Forests face a number of threats.

Today global deforestation has slowed, from 8.3 million hectares (ha) per year (20 million acres [ac]) in the 1990s to 5.2 million ha (13 million ac) each year between 2000 and 2010. However, the planet still has a net loss of forested land every year, and the rate of deforestation is actually increasing in some tropical areas, such as Indonesia and Malaysia. (See Chapter 12 for more on deforestation for oil palm plantations in these regions.) There are three main culprits behind this trend of increased deforestation of tropical forests: the harvesting of forests for wood and wood products, the conversion of forests into agricultural land, and urbanization.

hectare (ha)

A metric unit of measure for area; 1 ha = 2.5 acres (ac).

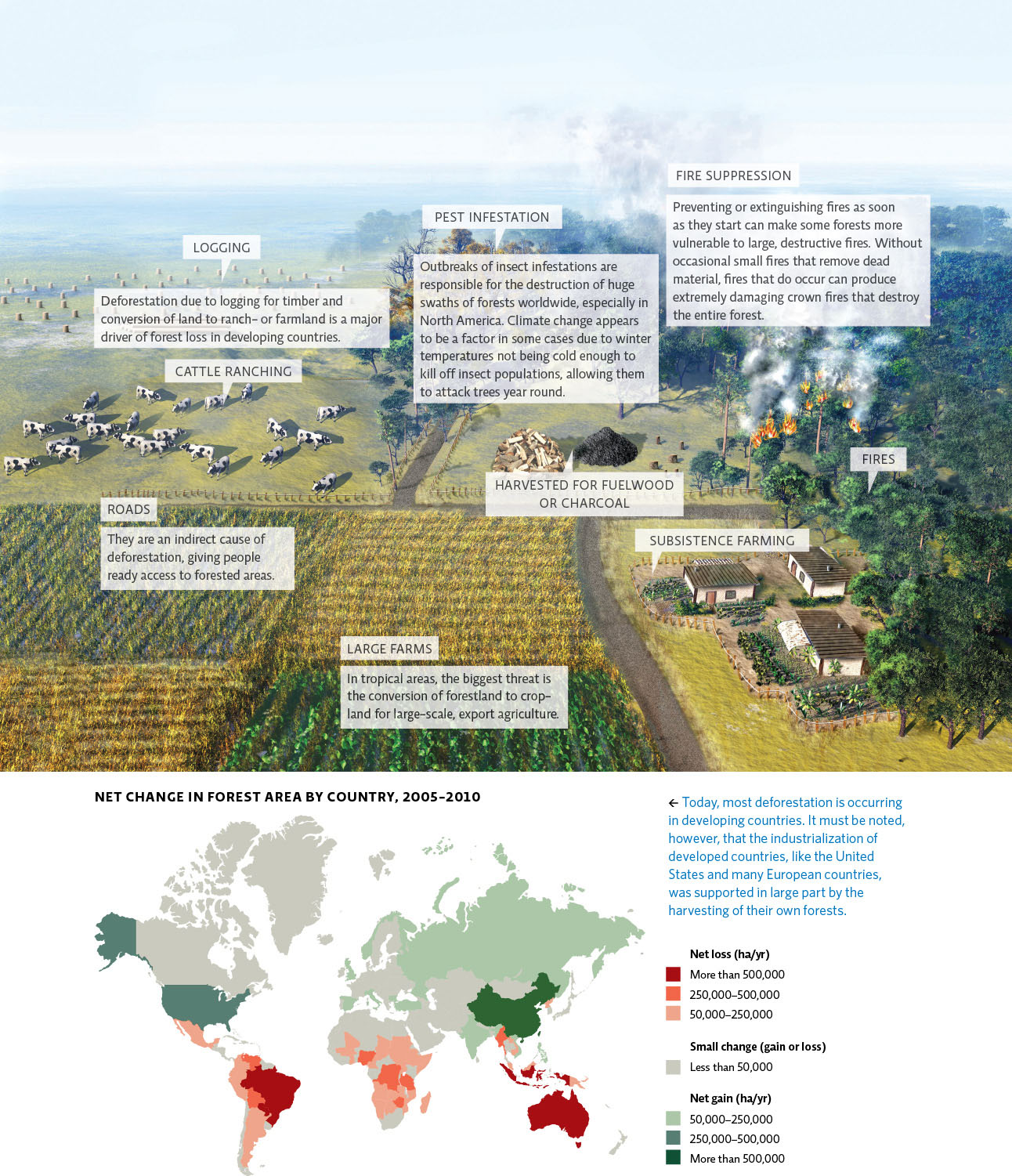

Management of fire is also a factor in forest destruction, especially temperate forests. Frequent fires remove deadwood and other flammable material, but if we suppress these fires, the deadwood builds up so that when a fire does come through, it can burn so hot it catches the entire forest on fire. It turns out that fire is actually needed to maintain some forests whose trees are fire-adapted with seeds that germinate only when exposed to the heat of a fire. In addition, warmer winters allow pest populations that would normally die back during cold months to attack trees year round, taking a toll on temperate and boreal forests. The nature and degree of each of these threats varies by country because forests are often used and managed differently in developing countries than they are in developed ones.

28-13

“The floods got worse, and we lost drinking water to runoff and pollution. And once those problems started, there was no easy way to fix them.”—Timote Georges

In general, deforestation occurs at an increased rate in developing countries like Haiti, where dire poverty and a lack of alternatives force people to harvest their forests or remove them for other land uses. They need wood and charcoal for fuel and housing; they need more space for agriculture; and they need commodities to sell in the marketplace. In most cases, developing countries also have far greater remaining forest stands than developed countries, but many of these stands are falling fast.

KEY CONCEPT 28.4

Globally, forest cover is shrinking due largely to harvesting for lumber and fuel, clearing for agriculture, pest infestations, and fire suppression.

In fact, many if not most developed countries, including the United States, Canada, and most European countries, became developed in part by harvesting their own forests. Today, European countries have fewer forest stands than many developing countries, but they also have much more stringent regulations in place to protect those that are left. These regulations—and the ability to enforce them—help keep deforestation in check.

Of course, any gains made by developed countries are still largely offset by deforestation in countries like Haiti. For example, deforestation in Mexico has largely offset new plantings and reforestation in the United States. Central America has lost more than 5 million ha (12 million ac) since 1990, and Europe has gained 12 million ha (30 million ac). “Industrial countries may be leading the way in conserving their own forests,” says Morton. “But their demand for wood drives much of the deforestation elsewhere.” Multinational corporations have simply moved deforestation operations to developing nations, where regulation and enforcement are often lacking and people are desperate for income. They then export products to wealthier countries for sale. INFOGRAPHIC 28.5

THREATS TO FORESTS

A variety of “drivers” are responsible for deforestation around the world.

How does the presence of roads lead to loss of forests?

Building a road into a forested area that had no roads allows direct access to the area for timber harvesting or for conversion of the land to other uses such as agriculture.