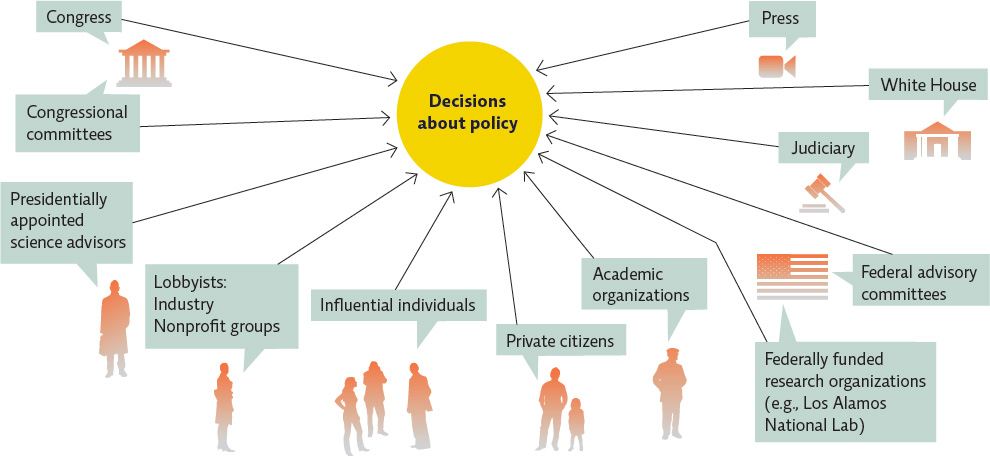

Nonprofits like the National Resources Defense Council (NRDC) also have professional lobbying divisions and do the same thing—spend money to promote their positions to elected officials and to the general public. Taken together, these environmental nonprofit organizations spend millions of dollars per year in federal lobbying efforts; they spent a record $24.6 million in 2009 in the United States, according to the Center for Responsive Politics. Despite this, the deep pockets of industry often outspend these groups—in that same year, the oil and gas industry alone spent an industry-record $175 million for lobbying; the industry total was more than $400 million that year—often supporting provisions that oppose restrictions or regulation, steps that can potentially lead to increased environmental damage.INFOGRAPHIC 24.3

IINFLUENCES ON U.S. ENVIRONMENTAL POLICY DECISION MAKING

Many organizations and individuals influence not only whether we institute a policy to deal with an environmental issue but also the design of that policy—what it covers and how it will be implemented and enforced. The wide variety of voices, many representing differing viewpoints, can make it difficult to create new policies. Though political ideologies might influence how one goes about addressing a problem, policy makers ideally look to the best available science when making decisions about whether a policy is needed to protect the health and well-being of the public and environment.

Based on how you see the process playing out in the United States today, rank the parties that influence U.S. policy making from most influential to least influential. In your opinion, is this ranking as it should be?

Answers will vary but should be supported.

478

479